Building Better Protein Models: How to Fix the “Structure Gap” in Multimodal AI

Proteins are the molecular machinery of life. To understand biology—and to design new drugs—we need to understand two different “languages” of proteins: their sequence (the string of amino acids) and their structure (how they fold into 3D shapes).

Historically, AI has treated these as separate problems. You had models like ESM for reading sequences and models like AlphaFold for predicting structures. But recently, researchers have been trying to merge these into Multimodal Protein Language Models (PLMs). Ideally, a single model should be able to read a sequence, understand its geometry, and generate new proteins that are both chemically valid and structurally sound.

However, there is a catch. Current multimodal models struggle to capture the fine-grained details of 3D structures. They often rely on “tokenizing” 3D coordinates into discrete symbols, a process that loses information.

In a recent paper, Elucidating the Design Space of Multimodal Protein Language Models, researchers systematically deconstruct this problem. They identify why current models fail and propose a suite of solutions—spanning generative modeling, architecture design, and data strategies—that dramatically improve performance.

In this post, we’ll break down their findings and explain how they managed to make a 650M parameter model outperform 3B parameter baselines in protein folding.

The Problem: When Tokenization Fails

To feed a 3D protein structure into a Language Model (which expects text-like inputs), we usually use a Structure Tokenizer. This converts continuous 3D coordinates (\(x, y, z\)) into a sequence of discrete integers (tokens), similar to how words are tokenized in ChatGPT.

The researchers analyzed DPLM-2, a state-of-the-art multimodal model, and identified three major bottlenecks in this process:

- Information Loss: Turning continuous coordinates into discrete tokens acts like a lossy compression algorithm. You lose the fine details.

- The “Reconstruction” Trap: A tokenizer might be good at compressing and decompressing a structure (reconstruction), but that doesn’t mean the language model can generate those tokens effectively.

- The Index Prediction Problem: Predicting the exact index of a token (e.g., “Token #4532”) is incredibly hard. The model often gets the specific index wrong, even if the structural concept is close.

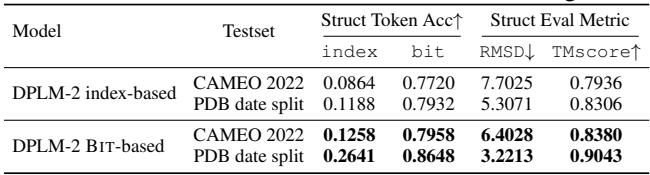

As shown in the table below, while the model struggles to predict the exact index (only ~8-12% accuracy), it is actually much better at predicting the underlying bits (binary representation) of the structure (~77-86% accuracy).

This observation—that the model “knows” the structure better than the discrete indices suggest—forms the basis of their first major improvement.

Solution 1: Improved Generative Modeling

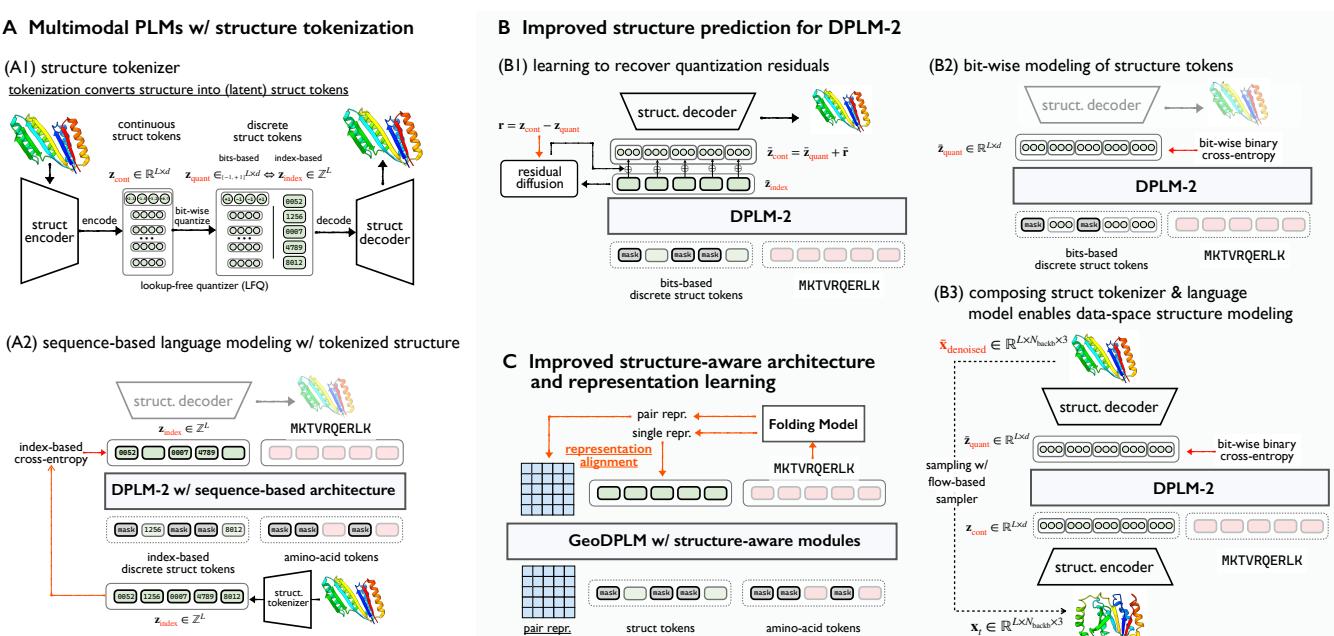

The researchers proposed a new design space to fix these generative issues, summarized in the figure below.

