Introduction

If you have ever worked with Transformers—the architecture behind the current AI revolution—you know they have a peculiar quirk: they are set functions. If you feed a Transformer the sentence “The cat sat on the mat” or “mat on sat cat The,” the core attention mechanism treats them almost identically. It has no inherent concept of order or space.

To fix this, we use Position Encodings (PEs). For Large Language Models (LLMs), the industry standard has become RoPE (Rotary Position Embeddings). RoPE is fantastic for 1D text sequences. However, as we push Transformers into the world of robotics and computer vision, we aren’t just dealing with a sequence of words anymore. We are dealing with 2D images, 3D point clouds, and robot limbs moving through physical space.

How do we represent position in these higher dimensions? Simply hacking 1D RoPE into 3D often yields suboptimal results.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into a new paper titled “Learning the RoPEs: Better 2D and 3D Position Encodings with STRING.” The researchers introduce STRING, a unifying theoretical framework that not only generalizes RoPE but improves upon it significantly for vision and robotics tasks.

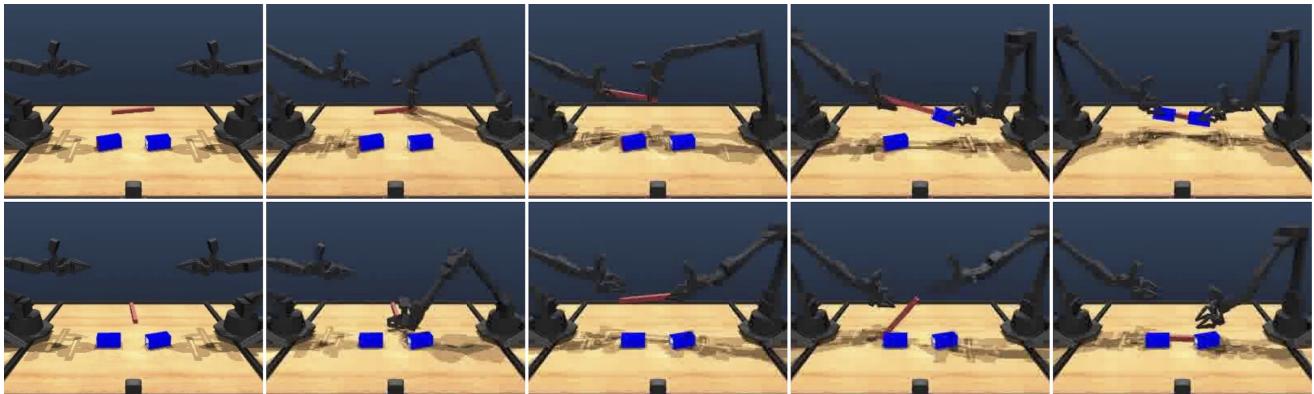

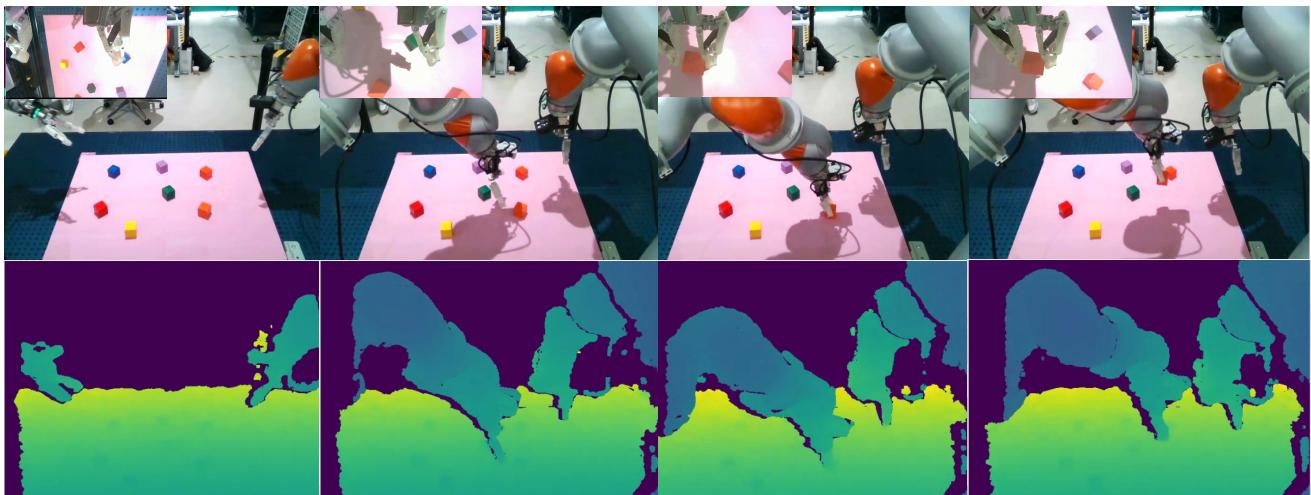

As shown in Figure 1 above, the difference isn’t just academic. In complex robotic manipulation tasks, using STRING can be the difference between a robot successfully stacking a block and flailing helplessly.

The Background: Why Position Matters

Before understanding STRING, we need to understand the landscape it enters.

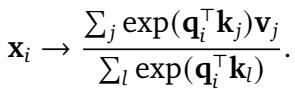

In the standard Transformer attention mechanism (Equation 1 below), the similarity between a Query (\(\mathbf{q}\)) and a Key (\(\mathbf{k}\)) is calculated using a dot product.

The problem is that \(\mathbf{q}_i^\top \mathbf{k}_j\) yields the same scalar result regardless of where \(i\) and \(j\) are located in the sequence.

The Rise of RoPE

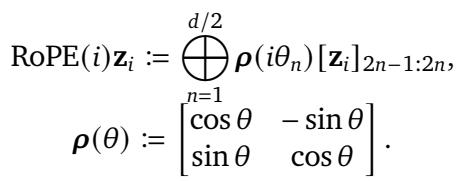

