In the world of machine learning, predictions are rarely the end goal. We predict to act. A doctor predicts a diagnosis to choose a treatment; a self-driving car predicts pedestrian movement to steer; a financial algorithm predicts market trends to trade.

In low-stakes environments, like recommending a movie, it is acceptable to maximize the expected utility. If the model is wrong, the user wastes two hours on a bad movie—unfortunate, but not catastrophic. However, in high-stakes domains like medicine or robotics, the cost of error is asymmetric. Relying solely on the “most likely” outcome can be dangerous. If a model is 90% sure a tumor is benign, acting on that probability might maximize expected utility, but it ignores the catastrophic risk of the 10% chance that it is malignant.

This brings us to a fundamental problem: How do we interface uncertain predictions with decision-making when we are risk-averse?

In a recent paper, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania propose a rigorous framework that connects uncertainty quantification with decision theory. They introduce Risk-Averse Calibration (RAC), a method that proves prediction sets (sets of potential labels rather than single points) are mathematically optimal for risk-averse agents.

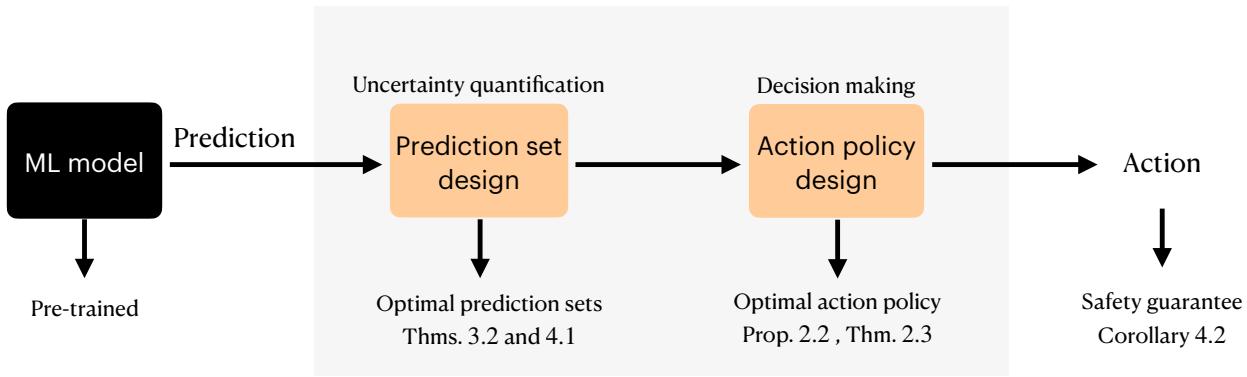

As shown in Figure 1, the goal is to move from a raw ML model to an optimal action policy that provides a safety guarantee. This post will break down the decision-theoretic foundations of this work, explain why prediction sets are the correct language for risk aversion, and detail the RAC algorithm.

The Problem: Risk Neutrality vs. Risk Aversion

To understand the contribution of this paper, we first need to define the setting. We have:

- Features (\(X\)): The input data (e.g., a chest X-ray).

- Labels (\(Y\)): The true outcome (e.g., “Pneumonia”).

- Actions (\(A\)): The choices available to the decision maker (e.g., “Prescribe Antibiotics”, “Send home”, “Further testing”).

- Utility (\(u(a, y)\)): A function that scores how good action \(a\) is if the true label is \(y\).

The Risk-Neutral Agent

Standard machine learning approaches usually assume the agent is risk-neutral. They rely on calibration, where the model outputs a probability vector \(\hat{p}\). If a model is perfectly calibrated, the optimal strategy is to pick the action that maximizes expected utility:

\[ a^* = \text{argmax}_{a \in A} \mathbb{E}_{y \sim \hat{p}}[u(a, y)] \]This works well on average. However, “on average” isn’t good enough when the “worst case” is unacceptable.

The Risk-Averse Agent

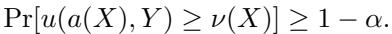

A risk-averse agent doesn’t care just about the average; they care about the Value at Risk (VaR). They want a guarantee. Specifically, they want to find a utility certificate \(\nu(X)\)—a guaranteed minimum utility value—such that:

In simpler terms: “With probability \(1 - \alpha\) (e.g., 95%), I guarantee that the utility of my action will be at least \(\nu(X)\).”

The objective of the paper is to find an action policy \(a(X)\) and a certificate \(\nu(X)\) that maximizes this guaranteed utility, subject to the safety constraint.

