Introduction

“One example speaks louder than a thousand words.” This adage is particularly true in the world of Artificial Intelligence. When we want a model to solve a complex problem—like analyzing a geometry diagram or interpreting a historical chart—showing it a similar, solved example often works better than giving it a long list of instructions. This technique is known as In-Context Learning (ICL).

However, Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs)—the AI systems that can see and speak—still face significant hurdles. Despite their impressive capabilities, they are prone to hallucinations. They might confidently misstate a historical event or fail to answer a user’s question entirely because they lack specific domain knowledge.

To fix this, researchers typically use Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). The idea is simple: before the AI answers, it searches a database for relevant information (like a textbook or Wikipedia) and uses that to ground its answer. But here is the catch: standard RAG often retrieves facts without the logic behind them. It might find a similar image, but if the retrieved example doesn’t explain how to solve the problem, the AI is still left guessing.

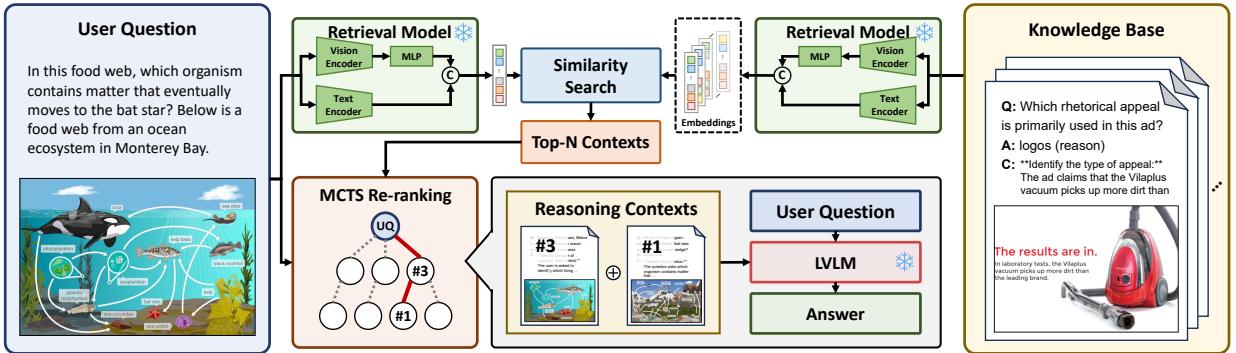

In this post, we will dive deep into a new framework called RCTS (Reasoning Context and Tree Search). This approach doesn’t just retrieve similar images; it constructs a “smart” knowledge base filled with step-by-step reasoning and uses a sophisticated search algorithm to decide exactly which examples will help the model the most.

The Problem with “Vanilla” RAG

Before we understand the solution, we need to understand the limitation of current methods.

Existing multimodal RAG methods function a bit like a student taking an open-book test. When asked a question, the student flips through the book, finds a page that looks relevant, and tries to answer. If the book contains just raw facts, the student might still fail to understand the underlying concept.

Current limitations include:

- Scarcity of Reasoning: Most datasets contain Question-Answer (QA) pairs. They tell you the answer is “C,” but they don’t tell you why. Without the “why,” the AI struggles to learn the pattern.

- Erratic Retrieval: Retrieval systems usually pick examples based on visual or semantic similarity. But just because two images look alike doesn’t mean they require the same logic to solve. If the AI retrieves a “distractor” example (one that looks similar but has a different solution method), it can actually confuse the model.

The RCTS framework aims to move LVLMs from merely “knowing” facts to “understanding” how to reason through them.

The RCTS Framework: An Overview

The researchers propose a three-stage pipeline designed to transform how LVLMs utilize external knowledge.

As shown in Figure 2, the process flows as follows:

- Knowledge Base Construction: Instead of a static database of questions and answers, the system builds a database enriched with Reasoning Contexts (step-by-step explanations).

- Hybrid Retrieval: When a user asks a question, the system retrieves potentially relevant examples using both visual and textual cues.

- MCTS Re-ranking: This is the core innovation. Instead of blindly trusting the top retrieved examples, the system uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to explore different combinations of examples and “re-rank” them to find the set that maximizes the probability of a correct answer.

Let’s break down these components in detail.

1. Constructing a Knowledge Base with “Reasoning Contexts”

If you want an AI to think logically, you must feed it logic. Standard datasets often look like this:

- Image: A picture of the Great Wall.

- Question: What is the purpose of this structure?

- Answer: Defense.

