Introduction: The Art of Learning

Imagine you are learning to play the guitar. You start by strumming a few basic chords—G, C, and D. After a week, you’ve mastered them. Now, if you want to become a virtuoso, what should you do? Should you spend the next year playing those same three chords over and over again? Or should you deliberately seek out difficult fingerpicking patterns, complex jazz scales, and songs that force you to stretch your fingers in uncomfortable ways?

The answer is obvious to any human: Deliberate Practice. Progress isn’t made by passively repeating what you already know; it is made by continuously engaging with tasks that sit right at the edge of your current abilities.

In the world of Artificial Intelligence, however, we often forget this principle. When we train deep learning models—specifically when using synthetic data generated by other AI models—we tend to generate a massive, static dataset upfront. We feed this data to the student model, hoping it learns. But just like the guitarist playing the same chords, the model quickly hits a point of diminishing returns. Adding more “easy” data stops improving performance.

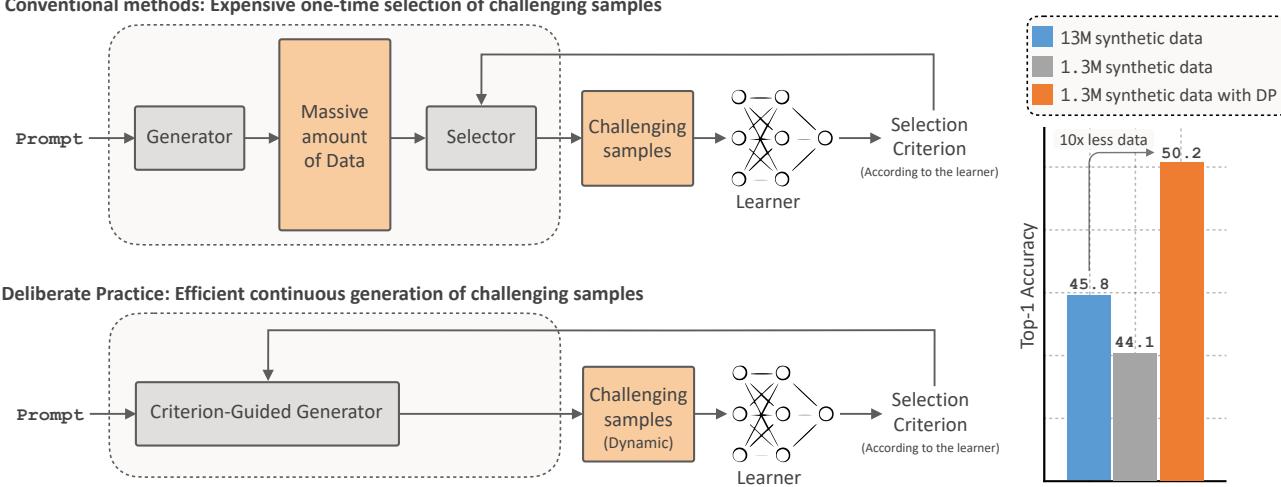

In this post, we are diving deep into a fascinating paper titled “Improving the Scaling Laws of Synthetic Data with Deliberate Practice.” The researchers propose a dynamic framework where the generative model (the teacher) and the classifier (the student) interact in a continuous loop. Instead of generating random data, the teacher generates specific examples that the student currently finds confusing.

This simple shift in philosophy leads to massive efficiency gains: achieving better accuracy with 3.4x to 8x less data than traditional methods.

The Problem: The Synthetic Data Plateau

We are living in an era where real-world labeled data is becoming a bottleneck. It is expensive to collect, raises privacy concerns, and is finite. Naturally, researchers have turned to text-to-image (T2I) generative models (like Stable Diffusion) to create infinite synthetic datasets.

The theory is seductive: if we have a model that can generate any image, surely we can train a classifier solely on synthetic data to recognize anything?

However, empirical studies have revealed a harsh reality: scaling synthetic data follows a power law of diminishing returns. You can double your dataset size, but your accuracy gains will shrink rapidly. This happens because generative models, by default, tend to produce “prototypical” examples—standard, easy-to-recognize images (e.g., a Golden Retriever sitting on a lawn). Once the classifier learns what a standard Golden Retriever looks like, seeing a million more of them offers zero educational value.

The Inefficiency of “Generate then Prune”

To fix this, prior works attempted to use pruning. The workflow looks like this:

- Generate a massive pool of random synthetic images (e.g., 10 million images).