To solve this, researchers developed Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE). Instead of adding a position vector to the input (like in the original “Attention Is All You Need” paper), RoPE rotates the query and key vectors based on their position.

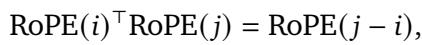

Mathematically, RoPE multiplies the vector by a block-diagonal matrix of rotation matrices. The “magic” of RoPE is Translational Invariance. The attention score between two tokens depends only on the relative distance between them (\(j - i\)), not their absolute positions.

This property is crucial for generalization. If a model learns to recognize the phrase “deep learning” at the start of a sentence, translational invariance ensures it recognizes it at the end of a sentence too.

The Problem with Higher Dimensions

When researchers apply RoPE to 2D images or 3D data, they typically use a “factorized” approach. They treat the x, y, and z coordinates independently and apply 1D RoPE to each, effectively stacking them.

While this works reasonably well, it is somewhat ad-hoc. It assumes that the interaction between spatial dimensions can be modeled simply by independent rotations. The authors of STRING argue that there is a much more general, mathematically rigorous way to handle position that naturally extends to any dimension.

The Core Method: Introducing STRING

STRING stands for Separable Translationally Invariant Generalized Position Encodings.

The core insight of the paper is rooted in Lie Group theory. The researchers realized that RoPE is just one specific instance of a much broader class of transformations. They asked: What is the most general way to transform queries and keys such that their dot product remains translationally invariant?

The Universal Formula

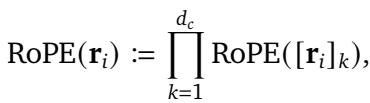

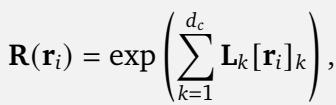

The authors define STRING using the matrix exponential. Instead of fixed rotation matrices, STRING uses a set of learnable generators (\(\mathbf{L}_k\)).

