Rock, Paper, LLM? Why AI Judges Are Confused and How to Fix It

If you have ever tried to grade creative writing essays, you know how subjective it can be. Is Essay A better than Essay B? Maybe. But if you compare Essay B to Essay C, and then C to A, you might find yourself in a logical loop where every essay seems better than the last in some specific way. This is the problem of non-transitivity, and it turns out, Artificial Intelligence suffers from it too.

As Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4, Claude, and Llama become more capable, evaluating them has become a massive bottleneck. We can’t rely solely on human annotation anymore—it’s too slow and too expensive. The industry standard has shifted to “LLM-as-a-Judge,” where a powerful model (like GPT-4) acts as the teacher, grading the responses of other models.

Typically, this is done by comparing a new model against a fixed baseline. But a new paper, “Investigating Non-Transitivity in LLM-as-a-Judge,” reveals a critical flaw in this approach: LLM judges act a lot like players in a game of Rock-Paper-Scissors. This non-transitive behavior makes leaderboards unstable and rankings unreliable.

In this post, we will deep-dive into this research, exploring why LLM judges get confused, the mathematics behind “soft” non-transitivity, and the tournament-style solutions proposed to fix it.

1. The “Gold Standard” Problem

To understand the paper, we first need to understand the status quo. How do we currently know if Llama-3 is better than Mistral-Large?

For open-ended tasks (like “Write a poem about rust” or “Explain quantum physics to a toddler”), there is no single correct answer. You cannot just check an answer key. The current industry standard is Pairwise Comparison.

The Baseline-Fixed Framework

In frameworks like AlpacaEval, we take a target model (say, a new open-source model) and a fixed baseline model (usually an older version of GPT-4). We feed a prompt to both, get two answers, and ask a Judge (GPT-4-Turbo) to pick the winner.

The ranking is simple: Win Rate against Baseline.

If Model A beats the baseline 60% of the time, and Model B beats the baseline 70% of the time, we declare Model B the winner.

The Hidden Assumption: Transitivity

This logic relies on a mathematical property called transitivity.

- If Model B > Baseline

- And Baseline > Model A

- Then logic dictates that Model B > Model A.

If this assumption holds, using a fixed baseline is efficient and effective. But what if it doesn’t? What if Model A actually beats Model B in a head-to-head match, despite having a lower win rate against the baseline?

This is where the research begins. As illustrated below, the authors highlight the danger of the “Baseline-Fixed” approach versus the solution they propose (Round-Robin).

Figure 1: On the left, a baseline-fixed framework fails when preferences are inconsistent. On the right, a round-robin tournament captures the full picture.

Figure 1: On the left, a baseline-fixed framework fails when preferences are inconsistent. On the right, a round-robin tournament captures the full picture.

If the judge favors A over B, B over C, but C over A, we have a cycle. If you use Model B as your baseline, A looks like a loser (because C beats A). If you use Model C as your baseline, A looks like a winner. The ranking depends entirely on who you pick as the reference point.

2. Investigating Non-Transitivity

The researchers set out to quantify just how bad this problem is. They looked at two types of non-transitivity: Hard and Soft.

Hard Non-Transitivity (The Cycle)

This is the classic logical violation.

\[ m _ { A } \succ m _ { B } , m _ { B } \succ m _ { C } , m _ { A } \prec m _ { C } \](Where \(\succ\) means “beats” and \(\prec\) means “loses to”)

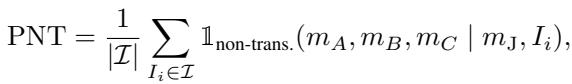

To measure this, the authors defined the Percentage of Non-Transitive (PNT) cases. They simply count how often these logical loops occur in the data.

However, LLMs rarely give a binary “Yes/No.” They output probabilities (logits). A model might be 51% sure A is better than B. This leads to the second, more subtle type of error.

Soft Non-Transitivity

Even if a strict “cycle” doesn’t exist, the magnitude of the preference can be inconsistent.

