Artificial Intelligence has already conquered perfect-information games like Chess and Go. In those domains, Deep Reinforcement Learning (RL) agents—trained over millions of iterations of self-play—reign supreme. However, these methods often require massive, task-specific training resources.

Enter Large Language Models (LLMs). These models possess vast general knowledge, but they notoriously struggle with strategic planning. If you ask a standard LLM to play a game, it often hallucinates rules or fails to look ahead.

This brings us to PokéChamp, a new agent introduced by researchers that achieves expert-level performance in Pokémon battles without any additional training of the LLM. Instead of treating the LLM as a standalone agent, PokéChamp embeds it into a classic game-theory algorithm: Minimax search.

By combining the reasoning and general knowledge of models like GPT-4o with the rigorous planning of Minimax, PokéChamp has achieved a win rate of 76% against state-of-the-art bots and ranked in the top 30%-10% of human players on the competitive ladder. This post explores how the researchers built this system, the architecture behind it, and why Pokémon is such a difficult benchmark for AI.

The Challenge: Why Pokémon?

To understand the significance of PokéChamp, we first need to understand the complexity of competitive Pokémon. Unlike Chess, where both players see the entire board, Pokémon is a Partially Observable Markov Game (POMG).

- Partial Observability: You know your own team, but you do not know the opponent’s full team, their stats, their items, or their move sets until they are revealed.

- Stochasticity: Moves have accuracy checks (they can miss), and critical hits or secondary effects happen randomly.

- State Space: The number of possible states is astronomical. With over 1,000 Pokémon species, combined with items, natures, and effort values (EVs), the estimated state space for just the first turn is \(10^{354}\).

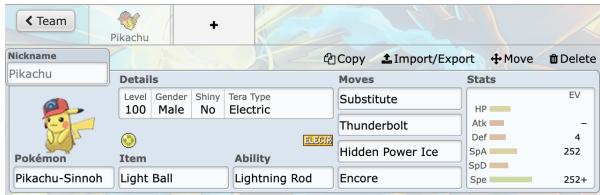

- Teambuilding: Before the battle even starts, players must construct a team of six, configuring intricate details for each character.

As shown in Figure 3, a player must configure moves, abilities, items, and stats for every team member. Because of this complexity, exhaustive search algorithms (like those used in simple Chess engines) are computationally intractable. You cannot simply calculate every possible future outcome.

The Core Method: LLM-Augmented Minimax

The researchers’ primary innovation is not a new model architecture, but a new framework. They utilize a Minimax tree search—a standard algorithm for two-player games—but replace its most computationally expensive and difficult components with an LLM.

In a traditional Minimax search, the agent tries to maximize its reward while assuming the opponent tries to minimize it. The search builds a tree of possible future turns. For Pokémon, building this tree is difficult because the branching factor (the number of possible moves per turn) is huge, and we don’t know the opponent’s hidden information.