Bit-wise Discrete Modeling

Since predicting one specific integer out of thousands is difficult (and prone to error), the researchers shifted the supervision target. Instead of predicting the token index, they trained the model to predict the bits that make up that token.

This leverages the “Lookup-Free Quantization” (LFQ) method used in the tokenizer. If a token is represented by a binary code (e.g., 10110), predicting each bit independently is a much easier classification task than picking one number out of a dictionary of 262,144 options. This creates a “finer-grained” supervision signal that is easier for the model to learn.

Recovering Lost Details with RESDIFF

Even with perfect token prediction, the discrete tokens are still a “lossy” compression of the 3D structure. To fix this, the team introduced a lightweight Residual Diffusion (ResDiff) module.

Think of the discrete tokens as a “low-resolution” scaffold of the protein. The ResDiff module acts as a polisher; it learns the “residuals”—the difference between the blocky tokenized structure and the smooth, real-continuous structure.

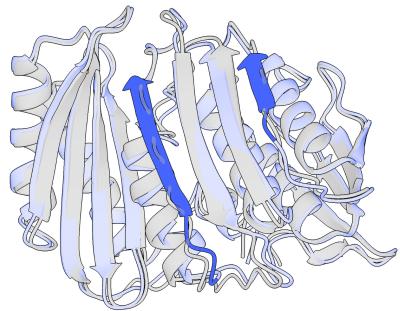

The visual impact of this is striking. In the figure below, you can see how the residual diffusion (blue) refines the initial prediction (gray), fixing broken loops and aligning the secondary structures more tightly.

Solution 2: Geometric Architecture (GeoDPLM)

Standard Language Models are designed for 1D sequences (text). Proteins, however, are fundamentally geometric objects governed by physics and spatial relationships. Treating a protein purely as a 1D string of tokens ignores this reality.

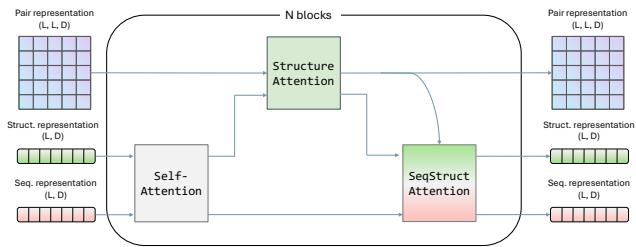

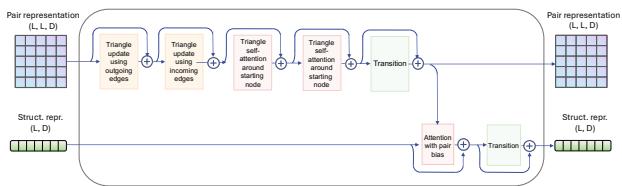

To address this, the researchers introduced GeoDPLM, which integrates “geometry-aware” modules into the architecture.

Inspired by AlphaFold, GeoDPLM introduces two key concepts into the PLM:

- Pair Representations: Instead of just looking at single residues, the model explicitly calculates and updates information about pairs of residues (how residue \(i\) relates to residue \(j\)).

- Triangle Updates: These are specialized mathematical operations that enforce geometric consistency (e.g., if point A is close to B, and B is close to C, A must be relatively close to C).

The researchers added a Structure Attention Module (shown below) that processes these pair representations alongside the standard sequence information.

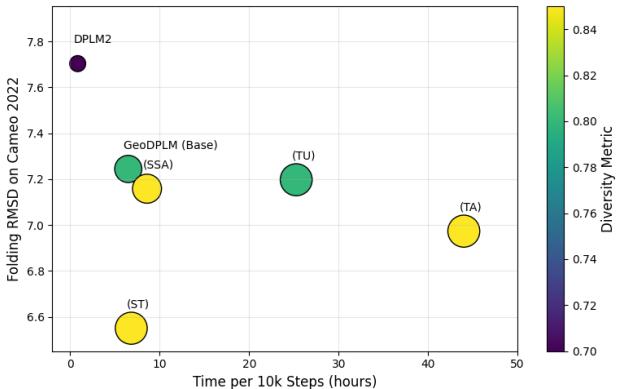

The Trade-off: While these geometric modules significantly improve folding accuracy (lowering RMSD), they are computationally expensive. The “Triangle Attention” mechanism, for instance, slowed down training by nearly 7x. The researchers found a sweet spot (GeoDPLM Base) that uses transition layers and pair biases to get most of the benefits without the massive speed penalty.

