Breaking the Codebook Collapse: How STAR Teaches Robots Diverse Skills via Geometric Rotation

Imagine trying to teach a robot to cook a meal. You don’t tell the robot every single millisecond of muscle movement required to crack an egg. Instead, you think in terms of “skills”: grasp the egg, hit the edge of the pan, pull the shells apart.

This hierarchical approach—breaking complex long-horizon tasks into discrete, reusable skills—is the holy grail of robotic manipulation. However, translating continuous robot actions into these discrete “words” or “tokens” is notoriously difficult. Current methods often suffer from codebook collapse, where the robot ignores most of the skills it could learn, relying on just a tiny subset of repetitive actions. Furthermore, even if the robot learns the skills, stringing them together smoothly (composition) is a separate headache.

In this post, we are diving deep into STAR (Skill Training with Augmented Rotation), a new framework presented at ICML 2025. STAR introduces a clever geometric trick to fix the codebook collapse problem and utilizes a causal transformer to chain these skills together for complex tasks like opening drawers or organizing objects.

The Problem: Why Robot Skills “Collapse”

To understand STAR, we first need to understand how modern robots learn “skills.” A popular method is Vector Quantization (VQ).

The Intuition Behind VQ

Think of VQ as a translator. The robot sees a continuous stream of messy action data (joint angles, velocities). VQ attempts to map these continuous movements to the nearest “prototype” movement in a fixed dictionary, known as a codebook.

If the codebook has 100 entries, ideally, the robot should learn 100 distinct skills (e.g., push left, lift up, twist knob).

The Reality: Codebook Collapse

In practice, neural networks are lazy. When training a VQ-VAE (Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder), the model often finds that using just 3 or 4 of those 100 codes is “good enough” to minimize error early in training. It stops exploring the rest of the dictionary.

This is called codebook collapse. The result? A robot that lacks diversity. It might know how to “push forward” generally, but it lacks the nuance to “push gently” versus “shove hard” because all those variations collapsed into a single, crude skill code.

The culprit is often the way gradients are calculated. Because the “snapping” operation (rounding to the nearest code) is not differentiable, researchers use a hack called the Straight-Through Estimator (STE). STE essentially pretends the gradient is passed through unchanged. But this ignores the geometry of the embedding space, leading to poor updates and the eventual death of codebook diversity.

Enter STAR: A Two-Stage Solution

The STAR framework addresses these issues in two distinct stages:

- RaRSQ (Rotation-augmented Residual Skill Quantization): A better way to learn the dictionary of skills without collapsing.

- CST (Causal Skill Transformer): A better way to string those skills together to perform tasks.

