Introduction

If you have ever trained a deep learning model, you have likely used Adam or AdamW. These adaptive optimizers are the engines of modern AI, powering everything from simple classifiers to massive LLMs. They work by adapting to the geometry of the loss landscape “on-the-fly,” adjusting step sizes based on the gradients they encounter during training.

But here is a provocative question: Why are we treating neural networks as black-box optimization problems?

We know the structure of a Transformer or a ResNet. We designed them. Instead of forcing the optimizer to discover the geometry of the problem blindly, what if we baked the geometry directly into the optimization process a priori?

This is the premise of a fascinating new paper, “Training Deep Learning Models with Norm-Constrained LMOs.” The researchers propose a family of algorithms that move away from standard gradient descent and towards methods based on Linear Minimization Oracles (LMOs).

The result is SCION, an optimizer that:

- Often outperforms Adam and Muon.

- Allows hyperparameters (like learning rate) to transfer perfectly from tiny models to massive ones.

- Is memory efficient, requiring only one set of weights and gradients.

In this post, we will break down the math behind this approach, explain why “Norm-Constrained” optimization is a game-changer, and look at the impressive empirical results.

Background: The Geometry of Learning

To understand why this paper is important, we need to rethink how we calculate updates.

Euclidean vs. Non-Euclidean

Standard Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) assumes a Euclidean geometry. It takes a step in the direction of the negative gradient. However, the parameter space of a neural network is complex. A small change in one weight matrix might have a massive impact on the output, while a large change in another might do nothing.

Adaptive methods like Adam try to normalize these updates using second-moment estimates. But there is another way: changing the norm.

Instead of measuring the “size” of our update using the standard Euclidean distance (L2 norm), we can use norms that better reflect the structure of matrices, such as the Spectral Norm or the Infinity Norm.

The Linear Minimization Oracle (LMO)

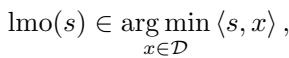

The core primitive of the algorithms proposed in this paper is the LMO.

In simple terms, if you have a constraint set \(\mathcal{D}\) (think of a shape, like a ball or a box), the LMO takes a direction vector \(s\) (like a gradient) and finds the point in that shape that minimizes the inner product with \(s\).

If the set \(\mathcal{D}\) is a norm-ball defined by radius \(\rho\):

Then the LMO finds the “corner” or boundary point of that ball that points most strongly in the direction of steepest descent.

Classically, LMOs are used in Conditional Gradient (Frank-Wolfe) methods for constrained optimization—where you must keep your parameters inside a specific region. This paper does something clever: it applies this logic to unconstrained deep learning problems.

The Method: uSCG and SCION

The authors introduce two main algorithmic frameworks: uSCG (Unconstrained Stochastic Conditional Gradient) and SCG (the constrained version).

Unconstrained SCG (uSCG)

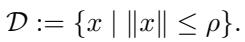

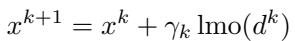

Typically, Frank-Wolfe algorithms update parameters using a convex combination (a weighted average). uSCG changes this. It uses the LMO to determine the direction and scale of the update, but adds it directly to the current weights, similar to SGD.

Here is the update rule for uSCG:

And here is how the “gradient” \(d^k\) is calculated using momentum:

What makes this powerful is that the LMO normalizes the update. Because the LMO always returns a point on the boundary of the norm-ball \(\mathcal{D}\), the magnitude of the update is fixed by the radius \(\rho\), regardless of how large or small the gradients are. This makes the algorithm incredibly robust to vanishing or exploding gradients.

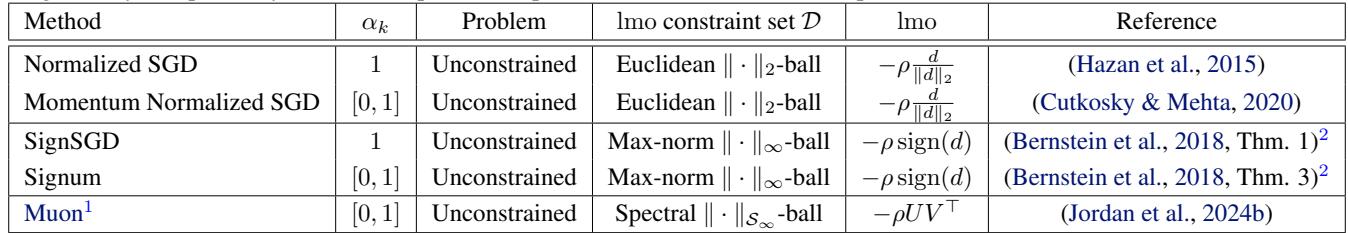

It turns out that many existing “exotic” optimizers are actually just specific instances of uSCG with different choices of norms!

As shown in Table 1, if you choose the Euclidean ball, you recover Normalized SGD. If you choose the Max-norm (infinity ball), you recover SignSGD. If you choose the Spectral ball, you get something very similar to the recent Muon optimizer.

