Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence, a critical question arises every time a new Large Language Model (LLM) is released: Is it better than the rest?

To answer this, the community has turned to “Model Arenas.” Platforms like Chatbot Arena allow users to prompt two anonymous models simultaneously and vote on which response is better. It is a digital colosseum where models battle for supremacy. To quantify these wins and losses into a leaderboard, researchers rely on the ELO rating system—the same algorithm used to rank chess players and video game competitors.

However, applying a system designed for chess to LLMs brings significant problems. Standard ELO ratings are notoriously unstable when applied to crowdsourced data. They fluctuate based on the order in which battles occur, and perhaps more importantly, they treat every human voter as equally competent. Whether the annotator is a domain expert or someone clicking randomly, the ELO algorithm treats their vote with the same weight.

In this deep dive, we will explore a new research paper that proposes a solution: the Stable Arena Framework. We will break down how the researchers replaced the unstable, iterative nature of standard ELO with a robust statistical approach called m-ELO, and how they further upgraded it to am-ELO—a system that not only ranks the models but also judges the judges.

The Problem with Current Arenas

Before understanding the solution, we must understand why the current system is flawed.

The standard ELO system updates a model’s score iteratively. After every battle, the winner gains points and the loser drops points. The amount of points exchanged depends on the difference in their current ratings.

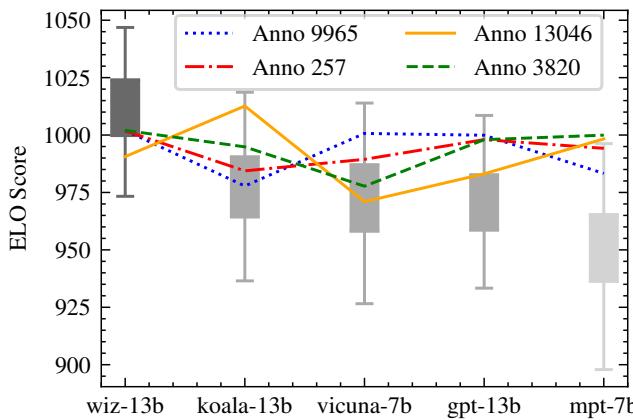

As shown in Figure 1, standard ELO scores can be highly volatile. The graph displays score fluctuations for models like vicuna-7b and koala-13b. The significant error bars and the “jumping” lines indicate that the calculated score depends heavily on when the calculation happens and the specific sequence of records.

There are two main culprits for this instability:

- Order Sensitivity: ELO is a dynamic algorithm. If you shuffle the history of battles and re-run the calculation, you often get different final scores.

- Annotator Variance: Human evaluation is subjective. One person might value code accuracy, while another values polite tone. Worse, some annotators might be spammers or bots. The standard ELO system ignores these individual differences, assuming a “perfectly average” human in every interaction.

The Foundation: The Classic ELO Update

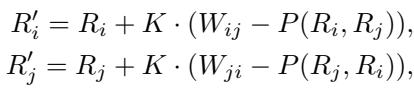

To fix ELO, we first need to look at its mathematical engine. In the traditional system, when model \(i\) fights model \(j\), we update their scores (\(R\)) using the following formula:

Here, \(K\) is a scaling factor (how fast scores change), and \(P(R_i, R_j)\) is the expected probability of model \(i\) winning. The system looks at the difference between the actual result \(W_{ij}\) (1 for a win, 0 for a loss) and the expected probability.

This method works well for sequential sports games, but in LLM evaluation, we often have a static dataset of thousands of past battles. Treating this static data as a sequential stream introduces artificial “time” dependency, leading to the instability we saw in Figure 1.

The Solution Part 1: m-ELO (Maximum Likelihood Estimation)

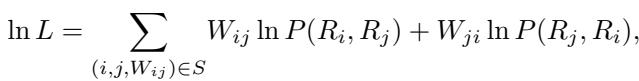

The researchers propose a shift from iterative updates to global optimization. Instead of updating scores one game at a time, why not look at the entire history of battles and find the set of scores that best explains the data?

This approach is called m-ELO. It uses Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) to find the model ratings.

The logic is captured in this log-likelihood function:

In simple terms, this equation calculates how likely the observed wins and losses are, given a specific set of model scores. The goal is to maximize this value. By using gradient descent to solve this equation, the result becomes order-independent. You can shuffle the battle records however you like; the m-ELO approach will converge to the same rating.

