Introduction

In the evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, computer vision models have achieved superhuman performance in tasks ranging from medical diagnosis to autonomous driving. However, these models possess a startling vulnerability: adversarial examples.

Imagine taking a photo of a panda, adding a layer of static noise imperceptible to the human eye, and feeding it to a state-of-the-art AI. Suddenly, the AI is 100% convinced the panda is a gibbon. This is not a hypothetical scenario; it is the fundamental premise of adversarial attacks. These perturbations are designed to exploit the specific mathematical sensitivities of neural networks, causing catastrophic failures in classification.

To counter this, researchers have developed Adversarial Purification. The idea is elegant in its simplicity: before an image is fed into a classifier, it passes through a “purifier” model designed to wash away the adversarial noise, restoring the image to its clean state. Recently, diffusion models—the same technology behind image generators like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion—have become the gold standard for this task. They add noise to the image until the adversarial patterns are drowned out, and then reconstruct the image from scratch.

However, there is a catch. Current diffusion-based purification methods often throw the baby out with the bathwater. In the process of scrubbing away the adversarial noise, they frequently destroy the semantic content (the actual “panda-ness”) of the image.

In this deep dive, we will explore a groundbreaking paper titled “Diffusion-based Adversarial Purification from the Perspective of the Frequency Domain.” The researchers propose a novel method, FreqPure, that fundamentally changes how we approach image purification. By analyzing images not just as pixels, but as waves in the frequency domain, they have found a way to remove the attack while preserving the soul of the image.

Background: The Battle for Robustness

Before dissecting the solution, we must understand the battlefield.

The Problem with Pixels

Standard computer vision models look at images as grids of pixels (spatial domain). Adversarial attacks manipulate these pixel values slightly. Defenses like Adversarial Training involve showing the model millions of attacked images during training so it learns to ignore them. While effective, this is computationally expensive and hard to generalize to new types of attacks.

Adversarial Purification is different. It is a pre-processing step. It doesn’t require retraining the classifier. It simply takes an input \(\mathbf{x}_{adv}\) and tries to transform it back to the original \(\mathbf{x}_{0}\).

Diffusion Models as Purifiers

Diffusion models work in two steps:

- Forward Process: Gradually add Gaussian noise to an image until it becomes pure random static.

- Reverse Process: Learn to subtract that noise step-by-step to recover a clean image.

For purification, we take an attacked image, add a little bit of noise (diffuse it partially), and then run the reverse process. The theory is that the adversarial perturbations—being fragile and specific—will be destroyed by the added noise, while the robust features of the image remain, allowing the reverse process to reconstruct a clean version.

The Flaw: The researchers of this paper argue that existing methods are too aggressive. They treat the whole image as a single entity to be denoised, failing to distinguish between the parts of the image that are actually attacked and the parts that are safe.

The Frequency Domain Perspective

To solve this, the authors turn to the Frequency Domain. Using the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), any image can be decomposed into sine and cosine waves of different frequencies. This transformation breaks an image into two components:

- Amplitude Spectrum: Represents the intensity or strength of different frequencies. It generally dictates the “style” and contrast of the image.

- Phase Spectrum: Represents the shift of the waves. It carries the crucial structural information—edges, shapes, and object boundaries.

Analyzing the Damage

The researchers asked a pivotal question: How do adversarial attacks affect the frequency components of an image?

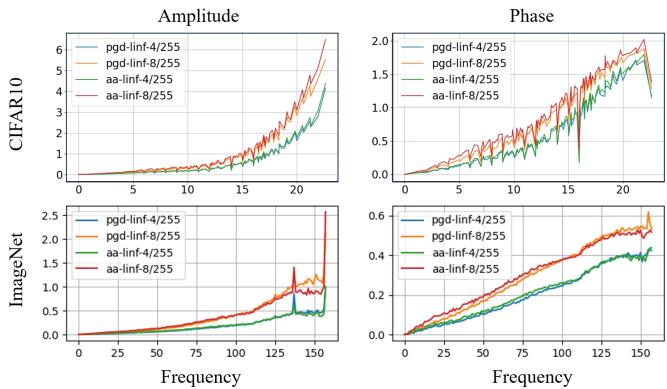

They analyzed datasets like CIFAR-10 and ImageNet under various attacks (like PGD and AutoAttack) and visualized the difference between clean images and attacked images across the frequency spectrum.