- Use a metric (like prediction entropy) to identify the “hard” or informative ones.

- Throw away 90% of the data and train on the remaining top 10%.

While this works better than random training, it is computationally wasteful. You are spending GPU cycles generating millions of images just to delete them.

This paper asks a fundamental question: Instead of generating trash and throwing it away, can we mathematically force the generator to produce only the “hard” examples in the first place?

The Solution: Deliberate Practice (DP)

The researchers introduce a framework called Deliberate Practice (DP). It transforms the training pipeline from a straight line into a dynamic loop.

The process operates on a Patience Mechanism:

- Initial Training: Start with a small, random synthetic dataset. Train the classifier until its validation accuracy plateaus (it stops learning).

- Feedback: Once the learner is stuck, use its current state to calculate entropy (uncertainty).

- Targeted Generation: Use this entropy to guide the diffusion model. Force it to generate new images that maximize the learner’s confusion.

- Loop: Add these new, difficult examples to the dataset and resume training. Repeat.

This mirrors human learning. You practice until you plateau, you identify your weakness, you practice that specific weakness, and you improve.

The Math: Entropy-Guided Sampling

How do we tell a diffusion model to “generate something confusing”? We have to modify the mathematics of the generation process.

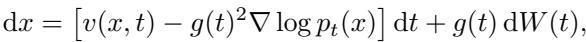

Standard diffusion models generate data by solving a reverse Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE). We usually sample from a distribution \(P\). However, we want to sample from a target distribution \(Q\), which emphasizes informative samples.

Here, \(\pi\) is a weighting function that prioritizes informative samples.

In a standard diffusion process, the reverse SDE looks like this:

To sample from the informative distribution \(Q\) instead of \(P\), we apply Girsanov’s Theorem. This theorem tells us that shifting the probability measure introduces a “correction” term to the drift of the SDE.

Notice the new term: \(\nabla \log \pi(x, t)\). This is the gradient of our weighting function. It acts as a steering wheel, pushing the generation process toward high-value regions of the latent space.

The Guide: Classifier Entropy

The authors define the weighting function \(\pi\) based on the Shannon Entropy (\(H\)) of the classifier (\(f_\phi\)). High entropy means the classifier is unsure about the class of the image (e.g., is it a cat or a dog?).

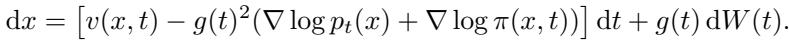

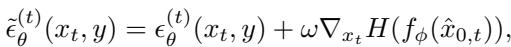

To implement this efficiently, they use Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM). During the generation of an image, at each timestep \(t\), the model has a noisy version of the image \(x_t\). The authors approximate the final clean image \(\hat{x}_{0,t}\) and feed it into the classifier to check the entropy.

They then compute the gradient of this entropy with respect to the noisy image and add it to the noise prediction \(\epsilon_\theta\). This steers the denoising process.

In this equation:

- \(\epsilon_\theta^{(t)}\) is the standard diffusion noise prediction.

- \(\omega\) is a hyperparameter controlling how much we want to force “hardness.”

- \(\nabla_{x_t} H\) is the direction that increases the classifier’s confusion.

By setting \(\omega > 0\), the generator is no longer producing “average” images. It is actively trying to produce images that exist on the decision boundaries of the current classifier.

Theoretical Analysis: Why “Hard” Data Scales Better

Before looking at the ImageNet results, it is crucial to understand why this works mathematically. The authors provide a rigorous analysis using Random Matrix Theory (RMT) to model the scaling laws of synthetic data.

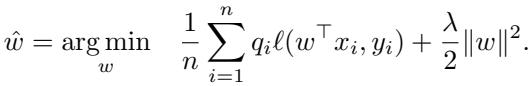

They set up a simplified theoretical environment: a linear classifier trained on high-dimensional data, where they can control exactly which data points are selected for training.

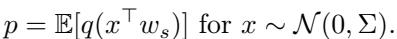

They model the test error as a function of the dataset size (\(n\)) and the input dimension (\(d\)). Specifically, they analyze the pruning ratio \(p\)—the probability of keeping a sample.

