Introduction

We are currently witnessing a golden age of Multi-modal Large Language Models (MLLMs). Models like GPT-4o, Gemini, and Claude can analyze complex images, write poetry, and code entire applications. Naturally, the next frontier is embodied AI—taking these “brains” and putting them inside a robot (or a simulation of one) to navigate the physical world and manipulate objects.

The dream is a generalist robot that can understand a command like “clean up the kitchen,” see a mess, and figure out the thousands of tiny muscle movements required to tidy up. However, there is a significant gap between chatting about a task and physically doing it.

While we have many benchmarks for text generation and static image analysis, we lack a comprehensive, standardized way to measure how well these models perform as embodied agents. How good is GPT-4o at navigating a room? Can Claude-3.5 control a robotic arm to stack blocks?

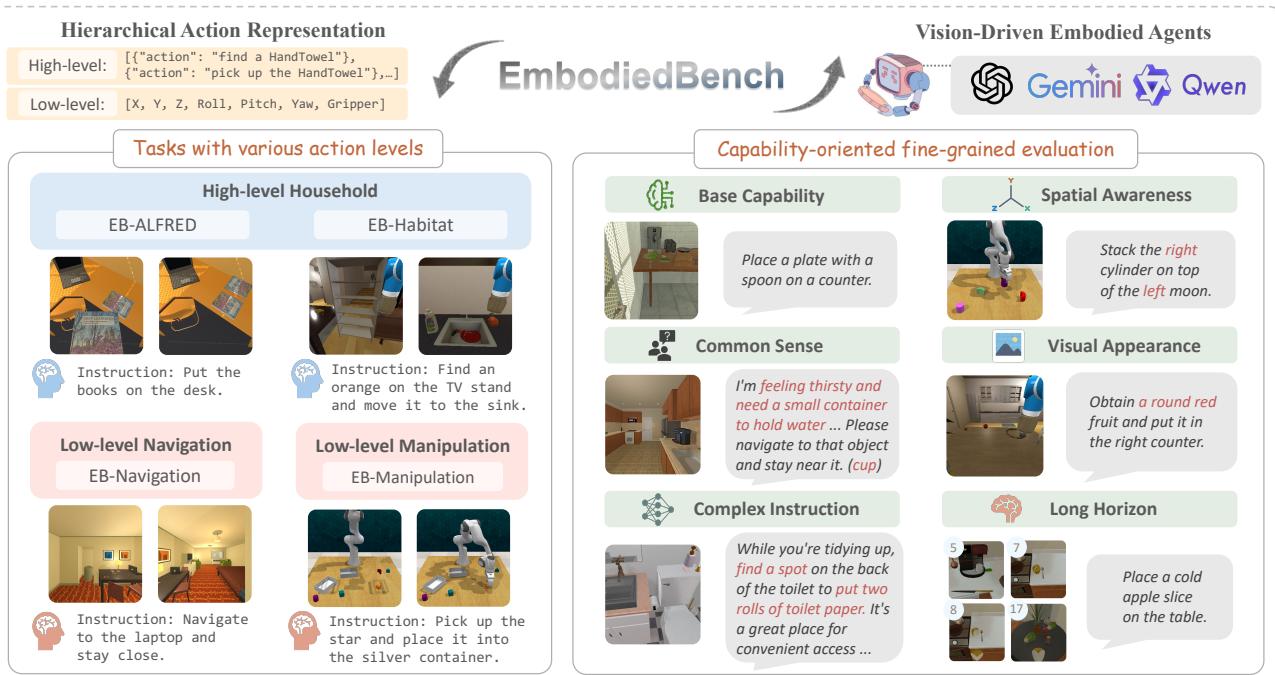

To answer these questions, researchers have introduced EMBODIEDBENCH. It is an extensive benchmark designed to rigorously evaluate vision-driven embodied agents. It covers 1,128 tasks across four different environments, testing everything from high-level reasoning (like deciding which object to pick up) to low-level atomic actions (like calculating the exact coordinates to move a gripper).