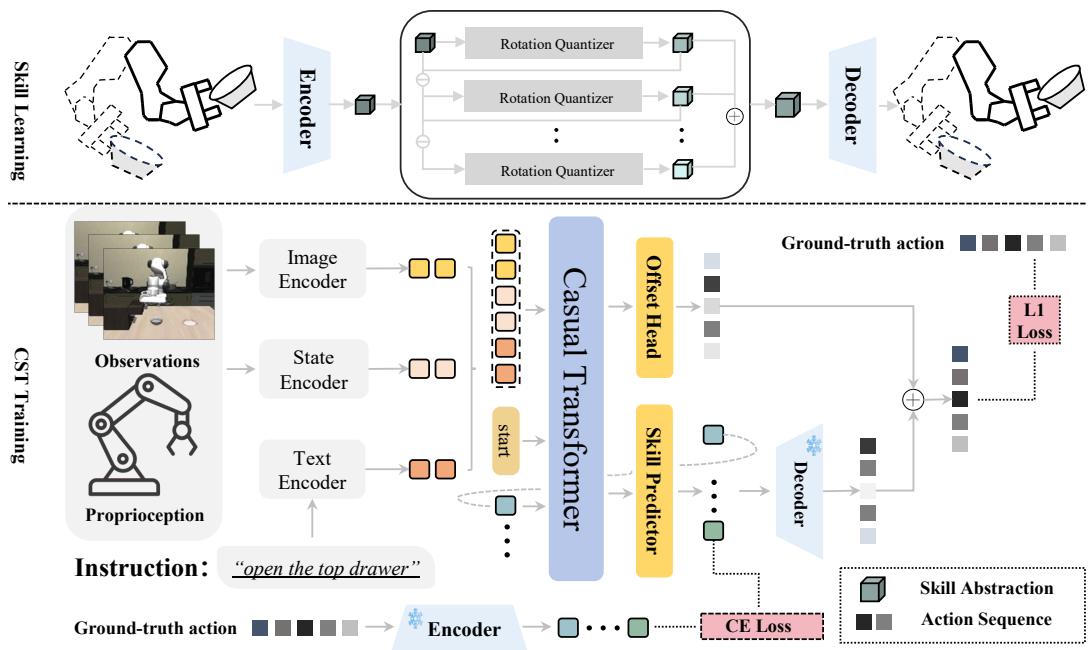

Let’s look at the high-level architecture:

As shown in Figure 2, the top half focuses on learning the skills (RaRSQ), while the bottom half focuses on using them (CST).

Part 1: RaRSQ (Learning Diverse Skills)

The core innovation of STAR is how it handles the quantization process. The authors propose Rotation-augmented Residual Skill Quantization (RaRSQ).

The “Residual” Aspect

Instead of mapping an action to just one code, RaRSQ uses a hierarchy. It’s like describing a location:

- Level 1 (Coarse): “New York City”

- Level 2 (Fine): “Times Square”

Mathematically, the system calculates a residual. It finds the closest code for the action, subtracts that code from the action, and then tries to quantize the remainder (the residual) using a second codebook.

The “Rotation” Trick

This is the mathematical heart of the paper. Standard VQ methods simply copy the gradient from the decoder to the encoder (STE). This ignores the angular relationship between the encoder’s output and the codebook vector.

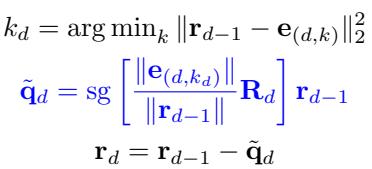

STAR replaces this with a rotation-based gradient flow. Instead of just snapping the vector to the code, it calculates a rotation matrix \(\mathbf{R}\) that aligns the input residual \(\mathbf{r}\) with the codebook vector \(\mathbf{e}\).

The update rule looks like this:

Here, sg stands for stop-gradient. The system rotates the residual to match the codebook vector’s direction.

Why does this matter?

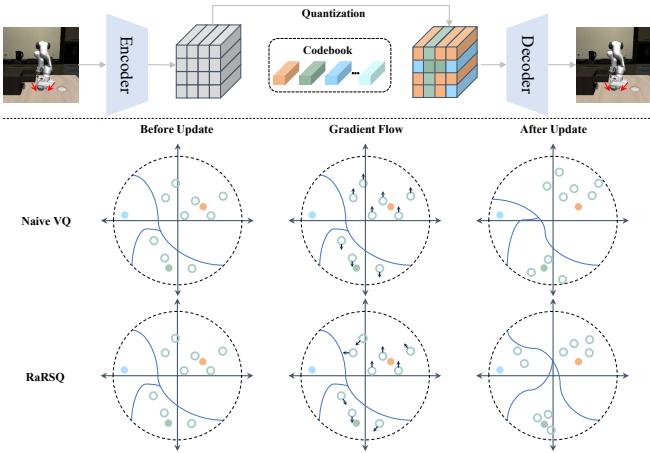

Look at Figure 1 below. It compares Naive VQ (using STE) with RaRSQ.

In the Naive VQ (middle row), the gradients (arrows) are identical for all points assigned to a specific code. They all get pushed in the exact same direction. This causes the embeddings to clump together aggressively, leaving other codes unused.

