We are living in the era of the “AI Agent.” We have moved past simple chatbots that write poems; we now evaluate Large Language Models (LLMs) on their ability to reason, plan, and interact with software environments. Benchmarks like SWE-Bench test if an AI can fix GitHub issues, while others test if they can browse the web or solve capture-the-flag (CTF) security challenges.

But there is a lingering question in the research community: Do these benchmarks reflect reality?

Often, benchmarks rely on “proxies”—simplified versions of tasks that act as a stand-in for the real thing. A CTF challenge is designed to be solvable; it has a clean setup and a specific “flag” to find. Real-world security vulnerabilities, however, are buried in messy, undocumented, and spaghetti-like codebases.

In a fascinating new paper, AutoAdvExBench, researchers from Google DeepMind and ETH Zurich introduce a benchmark that removes the proxies. They challenge LLMs to perform an actual job done by machine learning security researchers: autonomously breaking defenses against adversarial examples.

The results reveal a startling “reality gap.” While today’s best LLMs can breeze through 75% of “homework-style” security problems, they crash and burn when faced with real academic research code, succeeding only about 13-21% of the time.

Background: The Security Game

To understand this benchmark, we first need to understand the specific domain of security it targets: Adversarial Examples.

In the field of computer vision, an adversarial example is an optical illusion for machines. It is an image (like a picture of a panda) that has been modified with carefully crafted, often invisible, noise. To a human, it still looks like a panda. To a neural network, it looks like a gibbon, a toaster, or an airliner.

The Cat-and-Mouse Game

Over the last decade, thousands of papers have been written on this topic.

- Attackers create algorithms (like FGSM or PGD) to generate these noisy images.

- Defenders propose new model architectures or training methods to resist these attacks.

- Researchers then analyze these defenses to prove they don’t actually work.

This third step is crucial. When a researcher publishes a new defense, other experts try to break it to verify its robustness. This is the exact task AutoAdvExBench assigns to LLMs.

The task is verifiable and objective. If the LLM claims it has broken the defense, we don’t need a human to grade its essay. We simply run the generated adversarial images through the defense model. If the accuracy drops, the LLM succeeded. If the accuracy stays high, the LLM failed.

Building the Benchmark: A Hunt for Real Code

One of the paper’s most significant contributions is the construction of the dataset itself. The researchers did not write synthetic challenges. Instead, they mined the history of AI research to find real implementations of defenses proposed by other scientists.

The process of curating this dataset highlights a crisis in machine learning reproducibility.

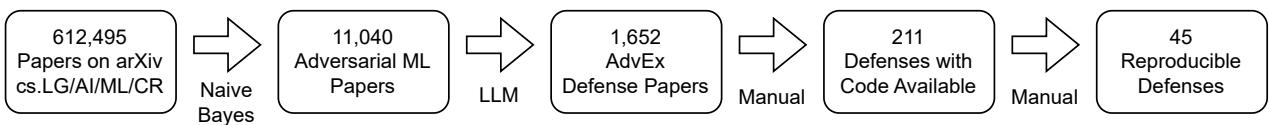

As shown in Figure 1, the authors started with a massive pool of over 600,000 arXiv papers.

- Filtering: They used classifiers and LLMs to narrow this down to 1,652 papers about adversarial defenses.

- Code Availability: They checked which papers actually had links to GitHub repositories.

- Reproducibility: This was the bottleneck. They attempted to run 211 distinct defense implementations.

The result? Only 46 papers (spanning 51 implementations) could be successfully reproduced. The rest failed due to missing files, broken dependencies, ancient libraries (like TensorFlow 0.11), or lack of documentation.

This surviving subset forms the “Real-World” dataset of AutoAdvExBench. It represents code that was written by researchers for researchers—messy, diverse, and not optimized for ease of use.

To provide a comparison, the authors also included a “CTF-subset.” These are 24 defenses taken from a “Self-study course in evaluating adversarial robustness.” These implementations represent the same mathematical defenses found in the real world, but the code was rewritten by experts specifically to be clean, readable, and pedagogically useful (homework-style).