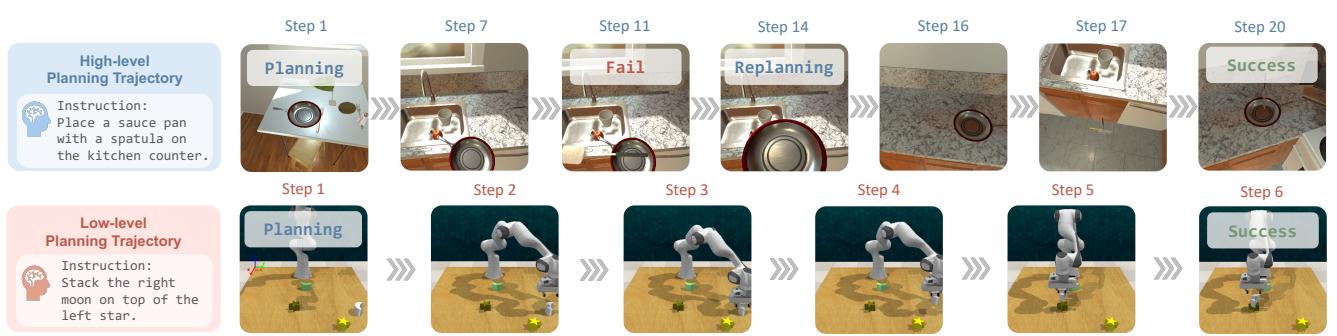

As shown in Figure 1 above, EMBODIEDBENCH introduces a critical distinction in evaluation: Hierarchical Action Levels (High vs. Low) and Capability-Oriented Evaluation (testing specific skills like spatial awareness or common sense). In this post, we will tear down the paper to understand how this benchmark works and, more importantly, what it reveals about the current state of AI robotics.

Background: The Embodied Evaluation Gap

Before diving into the method, we need to understand the landscape. Traditionally, embodied AI has been dominated by Reinforcement Learning (RL), where agents are trained for millions of steps on specific tasks. However, the rise of Foundation Models offers a different path: using pre-trained knowledge from the internet to solve tasks zero-shot or few-shot.

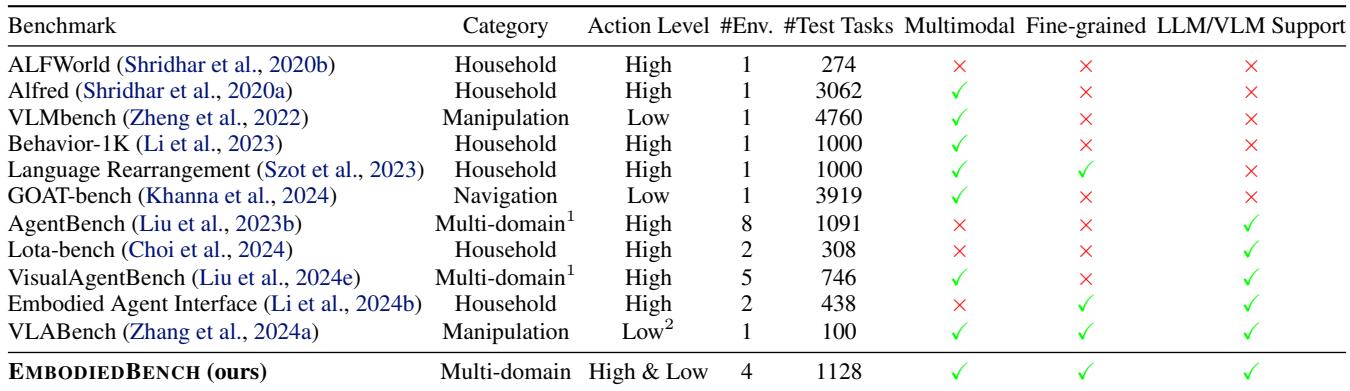

The problem is that existing benchmarks haven’t kept up with MLLMs.

- Text-Only Roots: Many benchmarks, like ALFWorld, are text-based games. They don’t test the vision part of the equation rigorously.

