In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence, a new and somewhat disturbing game of cat-and-mouse is emerging. We rely on Machine Learning (ML) models for high-stakes decisions—from approving loan applications to moderating hate speech on social media. Consequently, regulators and society at large demand that these models be “fair.” They should not discriminate based on gender, race, or age.

But here is the problem: How do you verify if a black-box model is fair?

Typically, an auditor sends a set of test queries to the model and checks the answers. But what if the model knows it is being tested? Much like the infamous “dieselgate” scandal where cars detected emissions tests and altered their performance, AI platforms can theoretically detect an audit and temporarily switch to a “fair” mode. This practice is known as fairwashing or audit manipulation.

In this deep dive, we will explore a fascinating research paper, “Robust ML Auditing using Prior Knowledge,” which proposes a mathematical and practical framework to catch these cheating models. We will walk through how fairwashing works, why standard audits fail, and how using “secret” prior knowledge can help auditors verify not just if a platform looks fair, but if it is actually honest.

The Problem: The Vulnerability of Black-Box Audits

To understand the solution, we first need to understand the vulnerability. Most third-party audits are “black-box” audits. The auditor does not see the code or the training data; they can only send inputs (\(X\)) and observe outputs (\(Y\)).

Current regulations generally require auditors to notify platforms before an audit occurs. This creates a massive loophole. A platform, motivated by profit or operational efficiency, might use a biased but highly accurate model for its day-to-day users. However, upon receiving the “audit set” (the list of questions from the regulator), the platform can seamlessly swap its behavior.

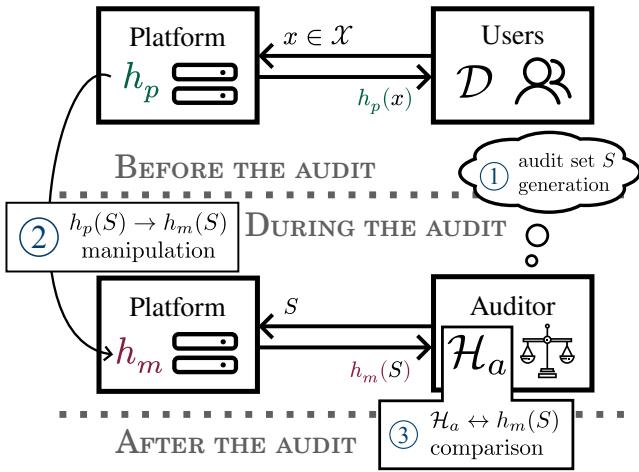

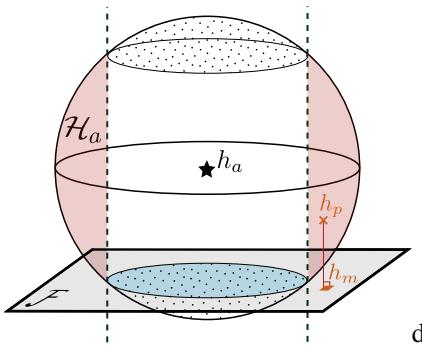

As illustrated in Figure 1, the process generally flows like this:

- Normal Operation: Users interact with the platform’s standard model, \(h_p\).

- The Audit: The auditor generates an audit dataset \(S\) and sends it to the platform.

- The Manipulation: The platform receives \(S\). Instead of answering truthfully with \(h_p\), it calculates a manipulated set of answers using a different logic, \(h_m\), specifically designed to look fair on the set \(S\).

- The Assessment: The auditor analyzes the manipulated answers \(h_m(S)\). If they look fair, the platform passes, even if it treats real users unfairly.

Defining Fairness: Demographic Parity

To make this concrete, let’s define what the auditor is usually looking for. One of the most common metrics is Demographic Parity (DP).

Demographic Parity essentially requires that a positive outcome (like getting a loan or having a post approved) should be given at the same rate to different groups (e.g., men vs. women), regardless of the input features.

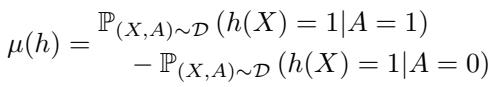

Mathematically, the metric \(\mu(h)\) represents the difference in probability of a positive outcome between two groups (where \(A=1\) is one group and \(A=0\) is the other):

If \(\mu(h) = 0\), the model is considered fair. The set of all fair models is denoted as \(\mathcal{F}\).

The problem is that DP is incredibly easy to manipulate. A platform doesn’t need to retrain its massive neural networks to pass a DP audit. It just needs to flip a few “No” decisions to “Yes” for the disadvantaged group within the audit dataset \(S\) until the numbers balance out.