In RaRSQ (bottom row), the gradients are derived from rotation. This preserves the relative angles. Points are pushed or pulled based on their geometric relationship to the code. This “fanning out” of gradients prevents the embeddings from collapsing into a single point, maintaining a rich, diverse space where many skills can coexist.

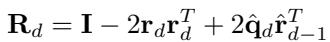

The Rotation Matrix

For those interested in the math, the rotation matrix \(\mathbf{R}_d\) is constructed to align the residual \(\mathbf{r}_{d-1}\) with the chosen code vector. The formula ensures that the geometric structure is encoded into the gradient flow:

This mechanism ensures that when the network updates its weights during backpropagation, it respects the geometry of the latent space, forcing the model to distinguish between slightly different actions rather than lumping them together.

Part 2: CST (Composing Skills)

Once RaRSQ has learned a diverse library of skills (represented as discrete codes), we need a brain to select them. This is the Causal Skill Transformer (CST).

Autoregressive Prediction

Robotic tasks are sequential. You must grasp before you lift. CST models this dependency explicitly. It uses a transformer to predict the next skill code based on the history of observations (images, robot state) and previous skills.

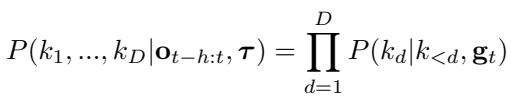

The probability of a sequence of skills is modeled as:

Because RaRSQ uses a residual hierarchy (Coarse \(\to\) Fine), CST predicts the Level 1 code first, and then conditions on that to predict the Level 2 code. This mirrors how humans plan: decide on the general motion first, then refine the details.

Action Refinement (The Offset)

Discrete codes are great for reasoning, but the real world is continuous. A discrete code might say “move hand to coordinate (10, 10),” but the object is actually at (10.1, 9.9). If the robot relies solely on the discrete code, it will be clumsy.

To solve this, CST includes a continuous offset head. It predicts a small, continuous adjustment \(\zeta_{\text{ref}}\) to add to the decoded action.

This hybrid approach gives the robot the best of both worlds: the structured reasoning of discrete skills and the high-precision control of continuous regression.

Training Objective

The CST is trained with a dual objective: it must accurately classify the correct skill code (using Cross-Entropy loss) and accurately predict the continuous action trajectory (using Mean Squared Error).

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested STAR on two major benchmarks: LIBERO (a suite of 130 language-conditioned tasks) and MetaWorld MT50.

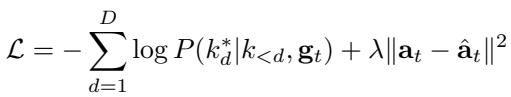

Does it beat the state-of-the-art?

Yes, and by a significant margin.

In the MetaWorld MT50 benchmark, which consists of 50 distinct manipulation tasks, STAR achieved a 92.7% success rate, consistently outperforming strong baselines like Diffusion Policy and VQ-BeT.

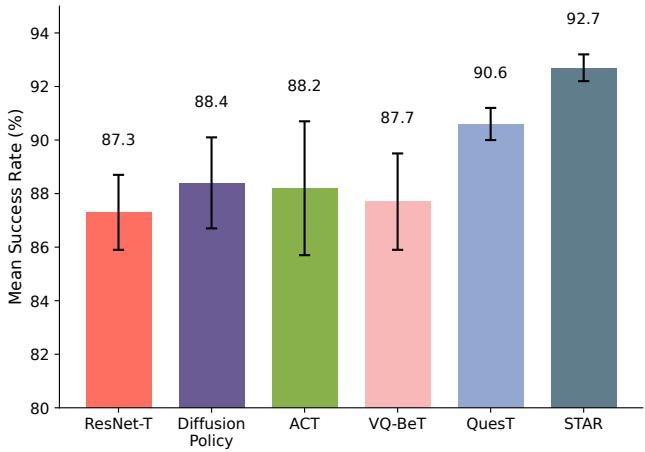

The results on LIBERO were even more telling. LIBERO includes “Long-Horizon” tasks, which are notoriously difficult because errors accumulate over time.