- Limited Scope: Benchmarks like VisualAgentBench exist, but they focus mostly on high-level planning (e.g., “Plan a wedding in this game”) rather than the nitty-gritty of robotic control.

- Missing Low-Level Assessment: Very few benchmarks test if an MLLM can output precise continuous control signals (like

[x, y, z, roll, pitch, yaw]).

The researchers compiled a comparison of related work, highlighting how EMBODIEDBENCH fills these gaps by including both high and low-level actions and a fine-grained capability assessment.

The Core Method: Inside EmbodiedBench

EMBODIEDBENCH is not just a single simulation; it is a suite of four distinct environments designed to test different aspects of robotic intelligence.

1. The Four Environments

The benchmark categorizes tasks based on the “level” of action required. This distinction is vital because telling a robot to “Pick up the apple” (High-Level) is computationally very different from calculating the inverse kinematics to move a gripper to coordinate (34, 55, 12) (Low-Level).

High-Level Tasks (The “Manager” Role):

- EB-ALFRED: Based on the ALFRED dataset, this environment simulates household tasks. The agent issues commands like

PickUp(Apple)orToggleOn(Lamp). It tests the agent’s ability to decompose a long instruction (e.g., “Heat the apple”) into a sequence of logical steps. - EB-Habitat: Focused on “Rearrangement” tasks. The robot must find objects in a house and move them to specific receptacles. It involves navigation and interaction but uses abstract commands like

Navigate(Kitchen)rather than joystick-like controls.

Low-Level Tasks (The “Operator” Role):

- EB-Navigation: Here, the training wheels come off. The agent must output atomic movements:

Move Forward 0.25m,Rotate Right 90 degrees, orTilt Camera. The goal is to find specific objects without a map, relying solely on visual input. - EB-Manipulation: This is the most granular environment. The agent controls a Franka Emika Panda robotic arm. It must output 7-dimensional vectors (

[x, y, z, roll, pitch, yaw, gripper]) to manipulate objects, such as stacking blocks or sorting shapes.

