Code review is the gatekeeper of software quality. In a perfect world, a senior engineer meticulously checks every line of code you write, catching subtle logic errors, security vulnerabilities, and potential performance bottlenecks before they merge.

In the real world, code review is often a bottleneck. Reviewers are busy, context is hard to gather, and “LGTM” (Looks Good To Me) is sometimes typed a bit too quickly.

This has driven a massive surge in research into Automated Code Review. If an AI can write code, surely it can review it? However, most existing tools fall into a trap: they treat code review as a simple translation task. They look at a small snippet of code and try to generate a sentence that “sounds” like a review. The result? A flood of “nitpicks”—comments about variable naming or formatting—while critical bugs (like null pointer dereferences or logic errors) slip through.

Today, we are diving deep into a paper titled “Towards Practical Defect-Focused Automated Code Review”. This research moves beyond simple text generation. It details a system deployed in a massive tech company (serving 400 million daily users) designed to do one thing: find actual defects.

We will explore how the authors moved from “snippet-level” guessing to “repository-level” reasoning, using sophisticated techniques like code slicing, multi-role LLM agents, and a rigorous filtering pipeline.

The Core Problem: Why Current AI Reviewers Fail

To understand why this paper is significant, we first need to understand the limitations of the status quo.

Most academic research treats automated code review as a Code-to-Text problem. You feed a model a “diff” (the difference between the old and new code), and the model predicts a text sequence (the comment). These models are often evaluated using BLEU scores—a metric borrowed from machine translation that measures how much the generated text overlaps with a “reference” text.

This approach has three fatal flaws:

- Context Myopia: A standard “diff” only shows what changed. It doesn’t show where a variable was defined three files away, or how a function is used elsewhere. Without this context, finding deep logic bugs is impossible.

- Nitpick Overload: Because the models are trained on all historical data, they learn to replicate the most common comments: style suggestions. They hallucinate issues or complain about things that don’t matter (False Alarms).

- Wrong Metrics: A generic comment like “Please fix this logic” might get a high BLEU score because it matches the reference words, even if it offers no specific help. Conversely, a brilliant, novel bug find gets a score of zero because it wasn’t in the reference set.

The authors of this paper argue that the goal shouldn’t be “text similarity.” The goal should be Defect Detection.

The Real-World Pipeline

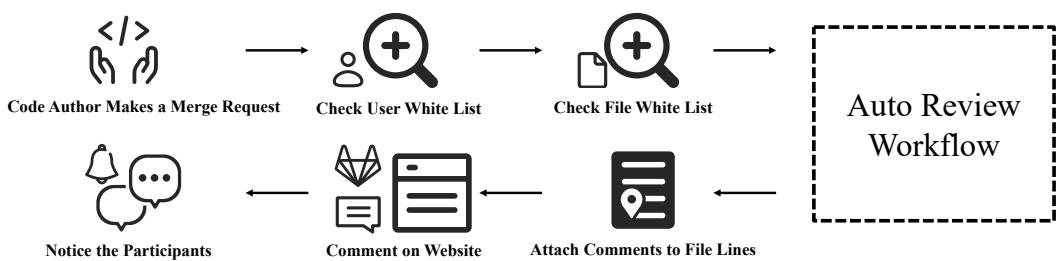

The researchers integrated their system into an industrial DevOps platform. This isn’t just a theoretical model; it sits right in the workflow between a developer making a Merge Request (MR) and the code being merged.

As shown in Figure 1, the pipeline is triggered by a merge request. It checks permissions, runs the automated review workflow, attaches comments to specific lines of code, and notifies the participants.

But what happens inside that dashed box labeled “Auto Review Workflow”? This is where the innovation lies. The authors identify four major challenges and propose a solution for each:

- Context: How do we feed the LLM the right code without exceeding its token limit? (Solution: Code Slicing)

- Accuracy: How do we find critical bugs? (Solution: Multi-Role System)

- Noise: How do we shut the AI up when it’s being annoying? (Solution: Filtering Mechanism)

- Usability: How do developers know where the bug is? (Solution: Line Localization)

Let’s break down the architecture.

