Introduction

In the current landscape of AI image generation, we are witnessing a dominance of likelihood-based models. Whether it is Diffusion models (like Stable Diffusion or EDM) or Autoregressive models (like VAR), these architectures have set the standard for stability and scalability. They are the engines behind the “AI Art” revolution.

However, there is a catch. These models are typically trained using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). While MLE is fantastic for ensuring the model covers the entire distribution of the data, it has a well-known flaw: mode-covering. In simple terms, to avoid assigning zero probability to any real data point, MLE-trained models tend to “hedge their bets,” spreading their probability mass too thin. The visual result? Generated images can often look blurry or lack the high-frequency details that make a photo look truly “real.”

To fix this, researchers and engineers often rely on inference-time tricks like Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG) to force the model toward sharper results, often at the cost of diversity or inference speed.

But what if we could get the sharpness of a GAN (Generative Adversarial Network) without the instability of GAN training? What if we didn’t need a separate discriminator network at all?

This is the premise of Direct Discriminative Optimization (DDO).

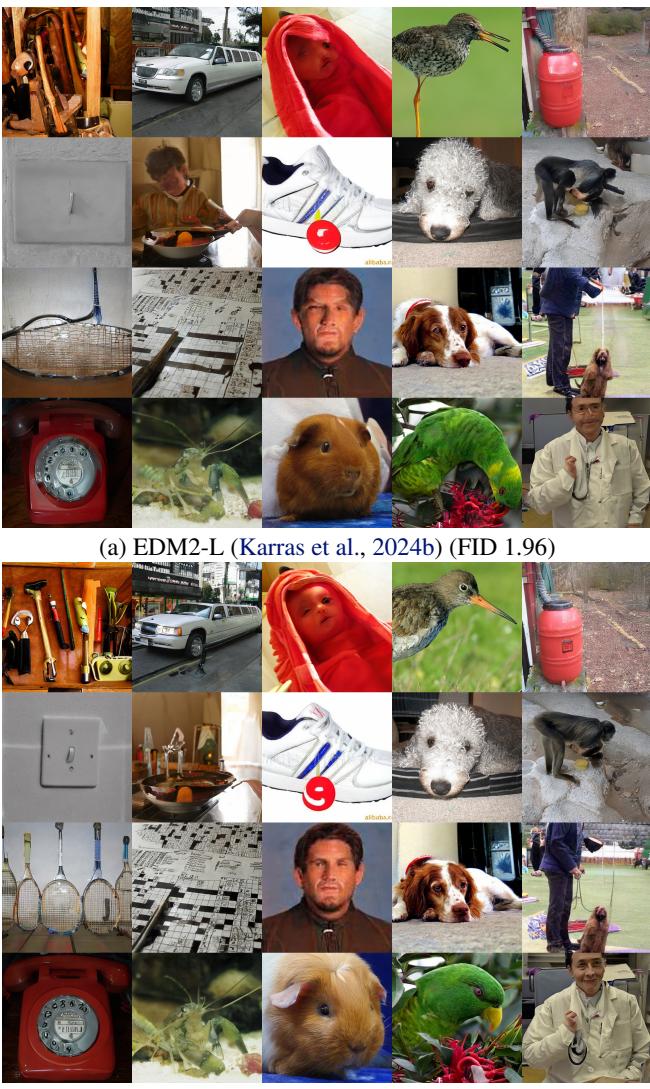

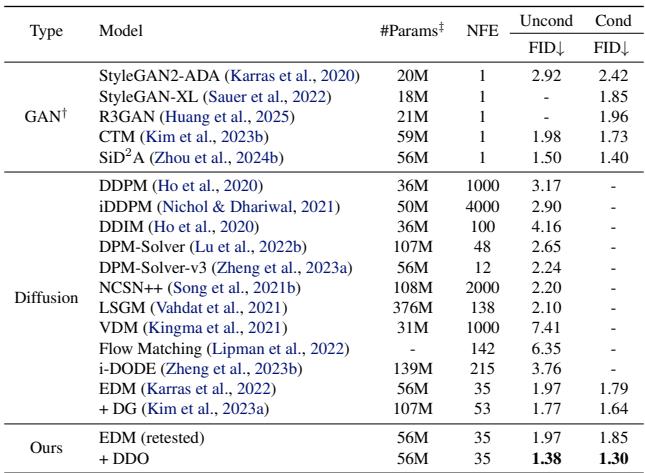

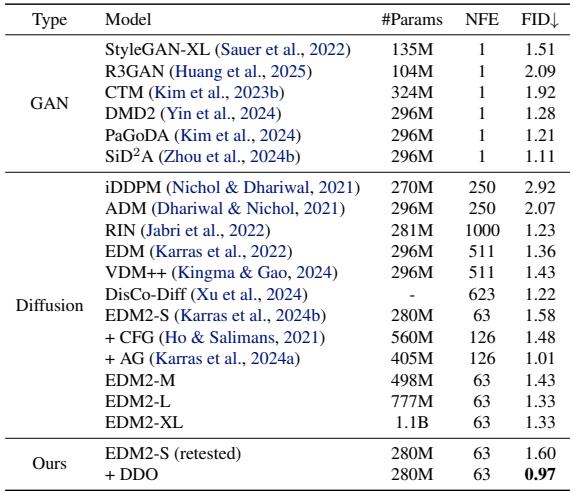

As shown above, DDO pushes state-of-the-art models (like EDM2) to new heights—achieving record-breaking FID scores without relying on heavy guidance. In this post, we will decode how DDO works, why your generative model is “secretly” a discriminator, and how this method bridges the gap between Diffusion and GANs.

Background: The Battle of Objectives

To understand why DDO is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of current training paradigms.

The Flaw in Maximum Likelihood

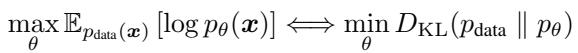

Likelihood-based generative models aim to minimize the difference between the data distribution (\(p_{data}\)) and the model distribution (\(p_{\theta}\)). Mathematically, this is equivalent to minimizing the forward Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence.