SCION: Operator Norms for Deep Learning

The most significant contribution of the paper is SCION (Stochastic Conditional Gradient with Operator Norms).

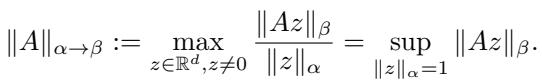

Neural networks are composed of layers that transform inputs to outputs. The “size” of a layer’s weight matrix \(W\) shouldn’t just be the sum of its squared entries (Frobenius norm). A better measure is how much the matrix can “stretch” a vector. This is the Operator Norm.

The authors propose using specific operator norms to define the geometry of the update.

By choosing the input norm \(\alpha\) and the output norm \(\beta\), we can derive specific LMOs for different layers.

The Spectral Norm (RMS \(\to\) RMS)

For hidden layers, the authors recommend the Spectral Norm (specifically, the mapping from RMS norm to RMS norm). The LMO for the spectral norm involves calculating the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of the gradient.

Why Spectral Norm? Because it controls the Lipschitz constant of the layer. It ensures that the signal flowing through the network doesn’t explode or vanish, regardless of the width of the layer. This is crucial for feature learning.

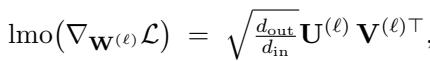

The Mix: ColNorm, Spectral, and Sign

Different layers have different roles. The authors suggest a hybrid configuration:

- Input Layer: Use ColNorm (Column-wise normalization) or Spectral Norm.

- Hidden Layers: Use Spectral Norm.

- Output Layer: Use Sign updates (Infinity Norm).

Table 2 summarizes these choices and their corresponding update rules (LMOs).

The “Killer Feature”: Zero-Shot Hyperparameter Transfer

One of the biggest headaches in Deep Learning is tuning the learning rate. You tune it on a small model, but when you scale up to a larger model (wider layers), the optimal learning rate shifts. You have to re-tune, which is expensive.

SCION solves this.

Because the updates are normalized by the spectral norm (which inherently accounts for the dimensions \(d_{in}\) and \(d_{out}\)), the optimal hyperparameters transfer perfectly across model widths.

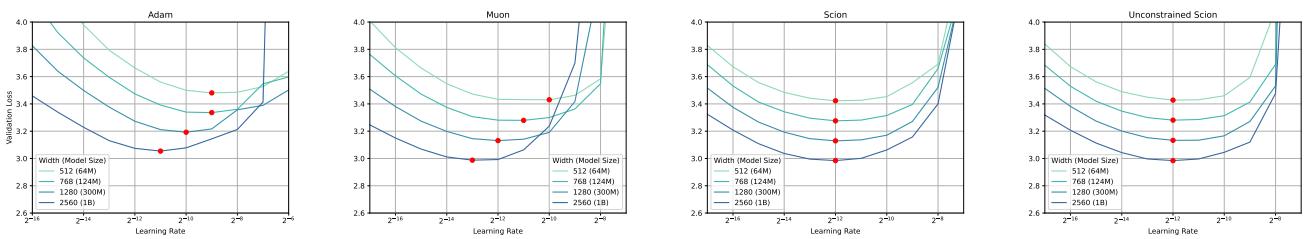

This isn’t just theory. Look at the experimental results on NanoGPT:

In Figure 1, look at the “Scion” and “Unconstrained Scion” plots. The curves for model widths ranging from 64M to 1B parameters align perfectly. The optimal learning rate (the lowest point of the curve) is exactly the same for all model sizes.

Compare this to Adam (top left), where the optimal learning rate drifts as the model gets wider. This means you can tune SCION on a cheap, small model and immediately train a massive model with the same settings.

Theoretical Guarantees

While we won’t dive too deep into the proofs, the paper provides rigorous convergence guarantees.

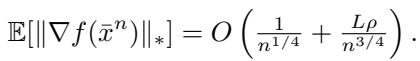

For uSCG, the convergence rate for non-convex problems (like deep learning) is derived as:

This \(O(n^{-1/4})\) rate matches the optimal convergence rate for stochastic non-convex optimization.

A key insight from the analysis is that uSCG does not require knowledge of the Lipschitz constant. In standard SGD, if your step size is too large relative to the curvature (Lipschitz constant), you diverge. Because uSCG normalizes updates via the LMO, the step size is robust.

Experiments and Results

The authors tested SCION against AdamW and Muon (a similar recent spectral-based optimizer) on various tasks, including training GPT models and Vision Transformers (ViT).

1. NanoGPT Performance

On training NanoGPT (a standard transformer benchmark), SCION achieves lower validation loss than AdamW and matches or beats Muon.

Crucially, SCION is more memory efficient. The implementation requires storing only one set of weights and one set of gradients (which can be in half-precision). It removes the need for the second-moment accumulator used in Adam, saving significant GPU memory.