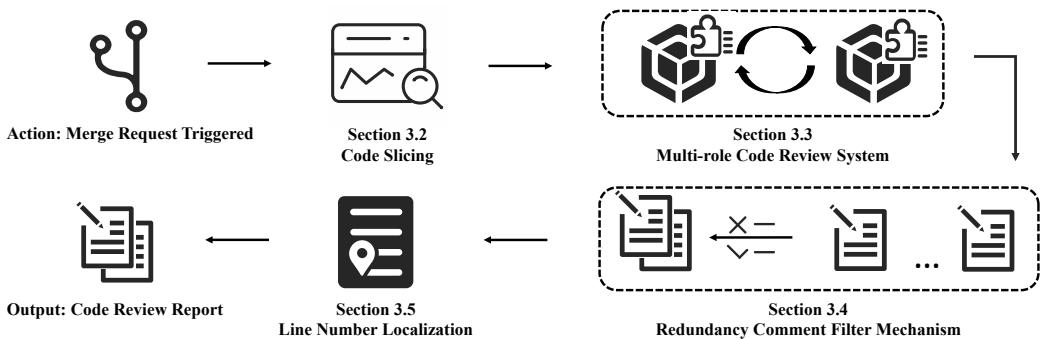

Figure 2 provides the high-level roadmap. The system takes the merge request, slices the code, passes it through a team of LLM agents, filters the results, and finally pins the comments to the exact line numbers.

Step 1: Code Slicing (Solving the Context Problem)

If you feed an LLM the entire repository, you run out of context window (and money). If you feed it just the changed lines, it lacks the information to find bugs. The middle ground is Code Slicing.

The authors propose four distinct slicing algorithms to gather context. Think of these as different “lenses” through which the AI views the code:

- Original Diff: The baseline. Just the raw changes. Good for syntax errors, bad for logic.

- Parent Function: Includes the entire function where the change happened. This helps the AI understand the immediate local logic.

- Left Flow: This is where it gets interesting. This algorithm performs static analysis to trace the “Left-Hand Values” (variables being assigned). It looks backwards to find where these variables came from and how they were defined.

- Full Flow: The most comprehensive method. It traces backwards (where variables came from) and forwards (how variables are used later, including function calls).

Why does this matter? Imagine you change x = y + 1.

- Original Diff sees just that line.

- Full Flow sees that

yis a pointer that might be null (defined 50 lines up) andxis used in a division later (potential divide-by-zero). This context is the difference between a nitpick and a bug catch.

Step 2: The Multi-Role Code Review System

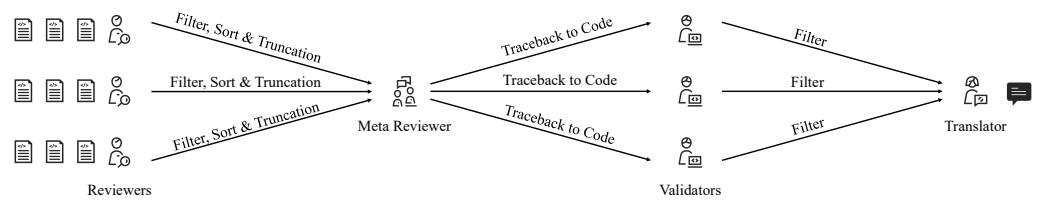

One prompt is rarely enough for complex reasoning. Inspired by “Agent” workflows, the authors devised a Multi-Role System. Instead of asking one AI to “review this code,” they assign specific personas to different instances of the model.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the workflow involves collaboration:

- The Reviewer: This agent looks at the sliced code and uses Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. It is asked to:

- Understand the change.

- Analyze for defects.

- Re-evaluate to check if it’s nitpicking.

- Output a draft comment.

- Note: The system can spawn multiple Reviewers to get different perspectives.

The Meta-Reviewer: If you have multiple Reviewers, they might duplicate work. The Meta-Reviewer acts as a manager. It aggregates comments, merges duplicates, and sorts them by severity.

The Validator: This is the quality control gate. It takes the merged comments and the code, and asks a critical question: “Is this comment actually correct?” It re-scores the issues to filter out hallucinations (fake bugs).

The Translator: Finally, for multinational teams, this role ensures the comment is in the correct language and formatted as JSON for the system to read.

Step 3: The Filtering Mechanism (Killing the Noise)

A major complaint about AI tools is the False Alarm Rate (FAR). If an AI warns you about 10 things and 9 are wrong, you will ignore the 10th one—even if it’s a critical security flaw.

To combat this, the Reviewer and Validator agents assign three scores to every potential comment (on a scale of 1-7):

- Q1: Nitpick Score: Is this just a style suggestion? (High score = yes).

- Q2: Fake Problem Score: Is this a hallucination? (High score = yes).

- Q3: Severity Score: Is this a critical bug? (High score = yes).

