Introduction

In the world of robotics, data is currency. Over the last few years, we have seen a massive surge in the capabilities of robot policies, largely driven by Imitation Learning (IL). The formula seems simple: collect a massive dataset of a human expert performing a task (like folding a towel or opening a door), and train a neural network to copy those movements.

However, there is a catch. This “expert data” is incredibly expensive. It requires humans to teleoperate robots for hours, meticulously labeling every state with a precise action. Meanwhile, there exists a vast ocean of “cheap” data that we mostly ignore: videos of robots attempting tasks and failing (suboptimal data), or videos of humans or robots doing things without the specific motor commands recorded (action-free data).

Standard approaches, like the state-of-the-art Diffusion Policy, struggle to use this cheap data. Because they map visual observations directly to actions, they require the action labels to be present and optimal. If the action is missing or wrong, the model learns nothing—or worse, it learns the wrong thing.

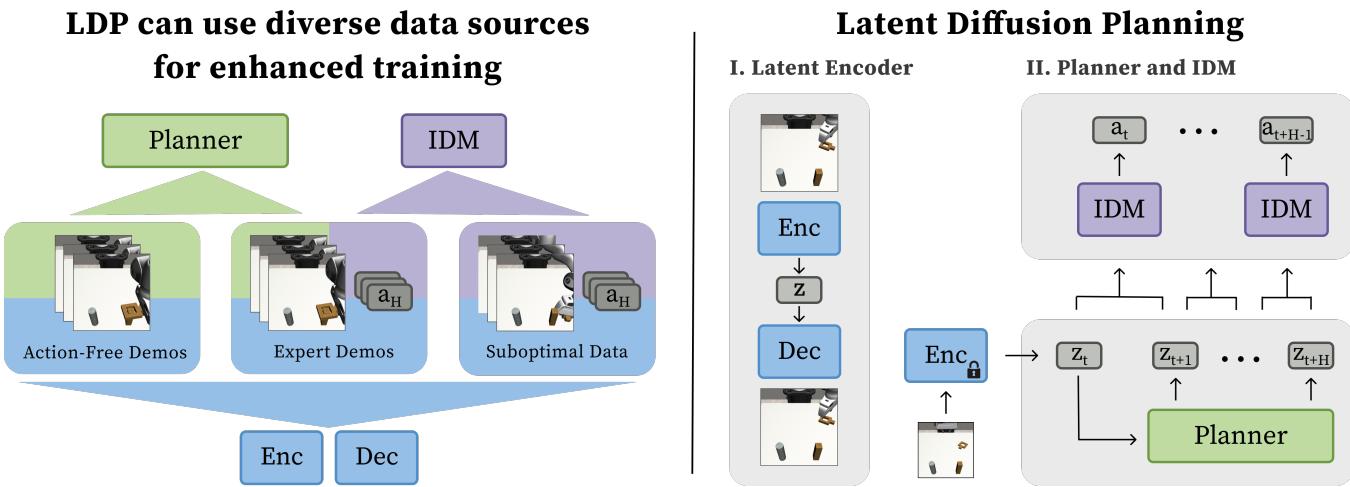

Enter Latent Diffusion Planning (LDP). This new approach, proposed by researchers from Stanford and UC Berkeley, fundamentally changes how robots learn by separating the what from the how. By splitting the learning process into planning future states and figuring out the actions to get there, LDP can feast on the cheap, messy data that other models throw away.

In this post, we will tear down the LDP architecture, explain how it leverages diffusion models in a novel way, and analyze how it manages to outperform state-of-the-art baselines by learning from failure and observation.

Background: The Data Problem in Imitation Learning

To understand why Latent Diffusion Planning is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of current Imitation Learning (IL) methods.

Behavior Cloning and Diffusion Policy

The standard IL framework is Behavior Cloning (BC). You have a dataset of pairs: an image of the world (\(x_t\)) and the action the expert took (\(a_t\)). The goal is to learn a policy \(\pi\) such that \(\pi(x_t) \approx a_t\).

