Introduction

We often think of Large Language Models (LLMs) as vast repositories of static knowledge—encyclopedias that can talk. You ask a question, and they predict the next likely token based on the massive datasets they were trained on. But as we move from building chatbots to building agents—systems capable of achieving goals independently—this passive nature becomes a bottleneck.

A true agent doesn’t just answer; it investigates. It interacts with the world. If you ask an agent to “diagnose why the server is down,” it shouldn’t just guess based on its training data; it needs to log in, check metrics, read error logs, and strategically gather information until it finds the root cause. This requires exploration.

The problem is that existing LLMs are often poor at this specific type of strategic information gathering. They tend to hallucinate answers rather than ask clarifying questions, or they explore inefficiently, wasting steps on irrelevant actions. Furthermore, training them to do this in the real world is dangerous and expensive—you don’t want an AI randomly deleting files on a server just to “see what happens.”

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into PAPRIKA, a research paper that proposes a novel method for training generally curious agents. The researchers introduce a way to teach LLMs how to perform “in-context Reinforcement Learning (RL).” By fine-tuning models on a diverse suite of synthetic decision-making tasks, they created agents that can not only solve the tasks they were trained on but can also generalize their exploration strategies to completely unseen games and scenarios.

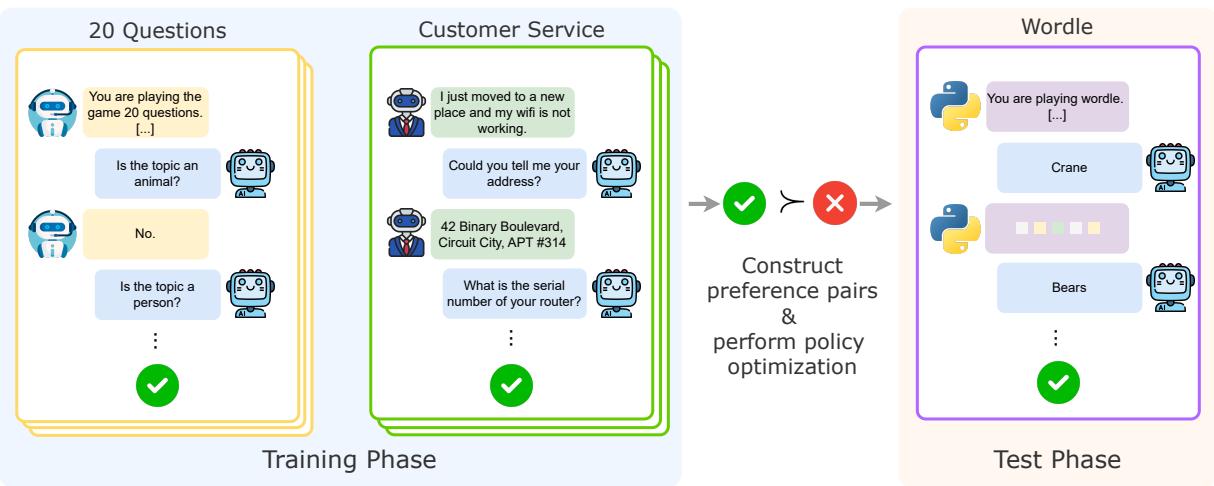

As illustrated in Figure 1, PAPRIKA shifts the focus from training a model on specific problems to training it on the general process of solving problems.

The Challenge of In-Context Exploration

To understand why this is difficult, we need to look at how LLMs are typically trained. Pre-training and standard Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) teach a model to mimic human responses. However, decision-making is a sequential process. An agent must take an action, observe the environment’s feedback, update its internal state, and plan the next move. This is a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP).

The authors identify two main hurdles:

- Data Scarcity: Most naturally occurring text data (like Wikipedia or Reddit) lacks the structure of interactive trial-and-error. It contains the results of decision-making, not the iterative process itself.

- Safety and Cost: Collecting interaction data by deploying untrained models into the real world leads to errors that can be costly or risky.

The PAPRIKA (which stands for a catchy acronym but is primarily inspired by the dream-detective movie Paprika) approach circumvents these issues by generating synthetic interaction data. If we can’t trust the model in the real world yet, we build it a digital playground.