The issue with Forward KL is that it imposes a heavy penalty if the model ignores any part of the real data distribution. If the model has limited capacity (which all models do), it compromises by spreading out its density to cover everything.

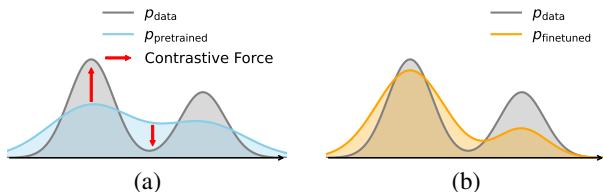

As illustrated in Figure 2(a) above, the pretrained model (blue curve) is wider and flatter than the true data (gray curve). It covers the data, but it doesn’t peak where the data peaks. This results in the generation of “average” or blurry samples.

The GAN Alternative

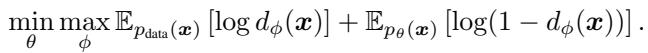

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) take a different approach. They don’t just maximize likelihood; they play a game. A generator tries to create images, and a separate discriminator network tries to tell if they are real or fake.

The GAN objective (often related to Jensen-Shannon divergence or Reverse KL) encourages mode-seeking. The model is rewarded for producing samples that live squarely on the data manifold, resulting in high fidelity. However, GANs are notoriously unstable to train because you have to balance two distinct networks fighting against each other.

Core Method: Direct Discriminative Optimization

The researchers propose a method that combines the stability of likelihood models with the sharpness of GANs. The core insight is fascinatingly simple: You don’t need a separate discriminator network.

The Hidden Discriminator

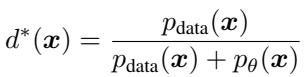

Let’s look at the optimal solution for a GAN discriminator. If we had a fixed generator (let’s call it a reference model, \(\theta_{ref}\)) and real data, the perfect discriminator \(d^*(x)\) is defined by the ratio of real data density to the generated density:

This equation tells us that if we know the probability densities, we know the optimal discriminator. Likelihood-based models (like Diffusion or Autoregressive models) are designed specifically to give us these densities (\(p_{\theta}\)).

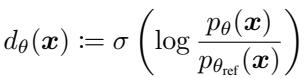

Therefore, instead of training a separate neural network to classify “real vs. fake,” we can parameterize the discriminator implicitly using the model itself. We compare our current trainable model (\(p_{\theta}\)) against a frozen version of itself from the previous training stage (\(p_{\theta_{ref}}\)).