Why Prediction Sets are the Answer

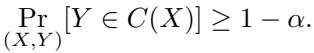

Historically, uncertainty quantification often relies on Conformal Prediction (CP), which produces prediction sets \(C(X)\). These are subsets of labels guaranteed to contain the true label with high probability:

A major theoretical contribution of this paper is answering the question: Why should we use prediction sets?

The authors prove that for a risk-averse decision maker, prediction sets are a sufficient statistic. This means that optimizing for the risk-averse objective is mathematically equivalent to designing an optimal prediction set and then applying a specific decision rule to it.

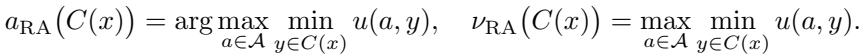

The Max-Min Decision Rule

If you are given a prediction set \(C(X)\) that you know contains the true label (with high probability), how should you act?

If you are risk-averse, you assume the environment is adversarial. You look at all the possible labels inside the set \(C(X)\), imagine the worst one (the one that hurts your utility the most for a given action), and then choose the action that gives the best outcome in that worst-case scenario.

This is formally known as the Max-Min Decision Rule:

The authors prove that this simple rule is minimax optimal. If all you know is that the true label is inside \(C(X)\), this strategy protects you against the worst-case distribution of data consistent with that knowledge.

The Equivalence Theorem

The most striking theoretical result in the paper is the equivalence between the general decision-making problem (RA-DPO) and the problem of optimizing prediction sets (RA-CPO).

The authors show that you do not need to solve a complex optimization over all possible policies. Instead, you can focus entirely on designing the “best” prediction set—where “best” means the set that maximizes the max-min utility—and then simply apply the max-min rule. If you construct the optimal prediction set, you automatically derive the optimal risk-averse policy.

Designing the Optimal Prediction Set

We have established that we need prediction sets, and we know how to act once we have them. But not all prediction sets are created equal. We could satisfy the coverage guarantee by simply returning the set of all labels every time (e.g., “The diagnosis is either Healthy, Pneumonia, or COVID”). This is safe, but useless—it has zero utility.

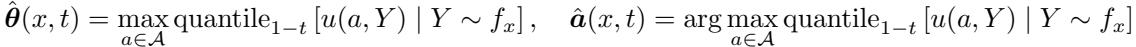

We need to make the sets as small and informative as possible to maximize utility. The paper formulates this as Risk Averse Conformal Prediction Optimization (RA-CPO):

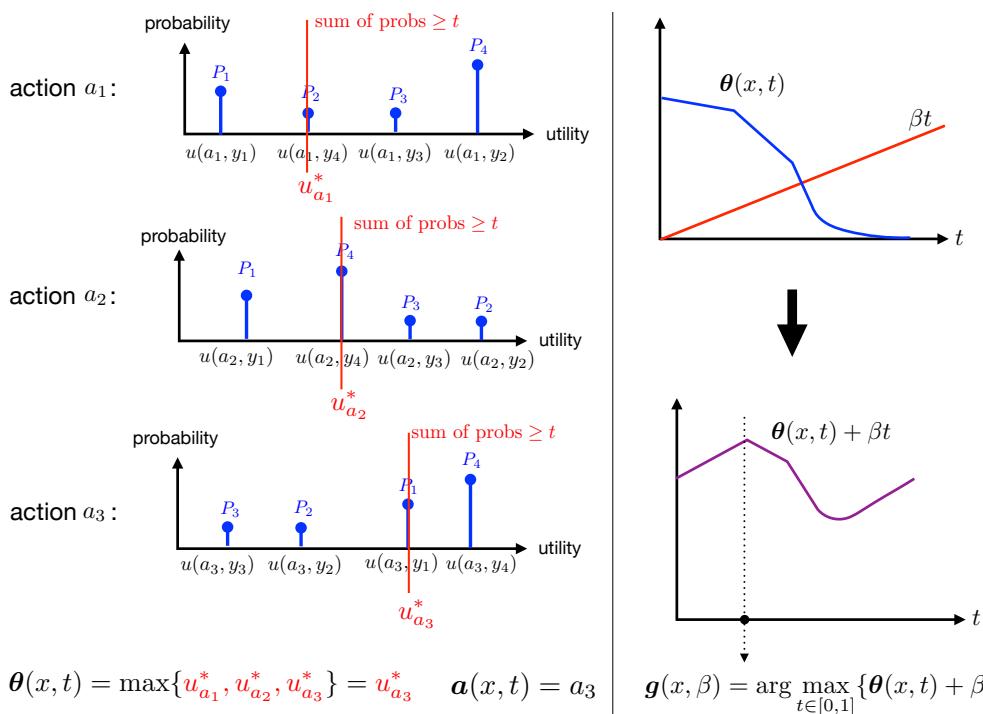

To solve this, the authors introduce a novel re-parameterization of the problem involving two key functions, \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and \(\boldsymbol{g}\).