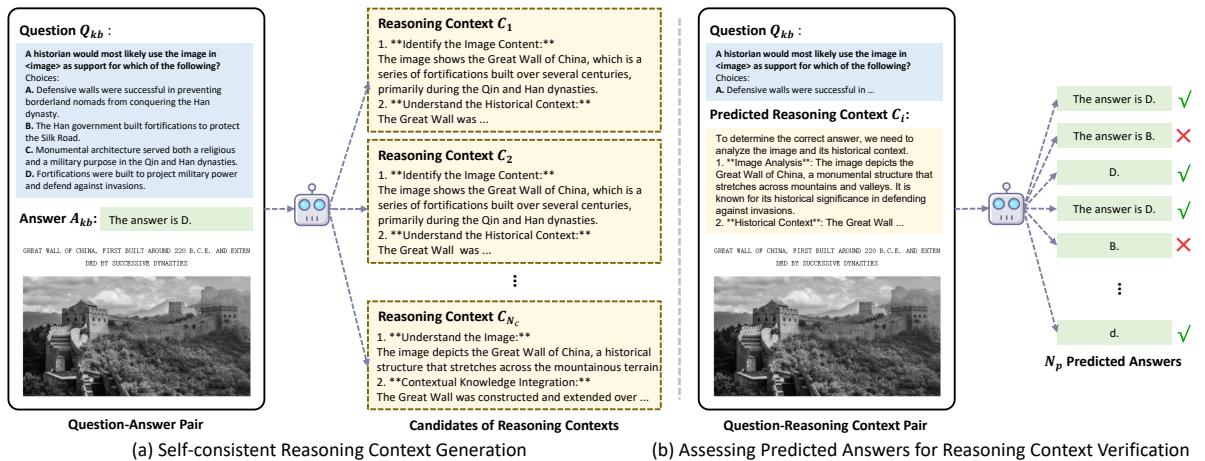

This is insufficient for complex reasoning. The RCTS framework automates the creation of “Reasoning Contexts.” It uses the LVLM itself to generate detailed explanations for the data it already has.

How it works (referencing Figure 3):

- Generation: The model looks at a Question-Answer pair from the training set and generates several candidate “thought processes” (Reasoning Contexts) that explain how to get from the question to the answer.

- Self-Consistent Verification: The system then tests these candidates. It feeds the question plus the generated context back into the model. If the model predicts the correct ground-truth answer using that context, the context is deemed valid.

- Selection: The reasoning context that leads to the highest confidence in the correct answer is saved into the knowledge base.

Now, when the system retrieves an example later, it doesn’t just pull a raw QA pair; it pulls a “mini-tutorial” on how to solve that specific type of problem.

2. Hybrid Retrieval

With a supercharged knowledge base ready, the next step is retrieval. Since we are dealing with Vision-Language models, relying on text search alone is not enough.

The authors employ a hybrid embedding strategy. They use:

- A Text Encoder to understand the semantic meaning of the question.

- A Vision Encoder to understand the content of the image.

These two representations are concatenated (joined together) to form a unified query. The system compares the user’s query against the knowledge base to find the top \(N\) most similar examples. However, similarity scores are imperfect. The “most similar” image might be misleading. This brings us to the most complex and impactful part of the paper.

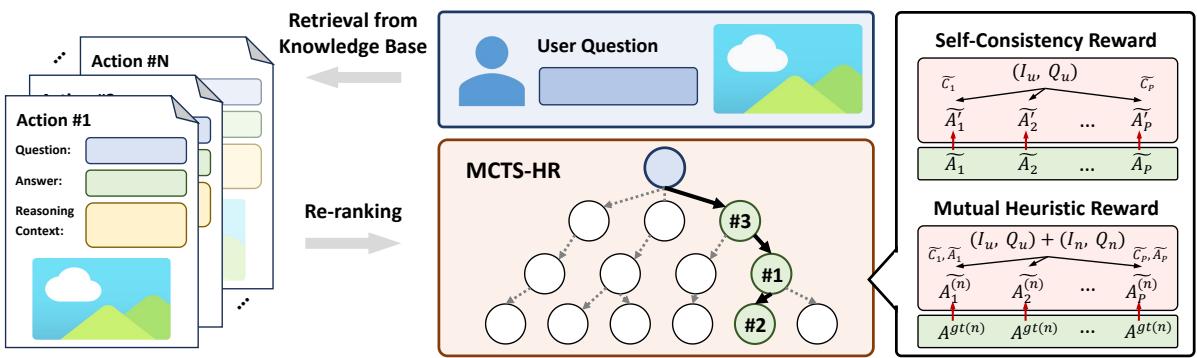

3. Re-ranking via Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

In traditional RAG, you might take the top 3 retrieved examples and feed them to the model. But what if the 4th example is actually much better than the 1st? What if the 1st example is actually a trick question that confuses the model?