The Methodology: Building a Curious Agent

The core method of the paper consists of three pillars: Task Design, Data Construction, and Optimization.

1. The Playground: Task Design

To teach an agent how to explore, you first need environments that require exploration. The researchers designed 10 diverse task groups. These aren’t just simple Q&A datasets; they are interactive environments where the agent must interact over multiple turns to succeed.

Crucially, these tasks are partially observable. The agent doesn’t know the answer at the start. It must perform actions (ask questions, make guesses, check grids) to uncover hidden information.

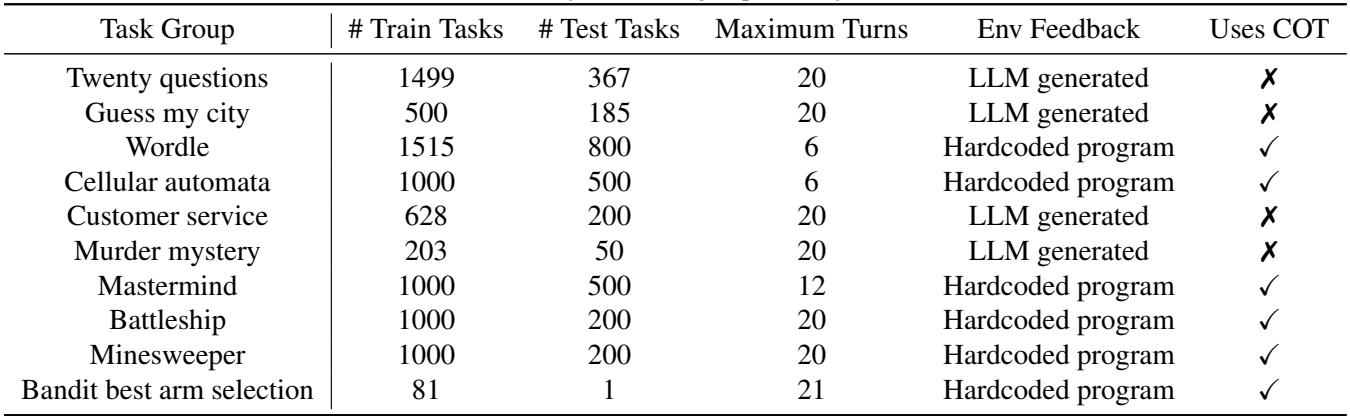

As shown in Table 1, the tasks range from linguistic games to logic puzzles:

- Twenty Questions & Guess My City: Pure information gathering. The agent must narrow down a vast search space efficiently.

- Wordle & Mastermind: Deductive reasoning where feedback allows the agent to eliminate possibilities.

- Battleship & Minesweeper: 2D grid exploration requiring a balance of covering new ground (exploration) and targeting specific areas (exploitation).

- Customer Service & Murder Mystery: Role-playing scenarios where the “environment” is another LLM acting as a customer or a game master.

The diversity here is key. If you only train an agent on “Twenty Questions,” it learns to ask “Is it an animal?” It doesn’t learn the abstract concept of binary search. By training on many different tasks, the goal is to force the model to learn the underlying logic of exploration.

2. Dataset Construction: Self-Play

How do we get training data for these tasks? We don’t have human experts play millions of games of Battleship. Instead, the authors use the LLM itself to generate data, a technique often called “bootstrapping.”

They take a base model (like Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct) and have it play these games. To ensure the model tries different strategies, they use Min-p sampling with a high temperature. This randomness encourages the model to explore diverse trajectories.

For every task, they generate multiple attempts. Some will fail, and some will succeed. They then create preference pairs \((h^w, h^l)\):

- Winner (\(h^w\)): The trajectory that solved the task in the fewest turns.

- Loser (\(h^l\)): A trajectory that failed or took significantly longer.

This creates a dataset that essentially says, “In this situation, this sequence of actions was better than that one.”

3. Optimization: SFT and DPO

Once the data is collected, the training occurs in two stages.