Understanding \(\theta(x, t)\)

The function \(\theta(x, t)\) represents the maximum risk-averse utility achievable for a specific input \(x\) if we are allocated a “coverage budget” of \(t\).

Imagine you are forced to cover the true label with probability \(t\). You would pick the set of labels that are most likely, summing up to probability \(t\). Then, you would pick the action that maximizes the minimum utility over that set. \(\theta(x, t)\) is the resulting utility value.

The Structure of the Optimal Set

Using duality theory, the authors show that the optimal prediction sets have a specific structure controlled by a single scalar parameter, \(\beta\).

As illustrated in Figure 2:

- Left: For a given coverage probability \(t\), we calculate the best worst-case utility \(\theta(x, t)\).

- Right: We need to choose the optimal coverage \(t^*(x)\) for each specific input \(x\). This is determined by maximizing \(\theta(x, t) + \beta t\).

The parameter \(\beta\) acts as a “price” for coverage. It balances the global requirement (covering 95% of cases on average) with the local desire to maximize utility. The optimal coverage assignment \(t^*(x)\) is given by the function \(\boldsymbol{g}(x, \beta)\):

This theoretical characterization is powerful because it reduces the complex problem of set design down to finding a single optimal scalar \(\beta\).

The Algorithm: Risk Averse Calibration (RAC)

The theory assumes we know the true probability distributions. In practice, we only have a finite dataset and a “black box” model (like a neural network) that outputs estimated probabilities \(f_x\).

The authors propose Risk Averse Calibration (RAC), a finite-sample algorithm that bridges the gap between theory and practice. RAC works by treating the pre-trained model as a base and calibrating the parameter \(\beta\) to ensure valid coverage.

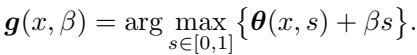

Step 1: Estimating the Functions

First, RAC uses the model’s output \(f_x\) to compute empirical versions of the utility functions, denoted as \(\hat{\theta}(x, t)\) and \(\hat{a}(x, t)\):

Step 2: Calibrating \(\beta\)

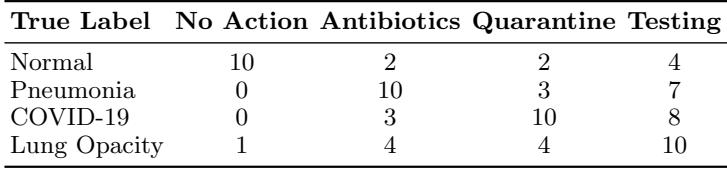

The core of the algorithm is finding the correct \(\beta\). We want the smallest \(\beta\) (which encourages smaller, more useful sets) that still satisfies the safety constraint.

For a test point \(x_{\text{test}}\), the algorithm computes a specific \(\beta\) for every possible candidate label \(y\), effectively checking: “If \(y\) were the true label, what \(\beta\) would I need to make sure my set is valid?”

Step 3: Constructing the Set

Finally, the prediction set \(C_{\text{RAC}}\) includes every label \(y\) that is “plausible” given the calibrated \(\beta\):

The authors prove a crucial theorem: RAC satisfies distribution-free marginal coverage.

\[ \Pr[Y_{\text{test}} \in C_{\text{RAC}}(X_{\text{test}})] \ge 1 - \alpha \]This means that regardless of the true underlying data distribution, the sets produced by RAC will contain the true label with the desired probability (e.g., 95%). Consequently, the resulting decision policy satisfies the safety guarantee on utility.