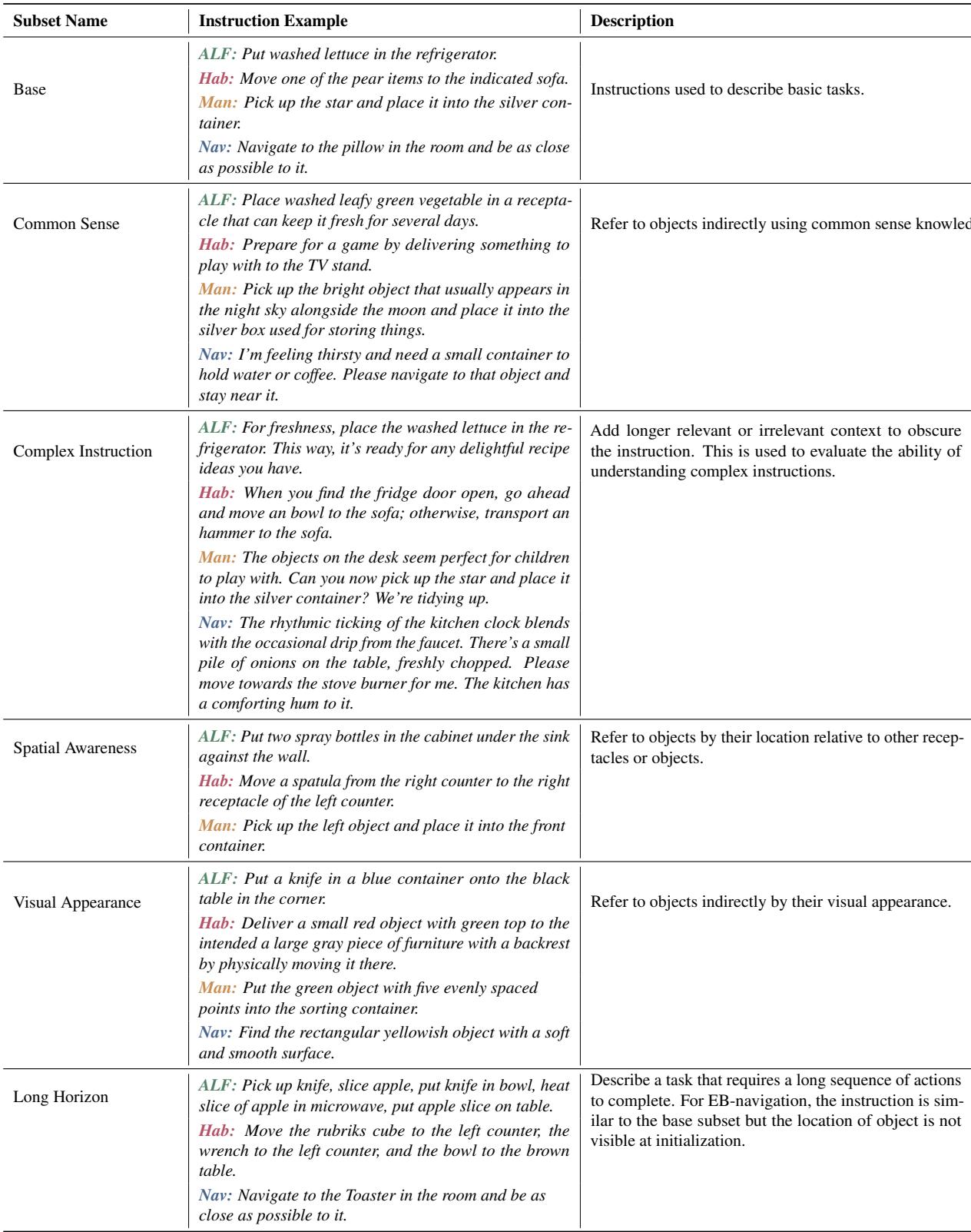

2. Capability-Oriented Subsets

A major contribution of this paper is moving away from a single “accuracy score.” Instead, they categorize tasks to diagnose why a model fails. They defined six specific capabilities:

- Base: Standard tasks (e.g., “Put the lettuce in the fridge”).

- Common Sense: Tasks requiring external knowledge (e.g., “Put the vegetable in the appliance that keeps food fresh” -> requires knowing a fridge keeps food fresh).

- Complex Instruction: Commands buried in irrelevant noise or long contexts.

- Spatial Awareness: Referring to objects by location (e.g., “The bottle left of the sink”).

- Visual Appearance: Referring to objects by look (e.g., “The red bowl”).

- Long Horizon: Tasks requiring massive sequences of 15+ steps.