By plugging this definition into the standard GAN loss, we get the DDO Objective:

How DDO Works in Practice

The DDO framework operates in a cycle that resembles “Self-Play.”

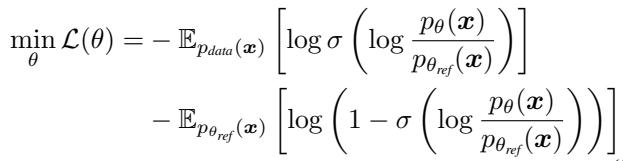

- Reference: You start with a pretrained model (e.g., a standard diffusion model). You freeze a copy of it to serve as the “Reference” (\(p_{\theta_{ref}}\)).

- Sampling: You generate “fake” samples using this frozen reference model.

- Optimization: You train the target model (\(p_{\theta}\)) to distinguish between the real data and the samples generated by the reference.

Because the discriminator is defined by the likelihood ratio, maximizing the discriminator’s success is mathematically equivalent to pushing the model distribution \(p_{\theta}\) toward the real data distribution \(p_{data}\).

As shown in the diagram above:

- Contrastive Force: The model is trained to increase the likelihood of real data (Positive signal).

- Negative Signal: Uniquely, the model is also trained to decrease the likelihood of samples generated by the reference model (Negative signal).

This usage of “negative signals” from self-generated data is what separates DDO from standard fine-tuning. It actively pushes the model away from the low-quality regions that the base model tends to generate.

Understanding the Gradients

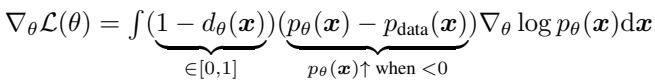

What is actually happening to the model weights during this process? If we analyze the gradient of the loss function, we see precisely how DDO improves the model:

The gradient has three components:

- Likelihood Gradient: \(\nabla \log p_{\theta}(x)\) — The standard direction to increase probability.

- Difference Term: \((p_{\theta}(x) - p_{data}(x))\) — The model pushes probabilities up if they are lower than the data distribution, and down if they are higher.

- Discriminator Weight: \((1 - d_{\theta}(x))\) — The update is weighted by how “fake” the sample looks.

This confirms that DDO is performing a specific kind of density correction, shifting probability mass from over-represented regions (blurry modes) to under-represented regions (sharp modes).

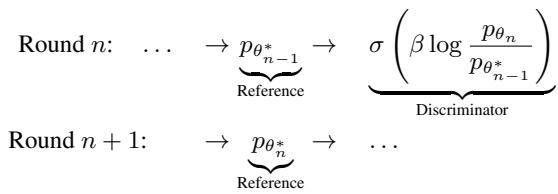

Iterative Refinement (Self-Play)

One round of DDO provides a significant boost, but since the reference model is fixed, the improvement eventually plateaus. To solve this, the authors employ an iterative strategy.

After Round 1 is finished, the optimized model becomes the new Reference for Round 2. This allows the model to continuously climb towards better quality, effectively “bootstrapping” its own improvements.

This is computationally efficient because each round is very short—typically requiring less than 1% of the original pre-training epochs.

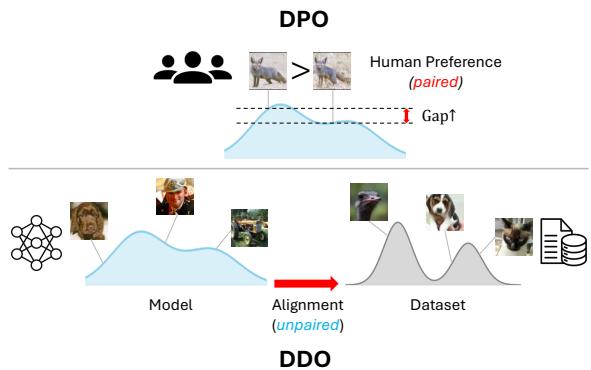

Connection to Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)

If you follow Large Language Model (LLM) research, this might sound familiar. DDO is inspired by Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), a technique used to align LLMs (like Llama or GPT) with human preferences without a complex Reinforcement Learning setup.

However, there is a key difference. DPO relies on paired preference data (Outcome A vs. Outcome B, where a human prefers A). DDO works on unpaired distributions (Real Data vs. Generated Data).