Here, \(\mathbf{r}_i\) is the position vector (which could be 1D, 2D, or 3D). The position encoding is applied via matrix multiplication:

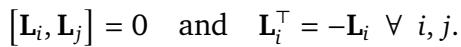

For this to work—specifically, for the encoding to be separable (applied to query and key independently) and translationally invariant—the generators \(\mathbf{L}_k\) must satisfy specific properties. They must be skew-symmetric (meaning \(\mathbf{L}^\top = -\mathbf{L}\)) and they must commute (order of multiplication doesn’t matter).

Why is this cool? The authors prove a powerful theorem: STRING is the most general translationally invariant position encoding algorithm (using matrix multiplication).

This means RoPE is actually just a specific “flavor” of STRING. If you manually select the generators \(\mathbf{L}\) to look like specific block-diagonal matrices, you get RoPE back. But if you learn these generators from data, you can find position encodings that are better suited for specific tasks, like 3D depth perception.

Making It Efficient: Cayley and Circulant STRING

You might be thinking: “Matrix exponentials? That sounds computationally expensive.” You would be right. Computing the exponential of a dense \(d \times d\) matrix for every token is too slow for training large models (\(O(d^3)\) complexity).

To make STRING practical, the authors introduce two efficient variants that maintain the theoretical benefits while keeping the computational footprint low.

1. The “RoPE in a New Basis” Trick

The authors prove that any STRING encoding can be rewritten as RoPE sandwiched between two orthogonal matrices \(\mathbf{P}\).

This implies that we can implement STRING by simply taking standard RoPE and learning a transformation matrix \(\mathbf{P}\) that rotates the data into a better basis before applying the position encoding. This is incredibly efficient because RoPE is sparse (mostly zeros), so it’s fast to compute.

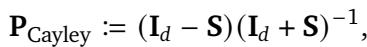

2. Cayley-STRING

One way to parameterize this orthogonal matrix \(\mathbf{P}\) is using the Cayley Transform. It avoids expensive matrix inversions and ensures the matrix remains orthogonal during training.

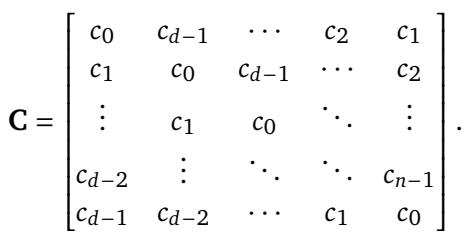

3. Circulant-STRING

Another efficient variant uses Circulant Matrices. A circulant matrix is defined by a single vector, where each row is a rotated version of the previous one.

Because of their structure, operations with circulant matrices can be computed extremely fast (\(O(d \log d)\)) using Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT). This makes Circulant-STRING a great choice when speed is a priority.

Experiments & Results

The researchers didn’t just stop at the math; they put STRING to the test across a wide variety of tasks, ranging from standard image classification to complex robotic manipulation.

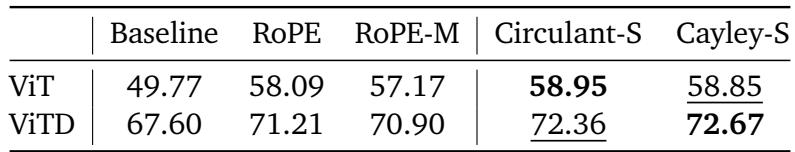

1. General Vision Tasks (2D)

The first test ground was standard computer vision. They tested STRING on ImageNet (classification) and WebLI (image-text retrieval).

In ImageNet classification, STRING variants (Cayley and Circulant) outperformed standard ViT and RoPE. While the margins on ImageNet are often small, STRING provided the first absolute gains larger than 1% compared to regular ViTs in some configurations, with negligible extra parameters.