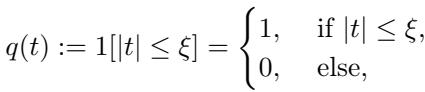

The selection strategy \(q(t)\) determines which samples are kept. A “Keep Hard” strategy only selects samples close to the decision boundary (where \(|t| \leq \xi\)).

The Scaling Law Breakthrough

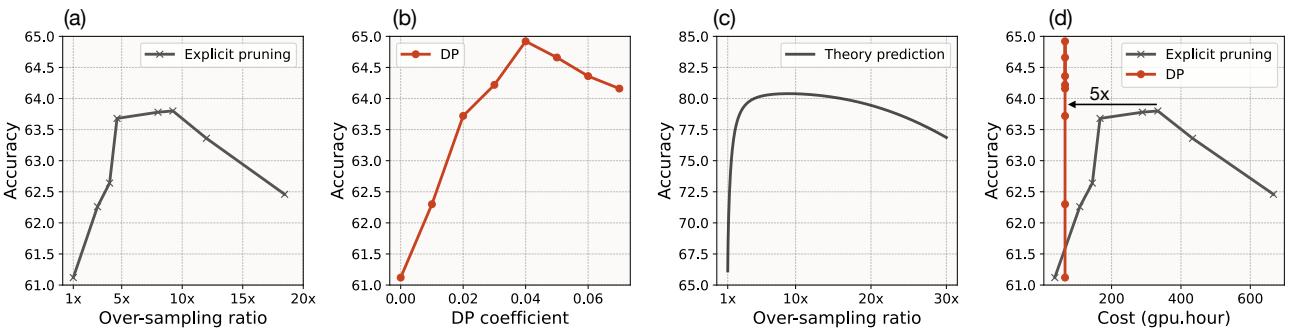

Using this theoretical framework, the authors derived the asymptotic test error for different selection strategies. The visual result of this theory is striking:

Look at the graph above.

- The Black/Gray lines represent random selection (standard training). The curve flattens out; you need exponentially more data to lower the error.

- The Red line represents selecting the top 10% hardest examples. It starts with higher error (because the dataset is tiny), but as you add data, it surpasses the random strategy and scales much faster.

The theory predicts that training on a smaller, harder dataset is not just “as good” as training on a large random one—it fundamentally changes the scaling exponent. You get more “intelligence” per bits of data.

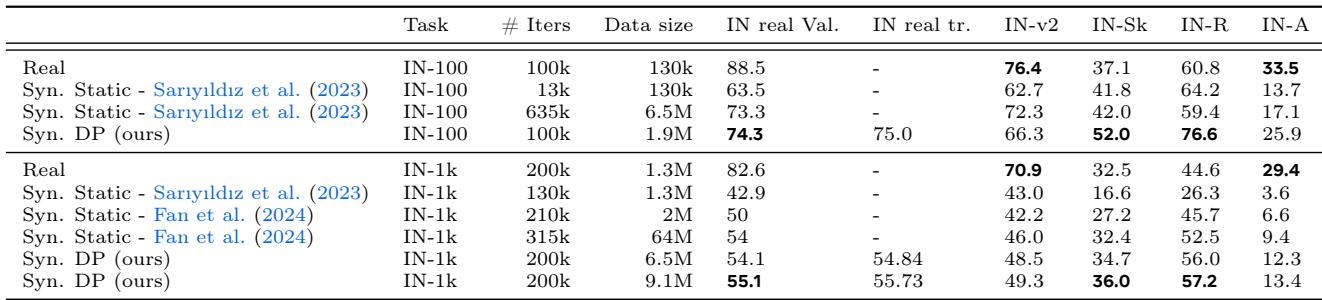

Experimental Results: Smashing the Baselines

The authors validated their framework on ImageNet-100 and ImageNet-1k, training solely on synthetic data generated by Stable Diffusion (LDM-1.5), and testing on real-world validation data.