The Agent: How an LLM Attacks AI

You cannot simply paste a research paper into ChatGPT and say, “Break this.” The context window is too small, and the task requires complex planning. The researchers designed a specialized agentic framework to give LLMs the best chance of success.

The agent operates in a loop, writing Python code, executing it, reading the errors or output, and refining its approach. The attack process is broken down into four distinct milestones:

- Forward Pass: The agent must first figure out how to load the defense model and run a single image through it to get a prediction. This proves the agent understands the codebase’s API.

- Differentiable Forward Pass: Most attacks require gradients (mathematical derivatives that tell you which pixels to change to lower the model’s confidence). The agent must ensure the defense code supports backpropagation. This is often the hardest step, as many defenses include non-differentiable pre-processing steps (like JPEG compression) that break standard gradient flow.

- FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method): The agent attempts a simple, one-step attack. This serves as a “sanity check” to ensure the gradients are actually pointing in a direction that harms the model.

- PGD (Projected Gradient Descent): Finally, the agent implements a powerful, iterative attack. If this succeeds, the defense is considered “broken.”

This structured approach allows us to see exactly where the LLMs fail. Are they bad at math? Or can they simply not figure out how to import the right libraries?

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested several state-of-the-art models, including GPT-4o, OpenAI’s o1 (reasoning model), and Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 and 3.7 Sonnet.

The results provide a stark visualization of the difference between “textbook” proficiency and “real-world” capability.

The Homework vs. Reality Gap

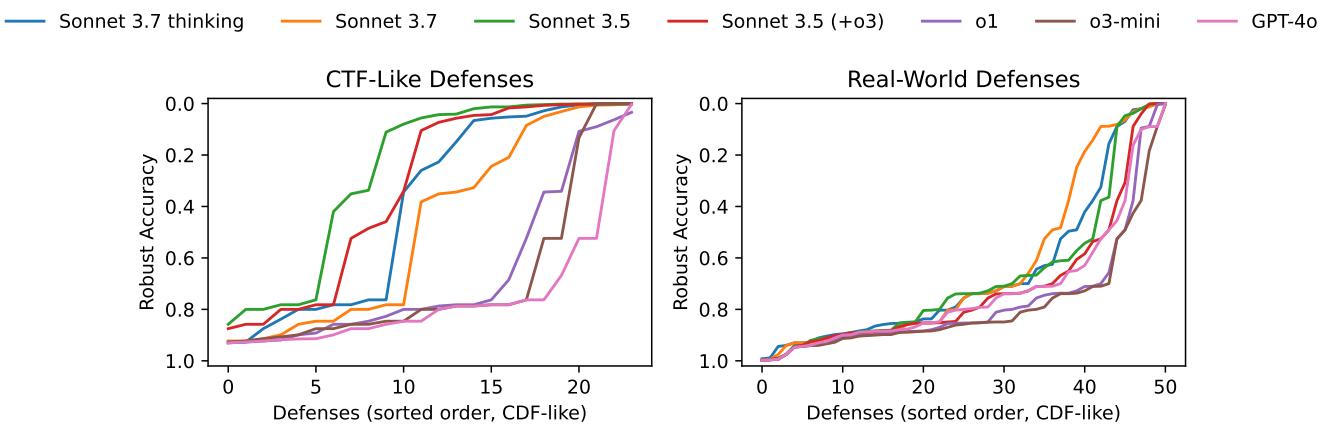

As illustrated in Figure 2, the performance gap is massive.

- CTF-Like Defenses (Left Chart): On the clean, educational code, Claude 3.5 Sonnet is a powerhouse, breaking 75% (18 out of 24) of the defenses. The curves are low, indicating the defenses’ robustness collapsed under the AI’s attack.

- Real-World Defenses (Right Chart): On the actual research code, performance plummets. The strongest agent, Claude 3.7 Sonnet, only manages to break roughly 21% (11 out of 51) of the defenses.