This solves the first problem (instability due to order), but it doesn’t solve the second problem: the unreliability of human annotators.

The Solution Part 2: am-ELO (Annotator Modeling)

The most significant contribution of this paper is am-ELO. The researchers drew inspiration from Item Response Theory (IRT) in psychometrics, which is used to grade tests while accounting for question difficulty and student ability.

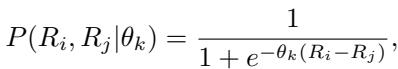

In the context of an Arena, the researchers realized they could model the ability of the annotator (\(\theta_k\)).

The Intuition

In standard ELO, there is a constant parameter usually denoted as \(C\) (or embedded in the logistic function) that dictates how much a difference in skill affects the win probability. The researchers realized this shouldn’t be a constant.

- If an annotator is an expert ($ \theta $ is high), they can easily distinguish between a slightly better model and a slightly worse one.

- If an annotator is random or confused ($ \theta $ is near 0), their votes don’t correlate well with the true difference in model quality.

- If an annotator is malicious or biased ($ \theta $ is negative), they might consistently vote for the worse model.

The New Probability Function

The researchers modified the probability function to include this new parameter \(\theta_k\) for each specific annotator \(k\):

This small change is profound. It means the expected probability of a win depends not just on the models’ skill difference (\(R_i - R_j\)), but also on the annotator’s reliability (\(\theta_k\)).

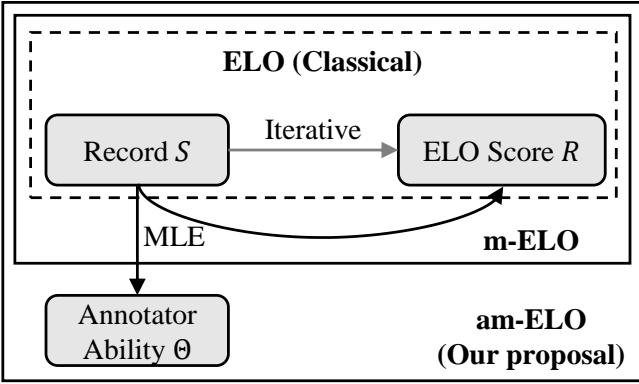

The Architecture Comparison

We can visualize the difference between the traditional approach and this new framework below:

As shown in Figure 2, the classical method (top) cycles purely between records and scores. The new am-ELO method (bottom) takes a holistic view, feeding records and scores into a Maximum Likelihood Estimation engine that outputs both Model Scores and Annotator Abilities simultaneously.

Optimization

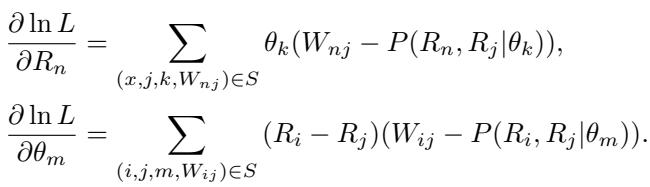

To train this system, the researchers use gradient descent to update both the model ratings (\(R\)) and the annotator parameters (\(\theta\)). The gradients look like this:

The top equation updates the model’s score based on whether it won or lost, weighted by the annotator’s reliability (\(\theta_k\)). The bottom equation updates the annotator’s reliability based on whether their vote aligned with the consensus ranking of the models (\(R_i - R_j\)).

This creates a virtuous cycle: Better model rankings help identify good annotators, and good annotators help refine model rankings.

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested their framework on the Chatbot Arena dataset, containing 33,000 conversations and votes.

