Understanding the brain is fundamentally a translation problem. On one side, we have the biological reality: neurons firing electrical spikes in complex, rhythmic patterns. On the other side, we have the observable output: movement, choices, and behavior.

For decades, computational neuroscience has treated this translation as two separate, distinct tasks. If you use behavior to predict neural activity, you are performing neural encoding. If you use neural activity to predict behavior, you are performing neural decoding. Historically, models were designed to do one or the other. You built an encoder to understand how the brain represents the world, or a decoder to control a robotic arm with neural signals.

But the brain does not operate in a vacuum. The relationship between neural activity and behavior is bidirectional and deeply intertwined. To truly understand neural computation, we need a unified framework that can fluently speak both languages.

In this post, we will dive deep into a new paper titled “Neural Encoding and Decoding at Scale” (NEDS). This research introduces a multimodal foundation model that achieves state-of-the-art performance by learning to translate seamlessly between spikes and actions using a novel “multi-task-masking” strategy.

The Two-Way Street of Neuroscience

Before understanding the solution, we must clearly define the problem. The relationship between what neurons do and what an animal does is governed by complex probabilities.

- Encoding (\(P(\text{Neural} | \text{Behavior})\)): This asks, “Given that the animal moved its hand to the left, what is the probability that neuron X fired?” This helps us understand the receptive fields and tuning properties of neurons.

- Decoding (\(P(\text{Behavior} | \text{Neural})\)): This asks, “Given that neuron X and Y fired, what is the probability the animal is moving its hand?” This is the basis of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs).

Recent advances in AI have given us “large-scale models” trained on massive amounts of data. In neuroscience, models like POYO+ or NDT2 have applied Transformer architectures to neural data with great success. However, these models generally specialize. They are either great decoders or great encoders, but rarely both. This creates a fragmentation in our tools—we are effectively building separate dictionaries for English-to-French and French-to-English, losing the nuanced context that comes from understanding the language as a whole.

Enter NEDS: A Unified Foundation Model

The researchers propose NEDS (Neural Encoding and Decoding at Scale) to bridge this gap. NEDS is a multimodal transformer. In the world of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4, “multimodal” usually means text and images. Here, the modalities are neural spikes and behavioral variables (like wheel speed, whisker motion, or choice).

The core insight of NEDS is that by training a single model to solve multiple masking tasks simultaneously, the model learns a robust internal representation of the brain state that benefits both encoding and decoding.

The Architecture of Translation

How do you feed spikes and movement into the same neural network? The answer lies in tokenization. Transformers operate on sequences of tokens. NEDS treats neural activity and behavior as two parallel sequences that need to be aligned.