DDO adapts the mathematical elegance of DPO to the domain of visual generation, replacing “human preference” with “ground truth data distribution.”

Experiments and Results

The authors tested DDO on two major classes of generative models: Diffusion Models (EDM, EDM2) and Autoregressive Models (VAR).

Diffusion Models (CIFAR-10 & ImageNet)

The results on standard benchmarks were impressive. On CIFAR-10, DDO improved the FID (Fréchet Inception Distance, where lower is better) of the state-of-the-art EDM model significantly.

Perhaps most notably, DDO achieved these results without guidance. Usually, to get very low FID scores, diffusion models rely on Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG), which doubles the inference cost (because you have to run the model twice per step). DDO effectively “bakes” this quality into the weights.

On ImageNet-64 and ImageNet-512, the trend continued. The method established new state-of-the-art records for guidance-free generation.

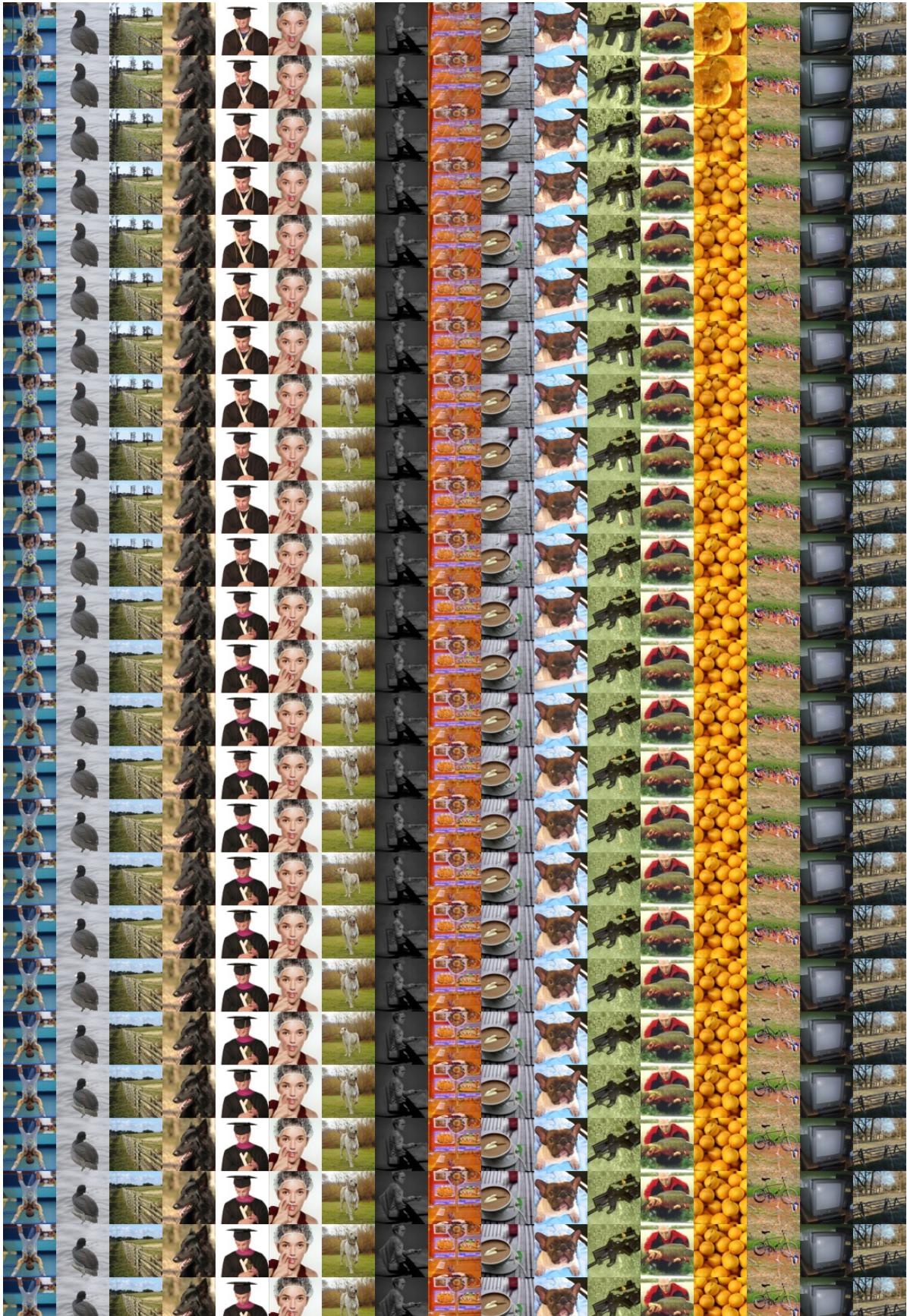

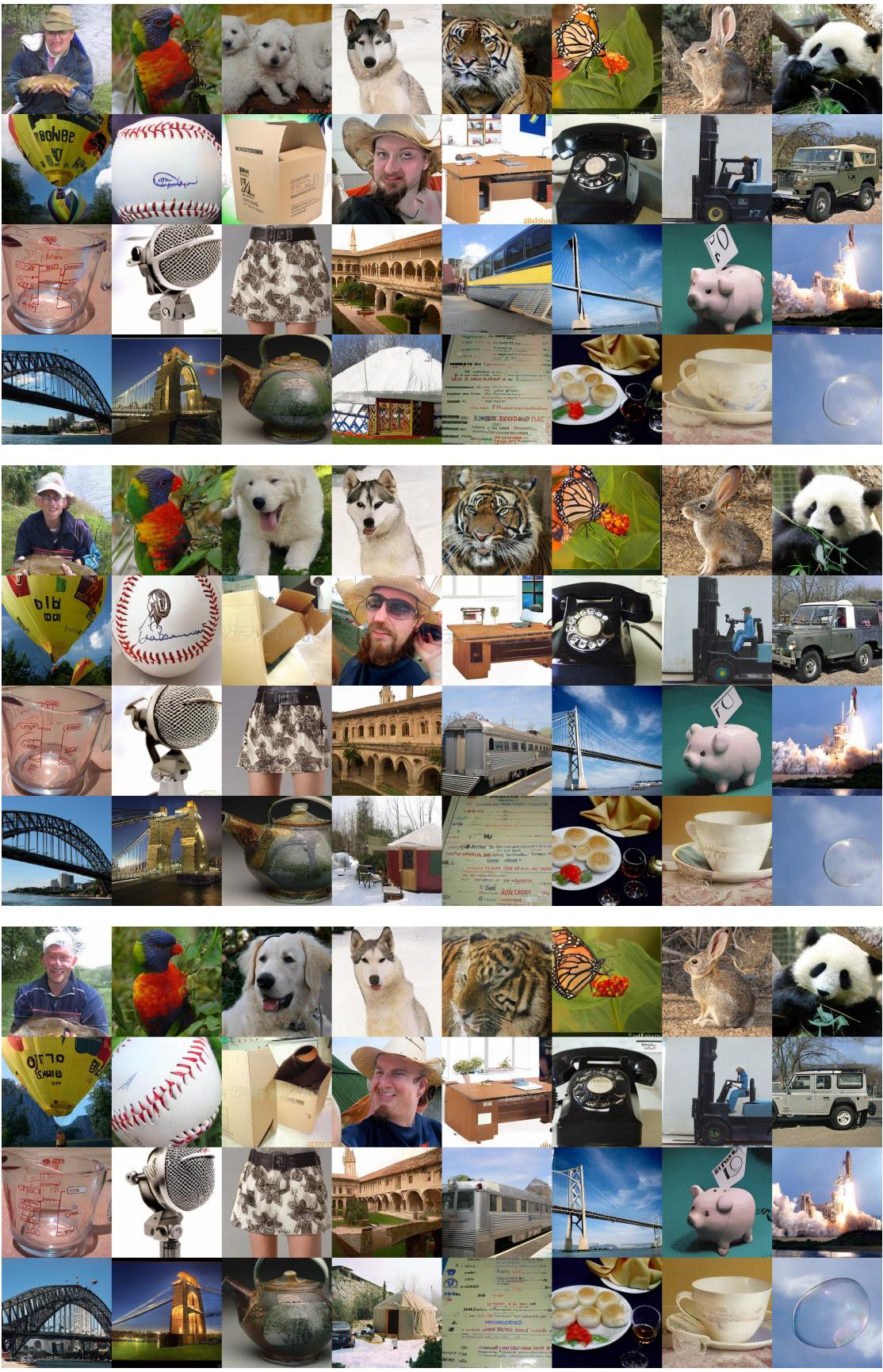

The visual progression of samples during the multi-round refinement process clearly shows the model resolving details and fixing artifacts over time.