1. Better Fit and Prediction

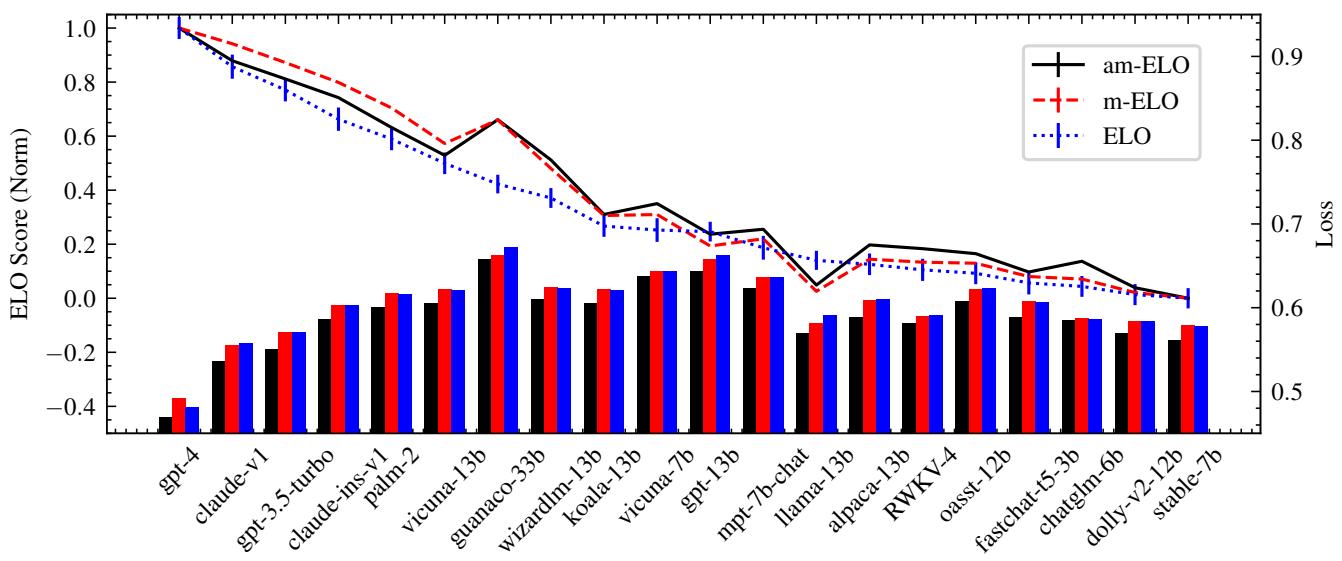

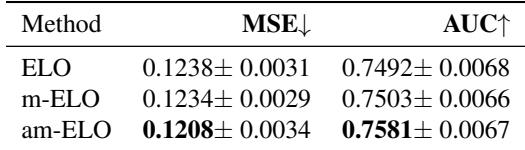

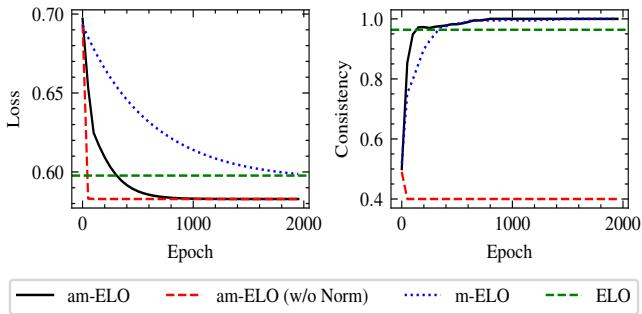

First, they checked how well the different methods fit the data. A lower “Loss” means the model explains the reality of the battles better.

In Figure 3, the bar chart on the right shows the Loss. You can see that am-ELO (black line) achieves a significantly lower loss than standard ELO (blue) or m-ELO (red). This proves that accounting for annotator variance provides a much more accurate mathematical model of the arena.

Furthermore, Table 2 (below) shows that am-ELO is better at predicting the outcome of unseen battles (higher AUC and lower Mean Squared Error).

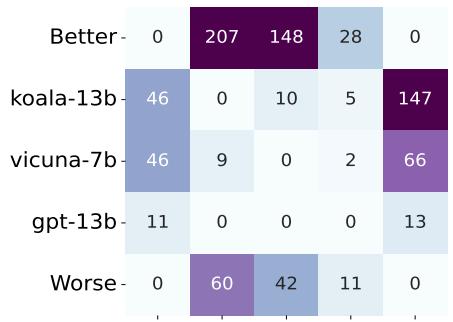

2. Correcting Rankings: The Case of Vicuna vs. Koala

One of the most interesting findings was how am-ELO corrected specific ranking errors. In the standard ELO system, a model named koala-13b was ranked higher than vicuna-7b. However, many in the community felt Vicuna was the stronger model.

Why did standard ELO get it wrong?

Figure 4 reveals the truth. koala-13b racked up many wins against “Worse” models (weak opponents). vicuna-7b fought fewer weak opponents but held its own against “Better” models.

Standard ELO blindly rewards accumulating wins. am-ELO, by considering the global context and annotator quality, correctly identified that vicuna-7b was actually the stronger model, adjusting the leaderboard to match human intuition.

3. Stability and Convergence

The “Stable” in Stable Arena Framework isn’t just a name. The researchers tracked how consistent the rankings were during the training process.