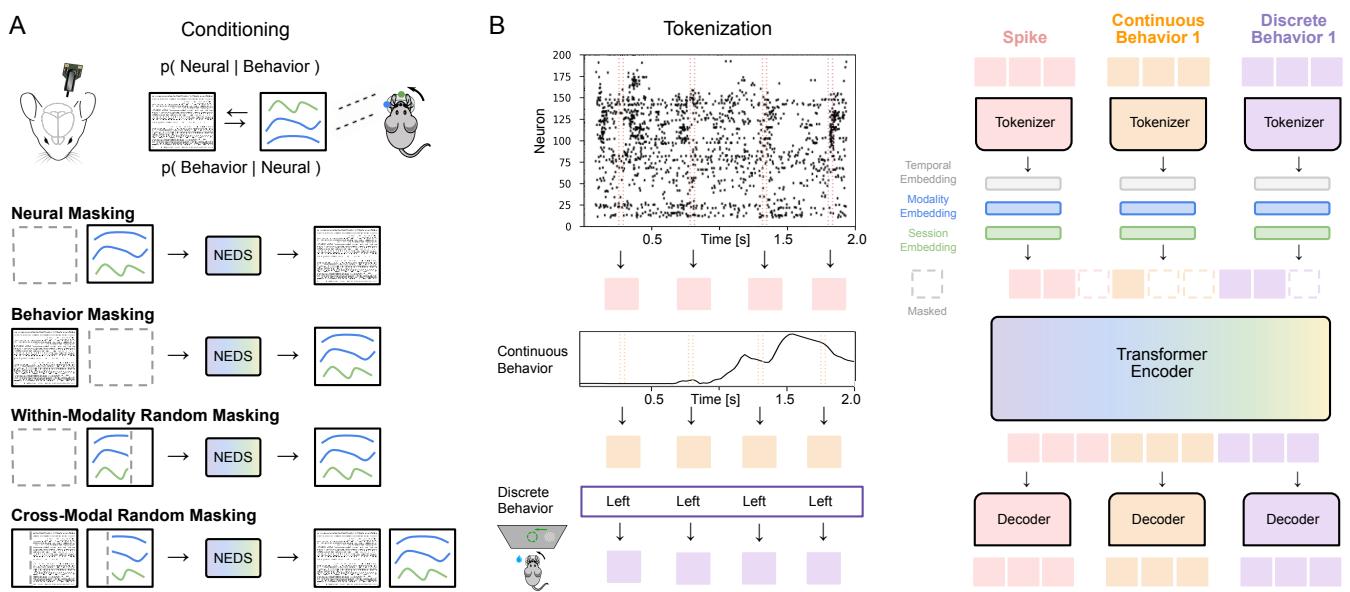

As shown in Figure 1, the architecture is designed to handle the disparate nature of the data:

- Neural Data: The spikes are binned into 20ms windows. A “Neural Tokenizer” converts these spike counts into vector embeddings.

- Continuous Behavior: Variables like wheel speed are also binned at 20ms. A specific tokenizer converts these continuous values into embeddings.

- Discrete Behavior: Variables like a “Left/Right” choice are categorical. These are repeated across the trial duration to align with the time-series data.

Once tokenized, the model adds embeddings for time (temporal position), modality (is this a neuron or a behavior?), and session (which animal is this?). These tokens are then concatenated and fed into a standard Transformer Encoder.

The Core Innovation: Multi-Task-Masking

The “secret sauce” of NEDS is how it is trained. The authors utilize a technique called Masked Modeling, popularized by models like BERT in language and MAE in computer vision. The idea is simple: hide parts of the data and force the model to guess the missing pieces.

However, standard random masking isn’t enough to force the model to learn the relationship between brain and behavior. NEDS introduces a Multi-Task-Masking strategy that alternates between four specific objectives (illustrated in Figure 1A):

- Neural Masking (Encoding): The model hides the neural tokens and sees only the behavior. It must predict the neural activity. This explicitly trains the conditional expectation \(\mathbb{E}[X | Y]\).

- Behavior Masking (Decoding): The model hides the behavior tokens and sees only the neural activity. It must predict the behavior. This trains \(\mathbb{E}[Y | X]\).

- Within-Modality Random Masking: Random chunks of neural data are hidden and predicted from other neural data (and same for behavior). This forces the model to learn the internal dynamics of a single modality (e.g., “if neuron A fires, neuron B usually fires 10ms later”).

- Cross-Modal Random Masking: Random chunks are hidden across both modalities. The model must use whatever clues are available—neural or behavioral—to reconstruct the missing data. This encourages the model to learn the joint probability distribution.

By constantly switching between these tasks during training, NEDS does not just memorize patterns; it learns the causal and correlational structures connecting the brain to action.

The Mathematical Framework

To formalize this, the authors define a generative process. The goal is to maximize the likelihood of the data given the model parameters.

