Artificial Intelligence has made massive strides in medical imaging, particularly in segmentation—the process of identifying and outlining boundaries of tumors or organs in scans. However, a persistent shadow hangs over these advancements: bias.

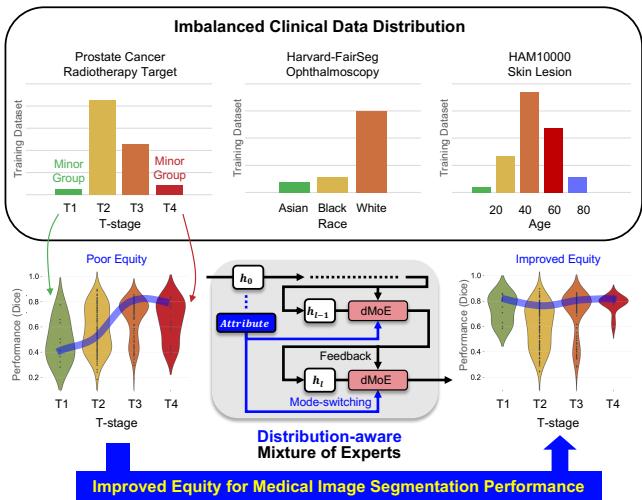

Deep learning models are data-hungry. In clinical practice, data is rarely balanced. We often have an abundance of data from specific demographics (e.g., White patients) or common disease stages (e.g., T2 tumors), but a scarcity of data from minority groups or varying disease severities. When a standard neural network trains on this skewed data, it becomes a “lazy learner.” It optimizes for the majority and fails to generalize to the underrepresented groups. In a medical context, this isn’t just an accuracy problem; it’s an ethical crisis. A model that works perfectly for one patient group but fails for another is unsafe for deployment.

In this post, we are diving into a fascinating research paper, “Distribution-aware Fairness Learning in Medical Image Segmentation From An Control-Theoretic Perspective.” The authors propose a novel framework called Distribution-aware Mixture of Experts (dMoE). What makes this paper unique is that it doesn’t just tweak the data; it reimagines the neural network as a dynamic control system, borrowing heavy-duty concepts from optimal control theory to engineer a fairer model.

The Problem: When “Average” Good Performance Isn’t Good Enough

In medical image segmentation, we usually look at metrics like the Dice score (overlap between the prediction and the ground truth). A model might boast a 90% average Dice score, which sounds fantastic. But if you peel back the layers, you might find it achieves 95% on the majority group and only 60% on a minority group.

The authors identify two main types of attributes that cause this imbalance:

- Demographic Attributes: Race, sex, and age.

- Clinical Factors: Disease severity (e.g., Tumor staging), which impacts the visual appearance of the anatomy.

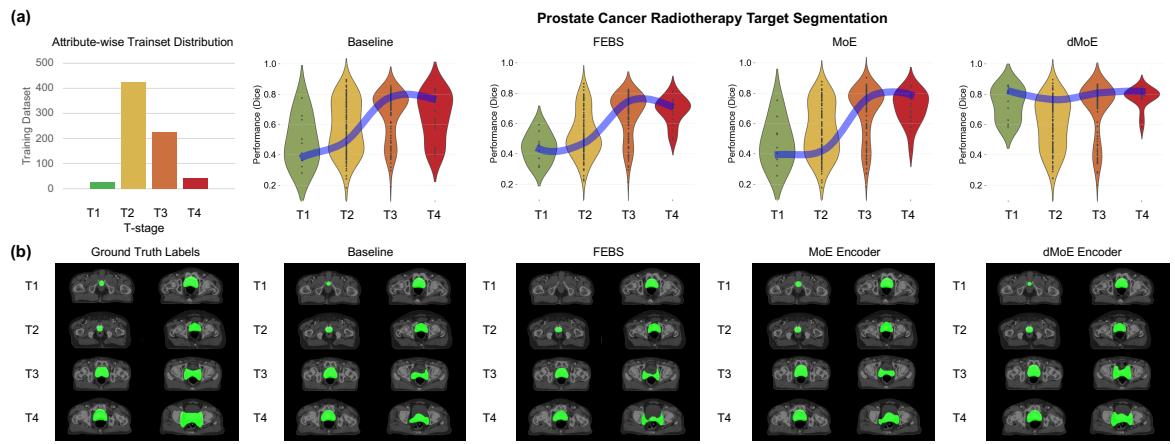

As shown in Figure 1 above, the top section highlights the stark imbalances in standard datasets. For example, the prostate cancer dataset is dominated by T2 and T3 stages, while T1 and T4 are rare. The middle section visualizes the goal: shifting from “Poor Equity” (where performance varies wildly) to “Improved Equity” (where the model performs consistently across all groups).