Looking at Table 1 (above), notice the LIBERO-Long column.

- ACT: 44.0%

- VQ-BeT: 59.7%

- QueST: 69.1%

- STAR (Ours): 88.5%

That is a massive ~19% jump in performance over the previous state-of-the-art (QueST). This suggests that STAR’s ability to maintain diverse skills and refine them allows it to handle long sequences without losing track or precision.

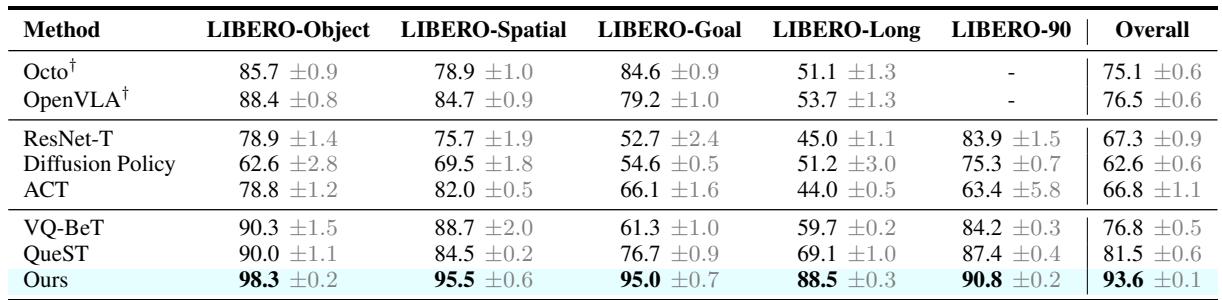

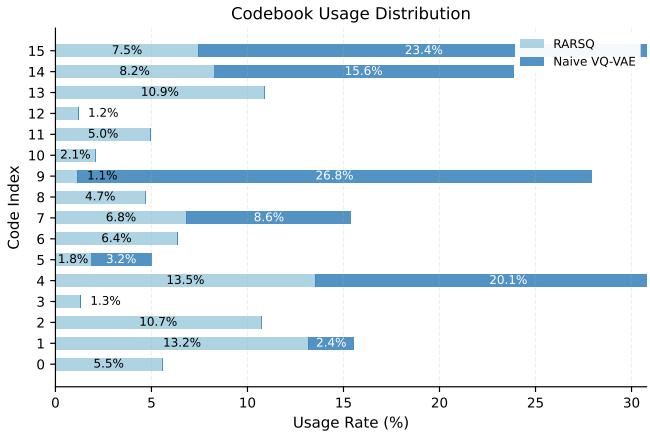

Did it fix Codebook Collapse?

The authors claim RaRSQ prevents collapse. They proved this by analyzing how often each code in the codebook was used during training.

Figure 4 is the “smoking gun.”

- Naive VQ-VAE (Dark Blue): It heavily overuses Code 0 and Code 4, while ignoring almost half the dictionary (codes 8-13 are barely touched). This is classic collapse.

- RaRSQ (Light Blue): The usage is distributed across all 16 codes. The robot effectively learned 16 distinct skill primitives instead of just 7, giving it a much richer vocabulary of movements to draw from.