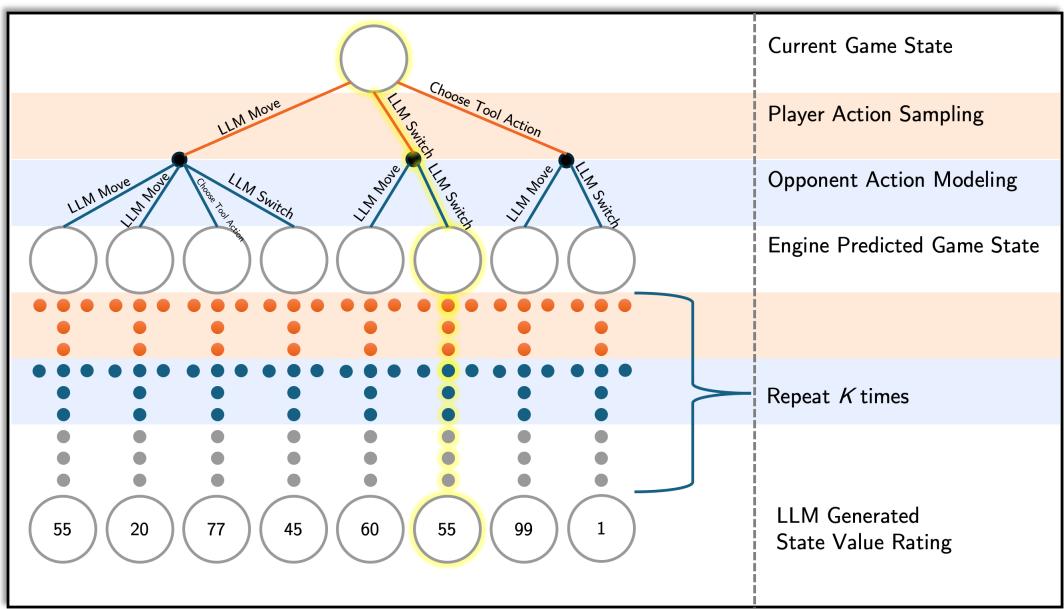

PokéChamp solves this by inserting an LLM into three specific modules of the search process:

- Player Action Sampling: Pruning the tree by suggesting only “good” moves.

- Opponent Modeling: Predicting what the enemy will likely do.

- Value Function Estimation: evaluating who is winning without playing the game to the very end.

Let’s break down this architecture.

1. Player Action Sampling

In a typical turn, a player might have 4 moves per active Pokémon and 5 potential switches, resulting in 9 base options. However, considering the nuances of the game (like Terastallization), the options multiply.

Instead of simulating every single option, PokéChamp prompts the LLM with the current battle state and asks it to sample a small set of viable actions. This acts as a heuristic pruning mechanism. The LLM uses its pre-trained knowledge of Pokémon strategy to discard obviously bad moves (like using a Fire move on a Water type) and focus the tree search on strategic candidates.

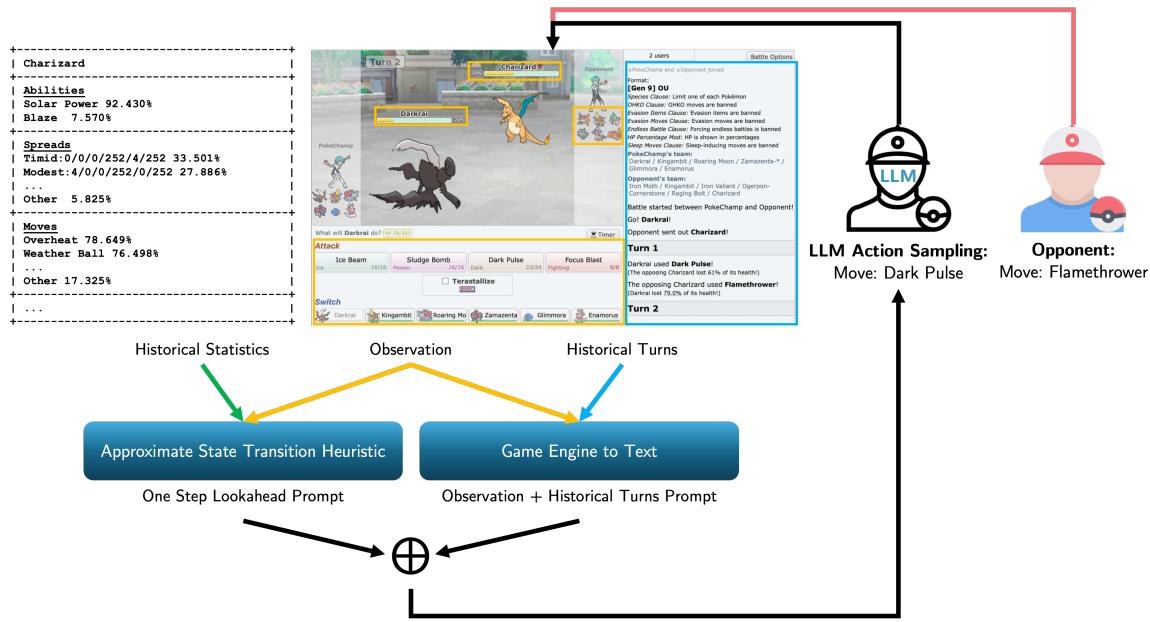

To aid the LLM, the system feeds it an “Approximate State Transition Heuristic.” This is a computed “one-step lookahead” that calculates immediate damage and knock-out potential.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the LLM receives historical statistics (what moves this Pokémon usually runs) and the current observation. It then outputs the most logical moves to populate the search tree.