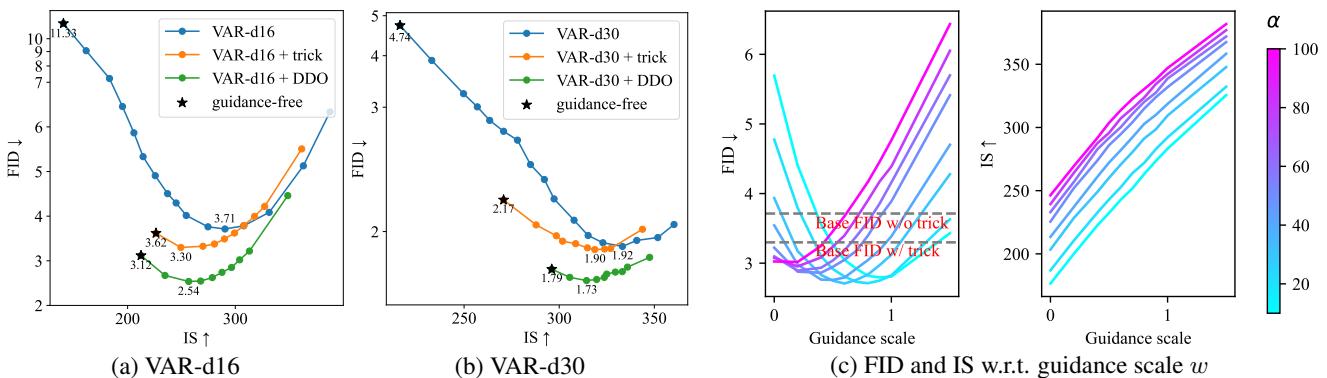

Autoregressive Models (VAR)

Autoregressive models usually require heavy CFG to produce coherent images. The authors applied DDO to the VAR (Visual Autoregressive) model.

The chart below shows the trade-off between FID (Quality) and IS (Inception Score/Diversity). The DDO-finetuned models (Green line) consistently outperform the base models, achieving better quality at every level of guidance.

Crucially, DDO allowed the VAR model to generate high-quality images without any “sampling tricks” (like top-k or top-p sampling), which typically reduce diversity to hide model flaws.