Recently, Diffusion Policy has become the gold standard for this. It treats the robot’s action sequence as a “denoising” problem. Starting with random noise, it iteratively refines the noise until it becomes a smooth, expert-like trajectory of actions.

While powerful, these methods have a rigid requirement: \((x_t, a_t)\) pairs must be optimal.

- Action-Free Data: If you have a video of a robot moving but no record of the motor torques (actions), a standard BC agent cannot learn from it. It doesn’t know what \(a_t\) to predict.

- Suboptimal Data: If you have a log of a robot trying to pick up a cup and missing, a standard BC agent trained on this will learn to miss the cup.

The Promise of Modular Learning

The researchers behind LDP propose a modular solution. Instead of learning a direct mapping from image to action, they split the problem into two distinct phases:

- The Planner: Looks at the current world and imagines a “movie” of the future states where the task is solved. Crucially, this only deals with states, not actions.

- The Inverse Dynamics Model (IDM): Looks at two consecutive frames of that “movie” and figures out the action needed to move from one to the other.

This separation is the key to unlocking cheap data. You can train the Planner on videos without actions (action-free data). You can train the IDM on messy robot logs (suboptimal data) to understand physics, even if the overall plan was bad.

Core Method: Latent Diffusion Planning

Latent Diffusion Planning (LDP) is composed of three distinct training stages: learning a compressed latent space, training the planner, and training the inverse dynamics model.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the architecture moves away from predicting actions directly. Instead, it forecasts a dense sequence of future states in a latent space. Let’s break down each component.

1. Learning a Compact Latent Space (\(\beta\)-VAE)

Planning directly in “pixel space” (generating high-resolution video frames of the future) is computationally heavy and difficult. A video generation model has to worry about lighting, textures, and background details that are irrelevant to the robot’s task of moving an object.

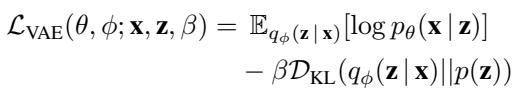

To solve this, LDP essentially “zips” the images into a compressed format called a Latent Embedding (\(z\)). It uses a \(\beta\)-Variational Autoencoder (VAE).

The VAE consists of:

- Encoder (\(\mathcal{E}\)): Takes an image \(x\) and squashes it into a low-dimensional vector \(z\).

- Decoder (\(\mathcal{D}\)): Takes vector \(z\) and tries to reconstruct the original image \(x\).

The training objective balances reconstruction quality with a regularization term (KL divergence) to keep the latent space smooth:

Here, \(\beta\) controls how structured the latent space is. By training this on all available data (expert, suboptimal, and action-free), the robot learns a compact representation of the world where mathematically similar vectors represent visually similar states.

2. The Latent Planner

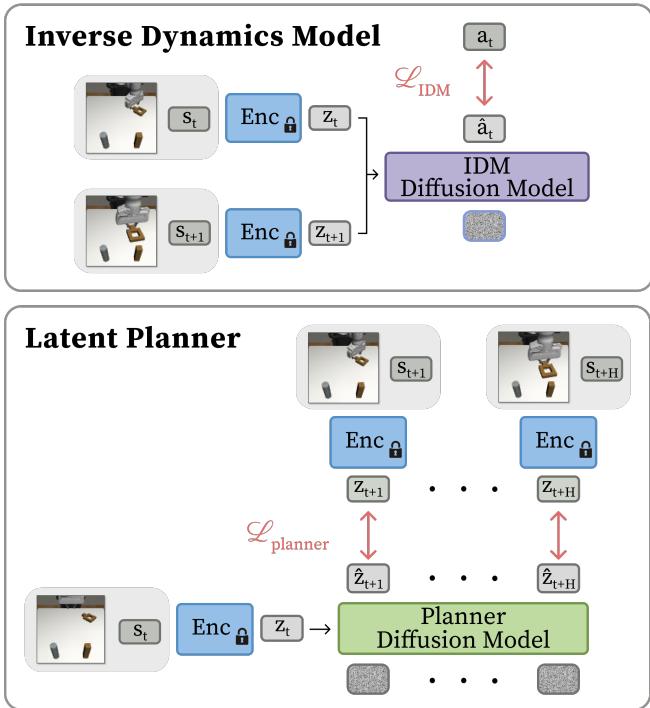

Once the VAE is trained, we freeze it. We no longer care about pixels; we only care about the latent vectors \(z\). The Planner is a diffusion model tasked with “imagining” the future.