2. Opponent Modeling

This is the most challenging aspect of a POMG. To plan effectively, you must predict what the opponent will do, even though you don’t know their exact stats or moves.

PokéChamp addresses this by combining historical data with LLM intuition.

- Stat Estimation: The system uses a massive dataset of 3 million real player games to estimate likely stats (Attack, Defense, Speed) for the opponent’s Pokémon.

- Action Prediction: The LLM is prompted to act as the opponent. Given the game state from the opponent’s perspective, the LLM predicts their likely counter-attacks or switches.

This allows the Minimax tree to branch out based on likely opponent behaviors rather than random guesses or worst-case scenarios that are mathematically possible but strategically unlikely.

3. Value Function Estimation

Because Pokémon battles can last for dozens of turns, searching the tree all the way to the end (Game Over) is impossible within the time limits (usually 150 seconds per player total).

The search must stop at a certain depth (\(K\)). At this leaf node, the agent needs to know: Is this state good for me?

Traditionally, this requires a hand-crafted evaluation function (e.g., counting remaining HP). PokéChamp replaces this with the LLM. The model is asked to evaluate the board state based on factors like:

- Type matchups remaining.

- Speed advantages.

- Win probability.

- Negative factors (status ailments, loss of key Pokémon).

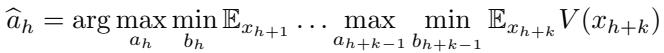

The LLM outputs a score, effectively serving as the heuristic value function \(V(x_{h+k})\) in the modified Minimax equation:

The World Model: Approximating Reality

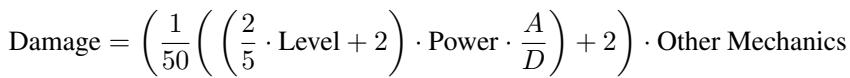

For any search algorithm to work, the agent needs to know the rules of the game—the physics of the world. If I use “Thunderbolt,” how much damage does it do?

PokéChamp utilizes a World Model that approximates game transitions. Since the exact state of the opponent is hidden, the system calculates expected damage using the standard damage formula combined with the estimated stats derived from historical data.

By plugging estimated variables (like Attack \(A\) and Defense \(D\)) into Equation 2, the system simulates the outcome of turns. To handle stochastic elements (like a move with 85% accuracy), the system computes the expected value rather than simulating every probabilistic branch, keeping computation costs manageable.

Experimental Results

The researchers evaluated PokéChamp in the popular Generation 9 OverUsed (OU) format on Pokémon Showdown. This is the standard competitive format for skilled human players.

Performance vs. Bots

PokéChamp was pitted against:

- PokéLLMon: The previous state-of-the-art LLM-based agent.

- Abyssal: A high-level heuristic (rule-based) bot.

- Baselines: Random and Max-Power bots.

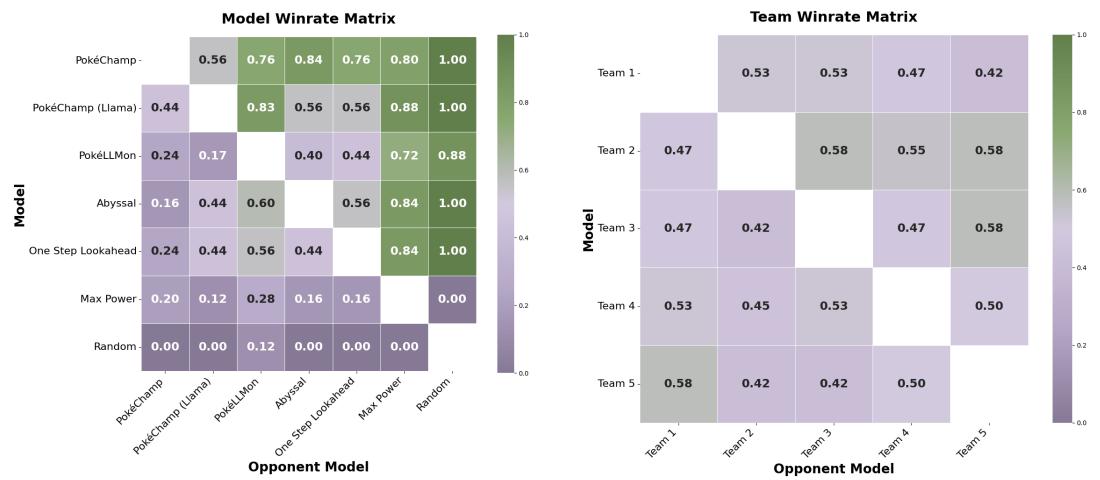

The results were decisive. When powered by GPT-4o, PokéChamp achieved an 84% win rate against the heuristic Abyssal bot and a 76% win rate against PokéLLMon.