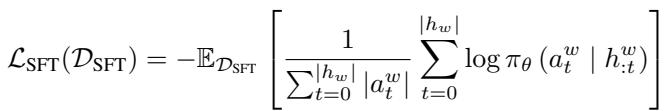

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

First, the model is fine-tuned on the winning trajectories. This is akin to behavioral cloning—teaching the model to imitate the successful strategies it discovered during the data generation phase.

The objective function (Equation 1) maximizes the likelihood of the actions taken in the winning trajectory \(h^w\).

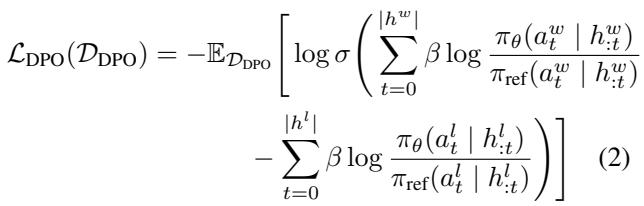

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)

SFT is good, but it doesn’t explicitly teach the model what not to do. Reinforcement Learning is usually better for this, but traditional RL (like PPO) is computationally expensive and unstable.

The authors use a sequential variant of Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). DPO allows the model to align with preferences (winning > losing) without needing a separate reward model.

Equation 2 shows the multi-turn DPO loss. It increases the probability of the winning actions while simultaneously decreasing the probability of the losing actions, relative to a reference model.

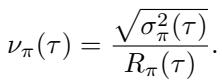

To stabilize training, they actually combine these two approaches into Robust Preference Optimization (RPO):

By adding the SFT loss back into the DPO objective (Equation 3), they prevent the model from drifting too far or “unlearning” the basic syntax of interaction, a common issue known as unintentional unalignment.

Scalability through Curriculum Learning

One of the most interesting contributions of this paper is how they handle the cost of training. In standard LLM training, the bottleneck is the gradient updates (the backward pass). In PAPRIKA, the bottleneck is sampling. Running thousands of episodes of “Murder Mystery” to generate training data takes a lot of inference time.

Furthermore, not all tasks are equally useful at all times. If a task is too hard, the model never wins, so you get no positive signal. If it’s too easy, the model learns nothing new.

To solve this, the authors propose a Curriculum Learning strategy based on the “learning potential” of a task. They define a metric called the coefficient of variation (\(\nu\)):

The intuition here is elegant:

- \(R_{\pi}(\tau)\) is the average reward (performance).

- \(\sigma_{\pi}^2(\tau)\) is the variance of that performance.

- If variance is high relative to the mean, the model is inconsistent. It can solve the task, but often fails. This is the “Goldilocks zone” where the model has the most to learn.

They treat task selection as a Multi-Armed Bandit problem. They use the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm to dynamically select which tasks to sample data from, prioritizing those with the highest estimated learning potential (\(\nu\)).