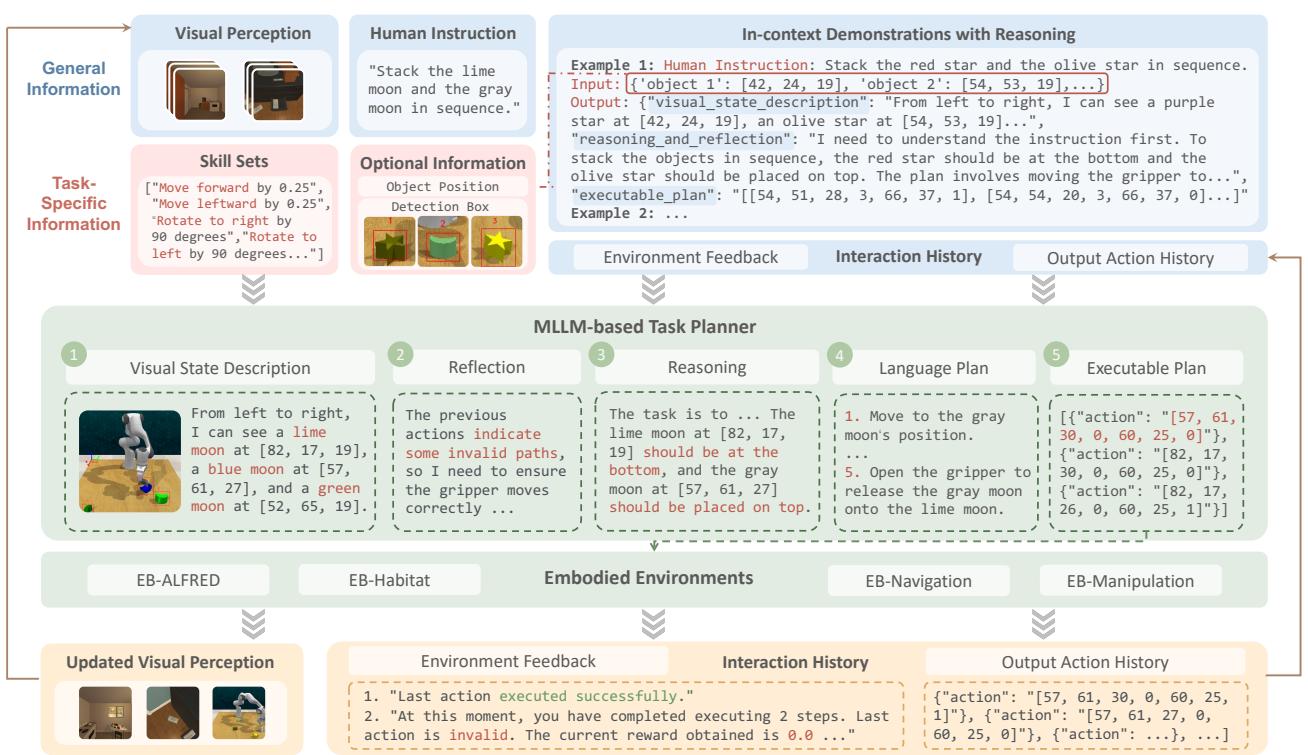

3. The Unified Agent Framework

How do you plug a chatbot into a robot? The researchers designed a unified “Vision-Driven Agent Pipeline.” This framework allows any MLLM (like GPT-4 or Llama-3-Vision) to function as a robot brain.

The process, illustrated below, follows a loop:

- Perception: The model receives the current view from the robot’s camera.

- Reflection: It looks at its history. Did the last action fail? Why?

- Reasoning: It thinks about the goal and the current state.

- Planning: It generates a high-level plan in language.

- Execution: It translates that plan into the specific JSON format required by the environment (e.g., specific action IDs or coordinates).

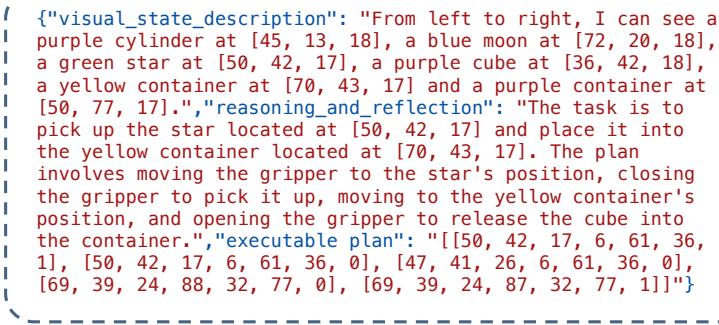

This pipeline supports multi-step planning. Instead of asking the LLM for just one move at a time (which is slow and expensive), the agent can generate a sequence of actions. For example, in the manipulation task shown in Figure 3 below, the agent plans a trajectory to stack a moon-shaped object on a star.

