Introduction

In the world of safety-critical AI—think autonomous driving, medical diagnosis, or flight control systems—“pretty good” isn’t good enough. We need guarantees. We need to know for a fact that if a stop sign is slightly rotated or has a sticker on it, the car’s neural network won’t misclassify it as a speed limit sign.

This is the domain of Neural Network Verification. The goal is to mathematically prove that for a given set of inputs (a “perturbation set”), the network will always produce the correct output.

Historically, researchers have been stuck between a rock and a hard place:

- Linear Bound Propagation (LBP): Methods like CROWN or \(\alpha\)-CROWN are incredibly fast and scale to massive networks. However, they can be “loose,” meaning they might fail to verify a safe network because their mathematical approximations are too conservative.

- Semidefinite Programming (SDP): These methods offer much tighter, more precise bounds. The catch? They are excruciatingly slow. Their computational complexity scales cubically (\(O(n^3)\)), making them impossible to use on modern, large-scale deep learning models.

Enter SDP-CROWN.

In a new paper from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, researchers have proposed a hybrid framework that bridges this gap. By cleverly using the principles of Semidefinite Programming to derive a new type of linear bound, they achieve the tightness of SDP with the speed of bound propagation.

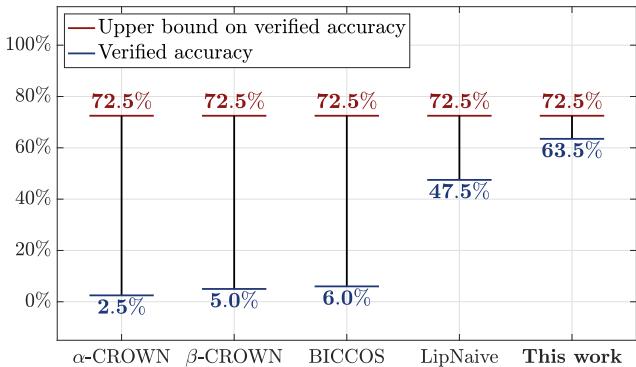

As shown in Figure 1, the difference is not marginal. On large convolutional networks where traditional fast verifiers achieve only 2.5% to 6.0% verified accuracy against \(\ell_2\) attacks, SDP-CROWN achieves a striking 63.5%, approaching the theoretical upper bound.

In this post, we will tear down the mathematics of this paper, explain why traditional methods struggle with specific types of attacks, and how SDP-CROWN solves the problem by adding just a single parameter per layer.

The Background: What Are We Verifying?

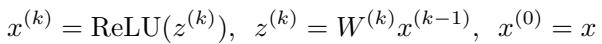

Before diving into the solution, let’s define the problem. We treat a neural network \(f(x)\) as a sequence of linear transformations (weights \(W\)) and non-linear activations (ReLU).

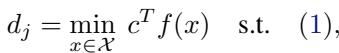

We want to ensure that for an input \(\hat{x}\) (e.g., an image of a panda), any adversarial example \(x\) within a certain distance remains classified correctly. If the correct class is \(i\), the score for class \(i\) must be greater than the score for any incorrect class \(j\). Mathematically, we want to find the minimum “margin” of safety:

If \(d_j\) is positive, we are safe. If it’s negative, an attack exists.

The Geometry of Attacks: Boxes vs. Balls

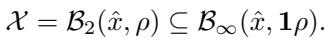

The shape of the “danger zone” around the input matters immensely.

- \(\ell_\infty\)-norm (The Box): This assumes each pixel can change independently by a small amount \(\epsilon\). Geometrically, this is a hyper-rectangle (or box).

- \(\ell_2\)-norm (The Ball): This assumes the total Euclidean distance of the change is bounded by \(\rho\). Geometrically, this is a hypersphere (or ball).

While bound propagation methods (like \(\alpha\)-CROWN) are excellent at handling “Box” perturbations, they are notoriously bad at handling “Ball” (\(\ell_2\)) perturbations.

The Problem: Why is Bound Propagation Loose for \(\ell_2\)?

Linear Bound Propagation (LBP) works by pushing linear constraints through the network layer by layer. It is designed to handle features individually. When you ask an LBP verifier to handle an \(\ell_2\) ball, it doesn’t know how to handle the curvature of the sphere.

To make the math work, standard LBP methods essentially wrap the sphere inside the tightest possible box (an \(\ell_\infty\) box) and verify that box instead.