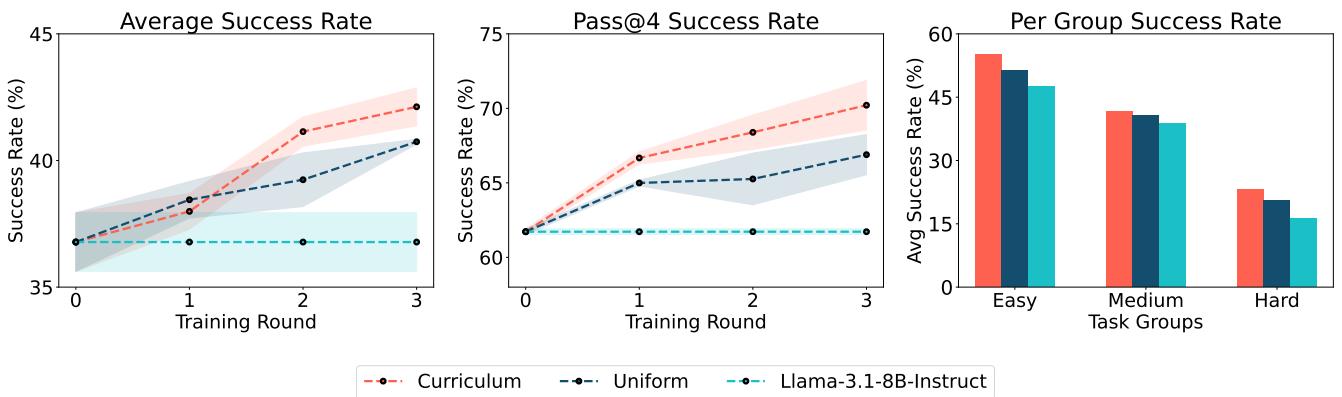

Figure 4 demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. The curriculum strategy (red line) consistently outperforms uniform sampling (blue line), achieving higher success rates faster. This proves that smart data selection is just as important as the training algorithm itself.

Experiments and Results

So, does training an agent on Minesweeper and Wordle actually make it smarter?

1. Improvement on Training Tasks

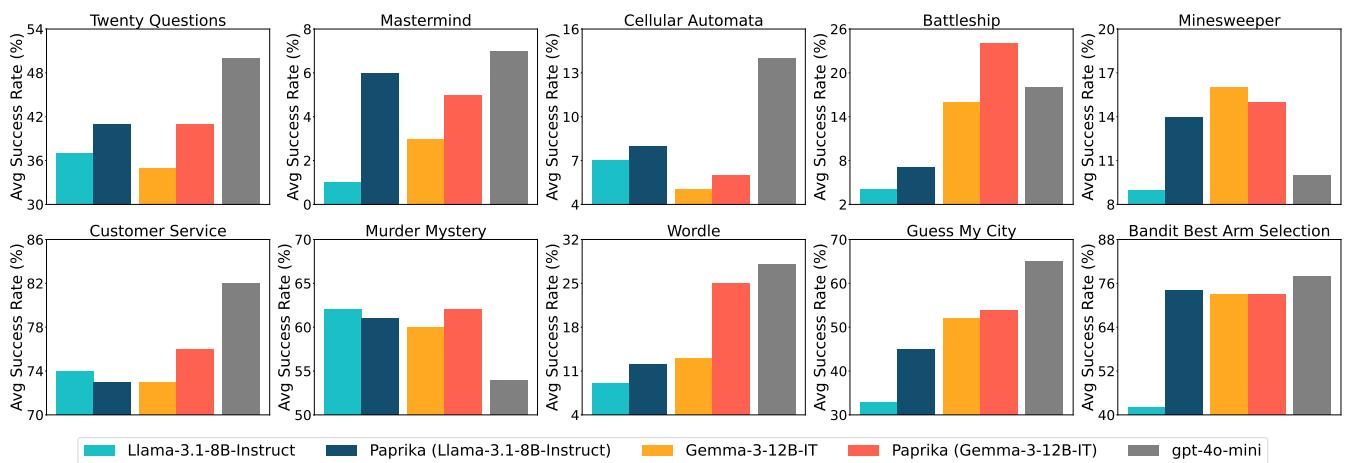

First, the basics. The researchers fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Gemma-3-12B-IT using PAPRIKA.