Experiments & Key Results

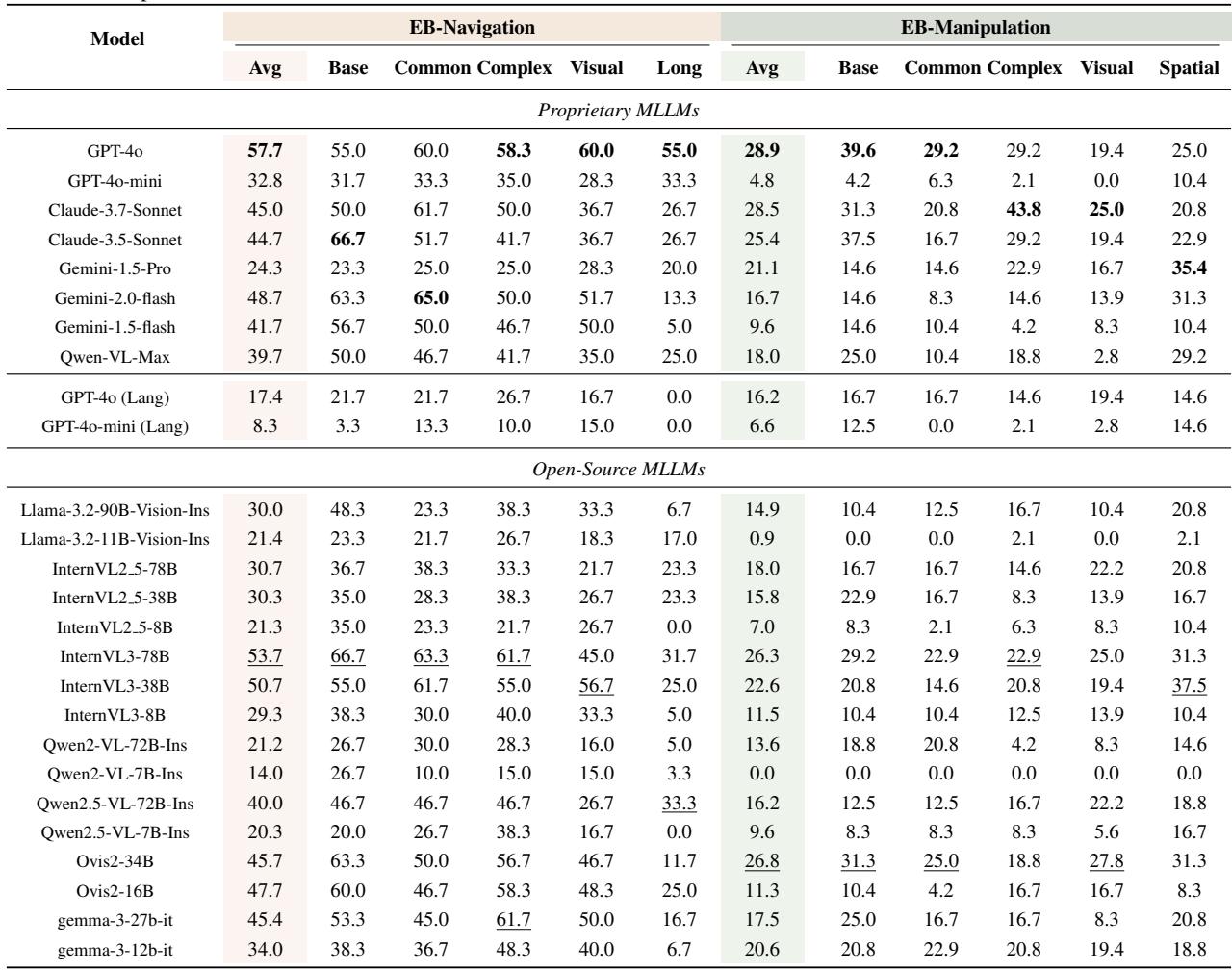

The team evaluated 24 models, including proprietary giants (GPT-4o, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, Gemini-1.5-Pro) and open-source contenders (InternVL, Llama-3.2-Vision).

1. High-Level vs. Low-Level Performance

The most striking finding is the performance disparity between high-level reasoning and low-level control.

- High-Level is Solvable: Current SOTA models are quite good at being “Managers.” On EB-ALFRED and EB-Habitat, models like Claude-3.5-Sonnet achieved success rates in the 60-70% range. They understand household logic well.

- Low-Level is Hard: When asked to be “Operators,” performance collapses. In EB-Manipulation (controlling the robot arm), even the best model (GPT-4o) only achieved a 28.9% success rate.

Table 3 below details these low-level results. Notice the “Lang” rows—these represent runs where visual input was removed.

2. The Role of Vision

The researchers performed an ablation study where they turned off the camera (the “Lang” rows in the table above).

