Introduction

In traditional democratic processes, the menu of options is usually fixed. You vote for Candidate A or Candidate B; you choose between Policy X or Policy Y. But what happens when the goal isn’t just to choose from a pre-defined list, but to synthesize the complex, unstructured opinions of thousands of people into a coherent set of representative statements?

This is the challenge of Generative Social Choice.

Imagine a town hall meeting with 10,000 residents. It is impossible to let everyone speak, and it is equally difficult to have a human moderator manually summarize every distinct viewpoint without bias. Recently, researchers have turned to Large Language Models (LLMs) to solve this. Systems like Polis have already been used in Taiwan and by the United Nations to cluster opinions. However, moving from “clustering” to a mathematically rigorous selection of representative statements is a hard problem.

Existing frameworks for Generative Social Choice have shown promise, but they rely on two dangerous assumptions:

- Uniformity: They assume all statements are created equal (same length, same complexity).

- Perfection: They assume the AI understands human preferences perfectly.

In the real world, attention is a scarce resource (a “budget”), and LLMs hallucinate or misjudge preferences (they are “approximate”).

In this post, we dive deep into the paper “Generative Social Choice: The Next Generation” by Boehmer, Fish, and Procaccia. We will explore how they upgraded the theoretical framework of AI-assisted democracy to handle cost constraints and AI errors, culminating in a new engine called PROSE that can digest raw user comments and output a provably representative slate of opinions.

Background: From Elections to Generation

To understand the contribution of this paper, we must first ground ourselves in Computational Social Choice.

Committee Elections and Participatory Budgeting

Classically, if we want to select a committee of \(k\) representatives, we look for a subset of candidates that best represents the voters. If we add “costs” to the mix—where different candidates cost different amounts of money—we enter the realm of Participatory Budgeting (PB). In PB, a city might let voters decide how to spend \(1 million. A park costs \)500k; a bike lane costs $100k. The goal is to select a bundle of projects that respects the budget and maximizes voter satisfaction.

The Generative Twist

In Generative Social Choice, the “candidates” are not people or pre-defined projects. The candidates are all possible statements that could be written in a language.

Because this “universe of statements” is infinite, we cannot simply list them on a ballot. We need a mechanism to:

- Generate candidate statements that might appeal to groups of voters.

- Evaluate (discriminate) how much a specific voter would like a specific statement.

Fish et al. (2024) proposed a two-step framework using LLMs to perform these query tasks. However, their model was rigid. It required a fixed number of statements (e.g., “produce exactly 5 statements”), ignoring the fact that one long, nuanced statement might be worth two short, punchy ones. Furthermore, their math broke down if the LLM wasn’t 100% accurate in predicting user happiness.

This new work bridges the gap between abstract theory and the messy reality of AI deployment.

Core Method: Budgets and Approximate Queries

The authors propose a new democratic process that accounts for budgets (e.g., a total word count limit for the final report) and errors (the LLM might be wrong).

1. The Model

We assume there is a set of agents \(N\) (the voters) and a budget \(B\). The “universe” of statements \(\mathcal{U}\) is unknown. Every statement \(\alpha\) has a cost \(c(\alpha)\) (its length).

Every agent \(i\) has a utility function \(u_i(\alpha)\) determining how much they agree with a statement. However, because we cannot ask every user about every possible sentence in the English language, we rely on Queries.

2. The Queries (and their Errors)

The heart of this paper is the formalization of how we interact with the LLM. The authors define two specific types of queries. Crucially, they model the errors these queries might produce.

The Discriminative Query

This query predicts a user’s utility.

- Ideal: \(DISC(i, \alpha) = u_i(\alpha)\)

- Approximate: The LLM is \(\beta\)-accurate. It returns a value within \(\pm \beta\) of the truth.

The Generative Query

This is the heavy lifter. We give the LLM a set of agents \(S\), a target utility level \(\ell\), and a cost limit \(x\). We ask: “Write a statement costing at most \(x\) that the maximum number of people in group \(S\) would approve at level \(\ell\).”

Because LLMs are probabilistic, they might fail in three ways:

- Supporter Count (\(\gamma\)): It might find a statement supported by fewer people than the optimal one (multiplicative error).

- Cost (\(\mu\)): It might overestimate the budget, effectively searching a smaller space (multiplicative error).

- Utility (\(\delta\)): The generated statement might be slightly less liked than requested (additive error).

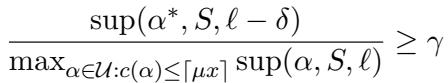

Mathematically, the authors define an approximate generative query using these parameters.

As shown in the equation above, the query guarantees that the statement returned is “good enough” relative to the true optimal statement, discounted by our error parameters \(\gamma\), \(\delta\), and \(\mu\). If \(\gamma=1, \mu=1, \delta=0\), we have a perfect query.

3. The Axiom: Cost-Balanced Justified Representation (cBJR)

How do we know if the final slate of statements is “fair”? The authors adapt a concept from social choice theory called Balanced Justified Representation (BJR).