Imagine:

- The Judge thinks A is massively better than B.

- The Judge thinks B is slightly better than C.

- Transitive logic suggests the Judge should think A is massively better than C.

If the Judge instead thinks A is only barely better than C, the “strength” of the preference has violated transitivity. To capture this, the authors introduce a metric called Soft Non-Transitivity Deviation (SNTD).

This metric uses Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) to measure the distance between the actual observed win rate and the expected win rate if the model were perfectly logical.

The Smoking Gun: Sensitivity to Baselines

So, does this actually affect rankings? The authors ran a massive experiment comparing 20 different models (like GPT-4o, Claude 3, Llama 3) against each other.

The heatmap below is striking. Each column represents a ranking of models calculated using a different model as the baseline (the rows). If transitivity held perfectly, the colors (rankings) should be roughly consistent regardless of which row (baseline) you look at.

Figure 2: The varying colors in columns indicate that changing the baseline model significantly alters the win rates and rankings of the target models.

Figure 2: The varying colors in columns indicate that changing the baseline model significantly alters the win rates and rankings of the target models.

The result? Inconsistency. For example, looking at the figure, the win rates fluctuate wildly depending on whether Llama-3-70B or Claude-3-Opus is the baseline. This proves that “Win Rate against Baseline” is a volatile metric.

3. Why is the Judge Confused?

The paper identifies two main culprits driving this non-transitive behavior: Model Similarity and Position Bias.

The “Close Call” Problem

Non-transitivity peaks when the models being compared are similar in capability. When a strong model fights a weak model, the Judge is usually consistent. But when two high-tier models (like GPT-4o and Claude 3 Opus) face off, the Judge struggles to distinguish them, leading to noisy, cyclic preferences.

The heatmap below visualizes this. The axes represent the performance gap between models. Notice how the bright yellow/green spots (high non-transitivity) are clustered around the center (the origin), where the performance gap is zero.

Figure 3: Non-transitivity becomes severe when the performance gap between models is small (near the origin).

Figure 3: Non-transitivity becomes severe when the performance gap between models is small (near the origin).

Position Bias

LLMs have a known bias: they often prefer the first answer they see (or sometimes the second), regardless of quality. The authors found that Position Bias is a massive driver of non-transitivity, especially for weaker judges like GPT-3.5.

Figure 4: GPT-3.5 (right) is heavily influenced by position bias compared to GPT-4 (left). Bias mitigation (position switching) helps, but doesn’t solve it entirely.

Figure 4: GPT-3.5 (right) is heavily influenced by position bias compared to GPT-4 (left). Bias mitigation (position switching) helps, but doesn’t solve it entirely.

The authors tried “Position Switching”—running the evaluation twice with the answers swapped (A vs B, then B vs A). While this helps, it doesn’t eliminate the underlying issue that the judge’s internal reasoning can be circular.

4. The Solution: Tournaments and The Bradley-Terry Model

Since relying on a single baseline is flawed, the authors propose a Baseline-Free approach.

Step 1: Round-Robin Tournaments

In a round-robin tournament, every model plays against every other model. If you have 20 models, you run pairwise comparisons for every possible combination. This removes the dependency on any single “reference” model.

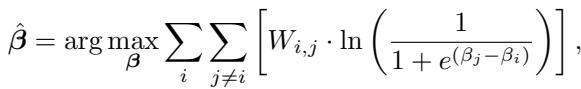

Step 2: The Bradley-Terry Model

Once we have all these match results, how do we rank them? We can’t just count wins, because beating a strong opponent should be worth more than beating a weak one.

