Introduction: The Paradox of Long-Context Attention

The Transformer architecture has revolutionized natural language processing, but it harbors a well-known secret: it is notoriously inefficient at scale. The culprit is the self-attention mechanism. In its standard form, every token in a sequence attends to every other token. If you double the length of your input document, the computational cost doesn’t just double—it quadruples. This is the infamous \(O(n^2)\) complexity.

For years, researchers have known that this dense attention is often wasteful. When you read a book, you don’t focus on every single word on every previous page simultaneously to understand the current sentence. You focus on a few key context clues. In machine learning terms, attention probability distributions are often sparse—peaking around a few relevant tokens while the rest are near-zero noise.

While mathematically elegant “sparse attention” mechanisms (like \(\alpha\)-entmax) exist to zero out that noise, they have suffered from a practical paradox: implementing them on GPUs often makes the model slower, not faster. Standard hardware is optimized for dense matrix multiplications, and the logic required to figure out what to ignore usually takes longer than just doing the math for everything.

Enter ADASPLASH.

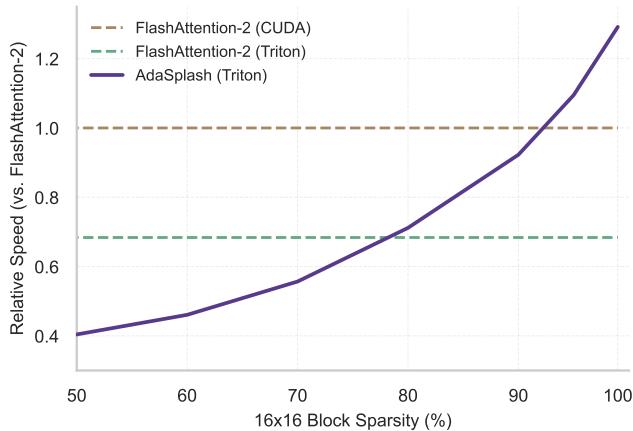

As shown in Figure 1, ADASPLASH is a new algorithm and hardware implementation that finally aligns the theoretical benefits of sparsity with hardware reality. Unlike previous methods where sparsity was a computational burden, ADASPLASH actually gets faster as the attention becomes sparser, eventually outperforming even the highly optimized FlashAttention-2.

In this post, we will deconstruct the ADASPLASH paper. We’ll explore the math behind “true” sparsity, the algorithmic tricks used to compute it efficiently, and the custom GPU kernels that allow Transformers to skip the noise and focus on what matters.

1. Background: The Problem with Softmax

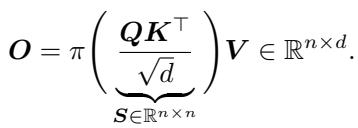

To understand why ADASPLASH is necessary, we first need to look at the standard attention mechanism. The core of a Transformer is the dot-product attention:

Here, \(Q, K, V\) are the Query, Key, and Value matrices. The function \(\pi\) typically represents the softmax transformation.

The Softmax Issue

Softmax is designed to turn scores into probabilities that sum to 1. However, softmax has a specific property: it never produces a zero. Even if a token is completely irrelevant, softmax will assign it a tiny, non-zero probability (e.g., \(0.00001\)).

In short sequences, this is negligible. In long sequences (e.g., 32k or 100k tokens), thousands of these tiny values accumulate. This leads to two problems:

- Noise: The relevant signal gets diluted by the “long tail” of irrelevant tokens.

- Computational Waste: The GPU must load and compute interactions for every single token pair, even the irrelevant ones.

The Hardware Bottleneck

Recently, FlashAttention revolutionized how we compute standard attention. It recognized that the bottleneck wasn’t just the arithmetic operations (FLOPs), but the memory bandwidth (HBM reads/writes). FlashAttention solved this by “tiling” the computation—loading small blocks of \(Q, K, V\) into the fast on-chip SRAM, computing attention, and writing back only the result, without ever materializing the massive \(N \times N\) attention matrix in slow memory.

However, FlashAttention assumes dense softmax. If we want to use sparse attention to save time, we need a way to mathematically force probabilities to zero and a hardware kernel that knows how to skip them efficiently.