The system applies a Coarse Filter (discarding comments with high Nitpick/Fake scores) and then a Fine Filter via the Meta-Reviewer and Validator. This ensures that the only comments that reach the developer are ones the system is confident are serious.

Step 4: Line Number Localization

It sounds simple, but telling the developer where the comment belongs is hard. Code changes shifting line numbers can confuse LLMs.

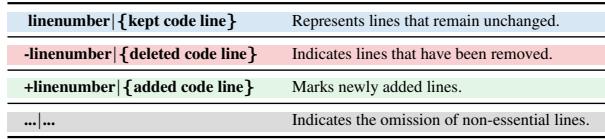

The authors use a specific “Inline” formatting strategy. Instead of just giving the code, they explicitly number the lines and mark changes with +, -, or space (kept).

As shown in Table 1, this format helps the LLM “see” the exact location of the code, significantly increasing the Line Localization Success Rate (LSR).

Experimental Setup & Metrics

The researchers didn’t use standard open-source datasets (which are often just snippets). They mined their company’s Fault Reports. These are historical records of actual bugs that caused production incidents (money loss, crashes). They traced these bugs back to the original Merge Request to see if the AI could catch them.

The Metrics

Because BLEU is useless here, they defined new metrics:

1. Key Bug Inclusion (KBI):

\[ { \mathrm { K B I } } = { \frac { \mathrm { N u m b e r ~ o f ~ r e c a l l e d ~ k e y ~ i s s u e s } } { \mathrm { T o t a l ~ n u m b e r ~ o f ~ k e y ~ i s s u e s } } } \times 1 0 0 \]Simply put: Did the AI find the bug that caused the crash?

2. False Alarm Rate (FAR):

\[ F A R _ { 1 } = \frac { 1 } { N } \sum _ { i = 1 } ^ { N } \left( \frac { \mathrm { N u m b e r ~ o f ~ f a l s e ~ a l a r m ~ c o m m e n t s ~ i n ~ M R } _ { i } } { \mathrm { T o t a l ~ n u m b e r ~ o f ~ c o m m e n t s ~ i n ~ M R } _ { i } } \times 1 0 0 \right) \]Simply put: What percentage of the AI’s comments were useless garbage?

3. Comprehensive Performance Index (CPI):

\[ \mathrm { C P I } _ { 1 } = 2 \times \frac { \mathrm { K B I } \times ( 1 0 0 \mathrm { - F A R _ { 1 } } ) } { \mathrm { K B I } + ( 1 0 0 \mathrm { - F A R _ { 1 } } ) } \]This is like an F1-score. It balances finding bugs (KBI) with staying quiet (FAR).

Results: Does it Work?

The short answer is yes. The system significantly outperformed existing baselines (like CodeReviewer and LLaMA-Reviewer).

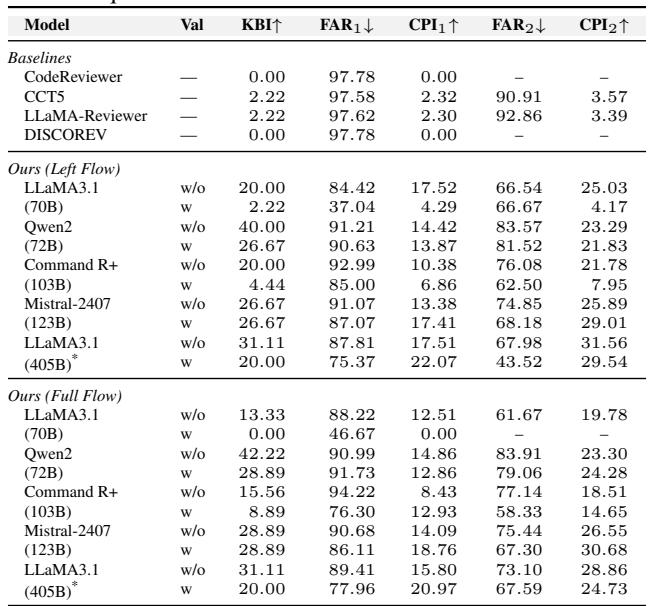

Table 2 below shows the comparison. Look at the CPI1 column (Comprehensive Performance). The Baselines score between 0.00 and 2.32. The proposed framework (Ours) reaches as high as 22.07 when using LLaMA3.1 (70B/405B).