Figure 1 above illustrates their findings. The x-axis represents frequency (low to high), and the y-axis represents the difference between the clean and adversarial images.

The Key Insight: For both the amplitude (left) and phase (right), the damage caused by adversarial perturbations increases monotonically with frequency.

- Low Frequencies (Left side of graphs): The difference is near zero. This means the general structure, color, and lighting of the adversarial image are almost identical to the original.

- High Frequencies (Right side of graphs): The difference spikes. This confirms that adversarial noise hides primarily in the high-frequency details (rapid changes in pixel values).

Theoretical Proof of Over-Destruction

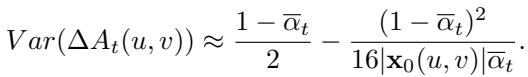

While the empirical data shows that low frequencies remain relatively clean in adversarial images, the authors theoretically prove that standard diffusion purification destroys everything.

They derived the variance of the difference in amplitude (\(\Delta A_t\)) and phase (\(\Delta \theta_t\)) between the clean image and the noisy image during the diffusion process.

As the diffusion timestep \(t\) increases (meaning we add more noise to purify the image), the variance in both equations increases.

What does this mean? It means that standard diffusion-based purification indiscriminately corrupts the low-frequency information—the very information that Figure 1 showed was actually safe! By blindly diffusing the image, traditional methods destroy the valid content and structure of the image, making the reconstruction job much harder and less accurate.

The Core Method: FreqPure

Based on these insights, the researchers propose FreqPure. The philosophy is simple: Don’t fix what isn’t broken.

Since the low-frequency components of the adversarial image are largely undamaged, the purification process should explicitly preserve them. FreqPure intervenes at every step of the reverse diffusion process to “correct” the estimated image using the low-frequency information from the input.

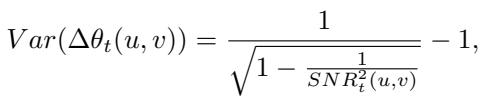

As shown in Figure 2, the pipeline works iteratively. At each timestep of the reverse diffusion:

- The model predicts a “clean” image \(\mathbf{x}_{0|t}\) from the current noisy state.

- This estimate is converted to the frequency domain using DFT.

- Two parallel operations occur: Amplitude Spectrum Exchange and Phase Spectrum Projection.

- The corrected frequency components are converted back to the spatial domain using inverse DFT (iDFT) to guide the next sampling step.

Let’s break down the two core mechanisms.

1. Amplitude Spectrum Exchange (ASE)

The amplitude spectrum of natural images typically follows a power law—low frequencies contain most of the energy. The experiments showed these low-frequency amplitudes are robust against attacks.

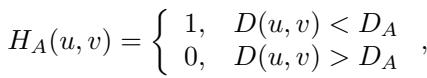

Therefore, the authors construct a low-pass filter mask, \(H_A\). This mask is 1 for low frequencies (center of the spectrum) and 0 for high frequencies.

They then update the estimated image’s amplitude (\(\hat{A}_{\mathbf{x}_{0|t}}\)) by mixing it with the adversarial input’s amplitude (\(A_{\mathbf{x}_0}\)—note that in purification context, \(\mathbf{x}_0\) refers to the input image, i.e., the adversarial one).

In plain English: “Take the low-frequency amplitude from the input image (because we trust it) and combine it with the high-frequency amplitude from the diffusion model’s estimate (because the input’s high frequencies are corrupted).”

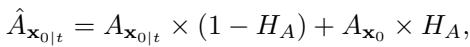

2. Phase Spectrum Projection (PSP)

The phase spectrum is trickier. It dictates the structure (where things are). While low-frequency phase is less affected by attacks than high-frequency phase, it isn’t perfectly untouched. Directly copying the phase from the adversarial image might leak some adversarial patterns or create artifacts because phase is very sensitive.

Instead of a direct swap, the authors use Projection. They define a “safe region” around the low-frequency phase of the adversarial input. If the diffusion model’s estimated phase falls outside this region, it is projected back into it.

Here, \(\Pi\) represents the projection operation, and \(\delta\) defines the allowable range of variation.

In plain English: “We know the true structure is somewhat close to the adversarial image’s low-frequency structure. Let the diffusion model generate the structure, but if it drifts too far away from the input’s low-frequency phase, nudge it back closer.”