- In High-Level Tasks: Surprisingly, removing vision didn’t hurt much. Sometimes it even helped. This suggests that high-level benchmarks like ALFRED rely heavily on language cues and metadata, and models might be “gaming” the benchmark using text rather than truly seeing.

- In Low-Level Tasks: Vision is non-negotiable. Performance dropped by 40-70% without images. In navigation, for example, GPT-4o dropped from 57.7% to 17.4% without vision. You cannot navigate a room if you cannot see the obstacles.

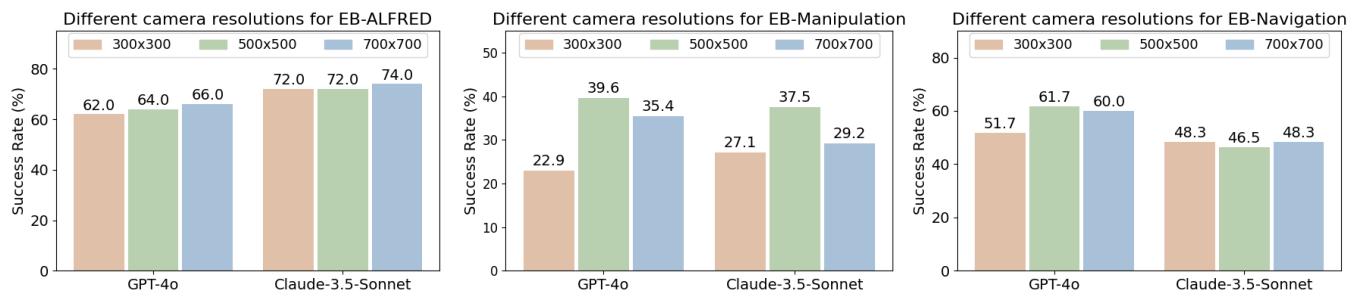

3. Visual-Centric Ablations: What Helps?

Since low-level tasks are the bottleneck, the researchers investigated what visual factors influence success.

Camera Resolution: You might think “higher resolution is always better,” but the results in Figure 7 show a bell curve. While jumping from 300x300 to 500x500 helped significantly, increasing to 700x700 often hurt performance. This is likely because excessively high resolutions introduce too much visual noise for the MLLM to process relevantly, or perhaps resizing artifacts interfere with the model’s pre-trained encodings.

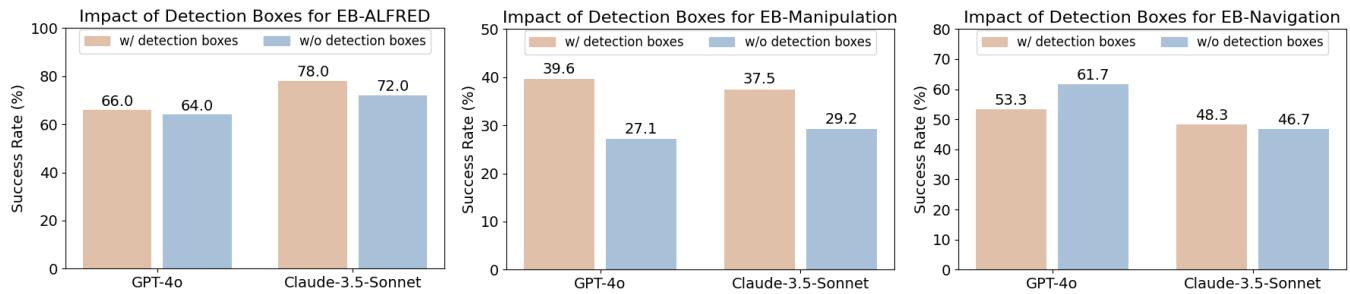

Detection Boxes: Does drawing bounding boxes around objects help? As shown in Figure 8, it depends on the task.

- Manipulation: Yes. Bounding boxes significantly improved success (e.g., GPT-4o jumped from ~27% to ~40%). Accurate picking requires knowing exactly where the object is.

- Navigation: No. Adding boxes actually hurt performance. In navigation, the agent needs to see the scene geometry (floor, walls, obstacles). Cluttering the view with boxes likely obscured crucial pathfinding cues.