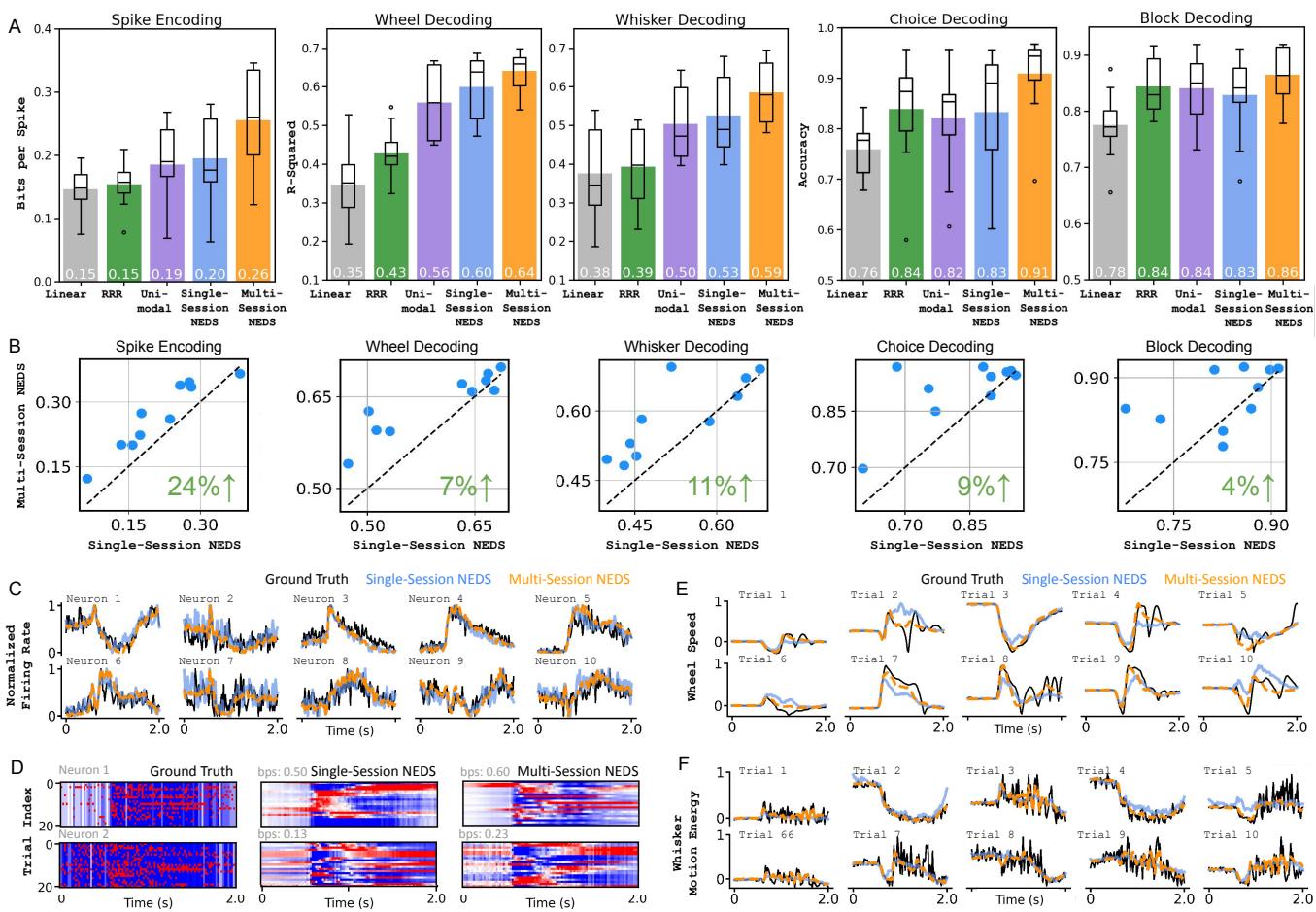

Let’s break down the equation above:

- Tokenization (\(Z_X, Z_Y\)): The raw inputs are projected into a latent space.

- Masking (\(M \odot ...\)): The mask \(M\) is applied based on one of the four strategies described above.

- Positional Embeddings (\(Z_{pos}\)): The model adds context: Modality (Brain vs. Behavior), Temporal (Time \(t\)), and Session (Mouse ID).

- Transformer: The core mechanism that processes the sequence.

- The Output Heads (\(X \sim, Y \sim\)):

- For Neural Activity, the model predicts a firing rate \(\lambda\). Since spike counts are discrete and non-negative, the loss function is based on a Poisson distribution.

- For Continuous Behavior (like speed), it minimizes Mean Squared Error (MSE).

- For Discrete Behavior (like choice), it uses Cross-Entropy loss.

This unified objective function allows the model to optimize for all tasks simultaneously using gradient descent.