This allows the method to extract coarse-grained structural information from the input while still allowing the diffusion model to fix the fine details.

Experiments and Results

The researchers evaluated FreqPure against state-of-the-art defenses (like DiffPure, GDP, and AT) on benchmark datasets CIFAR-10 and ImageNet. They used strong attacks like PGD and AutoAttack.

Quantitative Success

The results were highly promising. The method consistently outperformed existing purification techniques in both Standard Accuracy (performance on clean images) and Robust Accuracy (performance on attacked images).

CIFAR-10 Results

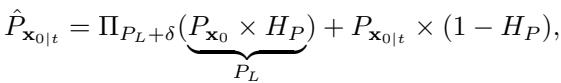

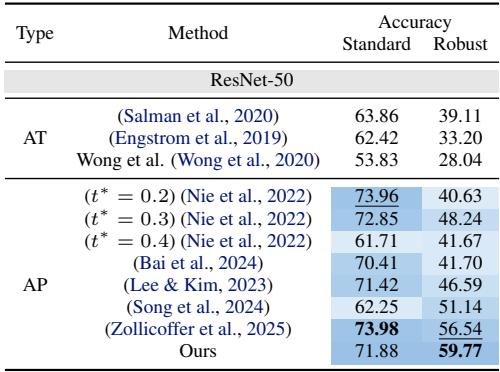

Looking at Table 1 (using WideResNet-28-10):

- Standard Accuracy: FreqPure achieves 92.19%, significantly higher than DiffPure (90.07%) and comparable to the best adversarial training methods. This proves that preserving low frequencies keeps the image content intact.

- Robust Accuracy (AutoAttack): It reaches 77.35%, outperforming standard Adversarial Training and other purification methods.

ImageNet Results

On the much harder ImageNet dataset (Table 6), the gap widens. FreqPure achieves a Robust Accuracy of 59.77%, whereas DiffPure sits at around 40-48% depending on the noise level. This is a massive improvement, highlighting the scalability of the frequency-based approach.

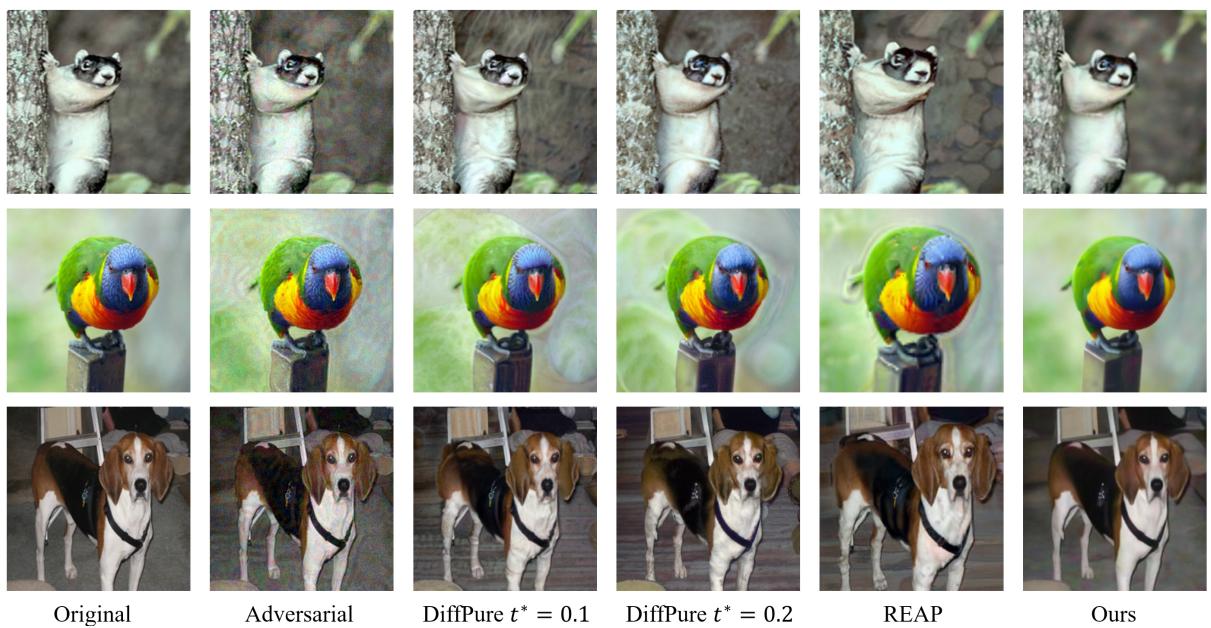

Qualitative Analysis: Seeing is Believing

Numbers are great, but in computer vision, we want to see the results. Does the purified image actually look like the original?