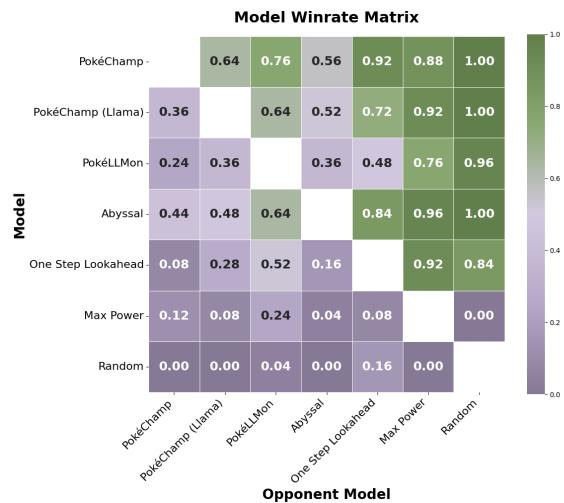

Figure 7 (Left) shows the pairwise win rates. A score of 0.76 in the column against “PokéLLMon” indicates clear dominance. Perhaps more impressively, PokéChamp using the smaller, open-source Llama 3.1 (8B) model also achieved a 64% win rate against PokéLLMon (which uses GPT-4o), proving that the Minimax framework contributes significantly to performance, independent of the model size.

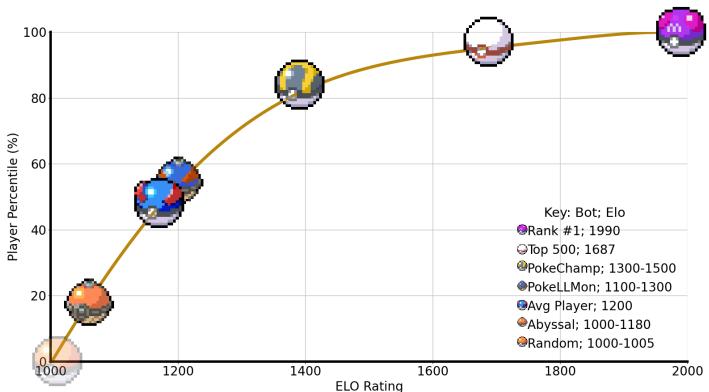

Performance vs. Humans

The ultimate test for a gaming AI is the online ladder. The researchers deployed PokéChamp anonymously on the Pokémon Showdown ladder.

The agent achieved a projected Elo rating of 1300-1500. While Elo numbers vary by game, on this specific ladder, this rating places the agent in the top 30% to 10% of human players.

As shown in Figure 1, the gold Poké Ball represents PokéChamp. It sits significantly higher on the curve than the average player and previous LLM methods (Blue Ball), approaching the territory of elite human players.

Handling Complex Mechanics

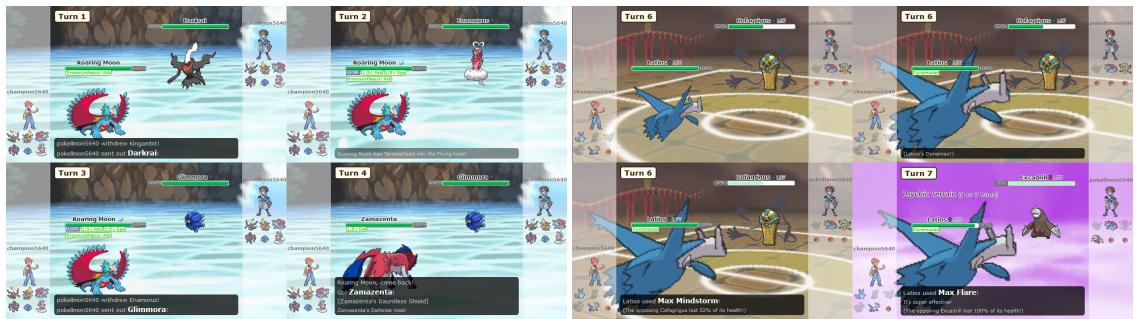

One of the criticisms of previous language agents is that they fail to utilize generation-specific mechanics like Terastallization (changing a Pokémon’s type mid-battle) or Dynamax.