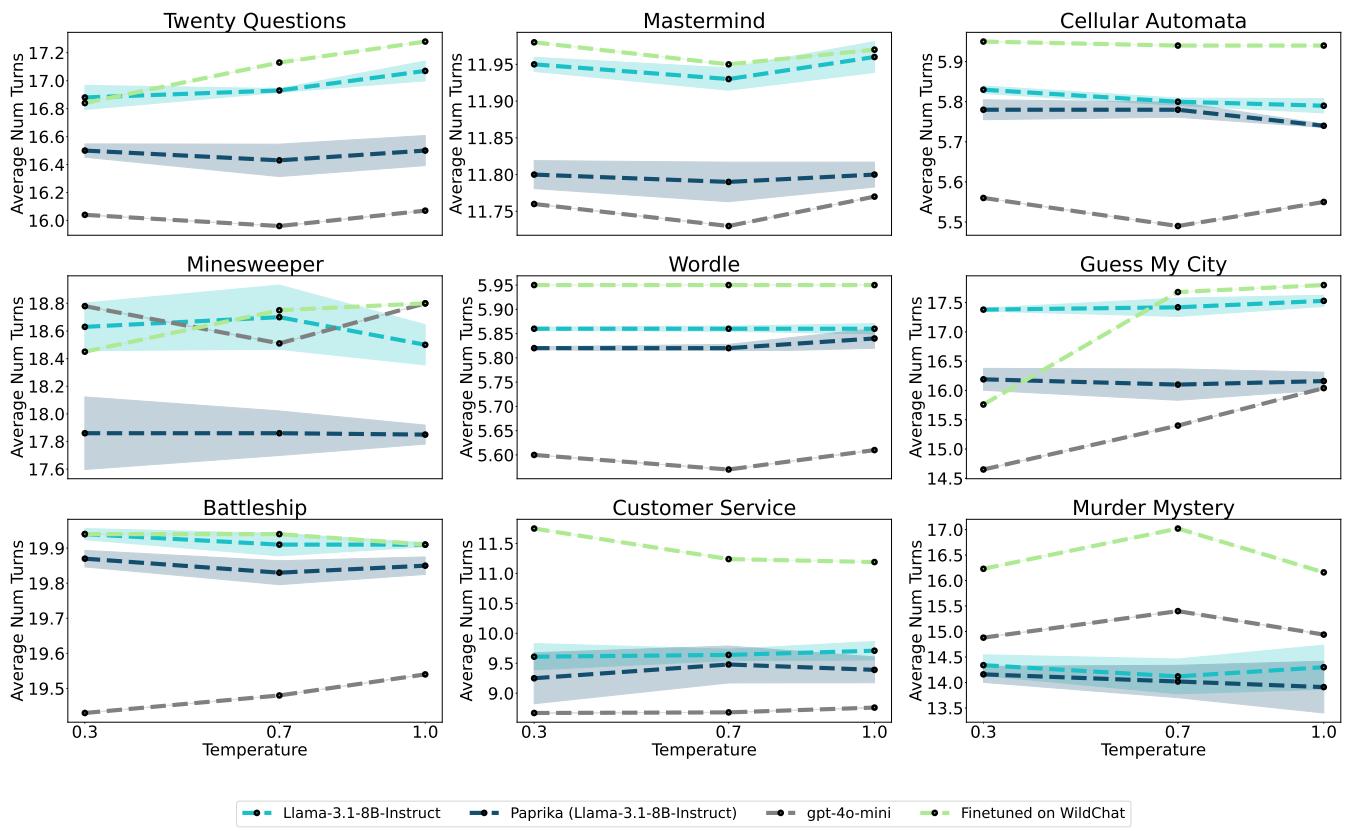

Figure 2 shows the results across all 10 task groups. The dark blue bars (PAPRIKA) consistently outperform the base Llama model (teal) and often rival the much larger GPT-4o-mini (gray). In “Guess My City” and “Wordle,” the improvement is massive.

They also found that the agents became more efficient.

Figure 7 shows that PAPRIKA (dark blue) requires fewer turns to solve tasks compared to the base model. This indicates the model isn’t just getting lucky; it’s asking better, more strategic questions to prune the search space quickly.

2. The Holy Grail: Zero-Shot Generalization

The most critical question in this research was: Does this transfer? If we train an agent on “Twenty Questions,” does it become better at “Battleship”?