This seems like a harmless approximation, but in high-dimensional spaces, it is disastrous.

- A sphere of radius \(\rho\) is contained in a box of side length \(2\rho\).

- However, the corners of that box are actually distance \(\sqrt{n}\rho\) away from the center.

In a high-dimensional network (where \(n\) is large), the box has a volume vastly larger than the sphere. You are asking the verifier to guarantee safety for a space that is up to \(\sqrt{n}\) times larger than the actual attack space. This leads to overly conservative results—the verifier says “I can’t promise this is safe” even when it is.

The Solution: SDP-CROWN

The researchers propose a method that captures the curvature of the \(\ell_2\) constraint without incurring the massive computational cost of full SDP solvers.

The Core Concept

Standard bound propagation finds linear lower and upper bounds for the network output:

\[ c^T f(x) \geq g^T x + h \]Here, \(g\) is the slope and \(h\) is the offset (bias).

SDP-CROWN keeps the efficient structure of propagating these linear bounds but calculates the offset \(h\) in a smarter way. Instead of using a box to calculate \(h\), it solves a specialized optimization problem derived from Semidefinite Programming.

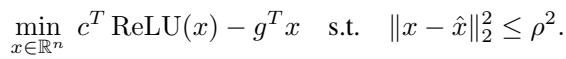

Step 1: The Primal Problem

To find the tightest possible offset \(h\) for a given slope \(g\) inside an \(\ell_2\) ball, we theoretically want to solve this minimization:

This looks simple, but the \(\text{ReLU}(x)\) term makes it non-convex and hard to solve exactly.

Step 2: The SDP Relaxation

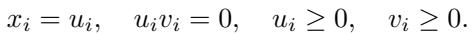

To solve this, the authors employ a classic trick from robust control theory: SDP Relaxation. They treat the ReLU constraint \(x = \text{ReLU}(z)\) not as a hard non-linearity, but as a quadratic constraint.

If \(x = \text{ReLU}(z)\), we can split variables into positive and negative parts (\(u\) and \(v\)) such that \(u \geq 0, v \geq 0\) and their product is zero (\(u \odot v = 0\)).

By relaxing the constraint \(u \odot v = 0\) (which is hard) into a positive semidefinite matrix constraint, they obtain a convex problem. This is where standard SDP methods stop—they throw this massive matrix into a solver, which takes \(O(n^3)\) time.

Step 3: The Efficient Dual

Here is the main contribution of the paper. The researchers didn’t stop at the matrix formulation. They derived the Lagrangian dual of this specific SDP relaxation.

By doing the math analytically, they realized that for this specific structure, the massive matrix optimization collapses into a problem that requires optimizing only one scalar variable per layer, denoted as \(\lambda\).