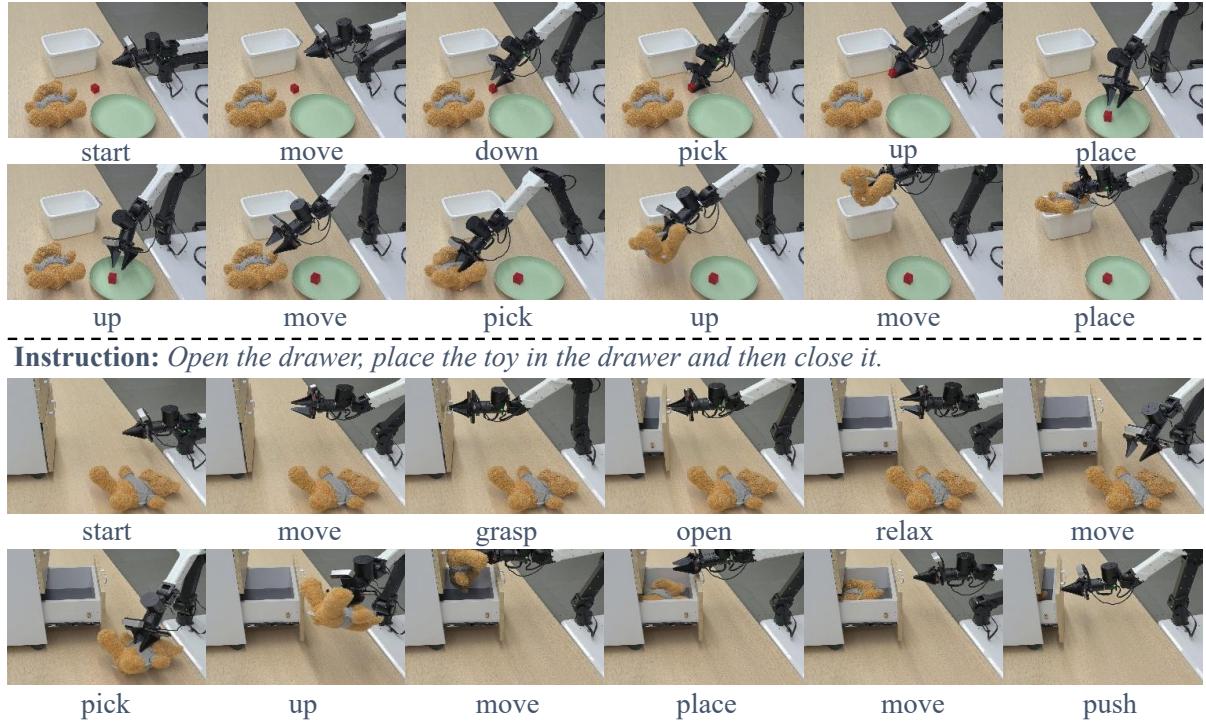

Real-World Performance

Simulation is fine, but can it work on a real robot? The authors tested STAR on an ALOHA robot arm performing sequential tasks, such as “Pick the cube into the plate and pick the toy into the box.”

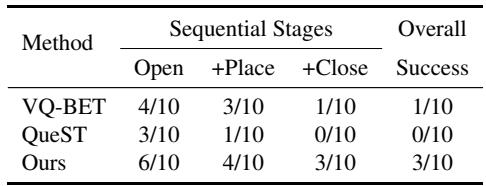

In these tests, STAR showed superior stability. For example, in a drawer opening/closing task, baseline methods often failed after the first step (opening), unable to transition to placing the object. STAR maintained coherence throughout the sequence.

As shown in Table 3, while other methods (VQ-BeT, QueST) struggled to complete the full sequence (0/10 and 1/10 success), STAR successfully completed the full “Open \(\to\) Place \(\to\) Close” chain 30% of the time, with high success rates on the individual stages.

Why This Matters

The STAR framework provides a significant step forward in Hierarchical Imitation Learning.

- Geometry Matters: It highlights that we cannot simply treat vector quantization as a “black box.” By respecting the geometry of the latent space (via rotation), we get better gradients and richer representations.

- Diversity is Key: A robot with a small vocabulary of skills is a clumsy robot. Preventing codebook collapse is essential for handling the variability of the real world.

- Composition + Refinement: Merely picking a skill isn’t enough; you need to refine it. The combination of the Causal Transformer with the continuous offset head ensures that high-level planning meets low-level motor control.

By solving the “collapse” of discrete representations, STAR allows robots to learn a true library of diverse skills, bringing us closer to general-purpose robotic helpers that can cook, clean, and organize without needing a hard-coded script for every movement.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2506.03863/images/cover.png)