2. Mathematical Foundation: \(\alpha\)-entmax

To replace softmax with something that allows for zeros, the authors utilize the \(\alpha\)-entmax transformation. This is a generalization of softmax that maps a vector of scores to a probability distribution, but with a crucial difference: it is sparse.

![]\n\\alpha \\mathrm { - e n t m a x } \\left( s \\right) = \\left[ ( \\alpha - 1 ) s - \\tau \\mathbf { 1 } \\right] _ { + } ^ { 1 / \\alpha - 1 } ,\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/003.jpg#center)

In this equation:

- \([\cdot]_+\) is the ReLU function (keeping values positive).

- \(\tau\) is a normalizing threshold.

- \(\alpha\) controls sparsity.

- If \(\alpha \to 1\), it behaves like softmax (dense).

- If \(\alpha = 2\), it becomes sparsemax, which is highly sparse.

- Intermediate values (e.g., \(\alpha = 1.5\)) offer a balance.

The key takeaway is that if a score \(s_i\) is low enough (specifically, if \((\alpha - 1)s_i \le \tau\)), the probability becomes exactly zero.

The Computational Hurdle

Ideally, we would just apply this formula. But there is a catch: we don’t know \(\tau\). The threshold \(\tau\) must be chosen precisely such that the resulting probabilities sum exactly to 1. Finding \(\tau\) requires finding the root of this equation:

![]\nf ( \\tau ) = \\sum _ { i } \\left[ ( \\alpha - 1 ) s _ { i } - \\tau \\right] _ { + } ^ { 1 / ( \\alpha - 1 ) } - 1 .\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/004.jpg#center)

We need to find \(\tau\) where \(f(\tau) = 0\). This is an implicit equation that must be solved iteratively for every single row of the attention matrix. If this solving process is slow, the whole attention mechanism becomes slower than standard softmax, defeating the purpose.

3. Innovation 1: The Hybrid Halley-Bisection Algorithm

Existing implementations typically use a Bisection algorithm to find \(\tau\). Bisection works by defining a range (low and high bounds) and repeatedly cutting it in half.

![]\nB _ { f } ( \\tau ) = \\left{ \\begin{array} { l l } { ( \\tau _ { \\mathrm { l o } } , \\tau ) } & { \\mathrm { i f ~ } f ( \\tau ) < 0 , } \\ { ( \\tau , \\tau _ { \\mathrm { h i } } ) } & { \\mathrm { o t h e r w i s e } , } \\end{array} \\right.\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/005.jpg#center)

While reliable, bisection converges linearly. It takes many iterations to get a precise value. In a high-speed GPU kernel, every iteration costs precious cycles reading data.

Halley’s Method

To speed this up, the authors propose using Halley’s Method. Unlike bisection, which blindly cuts the range in half, Halley’s method uses information about the curve’s slope (derivative) and curvature (second derivative) to make an educated guess about where the zero is.

The update rule looks like this:

![]\nH _ { f } ( \\tau ) = \\tau - \\frac { 2 f ( \\tau ) f ^ { \\prime } ( \\tau ) } { 2 f ^ { \\prime } ( \\tau ) ^ { 2 } - f ( \\tau ) f ^ { \\prime \\prime } ( \\tau ) } ,\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/006.jpg#center)

The derivatives are computationally cheap to obtain because they are just sums over the input scores:

![]\n\\begin{array} { l } { { f ^ { \\prime } ( \\tau ) = - { \\displaystyle \\frac { 1 } { \\alpha - 1 } } \\sum _ { i } \\left[ ( \\alpha - 1 ) s _ { i } - \\tau \\right] _ { + } ^ { 1 / ( \\alpha - 1 ) - 1 } , } } \\ { { f ^ { \\prime \\prime } ( \\tau ) = { \\displaystyle \\frac { 2 - \\alpha } { ( \\alpha - 1 ) ^ { 2 } } } \\sum _ { i } \\left[ ( \\alpha - 1 ) s _ { i } - \\tau \\right] _ { + } ^ { 1 / ( \\alpha - 1 ) - 2 } . } } \\end{array}\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/007.jpg#center)