To solve this, the authors treat the selection of examples as a decision-making game and solve it using Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). MCTS is the same algorithm famously used by AlphaGo to master the game of Go.

The Tree Structure

In this “game,” the goal is to construct the perfect prompt context.

- Root: The user’s original query.

- Actions: Choosing a specific retrieved example to add to the context.

- Nodes: A sequence of selected examples.

The Search Process

The algorithm performs four main steps iteratively:

- Selection: It looks at the current tree of possibilities and picks a path that balances exploring new examples and exploiting known good ones.

- Expansion: It adds a new example (action) to the sequence.

- Simulation: It runs the LVLM with the selected sequence of examples to see what happens.

- Backpropagation: It updates the “score” of that sequence based on how well the model performed.

The Secret Sauce: Heuristic Rewards

How does the MCTS know if a sequence of examples is “good” if we don’t know the answer to the user’s question yet? This is where the authors introduce Heuristic Rewards. Since we can’t check the answer directly, we check for consistency.

They use two types of rewards:

Self-Consistency Reward (\(Q_S\)): The system generates an answer using the chosen examples. Then, it uses the predicted answer and the reasoning context to generate more answers. If the model keeps generating the same answer consistently, the context is considered high-quality.

Mutual Heuristic Reward (\(Q_M\)): This is a brilliant “sanity check.” If the retrieved examples are truly helpful, they should help the model answer other questions correctly too. The system takes the current selected examples and tries to use them to solve other problems from the database (where the answer is known). If the current examples help solve those reference problems, they are likely robust and helpful for the user’s problem too.

The final score for a set of examples is a weighted combination of these two rewards.

Experiments and Results

Does adding all this complexity—reasoning contexts and tree search—actually pay off? The researchers tested RCTS on several challenging datasets:

- ScienceQA: Science questions with multimodal context.

- MMMU: A massive benchmark covering college-level subjects (Art, Business, Medicine).

- MathV: A dataset specifically for mathematical reasoning with visuals.

Quantitative Performance

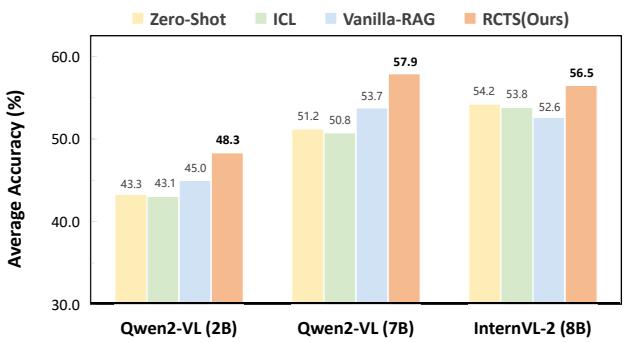

The results show a clear victory for RCTS over standard methods.

As seen in Figure 1, RCTS (the orange bars) consistently outperforms:

- Zero-Shot: Asking the model without examples (Yellow).

- ICL: Standard In-Context Learning (Green).

- Vanilla-RAG: Standard retrieval without the tree search or reasoning contexts (Blue).

The improvement is particularly striking on MathV (Mathematical Visual reasoning). For the Qwen2-VL (7B) model, RCTS jumped from roughly 53.7% (Vanilla-RAG) to 57.9%. In the world of competitive AI benchmarks, a 4% gain on complex reasoning tasks is significant.