Intuitively, cBJR states:

If a group of voters is large enough to “afford” a statement using their share of the budget, and there exists a statement they all agree on, then they must be represented in the final slate by something they like (at least somewhat).

If a group makes up 20% of the population, they essentially control 20% of the word count budget. If they are cohesive (they all agree on a topic), the algorithm cannot ignore them.

4. The Algorithm: DemocraticProcess

The researchers introduce an algorithm named DemocraticProcess. It is a greedy, iterative approach designed to satisfy cBJR even when the queries are imperfect.

How it works:

- Initialization: Start with the full set of agents \(S\) and an empty slate.

- Iterate Utility: Start asking for statements with the highest possible approval (e.g., “Strongly Agree”). Gradually lower the bar to “Agree,” then “Neutral.”

- Iterate Costs: For each approval level, check different statement lengths (costs).

- Greedy Selection:

- Call the Generative Query to find a statement \(\alpha^*\) that a subset of the remaining agents \(S\) likes.

- Check if the group \(S_{\alpha^*}\) (the supporters) is large enough to “pay” for this statement using their share of the budget (\(|S_{\alpha^*}| \ge \lceil c(\alpha^*) \cdot n / B \rceil\)).

- If yes, add the statement to the slate.

- Remove the supporters from the set \(S\) (they are now represented).

- Repeat until the budget is full or everyone is represented.

Theoretical Guarantees

The authors prove that this algorithm provides a specific guarantee: \((\dots)\)-cBJR. The specific numbers inside the guarantee depend on the errors of the LLM.

If the LLM makes errors (\(\beta, \gamma, \delta, \mu\)), the fairness of the result degrades gracefully. The paper proves that no algorithm can perfectly overcome these errors, but DemocraticProcess comes very close to the theoretical limit.

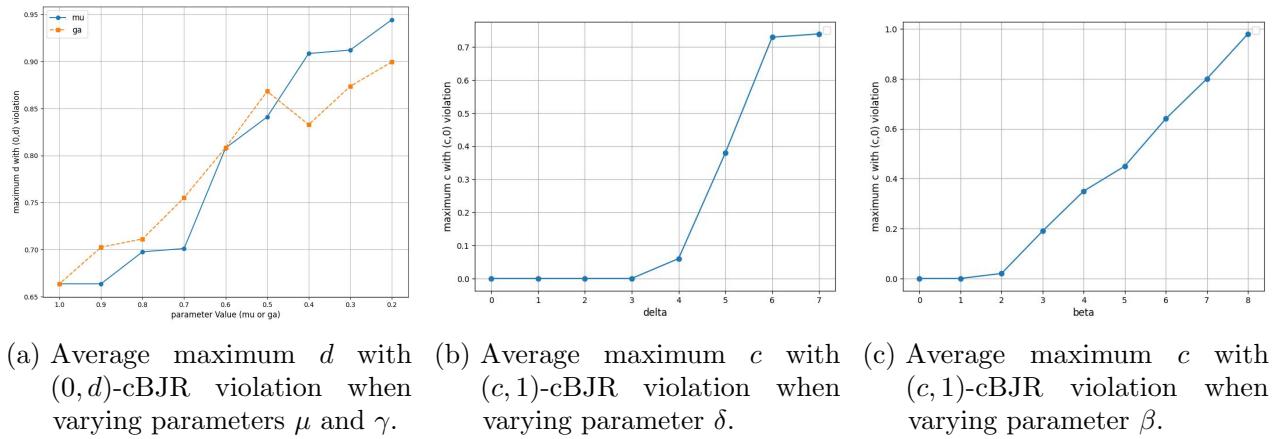

The figure above illustrates this degradation. As the error parameters (like \(\beta\) for discriminative accuracy or \(\mu\) for cost accuracy) increase, the “violation” of proportionality increases. However, the complex version of their algorithm (which searches the full cost space) remains robust much longer than naive baselines.

Implementation: Introducing PROSE

Theory is useful, but does it work on actual text? The authors built PROSE (Proportional Slate Engine), a practical implementation of their algorithm using GPT-4o.

Handling Unstructured Data

Unlike previous systems that required users to vote on specific surveys, PROSE takes unstructured text (e.g., comments on a forum, reviews) and a total word budget.

Implementing the Queries

- Discriminative: They prompt GPT-4o to act as a proxy for the user. They feed the user’s past comments and the new statement to the model, asking it to rate agreement on a scale of 1-6. They even calibrate for “specificity” to prevent the model from preferring vague horoscopes (statements that apply to everyone but say nothing).

- Generative: This is harder. They use a two-step process:

- Clustering/Embedding: Use vector embeddings to find “cohesive” groups of users who are close to each other in opinion space.

- Drafting: Feed the comments of that specific cluster to GPT-4o and ask it to write a consensus statement within a specific word limit.

Experiments and Results

The authors tested PROSE on two very different domains:

- Drug Reviews: Users reviewing birth control and obesity medication (high variance in opinion, distinct subgroups).

- Civic Participation: A “Polis” dataset from Bowling Green, KY, regarding city improvement planning.

They compared PROSE against several baselines:

- Clustering: Standard K-means clustering of opinions.