Experimental Results: Validating the Foundation

The researchers evaluated NEDS on a massive dataset from the International Brain Laboratory (IBL). This dataset contains recordings from 83 mice performing the exact same decision-making task, targeting the same brain regions. This standardization makes it perfect for testing large-scale models.

Scaling Up: The Power of Multi-Session Training

A key hypothesis in modern AI is that “more data is better.” Does training on 73 different mice help the model predict the activity of a 74th, unseen mouse?

The authors compared Single-Session NEDS (trained only on the specific mouse being tested) against Multi-Session NEDS (pre-trained on 73 animals, then fine-tuned on the target).

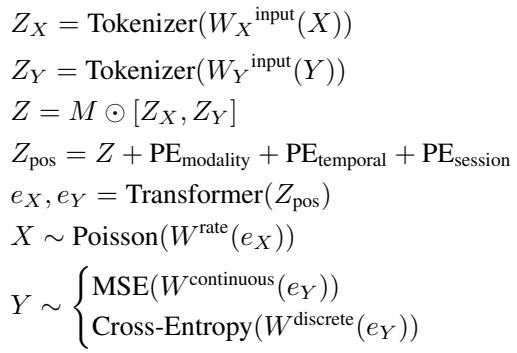

The results in Figure 2 are compelling:

- Panel A: Multi-session NEDS (the orange box) consistently achieves the highest scores across all metrics. For neural encoding, it reaches nearly 0.27 bits/spike (bps), significantly higher than linear baselines or single-session models.

- Panel B: The scatter plots show a direct comparison. Each dot is a session. Because almost all dots are above the diagonal line, we confirm that pre-training on other animals significantly boosts performance on the target animal.

- Spike Encoding saw a massive 24% improvement.

- Wheel Decoding improved by 7%.

- Qualitative traces (C-F): Look at the orange lines in Panel C. The Multi-session predictions track the ground truth (black) much more closely than the blue single-session lines. This suggests the model uses its “general knowledge” of mouse brain dynamics to fill in gaps that a single-session model finds noisy.

Comparison to State-of-the-Art

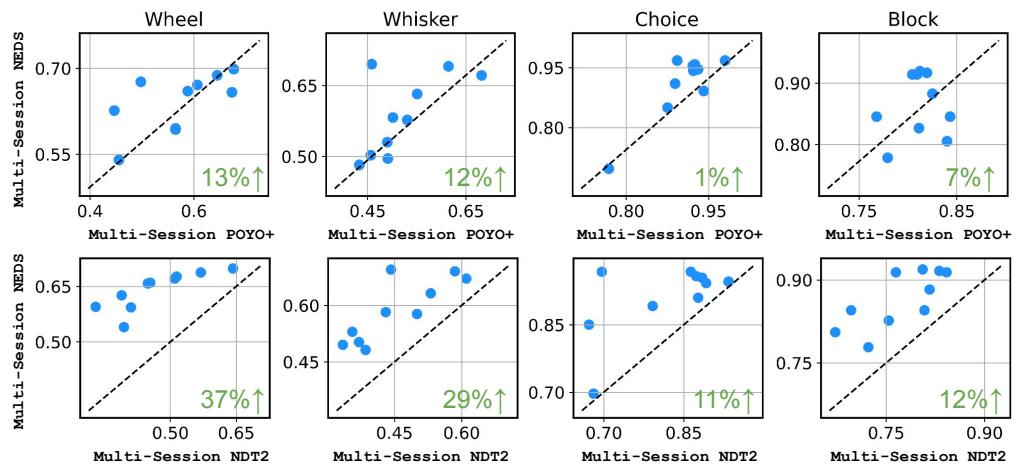

How does NEDS compare to other heavy hitters in the field, specifically POYO+ (a dedicated decoding model) and NDT2 (a masked modeling approach)?

The authors pre-trained all models on the same 74 sessions and fine-tuned them on held-out animals.

Figure 3 illustrates the dominance of NEDS:

- Vs. POYO+ (Top Row): POYO+ is a strong competitor, specialized for decoding. NEDS matches or slightly beats it (e.g., +13% on Wheel decoding), while maintaining the ability to do encoding (which POYO+ cannot do).