This 50+ percentage point gap validates the premise of the paper: Benchmarks that rely on sanitized, pedagogical problems are overestimating LLM capabilities.

Model Comparison

The breakdown of which models performed best offers some nuanced insights:

- Claude 3.7 Sonnet was the king of the “Real World,” solving the most actual research papers.

- Claude 3.5 Sonnet was actually better at the “CTF” subset than the newer 3.7 version.

- Reasoning Models (o1, o3-mini): Surprisingly, the “reasoning” models often performed worse than the standard models on this task. This mirrors findings in other agentic benchmarks, suggesting that for code manipulation and environment interaction, pure “chain-of-thought” reasoning might be less effective than the flexible coding capabilities of standard models.

Where Do They Fail?

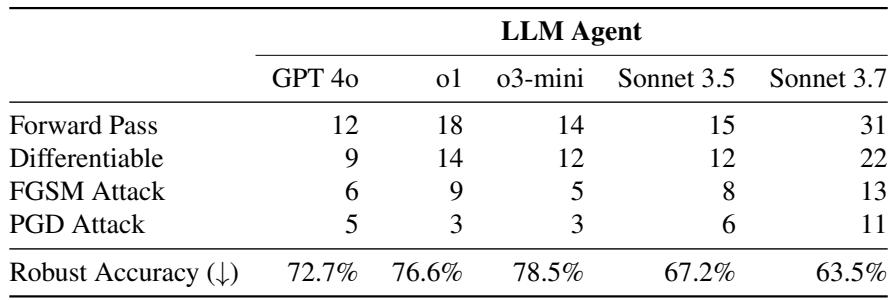

The breakdown of the four milestones (Forward Pass \(\rightarrow\) PGD) reveals that the struggle is incremental.

As Table 1 shows, the biggest filter is simply getting the code to run in a differentiable state.

- Forward Pass: Claude 3.7 could only get a basic forward pass working for 31 out of 51 defenses. This means for nearly 40% of the papers, the AI couldn’t even figure out how to run the software.

- Differentiability: Only 22 defenses were successfully made differentiable. If the AI can’t compute a gradient, it can’t launch a standard attack.

- Final Attack: Only 11 defenses were broken by the full PGD attack using Claude 3.7.

The failures weren’t usually due to a lack of “intelligence” regarding adversarial examples. The models knew what to do (e.g., “I need to implement PGD”). They failed because of software engineering hurdles:

- Old Libraries: Many papers used TensorFlow 1.x. The LLMs kept trying to use TensorFlow 2.x functions, hallucinating methods that didn’t exist in the older versions.

- Messy Structure: Real research code doesn’t always follow PEP-8 standards. The logic is scattered across files, and the LLMs struggled to trace the execution flow.

- Obfuscated Gradients: Some defenses work by “breaking” the gradient (intentionally or not). A human researcher knows to look for a workaround (like estimating the gradient). The LLMs often blindly followed the broken gradient, assuming it was correct, and failed to generate an adversarial image.

Implications and Conclusion

The AutoAdvExBench paper serves as a reality check for the AI community.

First, it demonstrates that we are not yet at the point of “Automated AI Research.” If an agent could solve this benchmark, it would be doing the job of a graduate student or researcher—taking a new paper and experimentally verifying its claims. The low success rates (13-21%) suggest that human researchers are still very much required to navigate the complexities of real-world scientific code.

Second, it highlights the danger of proxy benchmarks. If we only evaluated models on the CTF dataset, we might conclude that AI agents are terrifyingly competent hackers capable of breaking 75% of defenses. This might lead to premature regulation or panic. Conversely, it might lead to a false sense of security if we assume they can patch vulnerabilities they actually can’t understand.

The authors conclude by urging the community to build more “proxy-free” benchmarks. We need to test agents on the messy, chaotic, unpolished data they will encounter in the real world, not just the sanitized puzzles we create for them.

Until LLMs can handle the “spaghetti code” of a 5-year-old research project as well as they handle a LeetCode problem, the gap between AI potential and AI reality will remain significant.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2503.01811/images/cover.png)