Result Highlight 1: Slicing Matters

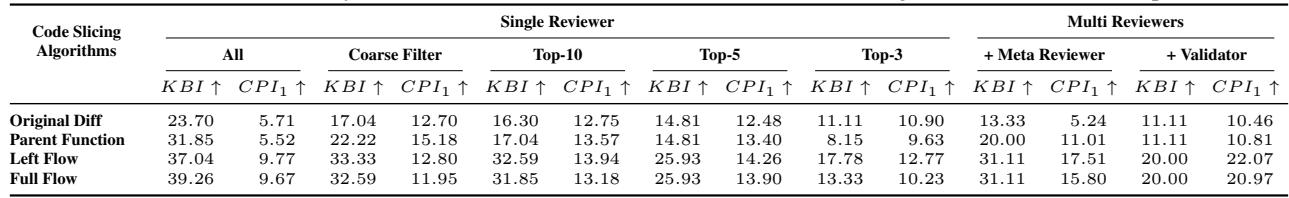

The team compared their four slicing algorithms. Table 3 reveals a clear winner.

The Left Flow and Full Flow algorithms (the ones that trace variable definitions) achieved significantly higher KBI and CPI than the simple “Original Diff” or “Parent Function” methods. This proves that context is king. You cannot review code effectively if you don’t know where the data is coming from.

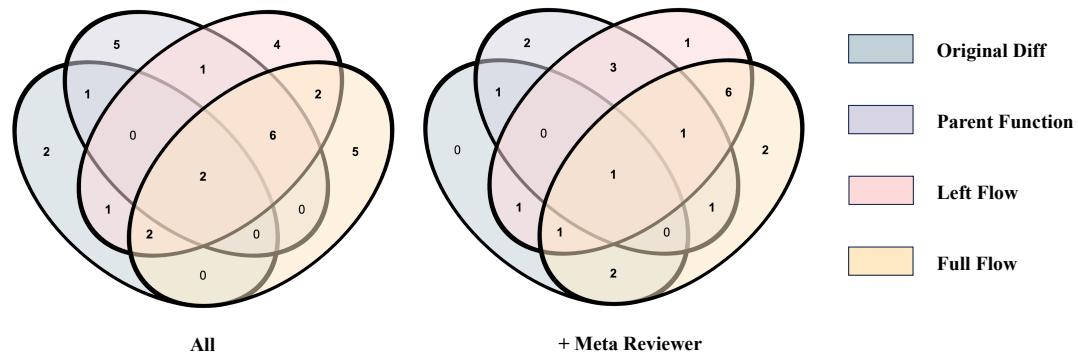

Interestingly, looking at the overlap of bugs found (Figure 4), different slicing methods catch different bugs.

While flow-based methods (Left/Full) catch the most, there are unique bugs that only the Parent Function or Original Diff caught. This suggests that a hybrid approach might be the ultimate solution.

Result Highlight 2: The Trade-off of Roles

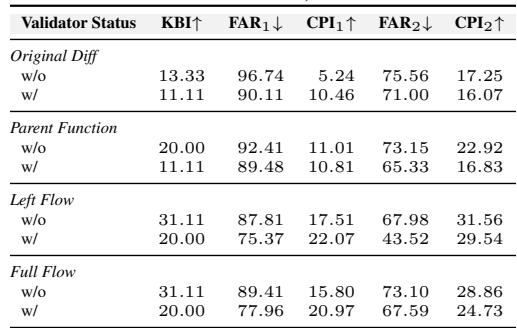

Adding more reviewers helps find more bugs, but it adds noise. This is where the Validator role shines.

In Table 5, compare the rows with and without the Validator (w/ vs w/o).

- Without Validator: High KBI (finds many bugs), but High FAR (lots of noise).

- With Validator: FAR drops significantly. KBI drops slightly (some real bugs get filtered out), but the overall utility (CPI) usually remains high or improves in stability. The Validator acts as a necessary filter to keep developers from turning the tool off in frustration.

Conclusion: The Future of Automated Review

This paper represents a shift in how we think about AI in software engineering. We are moving away from treating code as “natural language” to be translated, and towards treating it as a structured logical system that requires context and reasoning.

The key takeaways for students and practitioners are:

- Context is Non-Negotiable: Simple diffs aren’t enough. Static analysis (Code Slicing) is required to feed LLMs the info they need.

- Specialization Wins: Breaking the task into roles (Reviewer, Validator) works better than one giant prompt.

- Optimize for Precision: In the real world, a low False Alarm Rate is more important than a high recall. If an AI annoys a developer, it gets ignored.

By combining traditional static analysis (slicing) with the reasoning power of modern LLMs, this framework paves the way for AI that doesn’t just nitpick your variable names, but actually stops the next production outage.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2505.17928/images/cover.png)