2. 3D Object Detection

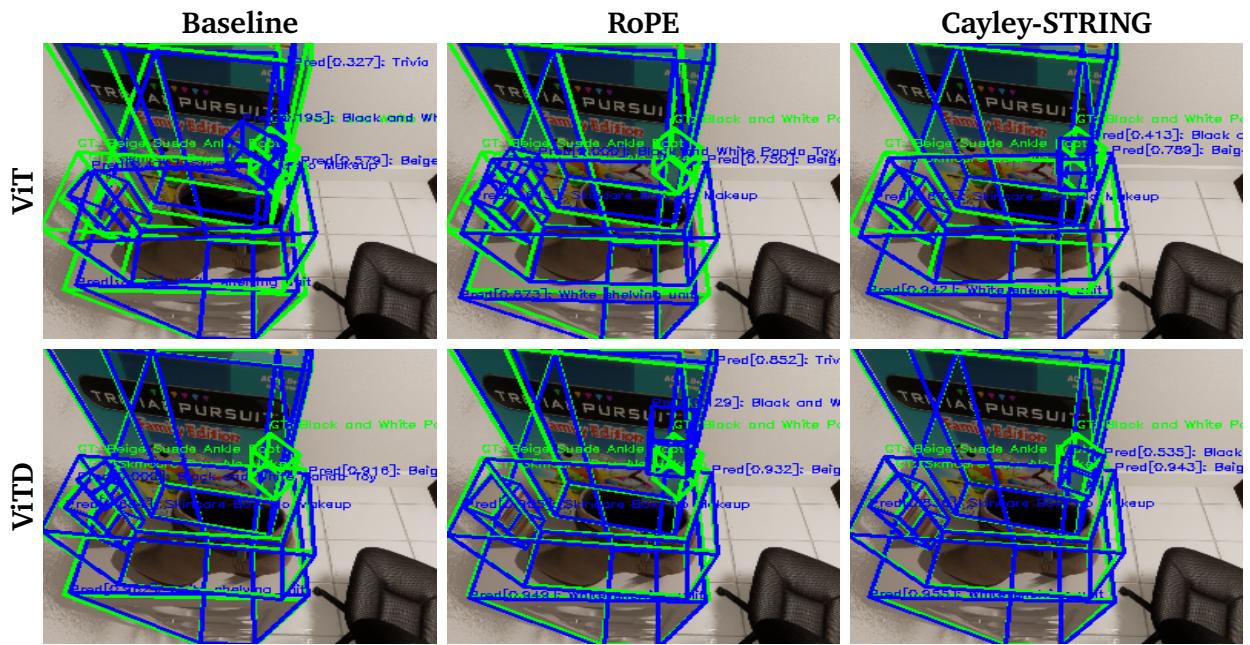

Things get more interesting when we move to 3D. The authors modified the OWL-ViT architecture to predict 3D bounding boxes instead of just 2D ones.

As seen in Figure 2 above, the Cayley-STRING model (right column) produces much tighter and more accurate 3D bounding boxes (blue) compared to the Baseline and RoPE. The confidence scores are also generally more indicative of the object presence.

Quantitatively, STRING models provided substantial improvements. For Vision Transformers with depth input (ViTD), Cayley-STRING provided a 2% relative improvement over the best RoPE variant. This suggests that the learned basis allows the model to better interpret the relationship between 2D pixels and 3D depth.

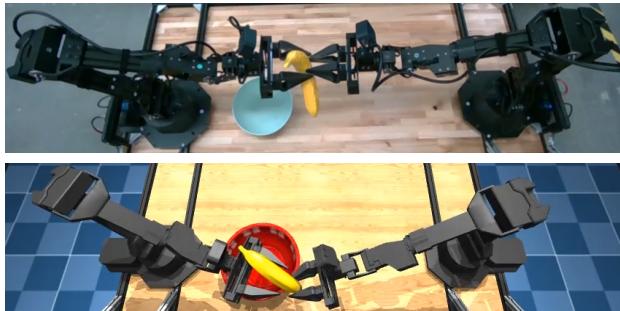

3. Robotics: The Ultimate Test

The most compelling results come from robotic manipulation tasks using the ALOHA simulation and real-world KUKA robots. Robotics requires precise spatial reasoning—knowing exactly where a gripper is relative to a mug is critical.