The Solution: Auditing with Prior Knowledge

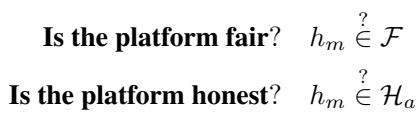

If a platform can manipulate its answers to appear fair, checking for fairness alone is insufficient. The auditor needs to check for two things simultaneously:

- Is the platform fair? (\(h_m \in \mathcal{F}\))

- Is the platform honest? Does the model they showed us (\(h_m\)) behave like a reasonable model for this task?

This second question is where Prior Knowledge comes in. The auditor needs an “Auditor Prior” (\(\mathcal{H}_a\))—a set of models that they expect to see.

If the platform returns a model \(h_m\) that is perfectly fair but makes bizarre predictions that no rational model would make (e.g., classifying a clear image of a cat as a dog just to balance a quota), the auditor should flag it as “dishonest.”

The Trap of Public Priors

A natural instinct for an auditor might be to use public data to build this prior knowledge. For example, if auditing a hate-speech detector, the auditor might download a public dataset like “Wikipedia Comments” and check if the platform’s model performs well on it.

However, the researchers prove a devastating theorem regarding public priors: If the auditor uses public knowledge, the platform can always cheat.

Theorem: If the platform knows the auditor’s prior (\(\mathcal{H}_a\)), it can simply find a model that sits in the intersection of “Fair Models” and “Expectable Models” (\(\mathcal{H}_a \cap \mathcal{F}\)).

Since the platform knows the public dataset, it can ensure its manipulated answers achieve high accuracy on that public dataset while also satisfying the fairness constraint. To the auditor, the model looks fair and accurate. The platform wins.

The Power of Private Data

To defeat manipulation, the auditor must possess private knowledge—specifically, a labeled dataset \(D_a\) that the platform has never seen and cannot predict.

Using this private dataset, the auditor defines the “Set of Expectable Models” (\(\mathcal{H}_a\)) as follows:

In simple terms: \(\mathcal{H}_a\) contains all models that have an error rate (loss \(L\)) lower than a certain threshold \(\tau\) on the auditor’s private dataset.

If the platform sends back answers (\(h_m\)) that have a high error rate on the auditor’s private data (i.e., the loss is greater than \(\tau\)), the auditor knows something is fishy. The platform likely distorted its answers so much to fake fairness that the model no longer makes sense on real data.

Geometric Intuition: The Sphere and the Plane

This concept is best understood geometrically. Imagine the space of all possible machine learning models.

- The Fair Plane (\(\mathcal{F}\)): There is a specific slice (a hyperplane) of this space containing all models that satisfy Demographic Parity.

- The Expectable Sphere (\(\mathcal{H}_a\)): The auditor’s private dataset defines a “ball” or sphere. Any model inside this sphere is “good enough” or “expectable” because it has low error on the private data.

The honest model used by the platform, \(h_p\), is likely inside the Expectable Sphere (because it’s a good model) but not on the Fair Plane (because it’s biased).

Figure 2 above visualizes the trap.

- \(h_p\) (Honest Model): It sits inside the sphere but off the plane.

- \(h_m\) (Manipulated Model): The platform tries to move \(h_p\) onto the blue Fair Plane.

- The Trap: If the platform moves \(h_p\) to the blue plane, but that spot on the plane falls outside the sphere (into the red area), the auditor detects the manipulation! The model has become “unexpected” (too much error).

The platform wants to land in the blue shaded region (Fair AND Expectable). The auditor wins if the platform is forced into the red region (Fair but Suspicious).

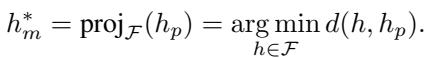

The Math of Optimal Manipulation

The platform is not acting randomly. It wants to pass the audit with the minimal amount of lying necessary. It wants to find a model \(h_m\) that is fair (\(\in \mathcal{F}\)) but stays as close as possible to its original behavior (\(h_p\)) to maintain plausibility.

This is an optimization problem. The “Optimal Manipulation” is the mathematical projection of the honest model onto the fair plane:

The platform calculates this \(h_m^*\) to send to the auditor.

Can the Auditor Catch Them?