Figure 5 shows the consistency (right graph). The am-ELO method (solid black line) starts with low consistency but rapidly climbs to near 1.0. This indicates that the method reliably converges to the same set of scores, regardless of initialization. Note the dashed red line (am-ELO w/o Norm); without normalizing the sum of annotator abilities, the system becomes unstable, proving that normalization is a crucial step in the algorithm.

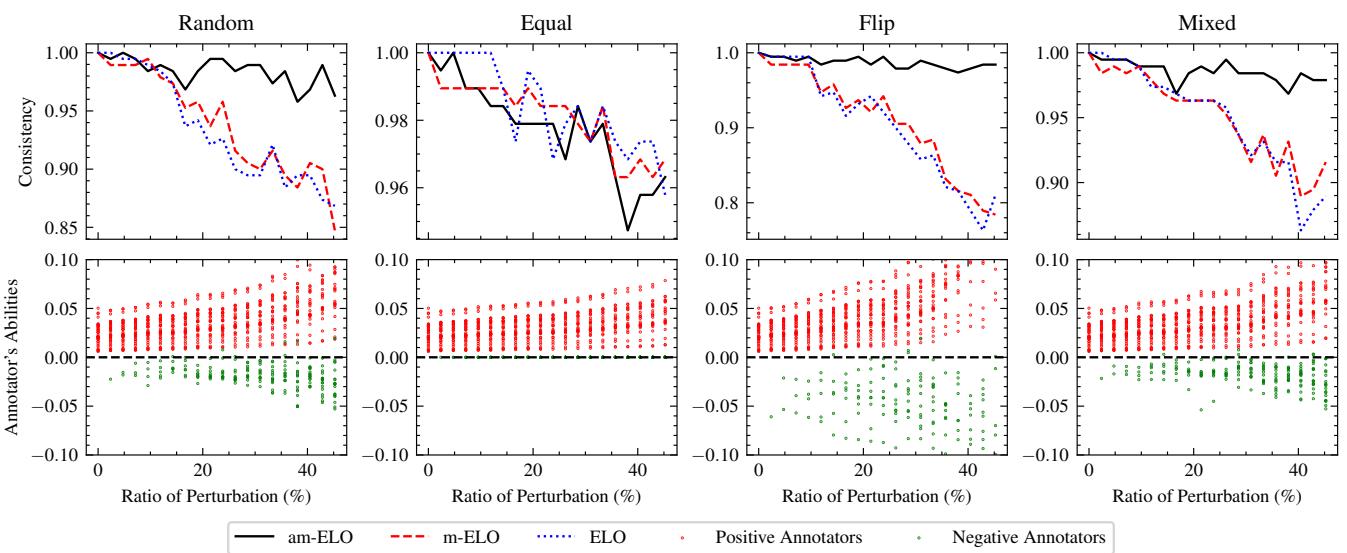

4. Detecting Malicious Annotators

Finally, the researchers simulated “attacks” on the arena. They introduced virtual annotators who would randomly flip votes, vote for the tie, or try to reverse the rankings.

Figure 6 demonstrates the robustness of the system.

- Top graphs (Consistency): Even as the ratio of bad annotators (perturbation) increases, am-ELO (black line) maintains high ranking consistency compared to standard ELO (blue dotted line).

- Bottom graphs (Annotator Ability): The red dots represent normal annotators, and the green dots represent the simulated attackers. Notice how the green dots plummet below zero? The am-ELO system successfully identified the attackers and assigned them negative capability scores, effectively neutralizing their malicious votes.

Conclusion

The “Stable Arena Framework” represents a significant maturation in how we evaluate AI. As Large Language Models become more integrated into society, the metrics we use to judge them must be rigorous.

By moving from simple iterative updates to a Maximum Likelihood Estimation approach (m-ELO), we solve the problem of order sensitivity. by integrating psychometric principles to model the judges themselves (am-ELO), we solve the problem of human variability.

This framework allows for a fairer, more robust leaderboard where:

- Model rankings are stable and reproducible.

- Annotator reliability is transparent, allowing platforms to reward good judges and filter out bad ones.

- Complex dynamics (like racking up wins against weak opponents) are handled intelligently.

For students and researchers entering the field of NLP evaluation, this paper serves as a perfect example of how borrowing mathematical tools from other fields (like psychometrics) can solve modern AI problems. The next time you see a leaderboard, remember: it’s not just about who wins the match, but who is watching the game.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2505.03475/images/cover.png)