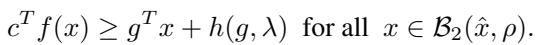

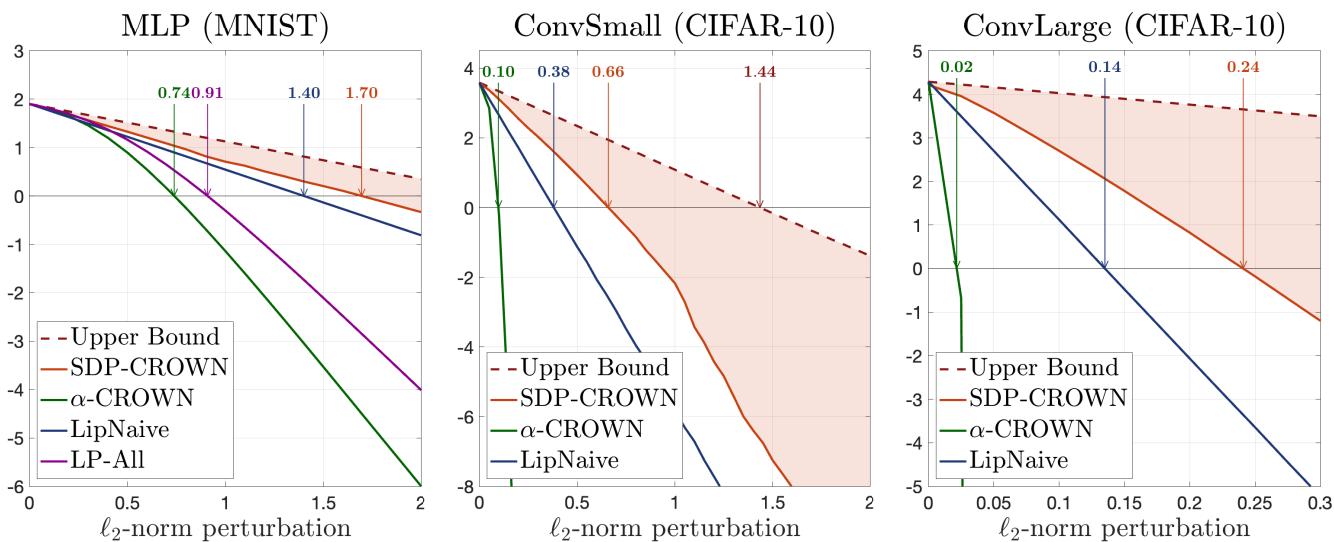

The resulting bound is stated in Theorem 4.1:

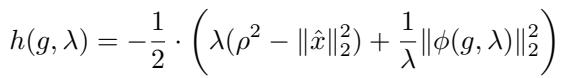

Where the offset \(h(g, \lambda)\) is defined as:

And \(\phi\) is a specific vector function:

Why is this huge?

- Complexity: We are no longer solving a matrix problem. We are maximizing a function of a scalar \(\lambda \geq 0\). This is cheap and fast.

- Compatibility: This calculation for \(h(g, \lambda)\) can be swapped directly into existing bound propagation tools like \(\alpha\)-CROWN. You simply replace the “Box-based” offset calculation with this “SDP-based” calculation.

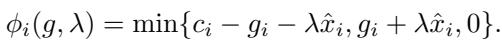

Visualizing the Improvement

To understand why this math matters, look at the geometry of the relaxation. The paper provides a visualization of the bounds produced by standard methods versus SDP-CROWN for a simple 2-neuron case.

- Left (Standard LBP): The relaxation is sharp and angular. It’s optimized for a box, so when applied to a ball, it leaves large gaps (looseness) between the bound and the true function.

- Right (SDP-CROWN): The relaxation is smooth and hugs the function surface tightly. This shape comes from implicitly handling the \(\ell_2\) constraint via the \(\lambda\) parameter.

The authors prove theoretically that when the perturbation is centered at zero, SDP-CROWN is exactly \(\sqrt{n}\) times tighter than standard bound propagation.

Experiments and Results

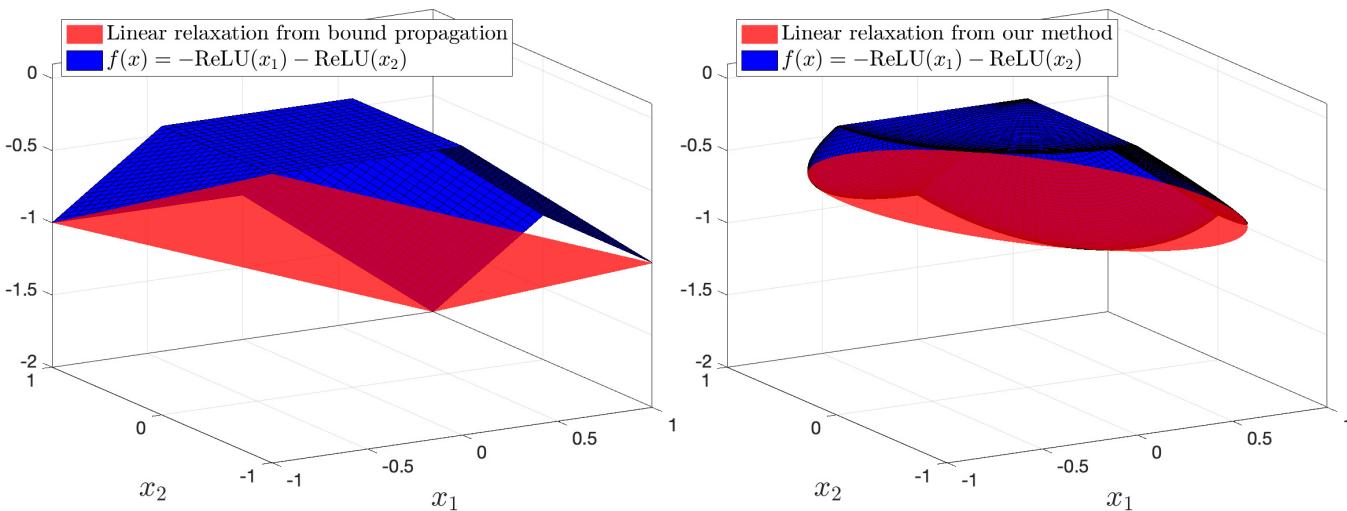

The theory sounds great, but does it work on real networks? The authors tested SDP-CROWN on MNIST and CIFAR-10 models, comparing it against:

- \(\alpha\)-CROWN / \(\beta\)-CROWN: State-of-the-art bound propagation.