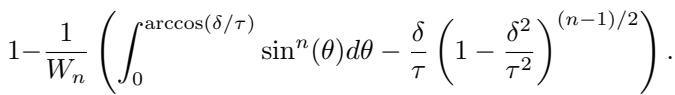

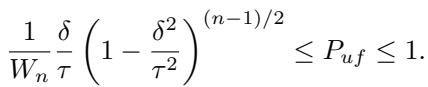

The core contribution of this paper is quantifying the probability of catching this optimal manipulation. This is called the Detection Rate (\(P_{uf}\)).

The detection depends on two critical distances:

- \(\delta\) (Delta): The “unfairness” of the ground truth. How far is the actual best possible model from the fair plane? If the real world is very biased (high \(\delta\)), the honest model is deep inside the sphere but far from the plane.

- \(\tau\) (Tau): The auditor’s tolerance. How large is the “Expectable Sphere”? A large \(\tau\) means the auditor accepts mediocre models. A small \(\tau\) means the auditor demands high accuracy.

The researchers derived a closed-form solution for the probability of detection using high-dimensional geometry (specifically utilizing Wallis’ integrals).

While the formula looks intimidating, the intuition is elegant. It calculates the volume of the “cap” of the sphere that intersects with the fair plane. If that intersection is small, the probability of the platform landing safely inside it is low.

A simplified lower bound for this probability is given by:

Key Takeaway from the Math:

- If \(\tau \approx \delta\) (the auditor is very strict and the radius of the sphere is barely larger than the distance to the fair plane), the detection probability goes to 1. The platform has no room to hide.

- If \(\tau\) is large (the auditor is lenient), the detection probability drops. The platform has plenty of space to find a model that is both fair and “good enough.”

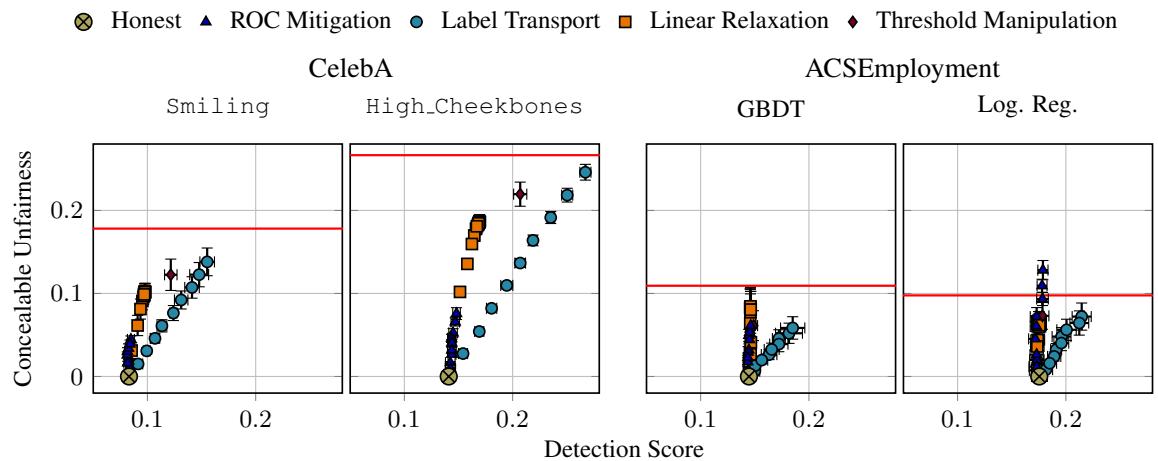

Experimental Reality: How Much Can They Hide?

The theory is sound, but does it hold up against real data? The researchers tested this framework using two datasets:

- CelebA: A computer vision dataset of celebrity faces (predicting attributes like “Smiling” or “High Cheekbones”).

- ACSEmployment: A tabular dataset predicting employment status based on census data.

They simulated a platform using sophisticated manipulation strategies (like “ROC Mitigation” and “Label Transport”) to fake fairness.

The Concept of “Concealable Unfairness”

The researchers measured Concealable Unfairness: The maximum amount of bias a platform can hide before the auditor notices something is wrong (i.e., before the detection score crosses the threshold).

Figure 3 shows the results.

- The Y-axis is Concealable Unfairness.

- The X-axis is the Detection Score (the error on the auditor’s private data).

- The Red Line represents the unfairness of the original, honest model.

The verdict? Look at how high the curves go. For most datasets, the platform can hide all of its unfairness (the curves reach the red line) while keeping the detection score relatively low.

For example, in the “CelebA Smiling” graph (top left), the platform can fully hide the bias with a detection score around 0.13. If the auditor sets their threshold \(\tau\) higher than 0.13, the platform gets away with it completely.