Figure 3 shows a comparison between the original clean image, the adversarial image, and the outputs of various purification methods (DiffPure, REAP, and Ours/FreqPure).

- DiffPure: Often leaves the image blurry or introduces color shifts (look at the lemur’s fur or the bird’s feathers). This is the “over-washing” effect of damaging low frequencies.

- FreqPure (Ours): The images are sharp, and the colors are vibrant and accurate to the original. The texture of the lemur and the patterns on the bird are preserved beautifully.

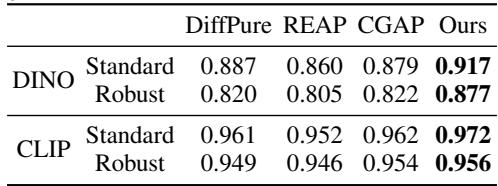

Similarity Metrics

To quantify “similarity,” the authors used advanced perceptual metrics like DINO and CLIP scores, which measure how semantically similar two images are.

As shown in Table 7, FreqPure achieves the highest similarity scores across the board. This confirms mathematically what our eyes saw in Figure 3: FreqPure produces images that are most faithful to the original content.

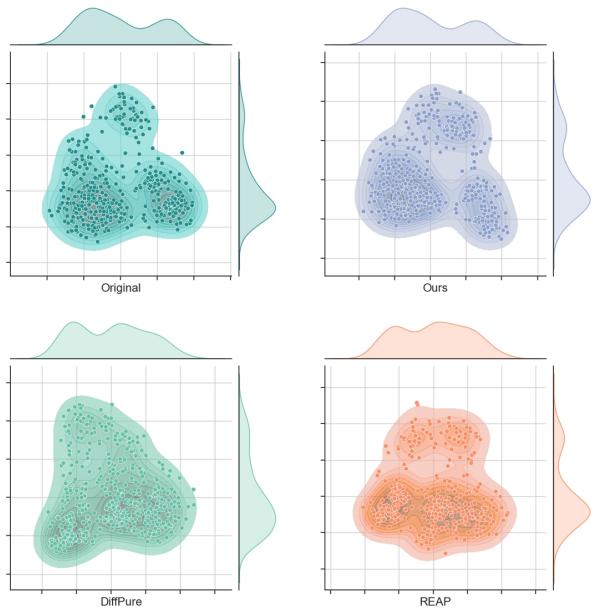

Statistical Distributions

Finally, the authors plotted the joint distribution of the purified images versus the original images. Ideally, these distributions should overlap perfectly.

Figure 4 demonstrates this clearly. The plot for “Ours” (Top Right) shows a distribution that is tight and structurally very similar to the “Original” (Top Left). In contrast, DiffPure (Bottom Left) and REAP (Bottom Right) show more dispersed or shifted distributions, indicating a loss of information or introduction of artifacts.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Diffusion-based Adversarial Purification from the Perspective of the Frequency Domain” offers a compelling lesson in machine learning: sometimes, looking at data from a different angle (quite literally, the frequency domain) reveals simple solutions to complex problems.

By recognizing that adversarial attacks disproportionately affect high frequencies, the authors identified a major inefficiency in existing diffusion defenses—they were destroying safe, low-frequency data. The FreqPure method fixes this by acting as a frequency-selective filter during the generation process.

Key Takeaways:

- Adversarial Noise is High-Frequency: The content and structure (low frequency) of an attacked image are usually trustworthy.

- Standard Diffusion is Indiscriminate: It erodes all frequencies over time, reducing accuracy.

- Guided Purification Works: By swapping amplitudes and projecting phases in the low-frequency range, we can guide the diffusion model to restore high-frequency details without hallucinating or blurring the main subject.

This work not only sets a new benchmark for adversarial robustness but also bridges the gap between classical signal processing and modern generative AI. It suggests that the future of robust AI might lie in hybrid approaches that combine the generative power of neural networks with the mathematical precision of frequency analysis.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2505.01267/images/cover.png)