The Solution: Distribution-aware Mixture of Experts (dMoE)

To solve this, the researchers turned to the Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture but added a critical twist: Distribution Awareness.

What is a Mixture of Experts?

In a standard deep learning layer, every input image is processed by the exact same neurons. A Mixture of Experts (MoE) layer is different. It consists of a set of different neural networks (called “experts”) and a “gating network” (or router). For any given input, the router decides which experts are best suited to handle it.

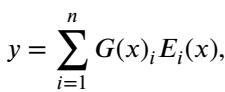

The output of a standard MoE layer is a weighted sum of the chosen experts:

Here, \(G(x)\) is the gating decision and \(E_i(x)\) is the output of the \(i\)-th expert. This allows the model to specialize parts of its network for different types of data.

The “Distribution-aware” Twist

The standard MoE routes based solely on the input image features (\(x\)). The authors argue that to achieve fairness, the router needs to explicitly know the attribute (e.g., “This patient is Stage T4” or “This patient is from the minority demographic”).

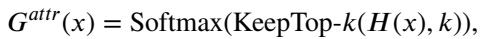

They propose dMoE, where the gating network \(G\) is conditioned on the attribute flag (\(attr\)). The new formulation looks like this:

In this equation:

- \(\tilde{h}_l\) is the image feature input.

- \(G^{attr}\) is the attribute-specific router.

- The router selects the top-\(k\) experts (usually 2 out of 8) to process the feature.

This allows the network to dynamically switch “modes” based on who the patient is or how severe their disease is.

The Architecture

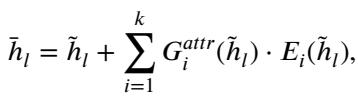

This dMoE module isn’t a standalone model; it is a building block that can be inserted into existing powerful architectures like Transformers (TransUNet) or CNNs (3D ResUNet).

As seen in Figure 2(a), the attribute flag flows directly into the router networks. The router computes scores for all experts and applies a Noisy Top-K Gating mechanism to keep only the most relevant ones active. The gating function is defined as:

This ensures that the model focuses its computational power on the experts that have learned to handle that specific distribution of data.

The Theory: Neural Networks as Control Systems

One of the most intellectually satisfying parts of this paper is how it frames the fairness problem using Optimal Control Theory. If you aren’t an engineer, this might sound intimidating, but the analogy is quite intuitive.

1. Neural Networks are Dynamical Systems

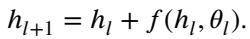

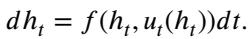

We can view the layers of a neural network as time steps in a dynamical system. The “state” of the system is the feature map \(h\), which evolves as it passes through layers (time). A standard residual block update looks like this:

This looks remarkably like the Euler method for solving Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs). In continuous time, this is:

Here, \(u_t\) represents the “control” (the weights/parameters) applied at time \(t\).

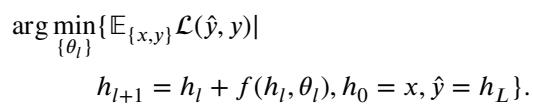

2. Training is Optimal Control

Training a neural network is essentially trying to find the best sequence of controls (weights) to minimize the error (loss function) at the end of the process.

3. From Open-Loop to Feedback Control

Standard neural networks are Non-feedback (Open-loop) systems (see Figure 2b, left). The weights are fixed after training. The network applies the same transformation regardless of the intermediate state.

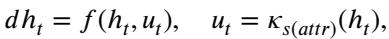

The Mixture of Experts (MoE) changes this. Because the router looks at the current input \(h_t\) to decide which expert to use, the control \(u_t\) becomes a function of the state. This is Feedback (Closed-loop) Control:

This makes the system adaptive. It can adjust its trajectory based on where it currently is in the feature space.