- LipNaive / LipSDP: Methods based on Lipschitz constants.

- LP-All / BM-Full: Pure convex relaxation methods (very slow).

Verification Accuracy

Referencing Table 1 (partially visible in the image deck below), the results are consistent. On the ConvLarge model (CIFAR-10), which has ~2.47 million parameters and 65k neurons:

| Method | Verified Accuracy | Time |

|---|---|---|

| \(\alpha\)-CROWN | 2.5% | 47s |

| LipNaive | 47.5% | 1.2s |

| SDP-CROWN (Ours) | 63.5% | 73s |

Traditional bound propagation falls apart completely (2.5%). The naive Lipschitz method is fast but loose. SDP-CROWN achieves a high certification rate while taking only marginally longer than the fast methods (73s vs 47s).

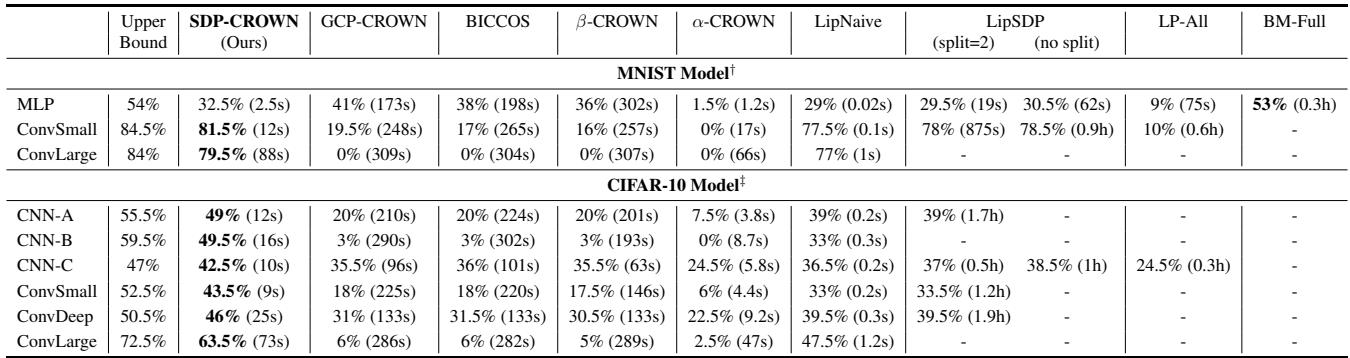

Tightness of Lower Bounds

It’s also instructive to look at the raw bounds. In verification, we want the lower bound of the correct class score to stay above 0.

In Figure 3, the x-axis represents the size of the attack (\(\ell_2\) radius). As the attack gets stronger, the certified lower bound drops.

- Blue Line (\(\alpha\)-CROWN): Drops below zero almost immediately for larger models.

- Red Line (SDP-CROWN): Hugs the upper bound (black line) much closer and stays positive for larger perturbation radii.

Conclusion

SDP-CROWN represents a significant step forward in the formal verification of neural networks. It successfully identifies the root cause of inefficiency in current methods—the mismatch between box-based verification tools and ball-based (\(\ell_2\)) adversarial attacks.

By going back to the mathematical drawing board and leveraging the dual of the Semidefinite Programming relaxation, the authors derived a formulation that is:

- Tight: capturing the true geometry of the attack.

- Efficient: adding only one parameter per layer rather than an \(n \times n\) matrix.

- Scalable: capable of verifying networks with millions of parameters.

For students and practitioners in robust AI, this paper highlights a valuable lesson: sometimes the best way to speed up an algorithm isn’t better code, but better math. By analytically solving the expensive part of the optimization before writing a single line of code, the researchers turned an intractable problem into a tractable one.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2506.06665/images/cover.png)