- Zero-Shot: Just asking GPT-4o, “Write a summary of these opinions.”

- PROSE-UnitCost: A version of their engine that ignores statement length (treating every statement as cost = 1).

Quantitative Success

To evaluate the results, they used a “Chain-of-Thought” (CoT) evaluator—a more expensive, slower, and rigorous LLM prompt—to judge the final slates. This ensured they weren’t grading their homework with the same prompt used to generate it.

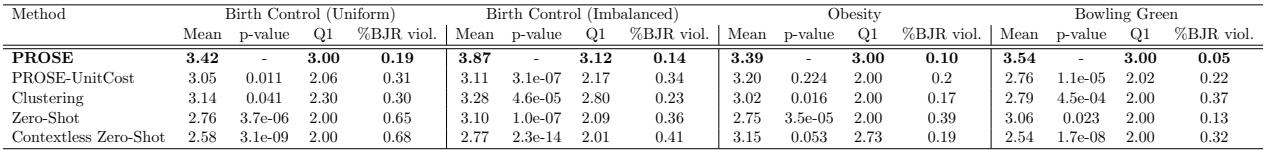

The results were significant.

As seen in the table above, PROSE (top row) consistently achieved the highest Average Utility for users. Perhaps more importantly, look at the Q1 (25th Percentile) or “10th-percentile” metrics (often a proxy for minority representation). PROSE significantly outperforms the “Zero-Shot” and “Clustering” baselines.

This confirms the theoretical hypothesis: simply asking an LLM to “summarize” (Zero-Shot) tends to wash out minority opinions in favor of the majority. By using the greedy, iterative DemocraticProcess, PROSE ensures that once the majority is “satisfied” and removed from the pool, the algorithm hunts for the next largest cohesive group to satisfy, ensuring proportionality.

Simulation Analysis

The authors also ran simulations in a synthetic environment where they could control the exact error rates of the “LLM.”

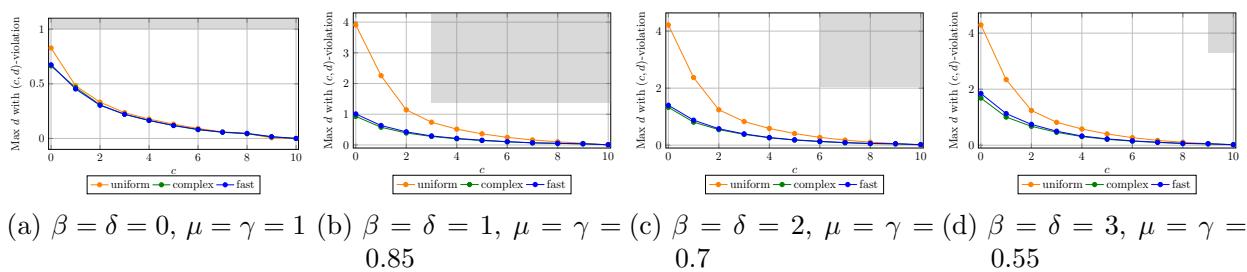

In Figure 1 above, we see the simulation results. The Uniform baseline (orange line) fails to achieve proportionality (high violation on the y-axis) almost immediately. The Complex algorithm (green line)—which is the full implementation of PROSE—maintains low violations even as the problem complexity (\(c\), the cost) increases. The shaded gray region represents the theoretical guarantee derived in the paper; remarkably, the actual performance is often better than the worst-case mathematical guarantee.

Qualitative Success

The generated slates were not just mathematically superior; they made sense.

- In the Bowling Green dataset, PROSE identified distinct groups advocating for specific issues: traffic improvements, internet infrastructure, and school boundaries.

- In the Drug Review dataset, it captured the nuance of users who found the drug effective but suffered specific side effects, rather than just averaging them into a “it’s okay” sentiment.

Conclusion & Implications

“Generative Social Choice: The Next Generation” moves the field from a neat idea to a workable engineering problem. By acknowledging that LLMs are imperfect and that real-world reports have length limits, the authors have created a framework that is robust enough for real deployment.

Key Takeaways

- Budgets Matter: You cannot simply ask for “a summary.” You must define the attention budget (word count), and the algorithm must allocate that budget proportionally to the prevalence of opinions.

- Greedy is Good: The iterative removal of satisfied users ensures that minorities get their turn in the slate, satisfying the cBJR axiom.

- Robustness to Error: The system works even when the AI makes mistakes, provided those mistakes are within reasonable bounds.

The Future of Digital Democracy

The immediate application of PROSE is in summarizing large-scale consultations—thousands of comments on a city planning website or product reviews. But the long-term vision is Participatory Budgeting.

Imagine a city where thousands of residents submit ideas for urban renewal. Instead of a human committee filtering them down, an engine like PROSE could generate a slate of projects that mathematically guarantees fair representation for every cohesive group of citizens. While we must remain cautious about AI bias and transparency (as the authors note in their Impact Statement), this work provides the mathematical guardrails necessary to use these powerful tools safely in the democratic process.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2505.22939/images/cover.png)