4. dMoE is Mode-Switching Control

The authors take it one step further. In complex mechanical systems (like flight control), a single feedback law isn’t enough. You need different “modes” for takeoff, cruising, and landing.

The dMoE acts as a Mode-Switching Controller. It switches its control strategy based on external environmental variables—in this case, the demographic or clinical attributes (\(attr\)).

Here, \(s(attr)\) determines which policy \(\kappa\) to use. By mathematically proving that the MoE structure approximates this kernel-based control function, the authors provide a rigorous theoretical justification for why dMoE works better for fairness: it literally changes its “operating mode” to suit the sub-population it is looking at.

Experimental Results

Theory is great, but does it work on actual medical scans? The researchers tested dMoE on three datasets:

- Harvard-FairSeg (2D): Eye fundus images (Race attribute).

- HAM10000 (2D): Skin lesion dermatology images (Age attribute).

- Prostate Cancer (3D): CT scans for radiotherapy (Tumor Stage attribute).

They compared dMoE against state-of-the-art fairness methods, including FEBS (Fair Error-Bound Scaling) and standard MoE.

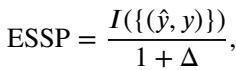

To measure success, they used standard segmentation metrics (Dice Score, IoU) and a fairness-adjusted metric called Equity-Scaled Segmentation Performance (ESSP):

This metric penalizes the score if there is a high variance (\(\Delta\)) in performance between different subgroups.

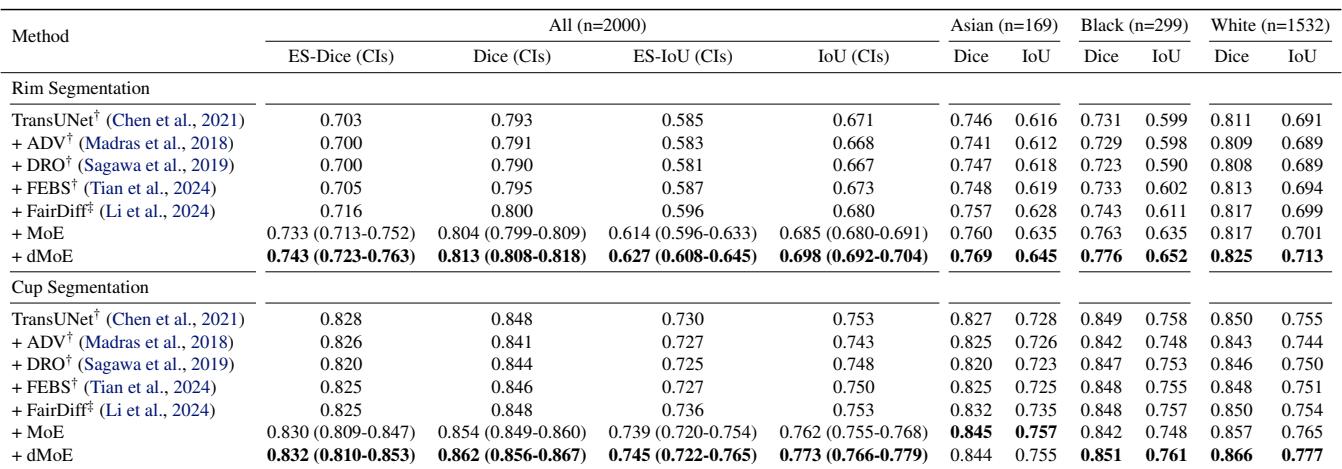

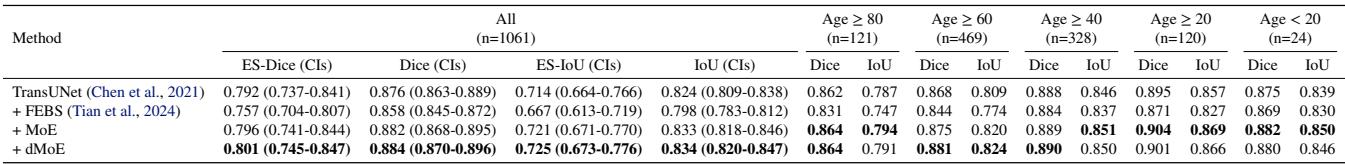

Result 1: Addressing Racial Bias in Eye Scans

In the Harvard-FairSeg dataset, the “Black” and “Asian” subgroups are often underrepresented or harder to segment.