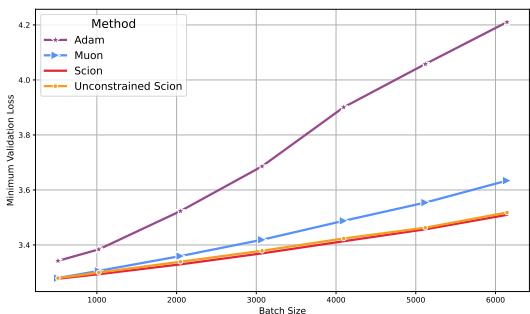

2. Batch Size Robustness

As we scale up training, we often want to use larger batch sizes to parallelize across more GPUs. However, many optimizers become unstable or generalize poorly at large batch sizes.

SCION exhibits remarkable robustness to large batch sizes.

In Figure 2, you can see that as the batch size increases (x-axis), the validation loss for Adam (purple) degrades significantly. Muon (blue) also degrades. SCION (red and orange), however, maintains low loss even at very large batch sizes.

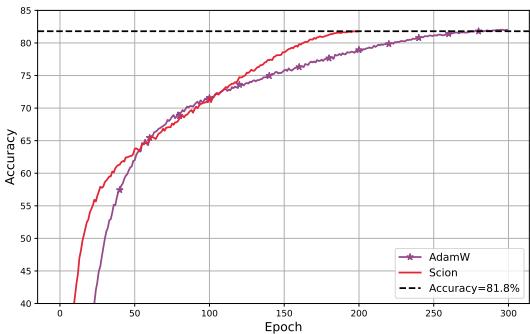

3. ImageNet Training

The benefits extend to Computer Vision. Training a Vision Transformer (ViT) on ImageNet, SCION reached the target accuracy in 30% fewer epochs than the baseline.

Because SCION supports larger critical batch sizes, it also resulted in a >40% wall-clock speedup.

4. Scaling to 3B Parameters

To prove the method scales, they trained a 3 Billion parameter GPT model.

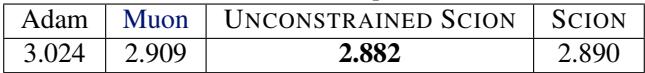

As shown in Table 5, Unconstrained SCION achieved the lowest validation loss compared to Adam and Muon.

Implementation: How it works in practice

Implementing SCION is surprisingly straightforward. For the spectral norm layers, we need to compute the LMO, which requires the top singular vectors of the gradient matrix. Computing a full SVD is too slow, so the authors use Newton-Schultz iterations—an iterative method that approximates the SVD very efficiently on the GPU.

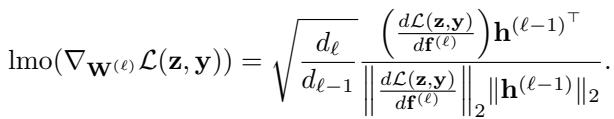

Here is the general algorithm for Unconstrained SCION:

Note: The image above shows the LMO calculation details, but the algorithmic loop is simple: Get gradients -> Update momentum -> Compute LMO (normalize) -> Update weights.

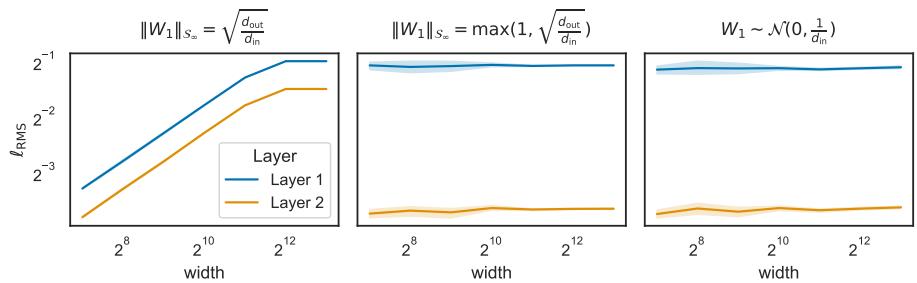

We also need to ensure the network is initialized correctly so that the norms are balanced at the start. The authors suggest a specific initialization strategy (like semi-orthogonal initialization) to match the spectral constraints.

Figure 4 shows that with the correct spectral scaling (middle and right plots), the activations remain stable regardless of width, whereas incorrect scaling (left) leads to exploding or vanishing signals.

Conclusion

The paper “Training Deep Learning Models with Norm-Constrained LMOs” offers a compelling alternative to the dominance of Adam. By stepping back and looking at the geometry of neural networks, the authors designed SCION, an optimizer that is:

- Geometry-Aware: It uses spectral and operator norms that fit the architecture of deep networks.

- Scale-Invariant: It solves the hyperparameter scaling problem, allowing zero-shot transfer from small to large models.

- Efficient: It saves memory and is robust to large batch sizes.

As we continue to train larger and larger models, the “black box” approach of adaptive optimizers may reach its limits. Methods like SCION, which respect the structure of the model a priori, represent the next logical step in the evolution of deep learning optimization.

If you are training Transformers or large ConvNets, SCION is definitely worth a look—especially if you want to save time on hyperparameter tuning and squeeze more performance out of your GPUs.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.07529/images/cover.png)