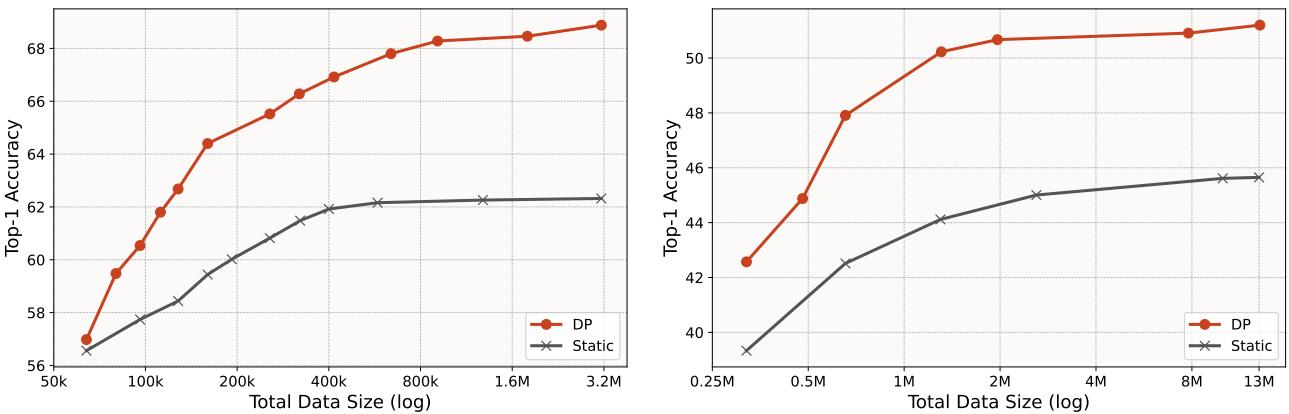

1. Scaling Performance

The comparison between Static generation (standard) and Deliberate Practice (DP) is stark.

- ImageNet-100 (Left): DP achieves the same accuracy as the static setup using 7.5x less data.

- ImageNet-1k (Right): DP outperforms the best static accuracy (trained on 13M images) using only ~640k images. That is a 20x reduction in data for comparable performance.

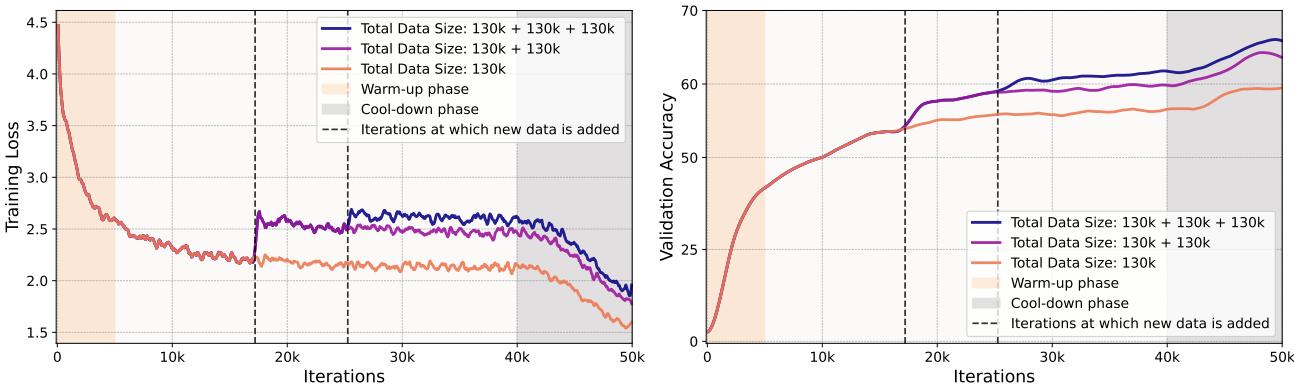

2. Training Dynamics

One of the most interesting findings is how the training metrics behave. Usually, we want training loss to go down. But in Deliberate Practice, we keep injecting “hard” data, which spikes the loss.

In the figure above, the vertical dashed lines represent the moments where the classifier plateaued, and the generator injected a new batch of entropy-optimized data.

- Left Graph: The training loss increases at the dashed lines. This confirms the new data is indeed difficult for the model.

- Right Graph: Despite the higher training loss, the validation accuracy (on real data) jumps up. This is the definition of effective learning—struggling with difficult concepts leads to better generalization.

3. Computational Efficiency

A major critique of “hard mining” strategies is the cost. If you have to generate 100 images to find 1 good one, aren’t you wasting compute?

The authors compared DP (direct generation) against “Explicit Pruning” (generate many, select few).

Look at Panel (d) in the image above.

- The DP method (Orange) achieves high accuracy with significantly fewer GPU hours compared to Explicit Pruning (Blue).

- Generating a single image with entropy guidance takes about 1.8x longer than a standard generation, but because you need to generate far fewer images total, the overall compute cost is 5x lower.