Looking at Table 1, standard methods (TransUNet) struggle with the Black subgroup (Dice 0.731). The dMoE approach pushes this to 0.776, a significant leap. It also achieves the highest Equity-Scaled (ES) scores, meaning it improved the minority without sacrificing the performance on the majority (White) group.

Result 2: Addressing Age Bias in Dermatology

For skin lesions, age groups are highly imbalanced.

In Table 2, we see dMoE achieving the highest ES-Dice (0.801) and ES-IoU. It consistently outperforms FEBS, which actually dropped performance in some cases compared to the baseline.

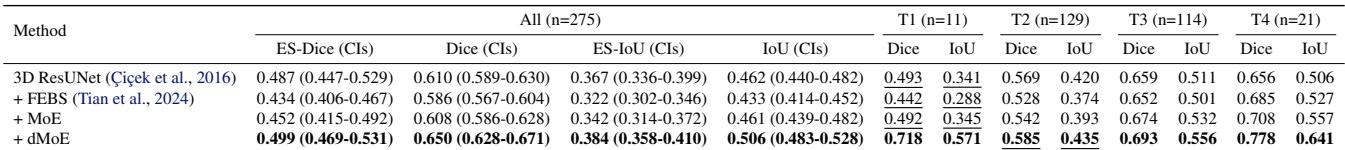

Result 3: Clinical Fairness in 3D Cancer Treatment

This is perhaps the most critical experiment. In prostate cancer, T4 (advanced) tumors are rare but critical to segment correctly for radiation therapy.

Table 3 shows massive improvements. For the T4 subgroup, the baseline model scored 0.656. The dMoE model scored 0.778. That is a game-changing improvement for treatment planning in advanced cancer cases.

We can visualize this improvement clearly in Figure 3:

In the violin plots (a), notice how the dMoE (far right) keeps the blue “equity line” straight and high across all stages (T1 to T4). The Baseline and FEBS models dip significantly at the edges (T1 and T4). The qualitative images (b) confirm this: look at the T4 row. The dMoE segmentation (green overlay) is much closer to the Ground Truth than the other methods.

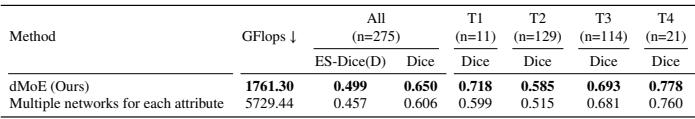

Efficiency Analysis

One might ask: “Why not just train separate models for each group?” The authors compared dMoE against training multiple separate networks.

As shown in Table 8, dMoE is not only more accurate (ES-Dice 0.499 vs 0.457), but it is also drastically more efficient (1761 GFlops vs 5729 GFlops). By sharing knowledge in the “experts” while routing via the “gating network,” dMoE gets the best of both worlds: specialization and shared learning.

Conclusion & Implications

The Distribution-aware Mixture of Experts (dMoE) represents a significant step forward in ethical AI for healthcare. By stepping back and viewing the neural network through the lens of Control Theory, the authors identified that addressing fairness isn’t just about feeding the model more data—it’s about giving the model the mechanisms to adapt its strategy based on the context (demographics or disease state).

Key Takeaways:

- Context Matters: Feeding the attribute (race, age, stage) into the model’s routing layer allows for dynamic adaptation.

- Theory Drives Practice: The mode-switching control interpretation explains why MoE structures are effective for heterogeneous data.

- No Compromise: dMoE improves performance on minority groups without degrading the majority, solving the “equity-accuracy trade-off.”

While the study focused on single attributes, the future lies in handling intersectional biases (e.g., Age and Race combined). As AI continues to integrate into clinical workflows, frameworks like dMoE will be essential to ensure that these powerful tools serve every patient equitably, not just the “average” one.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.00619/images/cover.png)