The Hybrid Approach

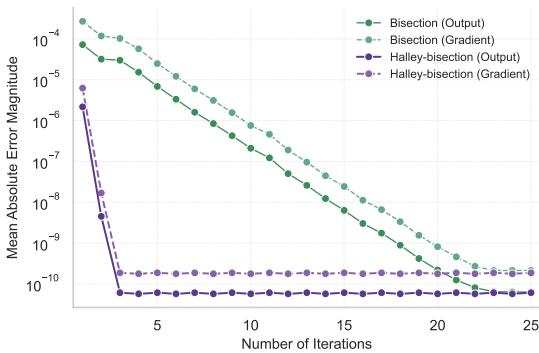

Halley’s method is incredibly fast (cubic convergence) when it works, but it can be unstable if the initial guess is far off. To get the best of both worlds, the authors introduce a Hybrid Halley-Bisection algorithm.

- Attempt a Halley update.

- Check if the new \(\tau\) falls within the current valid bounds.

- If yes, keep it (fast jump).

- If no, fall back to a Bisection step (guaranteed safety).

The result is a dramatic reduction in the number of iterations required to reach machine precision.

As Figure 2 shows, the Halley-based method (purple/red lines) drives the error to zero in just a few iterations, whereas standard bisection (blue/orange lines) drags on significantly longer.

4. Innovation 2: The ADASPLASH Kernel

Having a fast math equation is one thing; making it run fast on a GPU is another. The authors implemented ADASPLASH using Triton, a language designed for writing high-performance GPU kernels.

The core strategy mirrors FlashAttention: Tiling. The input matrices \(Q\) and \(K\) are split into blocks. These blocks are loaded from HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) to SRAM (fast cache).

Forward Pass with Block Sparsity

The algorithm proceeds in steps:

- Compute \(\tau\) via Blocks: The function \(f(\tau)\) is additive. This means we can compute partial sums for different blocks of \(K\) and aggregate them to find the threshold \(\tau\).

![]\nf ( \\pmb { \\tau } _ { i } ) = \\sum _ { j = 1 } ^ { T _ { c } } f ( \\pmb { \\tau } _ { i } ; \\pmb { S } _ { i } ^ { ( j ) } )\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/009.jpg#center)

- Dynamic Block Masking: This is the game-changer. Once an approximate \(\tau\) is found for a row block of Queries (\(Q_i\)), the algorithm checks which Key blocks (\(K_j\)) will actually result in non-zero probabilities.

If a block’s attention scores are all below the threshold \(\tau\), the entire block will be zero after \(\alpha\)-entmax. The algorithm marks this in a binary mask matrix \(M\):

![]\nM _ { i j } = \\left{ \\begin{array} { l l } { 1 } & { \\mathrm { i f } \\ \\exists _ { i ^ { \\prime } \\in \\mathbb { Z } ( i ) , j ^ { \\prime } \\in \\mathcal { I } ( j ) } : S _ { i ^ { \\prime } , j ^ { \\prime } } > \\tau _ { i ^ { \\prime } } , } \\ { 0 } & { \\mathrm { o t h e r w i s e } , } \\end{array} \\right.\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/010.jpg#center)

- The Pointer-Increment Lookup Table: Using the mask \(M\), ADASPLASH builds a lookup table. When computing the final output \(O = PV\), the kernel consults this table.

- If \(M_{ij} = 0\), the kernel skips loading the Value block (\(V_j\)) and skips the matrix multiplication entirely.

- This effectively prunes the computation dynamically based on the data.

The Backward Pass (Training)

Training requires calculating gradients. ADASPLASH splits the backward pass into separate kernels for efficient processing. It leverages the sparsity of the Jacobian of the \(\alpha\)-entmax function:

![]\n\\frac { \\partial \\alpha \\mathrm { - e n t m a x } ( s ) } { \\partial s } = \\operatorname { D i a g } ( \\pmb { u } ) - \\frac { \\pmb { u } \\pmb { u } ^ { \\top } } { \\Vert \\pmb { u } \\Vert _ { 1 } } ,\n[](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/011.jpg#center)

Because the forward pass stored the block mask \(M\) (or the lookup tables), the backward pass can also skip gradients for blocks that were zeroed out. This results in massive savings during training.