The difference in workflow is visualized beautifully here:

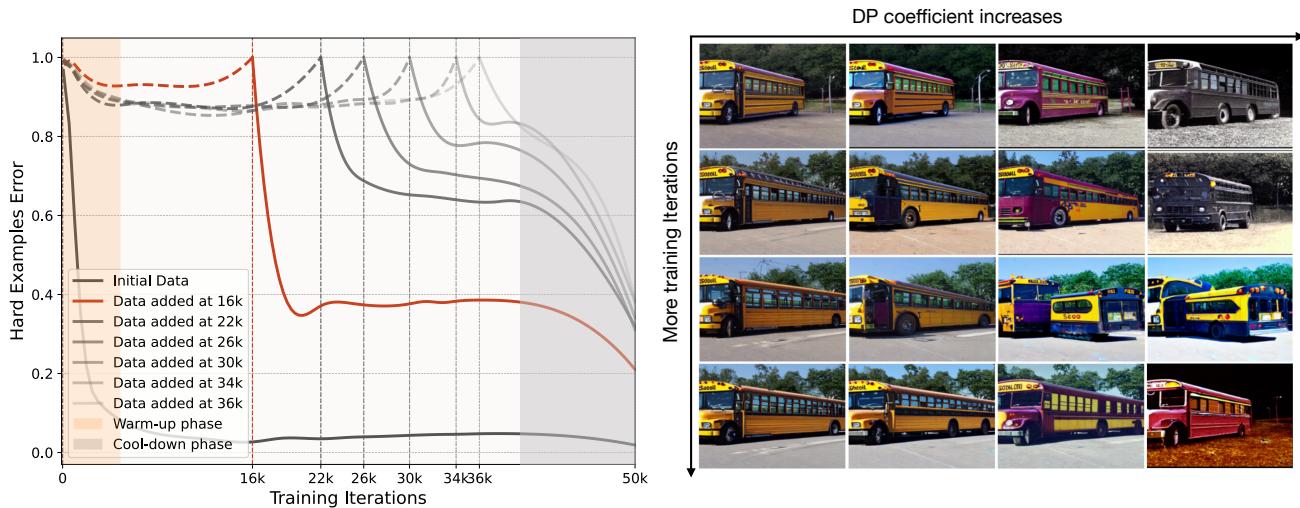

Visualizing the Learning Process

What does a “hard” example look like? And does “hardness” change over time?

The authors tracked the error rates of specific batches of data. They found that examples that were “hard” at iteration 10,000 became “easy” by iteration 30,000. This confirms that static datasets are suboptimal because the definition of “informative” is a moving target.

We can also see the evolution of the generated images. In the early stages of training, the model might be confused by simple color variations. Later, it understands color but gets confused by complex shapes or viewpoints. The generator adapts to this.

In the example below for the class “School Bus,” early generations (top) might focus on basic yellow blobs. As the model learns, the generator (with high entropy guidance \(\omega\)) starts producing weird angles, distorted shapes, or unusual contexts to challenge the learner.

Similarly, for the “Fox” class, the initial data (top) looks somewhat uniform. By the end of training (bottom), the accumulated dataset contains a diverse array of poses, lighting conditions, and backgrounds.

Conclusion: The Future of Synthetic Data

The paper “Improving the Scaling Laws of Synthetic Data with Deliberate Practice” offers a pivotal shift in how we approach AI training. It moves us away from the brute-force mentality of “more data is better” toward a more nuanced, pedagogical approach: “better data is better.”

By creating a feedback loop between the student (classifier) and the teacher (generator), we can:

- Break the Scaling Plateau: Continue improving accuracy long after random sampling saturates.

- Save Compute: Train better models with massive reductions in dataset size (up to 8x) and training iterations.

- Dynamic Adaptation: Ensure the data evolves alongside the model’s capability.

Table 1 summarizes the dominance of this method against previous state-of-the-art synthetic training methods:

This research suggests that the future of training large models might not lie in simply scraping more of the internet, but in synthesizing highly targeted, intelligent curriculums that adapt to the model in real-time. Just as a music teacher guides a student through increasingly difficult pieces, our generative models can guide our classifiers toward robustness and high performance.

This blog post explains the research presented in “Improving the Scaling Laws of Synthetic Data with Deliberate Practice” by Askari-Hemmat et al. (Meta FAIR, 2025).

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.15588/images/cover.png)