Given the current latent state \(z_k\), the planner predicts a sequence of future latent states: \(\hat{z}_{k+1}, \dots, \hat{z}_{k+H}\).

As shown in the bottom half of Figure 2, the planner uses a Conditional U-Net architecture (adapted from Diffusion Policy). It starts with Gaussian noise and denoises it into a coherent trajectory of latent embeddings.

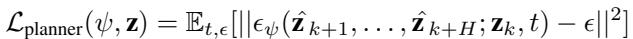

The loss function for the planner is:

Why is this powerful? This objective relies only on states (\(\mathbf{z}\)). This means you can feed the planner video demonstrations where no action data was recorded. The planner learns “If I am holding the cup, the next valid state is the cup being slightly higher,” without needing to know the motor currents required to lift it.

3. The Inverse Dynamics Model (IDM)

The planner gives us a “mental movie” of success, but the robot needs motor commands. This is the job of the Inverse Dynamics Model (IDM).

The IDM is a smaller diffusion model that takes two adjacent latent states, \(z_k\) and \(z_{k+1}\), and predicts the action \(a_k\) required to bridge the gap.

The loss function is straightforward:

Why is this powerful? The IDM learns local physics. Even in a “failed” trajectory where the robot knocks a cup over (suboptimal data), the transition from [hand near cup] to [hand hitting cup] contains valid physics about how the arm moves. The IDM can learn from this messy data, whereas a standard behavioral cloner would be confused by the failure.

The Inference Loop

During deployment (runtime), LDP executes a closed-loop cycle:

- Observe: The robot sees the current image \(x_0\) and encodes it into \(z_0\).

- Plan: The Planner diffuses a sequence of future latents \(\hat{z}_1 \dots \hat{z}_H\).

- Act: The IDM looks at the pairs \((z_0, \hat{z}_1), (\hat{z}_1, \hat{z}_2) \dots\) and predicts the corresponding actions.

- Execute: The robot executes a chunk of these actions (Receding Horizon Control), then observes the new state and replans.

This approach is closed-loop. Unlike some video planners that generate a long video once and blindly follow it, LDP replans at every step (or every few steps), allowing it to correct mistakes if the robot slips or is pushed.

Experiments and Results

The researchers evaluated LDP on several challenging simulated tasks (Robomimic Lift, Can, Square, and ALOHA Transfer Cube) and a real-world Franka Emika Panda arm task. The primary goal was to see if LDP could actually utilize “junk” data to improve performance.

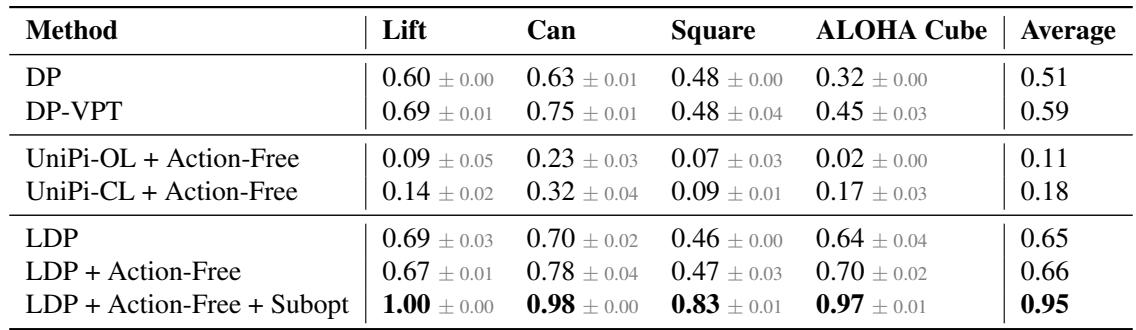

Leveraging Action-Free Data

First, they tested a “low-data” regime where they only provided a small number of expert demonstrations. They then added action-free data (videos of the task with no action labels).