ALOHA Simulation

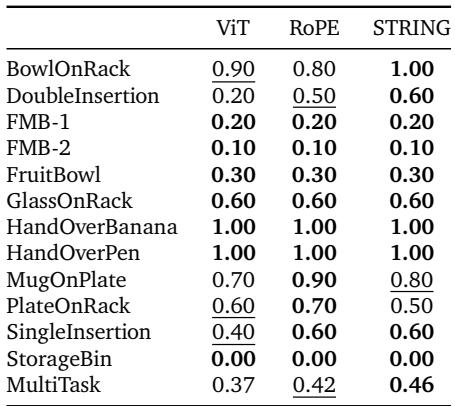

The team tested the models on 12 dexterous tasks, such as “HandOverBanana,” “DoubleInsertion,” and “MugOnPlate.”

They compared a baseline Vision Transformer (ViT), RoPE, and STRING. The results were clear:

STRING (specifically Cayley-STRING) achieved the best success rate across 11 of the 13 tasks. In the “MultiTask” aggregate score, it beat RoPE by a solid margin (0.46 vs 0.42).

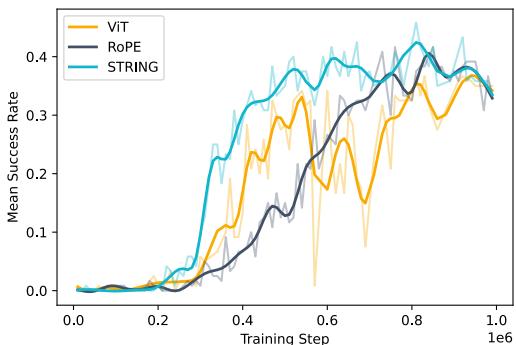

Furthermore, STRING learns faster. Figure 4 below shows the training curves. You can see the light blue line (STRING) consistently staying above the others, converging to a higher success rate earlier in the training process.

Real-World Robustness

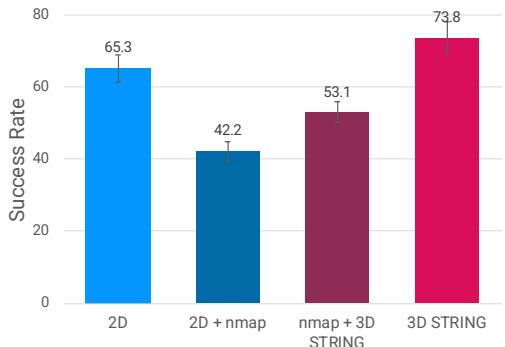

Finally, the team deployed these policies on a real KUKA robot arm. They experimented with different ways of feeding 3D depth data into the model.

A common technique in robotics is to convert depth into “Surface Normal Maps” (nmap) and feed those as images. However, depth sensors are noisy. The researchers found that adding noisy normal maps actually hurt the performance of standard 2D baselines (dropping success from 65% to 42%).

Enter STRING. When they used STRING to encode the 3D position directly (lifting patches to 3D), performance jumped to 74%.

Figure 5 shows this dramatic difference. The ability of STRING to robustly handle 3D coordinates allows the policy to ignore sensor noise that confuses standard convolution-based or nmap-based approaches.