![]\n\\begin{array} { l } { { \\displaystyle d { \\pmb Q } _ { i } = \\sum _ { j = 1 } ^ { n } U _ { i j } \\left( d P _ { i j } - \\delta _ { i } \\right) { \\pmb K } _ { j } } } \\ { { \\displaystyle d { \\pmb K } _ { j } = \\sum _ { i = 1 } ^ { n } U _ { i j } \\left( d P _ { i j } - \\delta _ { i } \\right) { \\pmb Q } _ { i } } } \\end{array}\n()](/en/paper/2502.12082/images/031.jpg#center)

As seen in the gradient equations above, the computation iterates only over the valid interactions, ignoring the sparse zeros.

5. Experiments & Results

Does this complex architecture actually pay off? The authors tested ADASPLASH across synthetic benchmarks and real-world NLP tasks.

Efficiency Benchmarks

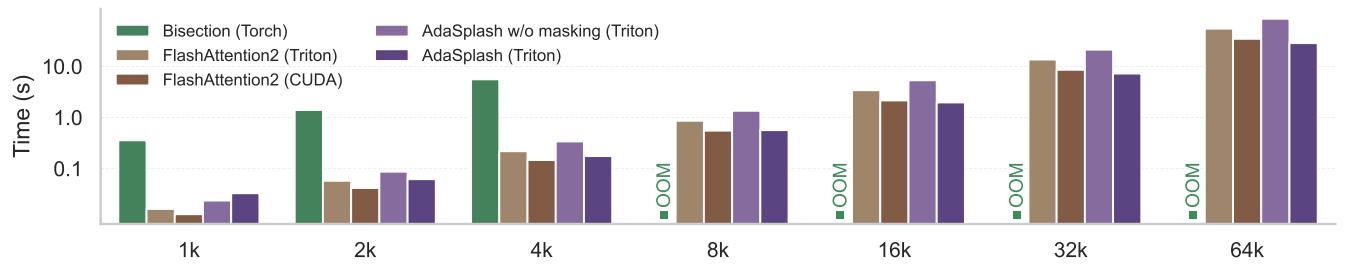

The most striking result is the runtime comparison.

In Figure 3, look at the purple line (AdaSplash (Triton)).

- Scalability: While standard PyTorch implementations (blue) crash with Out-Of-Memory (OOM) errors at sequence lengths of 8k, ADASPLASH scales gracefully up to 64k.

- Speed: It is significantly faster than standard FlashAttention-2 (Triton implementation) at higher sparsity levels. Note that standard FlashAttention (CUDA) is slightly faster at short sequences because it is highly optimized C++ code, but ADASPLASH closes the gap and eventually wins as sequence length (and thus sparsity) increases.

Real-World Performance

It’s not enough to be fast; the model must also be accurate. The researchers integrated ADASPLASH into RoBERTa, ModernBERT, and GPT-2.

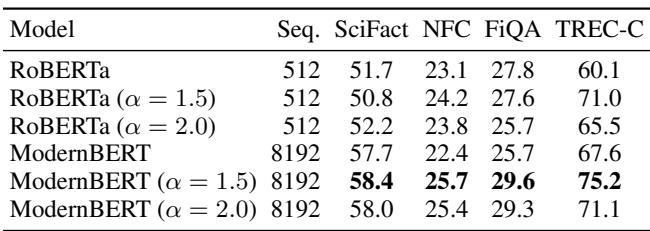

Retrieval Tasks (BEIR)

For single-vector retrieval, identifying the exact relevant information is crucial. Sparse attention shines here.

ModernBERT with \(\alpha=1.5\) (using ADASPLASH) consistently outperforms the dense ModernBERT baseline. The sparsity likely helps the model filter out noise in the retrieval documents.

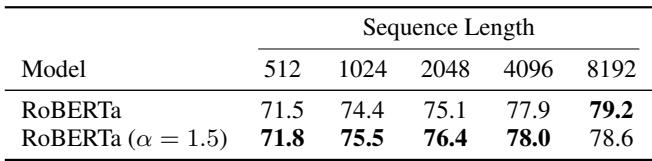

Long Document Classification

On the ECtHR dataset (legal judgment prediction), the ability to handle long contexts is vital.