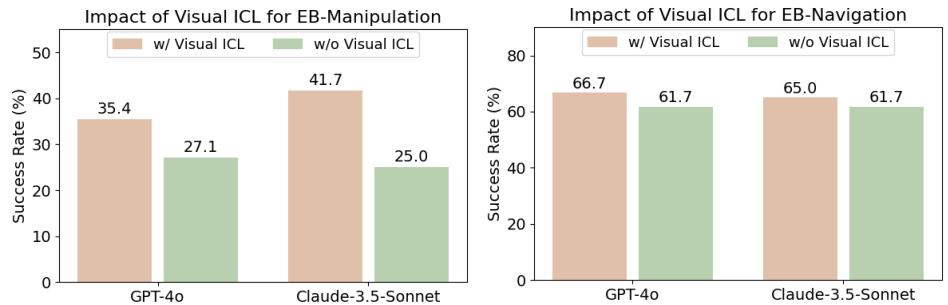

Visual In-Context Learning (Visual ICL): This was perhaps the most promising finding. Standard “In-Context Learning” involves showing the model text examples of the task. “Visual ICL” involves showing the model images of successful actions alongside the text.

The researchers provided the agents with visual examples of successful manipulation and navigation steps (see Figure 15).

The result? A massive performance boost. As Figure 16 shows, adding Visual ICL improved Claude-3.5-Sonnet’s manipulation score from 25.0% to 41.7%. This suggests that MLLMs are very capable of learning visual physics and spatial relationships from just a few examples, a technique that could be key to solving the low-level control problem.

4. Error Analysis

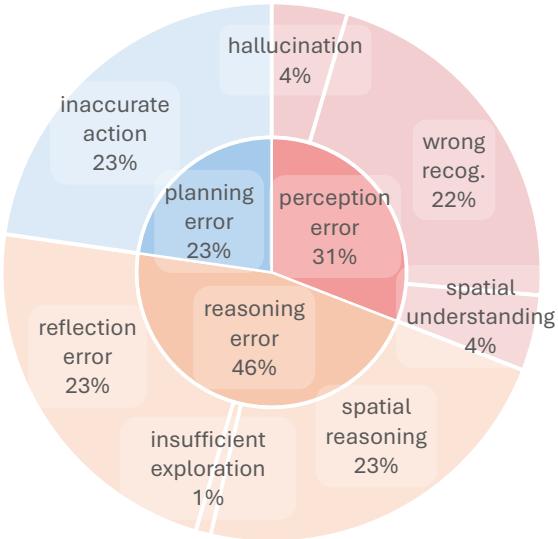

Why do the models fail? The team categorized errors into Perception, Reasoning, and Planning.

In EB-Navigation (Figure 17 below), “Inaccurate Action” and “Spatial Reasoning” were dominant errors. The models often knew where to go but couldn’t calibrate the exact amount of movement required (e.g., rotating 90 degrees when only 45 was needed), or they hallucinated obstacles that weren’t there.

In EB-ALFRED (Figure 6 from the paper data), “Planning Errors” dominated. The models would often skip necessary steps (like opening a microwave before trying to put food in it) or generate invalid actions that the simulator rejected.

Conclusion & Implications

EMBODIEDBENCH serves as a reality check for the field of AI robotics. While MLLMs are impressive reasoning engines, they are not yet competent robot controllers out-of-the-box.

Key Takeaways:

- The “Brain” is ready, the “Hands” are not: Models excel at high-level planning but struggle with the spatial precision required for manipulation and navigation.

- Vision is strictly required for control: While you can “fake” high-level planning with good text descriptions, low-level control demands accurate visual processing.

- Visual Prompting is powerful: Visual In-Context Learning is a highly effective, low-cost way to improve performance without retraining models.

For students and researchers, this paper highlights a clear path forward: the next generation of embodied agents needs better spatial grounding. We need models that don’t just recognize what an object is, but understand where it is in 3D space and how to move a physical body to interact with it. EMBODIEDBENCH provides the standardized yardstick we need to measure that progress.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.09560/images/cover.png)