The baselines included:

- DP (Diffusion Policy): Standard SOTA, can’t use action-free data.

- DP-VPT: A method that tries to label the action-free data using a separate model, then trains DP on it.

- UniPi: A video-based planner that generates pixels rather than latents.

Table 1 Analysis:

- LDP outperforms UniPi: The pixel-based planners (UniPi-OL and UniPi-CL) struggle significantly, achieving success rates below 20% on difficult tasks like Square and Cube. Planning in pixel space is simply too hard and error-prone.

- LDP vs. Labeling (DP-VPT): While using a model to pseudo-label data (DP-VPT) helps, LDP performs better (Average 0.65 vs 0.59). This suggests that letting the planner simply learn state transitions is more robust than trying to guess exact actions for the training set.

- The “Synergy” Effect: The last row shows LDP using both action-free and suboptimal data, achieving a massive jump to 0.95 average success. This confirms that the modular components feed into each other: better planning from videos + better physics understanding from suboptimal logs.

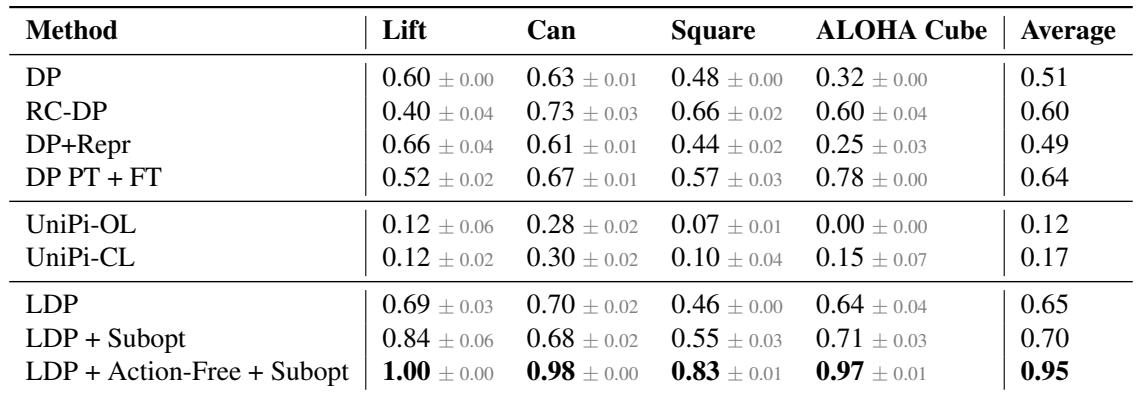

Leveraging Suboptimal Data

Next, they looked at suboptimal data—failed trajectories. Standard Imitation Learning assumes the demonstrator is an expert. If you clone a failure, you fail.

LDP uses this data to train the IDM (learning how actions affect states) and the VAE (learning to represent the world), even if the trajectory failed to reach the goal.

Table 2 Analysis:

- LDP dominates: Comparing standard DP (0.51) to LDP + Subopt (0.70) shows a clear benefit. The modular design allows LDP to extract value from failures.

- Comparison to Reward-Conditioned DP (RC-DP): RC-DP is a technique that tells the policy “this is a bad trajectory” or “this is a good trajectory.” While RC-DP improves over the baseline (0.60), LDP still outperforms it, particularly on the complex “ALOHA Cube” task.

- Video Planning Struggles: Again, UniPi (both open-loop and closed-loop) fails to gain traction here, highlighting the efficiency of the latent space planning over pixel space planning.

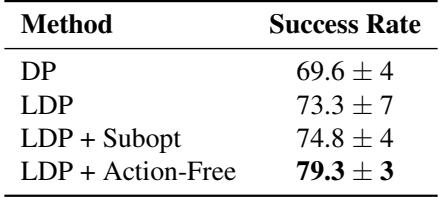

Real-World Performance

Simulations are useful, but the real test is physical hardware. The team set up a Franka arm task involving lifting a cube.