Experiments: Medicine and Movies

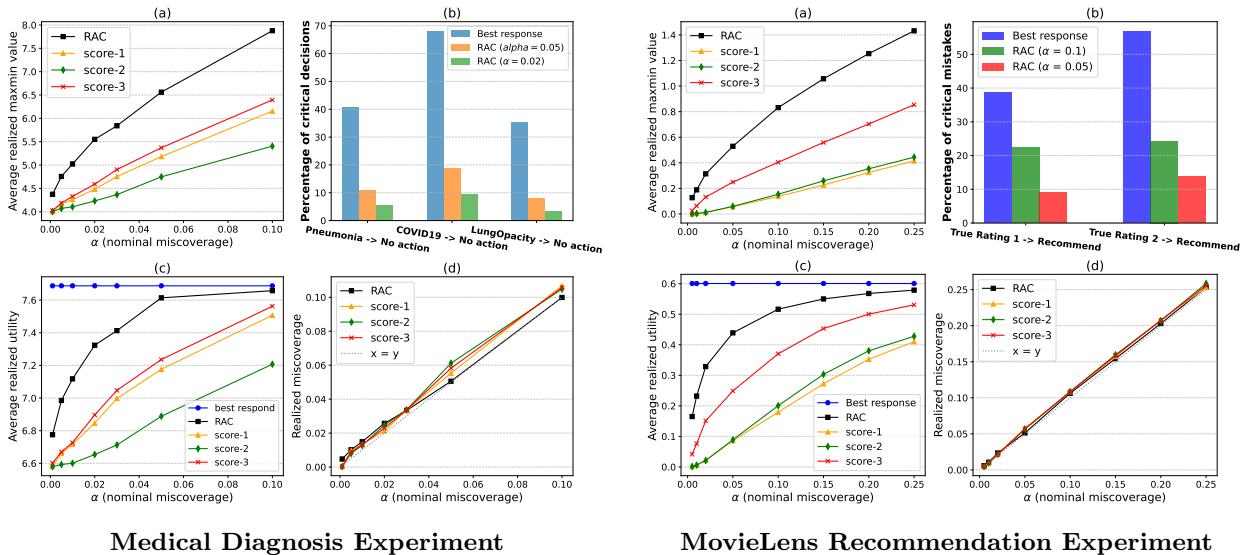

To demonstrate the effectiveness of RAC, the authors tested it in two contrasting domains: medical diagnosis (high stakes) and movie recommendations (lower stakes but clear utility trade-offs).

Medical Diagnosis (Chest X-Ray)

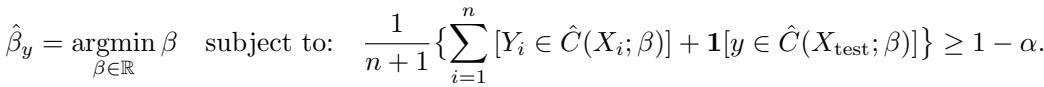

They used the COVID-19 Radiography Database, classifying images into four categories: Normal, Pneumonia, COVID-19, and Lung Opacity.

They defined a specific utility matrix to reflect clinical realities. For example, failing to treat Pneumonia (No Action) has a utility of 0 (very bad), while giving antibiotics to a healthy person has a utility of 2 (bad, but better than death).

Results

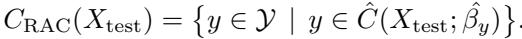

The authors compared RAC against several baselines:

- Best Response: A standard approach that trusts the model’s probabilities and maximizes expected utility.

- Conformal Prediction + Max-Min: Using standard conformal scores (like “Score-1” or “Score-2”) to build sets, then applying the max-min rule.

The results highlight the strength of RAC:

Key Takeaways from Figure 3:

- Graph (a): RAC (black squares) consistently achieves a higher “utility certificate” (max-min value) than other conformal methods across different risk levels (\(\alpha\)). This means it gives stronger guarantees.

- Graph (b) - Critical Mistakes: This is the most important chart for safety. The “Best Response” method (blue bars)—which ignores prediction sets—makes a massive number of critical mistakes. In the COVID-19 case, it recommends “No Action” over 60% of the time because it chases expected utility. RAC (orange/green bars) drives this error rate down dramatically (below 10%).

- Graph (c): While the Best Response method technically has high average utility, RAC outperforms the other safe (prediction-set based) methods. It finds the “sweet spot” of being safe without being overly conservative.

The experiments confirm that simply “trusting the model” (Best Response) is dangerous in high-stakes settings. Standard Conformal Prediction is safe, but can be inefficient. RAC optimizes the set structure specifically for the downstream decision, providing the best of both worlds: rigorous safety and high utility.

Conclusion and Implications

This paper establishes a foundational link between conformal prediction and decision theory. It proves that prediction sets are not just a heuristic for uncertainty; they are the optimal sufficient statistic for risk-averse decision making.

By using Risk-Averse Calibration (RAC), practitioners in safety-critical fields like healthcare or autonomous driving can:

- Take any black-box model.

- Wrap it with a rigorous safety layer.

- Generate optimal action policies that maximize utility while guaranteeing that catastrophic risks are kept below a user-defined threshold.

While the current work focuses on marginal guarantees (averages over the population), the framework lays the groundwork for future extensions into group-conditional or label-conditional safety, pushing us closer to AI systems we can trust when the stakes are highest.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.02561/images/cover.png)