ADASPLASH (RoBERTa \(\alpha=1.5\)) matches or exceeds the standard RoBERTa performance, particularly at longer sequence lengths (8192).

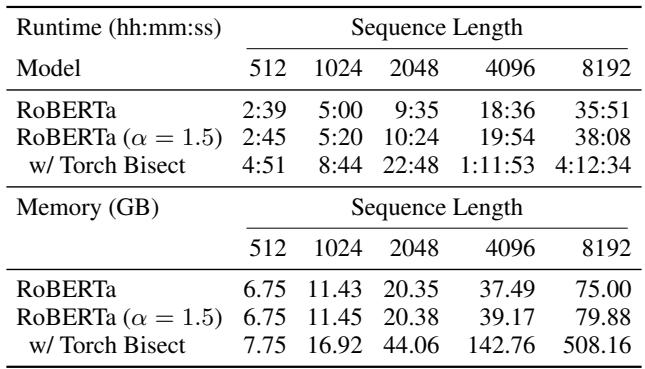

Critically, look at the resource usage:

Standard Bisection (the old way to do sparse attention) took 4 hours and 12 minutes for one epoch at sequence length 8192. ADASPLASH took 38 minutes. That is a massive difference in usability.

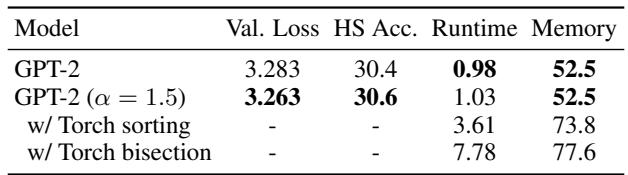

Language Modeling (GPT-2)

Finally, tested on generative modeling (GPT-2):

The sparse model achieves slightly better validation loss and accuracy on HellaSwag compared to the dense baseline, with virtually identical runtime and memory usage.

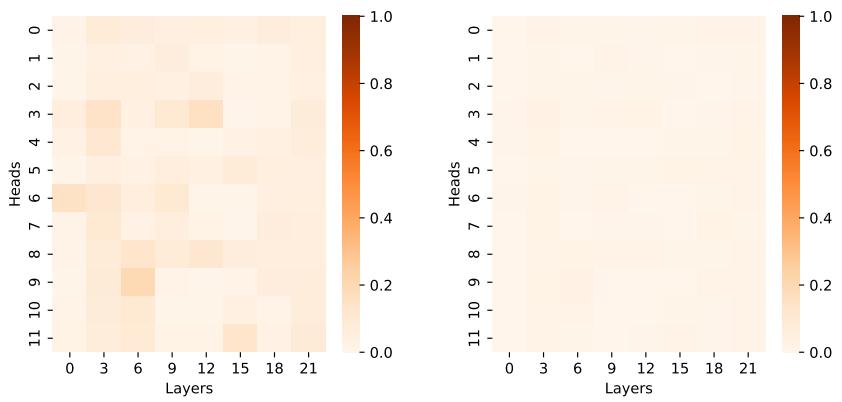

Visualizing the Sparsity

Does the model actually learn to be sparse?

Yes. The heatmaps above show the ratio of non-zero scores. In ModernBERT (Figure 5), we see extremely high sparsity (dark red indicates high density, light colors indicate sparsity). Many heads are operating with very few active connections, proving that the computation skipped by ADASPLASH is indeed substantial.

Conclusion: The Future is Sparse

The ADASPLASH paper represents a significant step forward for Transformer efficiency. For years, the community has known that attention is sparse—that we don’t need to look at everything to understand something. However, our hardware (GPUs) and software (dense kernels) forced us to process zeros anyway.

ADASPLASH breaks this cycle by:

- Solving the Math Faster: Using a Hybrid Halley-Bisection algorithm to find the sparsity threshold rapidly.

- Optimizing the Hardware: Using custom Triton kernels with block masking to physically skip computations for irrelevant data.

The implications are exciting. By removing the computational penalty of sparse attention, ADASPLASH opens the door for training models on much longer contexts without requiring massive clusters of H100s. It turns sparsity from a theoretical nicety into a practical acceleration strategy.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.12082/images/cover.png)