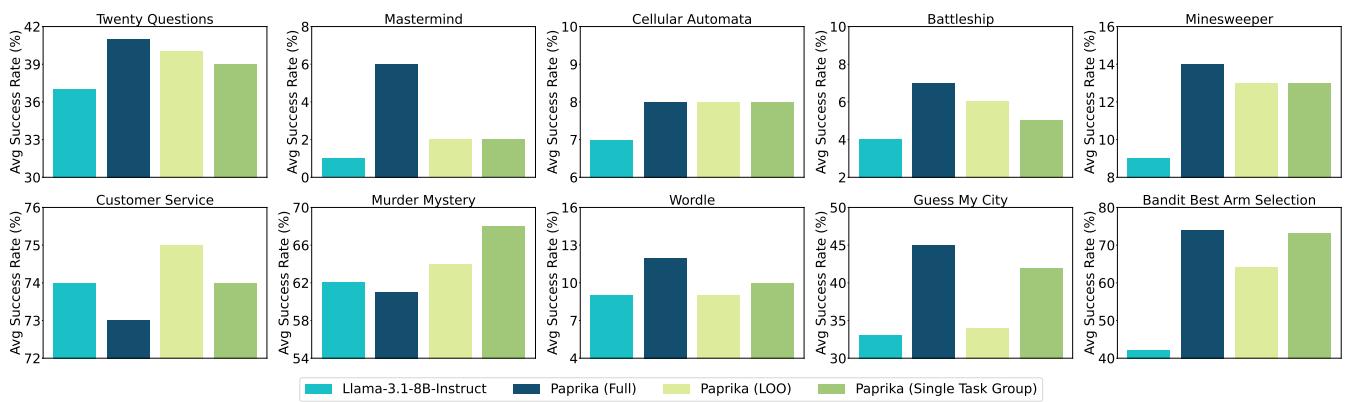

To test this, they performed Leave-One-Out (LOO) experiments. They trained the model on 9 task groups and tested it on the 10th unseen group.

Figure 3 presents these generalization results.

- PAPRIKA (LOO) (light green) refers to a model that has never seen the test task during training.

- Remarkably, the LOO model significantly outperforms the base Llama model on almost every task.

- In some cases (like “Twenty Questions”), the model trained on other tasks performed almost as well as the model trained on that specific task.

This suggests that PAPRIKA is teaching the model a generalizable skill—strategic inquiry—rather than just memorizing the rules of a specific game.

3. Does it break the model?

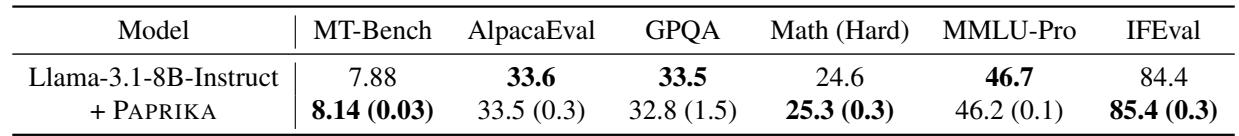

A common fear with fine-tuning on specialized data (like games) is “catastrophic forgetting,” where the model loses its general abilities (like writing code or answering history questions).

Table 2 shows evaluations on standard benchmarks like MT-Bench and MMLU. The PAPRIKA model shows no significant degradation. In fact, it slightly improves on reasoning-heavy benchmarks like GPQA and Math, suggesting that learning to explore might help with general reasoning as well.

Qualitative Analysis: A Look at the Behavior

Statistics are great, but what does a “curious” agent actually sound like?