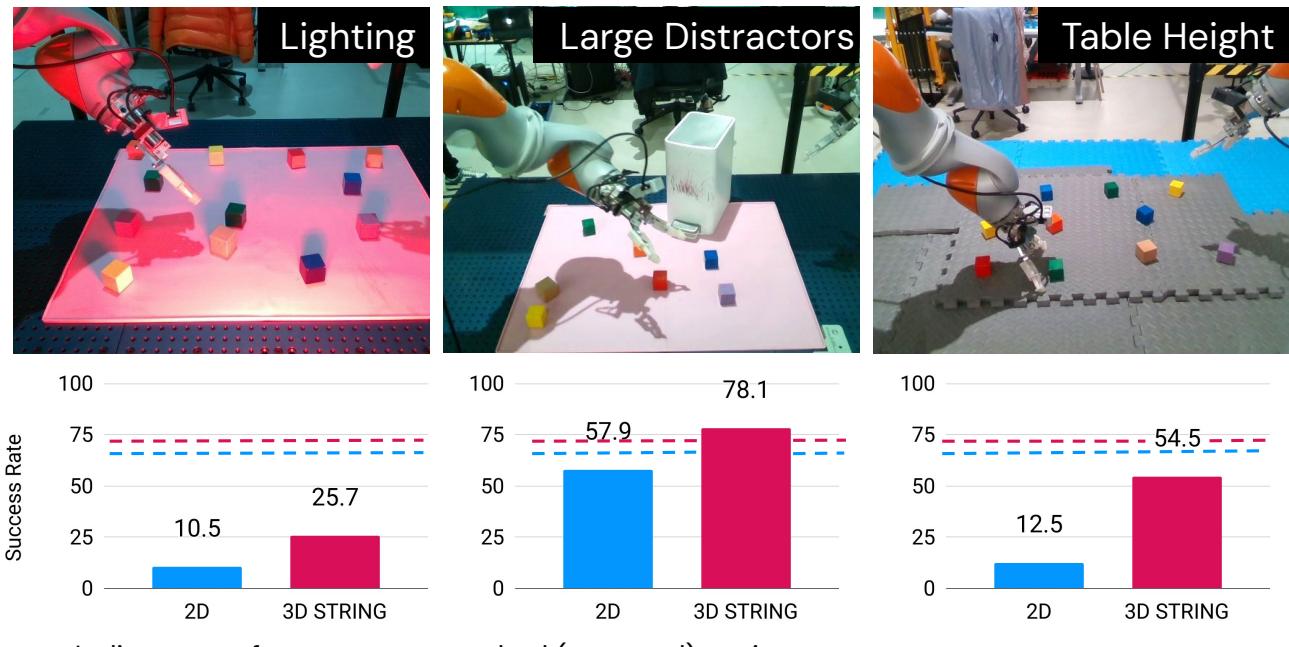

They also tested the robot in Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) scenarios—changing lighting, table height, or adding distractors.

As shown in Figure 6, the 3D STRING policy (magenta line) is significantly more robust than the 2D baseline (blue line). In the “Large Distractors” case (middle), the 2D model’s performance collapses, while STRING maintains high accuracy. The “Table Height” variation is particularly telling—standard cameras can’t easily see that a table is 10cm lower, but a STRING-encoded policy with depth awareness handles it effortlessly.

Figure 7 provides a visualization of what the robot “sees” (RGB and Depth heatmaps) during a successful task. The model effectively focuses on the relevant objects despite the clutter.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Learning the RoPEs” offers a compelling evolution of position encodings. By stepping back and viewing position encoding through the lens of Lie Group theory, the authors derived STRING: a method that is theoretically sound, computationally efficient, and empirically superior.

Key Takeaways:

- RoPE is a subset of STRING: We can do better than fixed rotations by learning the transformation basis.

- 3D matters: While RoPE is great for text, STRING shines in domains with complex spatial geometries like robotics and 3D perception.

- Efficiency is solved: Through Cayley transforms and Circulant matrices, we can get these benefits without slowing down the model.

For students and practitioners in Embodied AI and Computer Vision, this represents a shift away from ad-hoc spatial hacks toward a unified, learnable approach to geometry. As we ask robots to perform increasingly complex tasks in unstructured 3D environments, tools like STRING will likely become standard components in the neural architecture stack.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.02562/images/cover.png)