Table 3 Analysis: The real-world results mirror the simulation. LDP trained with additional suboptimal and action-free data reaches nearly 80% success, roughly 10 percentage points higher than the standard Diffusion Policy. This is a critical margin in robotics, where reliability is everything.

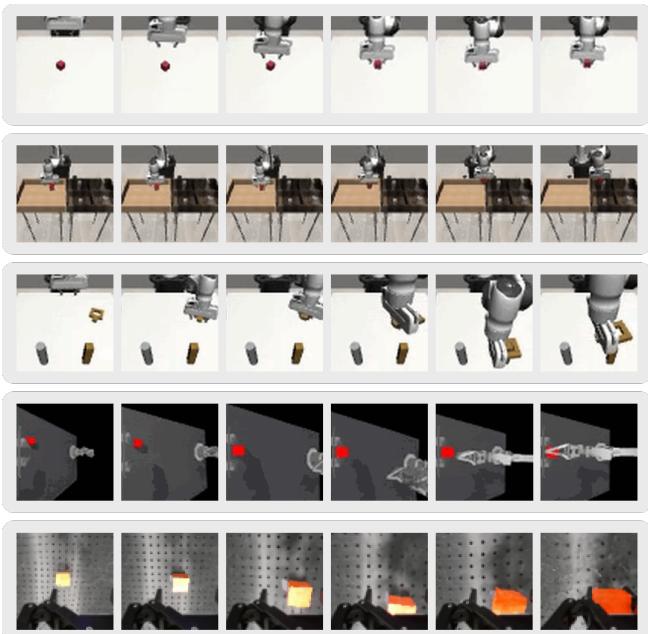

Visualizing the “Mind” of the Robot

One of the coolest aspects of LDP is that we can actually visualize what the robot is thinking. By taking the forecasted latent vectors \(\hat{z}\) and passing them back through the VAE decoder, we can see the “imagined” future states.

In Figure 3, you can see the dense plans generated by the model.

- Row 1 (Lift): The model imagines the gripper moving down, grasping the red square, and lifting.

- Row 3 (Square): You can see the manipulation of the nut onto the peg.

This confirms that the diffusion planner isn’t just hallucinating numbers; it has learned a structured, physical understanding of how the task progresses over time.

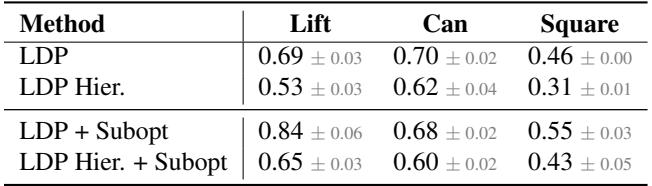

Ablation: Dense vs. Hierarchical Planning

Finally, the authors checked if “Dense” forecasting (predicting every step) was necessary. Could we just predict “waypoints” (subgoals) further apart?

Table 4 shows that Dense Forecasting (LDP) significantly outperforms Hierarchical (waypoint-based) planning.

- Why? In complex manipulation, the transition matters. If you only predict the end state, the robot might try to teleport the arm through an obstacle or miss a grasp because it didn’t plan the approach angle. Predicting the dense sequence acts as a guide rail for the entire motion.

Conclusion and Implications

Latent Diffusion Planning offers a compelling new recipe for robot learning. By decoupling planning from action execution, it breaks the strict dependency on expensive, expert-labeled data.

Key Takeaways:

- Don’t throw away “junk” data: LDP turns failed rollouts and action-free videos into valuable training signals.

- Plan in Latents, not Pixels: Compressing images via VAE makes the diffusion planning process faster and more accurate than video generation methods.

- Modular is Robust: Separating the planner and the IDM allows each component to specialize, leading to closed-loop policies that are reactive and reliable.

For students and researchers entering the field, LDP highlights a broader trend: the future of robotics likely isn’t just about better algorithms for expert data, but about architectures that can ingest the messy, unstructured, and massive datasets that already exist in the world. As we look toward scaling up robotic foundation models, techniques like LDP that can learn from the “entire internet” of video data will be essential.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2504.16925/images/cover.png)