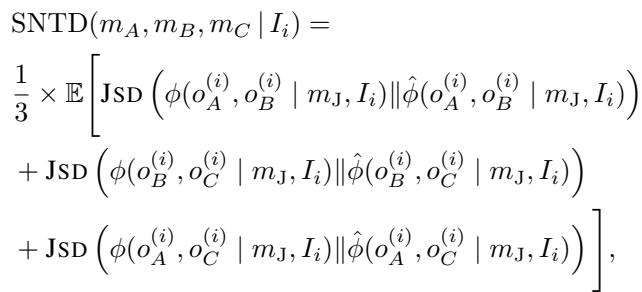

The authors utilize the Bradley-Terry (BT) model, a statistical approach often used in sports rankings (similar to Elo). The BT model assumes that the probability of Model \(i\) beating Model \(j\) depends on their latent “strength” scores (\(\beta_i\) and \(\beta_j\)).

The goal is to find the set of strength scores (\(\beta\)) that maximizes the likelihood of the observed tournament results.

Once we have these \(\beta\) coefficients, we can convert them into an Elo Rating, which gives us a standardized number (like 1200 or 1500) representing model quality.

Step 3: Fixing the Cost with SWIM

The downside of a Round-Robin tournament is cost. Comparing \(N\) models requires \(O(N^2)\) comparisons. If you have 100 models, that’s incredibly expensive.

To solve this, the authors propose Swiss-Wise Iterative Matchmaking (SWIM).

Inspired by Swiss-system tournaments (common in Chess or Magic: The Gathering), SWIM works by:

- Initializes everyone with a rough score.

- Matches models against opponents with similar current scores.

- Updates scores based on results.

- Repeats.

Because models only fight opponents near their skill level, the system converges on the correct ranking much faster—approximately \(O(N \log N)\) complexity. This makes it feasible to rank large numbers of models without breaking the bank.

5. Experimental Results: Does it Work?

The ultimate test of an automated judge is how well it agrees with humans. The researchers compared their new ranking methods against the Chatbot Arena, a crowdsourced platform where thousands of humans vote on model outputs.

Correlation with Human Judgment

The results were definitive. The Round-Robin method (combined with the Bradley-Terry model) significantly outperformed the standard AlpacaEval win-rates.

Figure 5: Moving to Round-Robin + Bradley-Terry increases alignment with human rankings by over 13% in Spearman Correlation compared to standard AlpacaEval 2.0.

Figure 5: Moving to Round-Robin + Bradley-Terry increases alignment with human rankings by over 13% in Spearman Correlation compared to standard AlpacaEval 2.0.

SWIM vs. Round-Robin

Critically, the authors showed that the efficient SWIM algorithm achieves nearly the same accuracy as the expensive Round-Robin approach.

Figure 6: The green line (SWIM) tracks the blue line (Round-Robin) almost perfectly, consistently beating the standard AlpacaEval (red line).

Figure 6: The green line (SWIM) tracks the blue line (Round-Robin) almost perfectly, consistently beating the standard AlpacaEval (red line).

This confirms that we can have high-quality, transitive-aware rankings without the exhaustive computational cost of checking every single pair.

6. Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The widespread adoption of “LLM-as-a-Judge” has been a major unlock for AI development, but this paper serves as a crucial sanity check. We cannot blindly trust that AI judges are logical.

Key Takeaways for Students & Practitioners:

- Transitivity is a Myth: Do not assume that because Model A > B and B > C, that A > C. LLM preferences are noisy and cyclic.

- Baselines are Dangerous: Rankings based on a single fixed baseline (like GPT-4 Preview) are unstable. Changing the baseline changes the leaderboard.

- Math to the Rescue: Statistical methods like the Bradley-Terry model are essential for converting noisy pairwise data into robust rankings.

- Efficiency Matters: You don’t need to simulate every match. Smart matchmaking algorithms like SWIM allows for accurate ranking at a fraction of the compute cost.

As we move toward more autonomous AI agents, evaluating them accurately becomes a safety concern. By acknowledging and mitigating non-transitivity, we move one step closer to evaluation frameworks that we can actually trust.

The images and data discussed in this post are based on the paper “Investigating Non-Transitivity in LLM-as-a-Judge” (2025).

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.14074/images/cover.png)