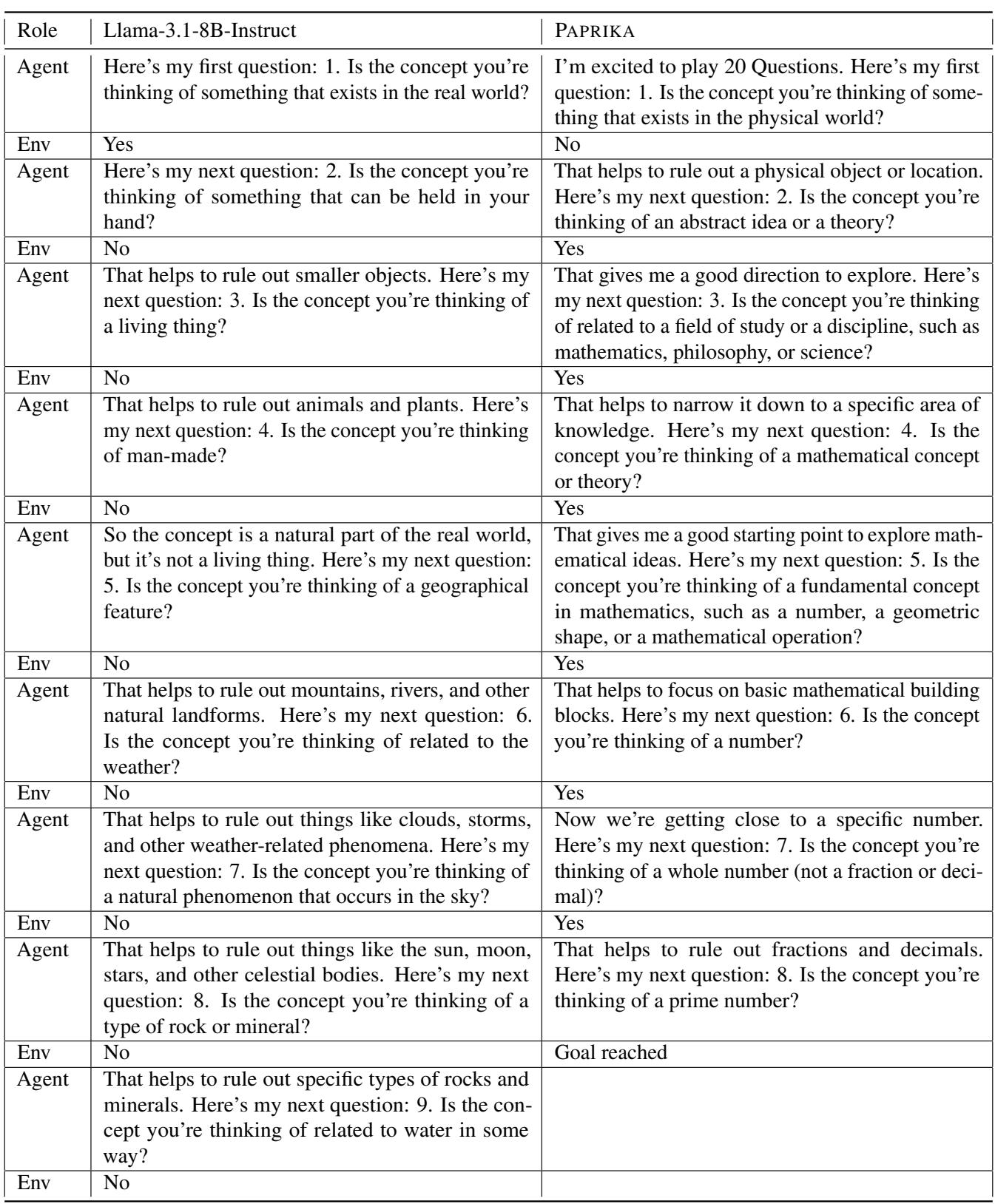

Let’s look at an example from the “Twenty Questions” task where the concept to guess is “Prime Numbers.”

Table 7 highlights the difference:

- Llama-3.1 (Base): Asks vague, redundant questions. It asks if it’s a “real world” object, then if it’s “man-made,” then if it’s a “geographical feature.” It’s flailing. It fails to identify the topic.

- PAPRIKA: Immediately categorizes the domain (“abstract idea”). It narrows it down to a field of study (“mathematics”), then a specific type (“number”), then a property (“prime”).

The PAPRIKA agent demonstrates binary search behavior in natural language. It understands that to find the answer, it must bisect the space of possibilities with every question.

Conclusion

The PAPRIKA framework represents a significant step forward in building autonomous agents. By treating exploration as a learnable, transferable skill, the authors showed that we don’t need to train agents on every possible scenario they might encounter.

Instead, by creating a “gym” of diverse, synthetic reasoning tasks and using preference optimization, we can instill a general capability for strategic information gathering.

Key Takeaways:

- Synthetic Data Works: You can boost reasoning capabilities using data generated by the model itself, provided you filter for high-quality trajectories.

- Exploration is Generalizable: Learning to play Wordle helps you play Battleship. The underlying logic of hypothesis testing and state elimination transfers across domains.

- Curriculum Matters: Using simple statistics (variance vs. mean) to prioritize training tasks can drastically improve sample efficiency.

As we move toward agents that book our flights, debug our code, and conduct scientific research, this ability to “ask the right question” will be the differentiator between a chatbot and a true intelligent assistant. PAPRIKA suggests that the path to get there might just be playing a lot of games.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.17543/images/cover.png)