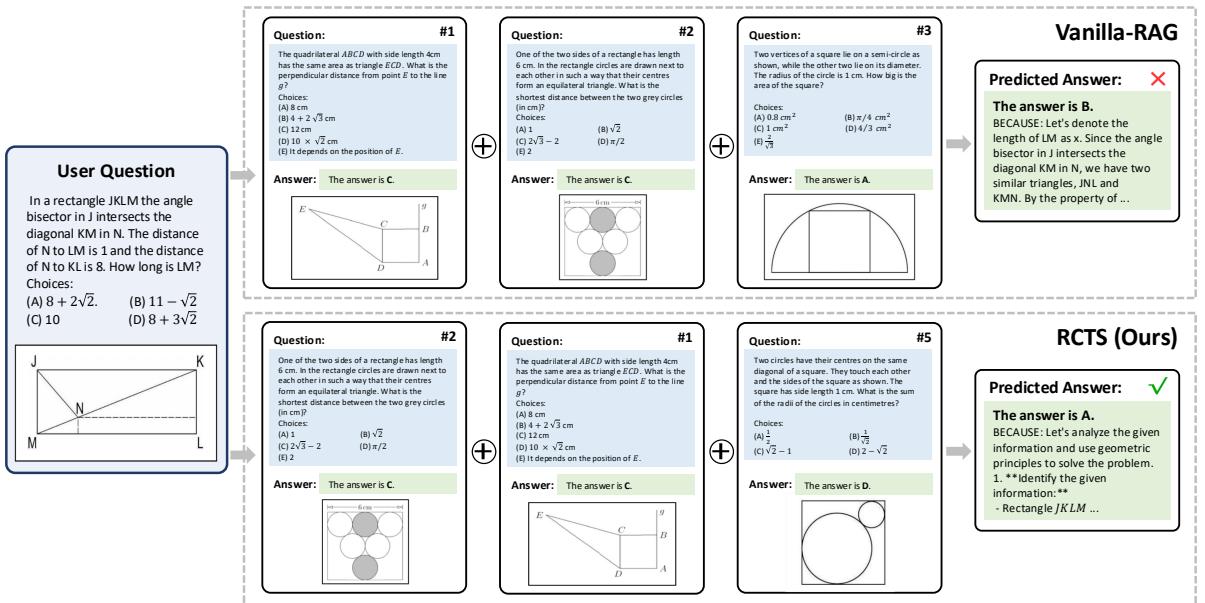

Qualitative Analysis: Why RCTS Wins

Numbers are great, but let’s look at an actual example to see the difference in behavior.

In Figure 6, we see a geometry problem asking for the length of a segment in a rectangle.

- Vanilla-RAG (Top Right): It retrieved examples that were somewhat relevant geometrically but didn’t guide the correct logic. The model hallucinated a wrong explanation (“Let’s denote…”) and picked the wrong answer (B).

- RCTS (Bottom Right): The MCTS process filtered out the confusing examples and prioritized ones that fostered clear, step-by-step geometric reasoning. Consequently, the model correctly analyzed the distances and derived the correct answer (A).

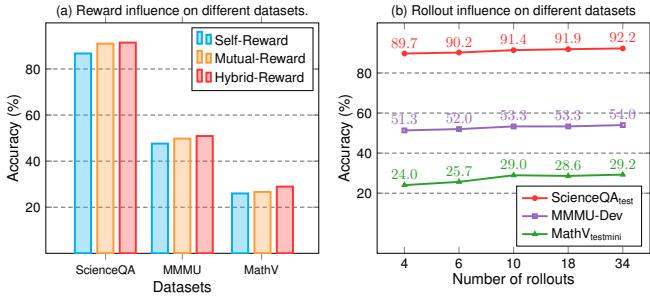

Do we really need both parts? (Ablation Studies)

You might wonder: is the improvement coming from the Reasoning Contexts or the Tree Search?

The authors performed an ablation study (breaking the model apart to test components). Figure 5(a) reveals that using Hybrid Rewards (Red bars)—combining both Self-Consistency and Mutual rewards—performs better than using either one alone.

Furthermore, Table 4 (referenced in the paper) confirms that:

- Using only MCTS improves results.

- Using only Reasoning Contexts improves results.

- Using both together yields the highest performance.

This confirms that high-quality data (Reasoning Contexts) and high-quality selection (MCTS) are synergistic.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Re-ranking Reasoning Context with Tree Search” (RCTS) framework represents a mature step forward for multimodal AI. It acknowledges that simply having access to information (Retrieval) isn’t enough; the AI needs to be shown how to think about that information.

By automating the creation of reasoning chains and using a game-theoretic approach (MCTS) to select the best “teaching examples,” RCTS transforms LVLMs from simple pattern matchers into more robust reasoners.

Key Takeaways:

- Context Matters: Providing the “thought process” alongside an answer is far more valuable than the answer alone.

- Selection is Key: The “most similar” example isn’t always the most helpful. We need intelligent search algorithms to determine which examples actually aid reasoning.

- Self-Correction: Using consistency checks allows the model to grade its own potential inputs before committing to an answer.

As LVLMs continue to grow in size and capability, frameworks like RCTS will be essential in bridging the gap between raw knowledge and true understanding, ensuring that AI can handle the complex, nuanced visual world we live in.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2506.07785/images/cover.png)