The benchmarks showed that PokéChamp correctly identifies when to use these mechanics to flip a losing matchup into a winning one.

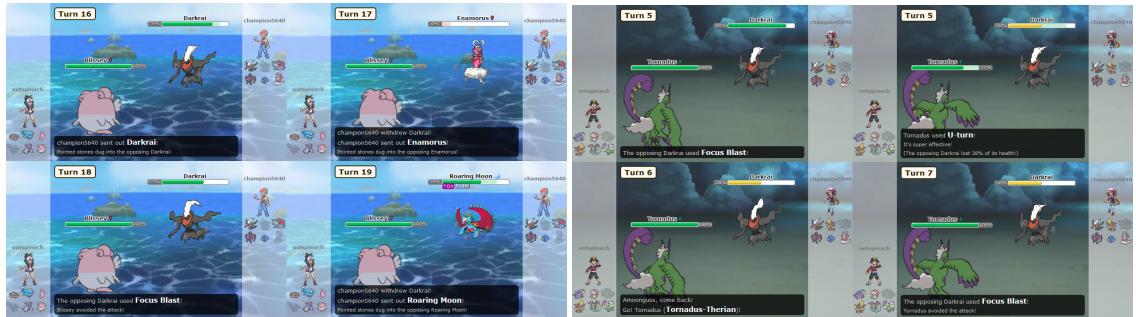

In Figure 6 (Left), PokéChamp identifies that its Pokémon (Roaring Moon) is weak to the opponent. It triggers Terastallization to change its defensive profile, surviving the hit. This level of tactical awareness highlights the benefit of the lookahead search provided by the Minimax framework.

Robustness in Random Battles

The team also tested the agent in “Random Battles,” a format where teams are randomized every game. This tests adaptability rather than pre-planning.

Even in this chaotic environment, PokéChamp (GPT-4o) maintained a 70% win rate against the heuristic bot. The matchup matrix in Figure 9 visualizes the consistency of the agent across different opponents.

Limitations: Where Does it Fail?

Despite its success, PokéChamp is not invincible. The researchers identified two specific strategies that human players use to exploit the AI:

- Stall Strategies: “Stall” teams focus on extreme defense and passive damage. Because PokéChamp has a limited lookahead depth (due to time constraints), it often fails to see the long-term danger of a slow death. It tends to switch excessively, trying to find an immediate advantage that doesn’t exist.

- Excessive Switching: Expert humans can manipulate the AI by constantly switching characters. If the AI predicts a move based on the current Pokémon, but the opponent switches to a counter immediately, the AI’s move may fail.

Figure 8 illustrates these failures. On the left, PokéChamp keeps switching Pokémon in a loop, taking hazard damage each time, unable to commit to a breakthrough strategy against a defensive “Stall” wall.

Conclusion and Implications

PokéChamp demonstrates a pivotal shift in how we apply Large Language Models to complex tasks. Rather than training a model to “be” the player, the researchers used the LLM as a sophisticated reasoning engine within a classical planning algorithm.

The key takeaways are:

- No Training Required: The system uses off-the-shelf models (GPT-4o, Llama 3).

- Plug-and-Play Reasoning: The LLM replaces the hard-to-code heuristic parts of Minimax (evaluation and opponent modeling).

- Expert Performance: It competes with top-tier human players in a partially observable environment.

This approach suggests that the future of game AI—and perhaps decision-making AI in general—may not lie solely in bigger models or more reinforcement learning, but in better architectural integration of LLMs into proven algorithmic frameworks. By constraining the LLM’s vast knowledge with the strict logic of a tree search, PokéChamp minimizes hallucinations and maximizes strategic depth.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2503.04094/images/cover.png)