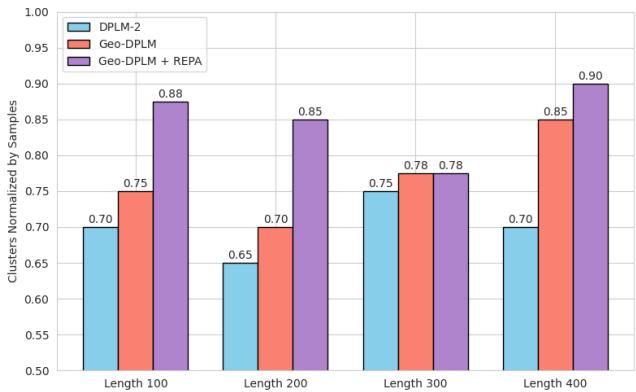

Solution 3: Representation Alignment (REPA)

The third pillar of improvement is Representation Alignment (REPA).

The idea is simple: We already have specialized “folding models” (like ESMFold) that are excellent at understanding structure. Why not distill their knowledge into our multimodal model?

Instead of just training the model on discrete tokens (which are “sharp” and harsh targets), the researchers forced the PLM’s internal representation to align with the rich, continuous representations from ESMFold. This provides a smoother, high-dimensional learning signal.

Why does this matter? It drastically improves diversity. Multimodal PLMs often suffer from “mode collapse,” where they generate very similar structures over and over. As seen in the chart below, adding REPA (the purple bars) significantly increases the diversity of the generated proteins compared to the base model.

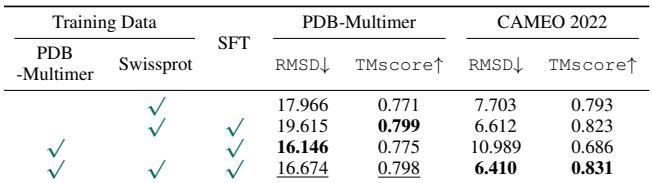

The Role of Data: Monomers vs. Multimers

Most protein language models are trained only on monomers (single protein chains). But biology is interactive; proteins form complexes called multimers.

The researchers curated a dataset called PDB-Multimer and found an interesting relationship:

- Training on multimer data helps the model understand interactions between chains.

- Crucially, training on multimers improves performance on monomers.

This suggests that the “grammar” of protein structure is universal. Learning how two separate chains interact helps the model understand how a single chain folds onto itself. The table below shows that fine-tuning with multimer data improves reconstruction and folding metrics for complex cases.

Putting It All Together: The Results

So, what happens when you combine Bit-wise modeling, Geometric architecture, and Representation Alignment?

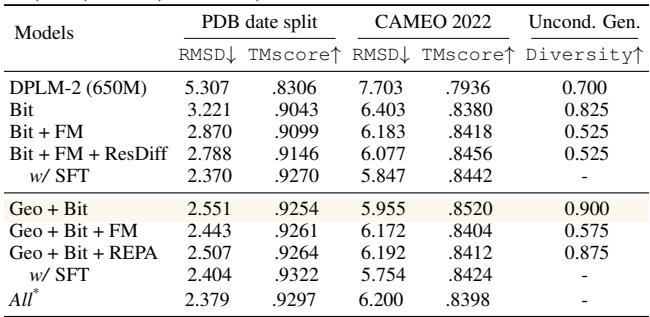

The researchers tested their methods on the standard “Protein Folding” task (predicting structure from sequence). The metric used is RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation)—lower is better.

- Baseline (DPLM-2): 5.52 Å

- With Bit-wise Modeling: 3.22 Å (Huge jump!)

- With Geo + Bit-wise + SFT (Supervised Finetuning): 2.36 Å

Remarkably, their 650M parameter model outperformed the 3B parameter baseline (ESMFold is ~3B) on the PDB dataset.

The following table summarizes the orthogonality of these methods. The “Recommended Setting” (Geo + Bit) offers the best balance of performance and efficiency.

Conclusion

This research highlights that simply throwing more data at a standard Language Model isn’t enough for multimodal protein generation. The design of the supervision signal (bits vs. indices) and the inductive bias of the architecture (geometric modules) play a massive role.

By “elucidating this design space,” the authors have provided a blueprint for the next generation of Protein AI. These models are not just predicting static structures; they are learning a unified representation of protein form and function, paving the way for more accurate de novo protein design.

Key Takeaways:

- Don’t predict indices; predict bits. It’s a more effective way to teach structure to a PLM.

- Geometry matters. You can’t treat 3D structures strictly as 1D text; you need geometric modules.

- Distillation helps. Aligning with specialized folding models improves generative diversity.

- Multimers matter. Data from protein complexes helps models understand single proteins better.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2504.11454/images/cover.png)