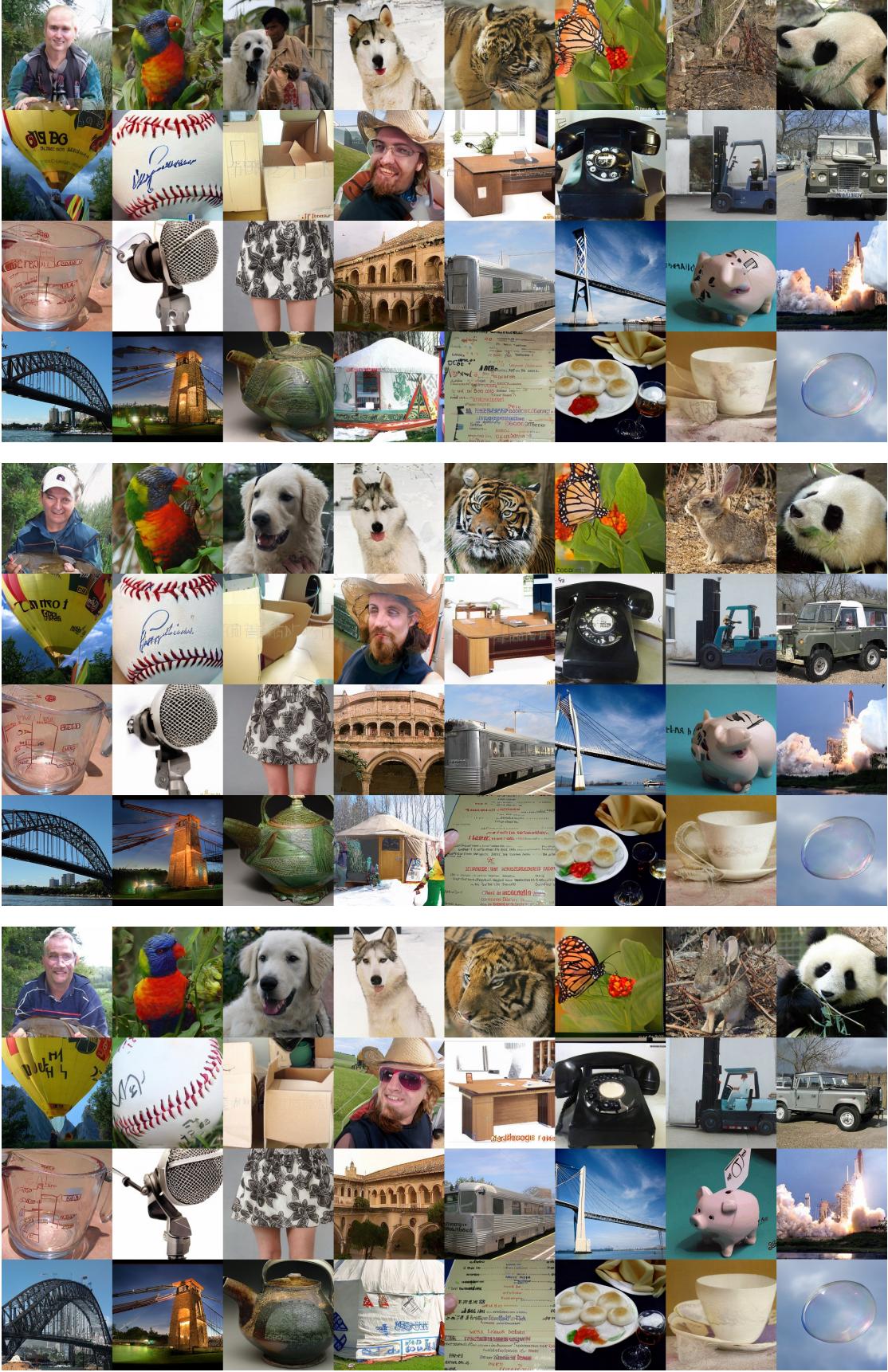

Here is a visual comparison of the VAR model before and after DDO. Notice the reduction in artifacts and the improvement in structural coherence in the DDO samples.

Before DDO (Base VAR-d30, FID 4.74):

After DDO (VAR-d30 + DDO, FID 1.79):

Efficiency

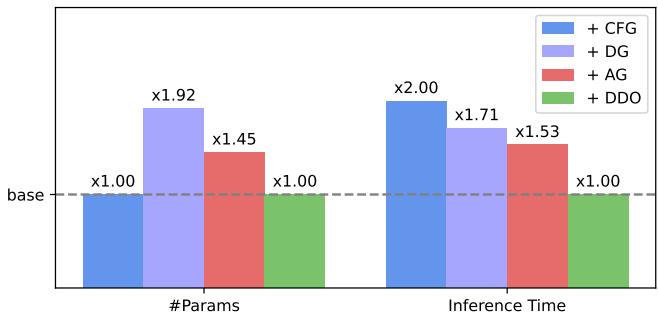

A major advantage of DDO is that it does not change the model architecture. It is purely a fine-tuning objective. This means:

- No extra parameters: You don’t need to ship a discriminator network.

- No inference overhead: The model runs exactly as fast as the base model.

As shown in Figure 5, while other methods like Classifier-Free Guidance (+CFG) or Discriminator Guidance (+DG) increase inference time significantly, DDO (Green bar) keeps the cost identical to the base model.

Conclusion

Direct Discriminative Optimization (DDO) represents a unifying framework that bridges the gap between the two dominant paradigms in generative AI: Likelihood-based modeling and Adversarial training.

By recognizing that a generative model effectively contains its own discriminator (via the likelihood ratio with a reference), the authors have provided a way to fine-tune models to reach their full potential. The method eliminates the “fuzziness” of MLE training, ignores the instability of GAN discriminators, and removes the inference cost of guidance techniques.

For students and researchers, DDO offers a powerful lesson: sometimes the information you need to improve a model is already hidden inside the model itself—you just need the right objective function to unlock it.

As generative models continue to scale, efficient fine-tuning methods like DDO that can squeeze maximum performance out of pre-trained weights will likely become standard tools in the deep learning toolkit.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2503.01103/images/cover.png)