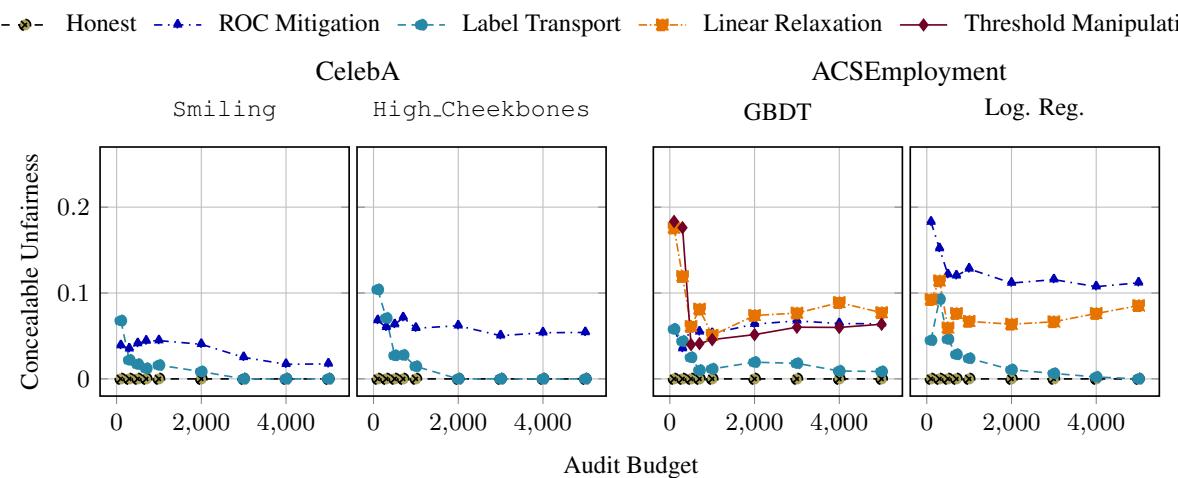

The “Audit Budget” Dilemma

One might assume that if the auditor just collects more data (increases the audit budget \(n\)), they will eventually catch the liar.

The researchers tested this by increasing the audit set size from 100 to 5,000 samples.

Figure 4 reveals a surprising nuance:

- Top Left (CelebA Smiling): As the budget increases, the concealable unfairness drops to zero. This is a success! The task is “easy” (low uncertainty), so the auditor can enforce a strict threshold.

- Top Right (CelebA High Cheekbones): The curve stays flat. Even with 5,000 samples, the platform can still hide significant unfairness.

Why? The “High Cheekbones” task is harder. State-of-the-art models have higher error rates naturally. This forces the auditor to use a looser threshold \(\tau\) (to avoid flagging honest but imperfect models). This looseness gives the malicious platform the “wiggle room” it needs to manipulate results, regardless of how much data the auditor uses.

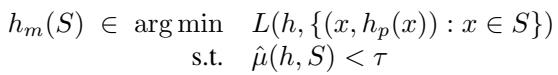

Implementing the Optimal Manipulation

It is worth noting how the platform cheats. The paper notes an irony: the techniques used to fake fairness are the exact same techniques developed by the scientific community to fix fairness.

The platform solves this optimization problem:

They use methods like ROC Mitigation or Linear Relaxation. In the experiments, the researchers found that these standard “fairness repair” tools were highly effective at deceiving the auditor when applied only to the audit set.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The paper “Robust ML Auditing using Prior Knowledge” serves as a wake-up call for AI governance. It demonstrates that naive, black-box auditing is fundamentally broken. If a platform knows it is being audited, it can almost always manipulate the results to appear fair.

Here are the critical takeaways for students and future practitioners:

- Public Benchmarks are unsafe for auditing: If the prior knowledge is public, the platform can game it. Theorem 3.2 proves this is a dead end.

- Private Data is essential: Auditors must maintain secret, high-quality labeled datasets (\(D_a\)) to verify platform honesty.

- The “Wiggle Room” of Uncertainty: The harder the ML task, the harder it is to audit. If a task has high natural error rates, auditors must be lenient, which inevitably allows platforms to hide bias.

- Geometry Matters: Understanding the geometric relationship between the “Fairness Plane” and the “Model Hypothesis Sphere” allows us to mathematically calculate the probability of catching a cheater.

As we move toward a world of enforced AI regulations (like the EU AI Act), this research highlights that auditing is not just a bureaucratic checkbox. It is an adversarial game. To ensure AI helps rather than harms, auditors need to be as sophisticated—and as well-equipped with data—as the models they oversee.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2505.04796/images/cover.png)