- Vs. NDT2 (Bottom Row): NEDS significantly outperforms NDT2, with a 37% improvement in wheel decoding and 29% in whisker decoding.

This validates the hypothesis that the multimodal nature of NEDS—seeing both spikes and behavior during pre-training—creates a superior latent representation compared to models that only see neural data (NDT2) or only optimize for decoding tasks (POYO+).

Emergent Properties: The Brain Region Map

Perhaps the most fascinating result in the paper is an emergent property of the model. The model was never explicitly told which brain region a neuron belonged to. It was simply fed spike trains and behavior.

However, each neuron has a learned “embedding”—a vector representation inside the model. The researchers visualized these embeddings to see if the model had learned anything about neuroanatomy.

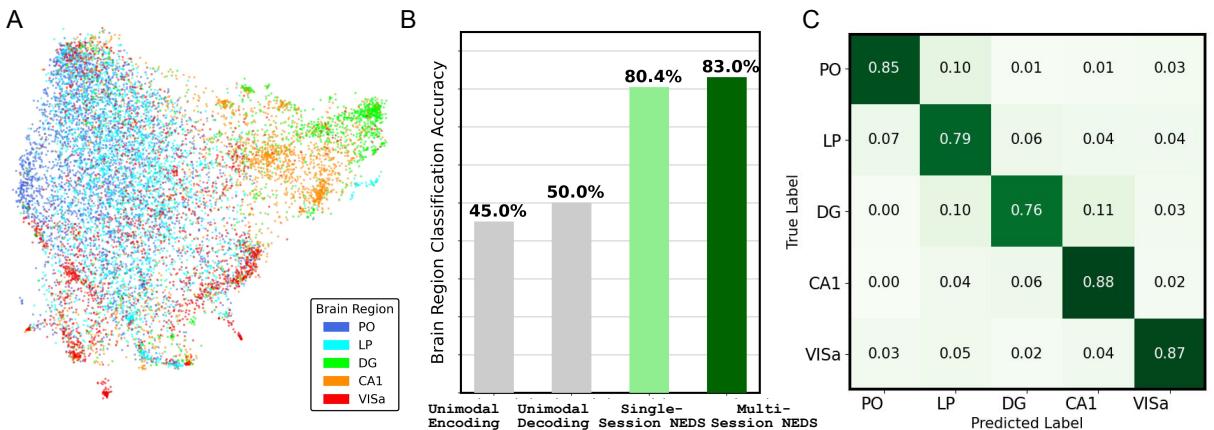

Figure 4A shows a UMAP projection of these embeddings. The dots organize themselves into distinct clusters corresponding to anatomical regions like the Hippocampus (CA1, DG), Visual Cortex (VISa), and Thalamus (PO, LP).

- Panel B: When a classifier is trained on these embeddings to predict brain region, Multi-Session NEDS achieves 83% accuracy. This is significantly higher than unimodal models (around 45-50%).

- Interpretation: This implies that the functional role of a neuron (how it fires and relates to behavior) is so distinct that a sufficiently powerful model can “rediscover” the brain’s anatomy purely from functional data.

- Panel C (Confusion Matrix): The errors are also instructive. The model sometimes confuses PO and LP (posterior thalamus). As the authors note, these regions are anatomically adjacent and functionally similar, suggesting the “mistake” is actually a reflection of biological reality.

Conclusion

NEDS represents a significant step forward in computational neuroscience. By treating neural encoding and decoding not as separate problems but as two sides of the same conditional probability coin, the researchers have built a more robust and generalizable model.

The key takeaways are:

- Unification: A single architecture can achieve state-of-the-art results in both predicting spikes and predicting behavior.

- Masking Matters: The multi-task-masking strategy is essential for learning the joint distribution of diverse modalities.

- Scale Wins: Pre-training on many animals allows the model to learn general neural dynamics that transfer to new individuals.

- Emergence: Large-scale training reveals biological structure (like brain regions) without explicit supervision.

As datasets grow larger and more diverse, approaches like NEDS move us closer to a “Foundation Model of the Brain”—a universal translator that can interpret neural activity across subjects, regions, and tasks, potentially revolutionizing everything from basic research to clinical brain-computer interfaces.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2504.08201/images/cover.png)