Introduction

We are currently witnessing a golden age of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). From GPT-4V to Gemini, these models promise a future where Artificial Intelligence can perceive the world just as humans do—integrating text, images, and audio into a seamless stream of understanding. We often assume that because a model can see an image, it fully understands it.

However, if you push these models slightly beyond surface-level description, cracks begin to appear. Ask a standard MLLM to explain the subtle sarcasm in a movie scene or the micro-expression on a poker player’s face, and it often resorts to hallucination or generic guesswork.

Why does this happen? Why do models capable of passing the bar exam fail to recognize that a character in The Godfather is about to cry?

The answer lies in a phenomenon researchers have termed the Deficit Disorder Attention (DDA) problem. In this post, we will deconstruct a fascinating new paper, MODA: MOdular Duplex Attention, which diagnoses this issue and prescribes a novel architectural cure. We will explore how separating “self” from “interaction” in neural networks allows AI to master fine-grained perception, complex cognition, and even emotion understanding.

The Diagnosis: Attention Deficit Disorder in MLLMs

To understand the solution, we must first understand the pathology. Most modern MLLMs are built by stitching a visual encoder (like a digital eye) onto a massive Large Language Model (the brain). The “glue” holding them together is the attention mechanism.

The researchers discovered that while this architecture works for general tasks, it suffers from a critical imbalance.

The Bias Toward Text

LLMs are pre-trained on vast oceans of text. When you introduce visual tokens (encoded image patches) into the mix, the model’s attention mechanism naturally gravitates toward what it knows best: the text.

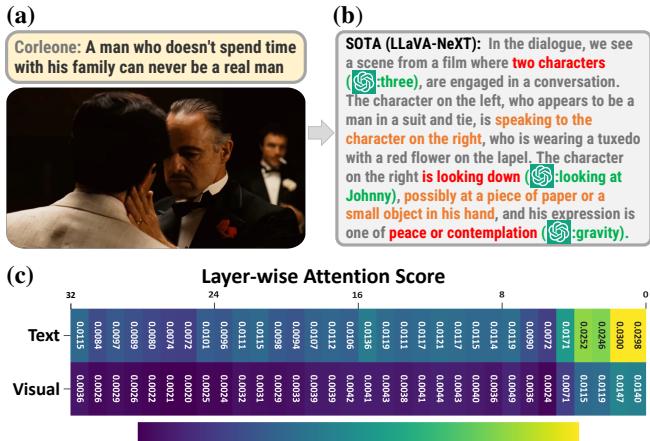

As illustrated in Figure 1 above, existing state-of-the-art models often miss fine-grained visual cues. In the example from The Godfather, the model fails to track the specific visual interactions between characters, leading to a “hallucinated” explanation of the scene. It invents details because it isn’t paying enough attention to the actual image pixels.

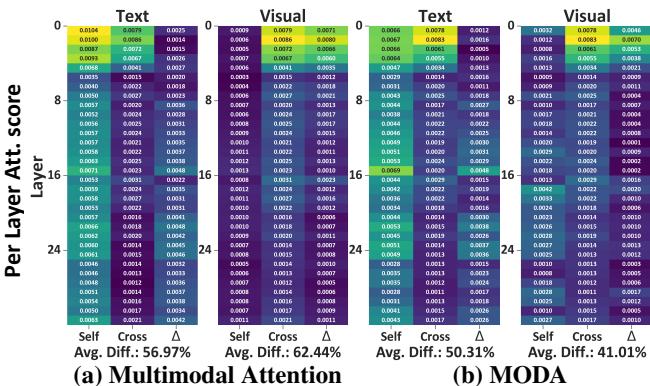

The Layer Decay Phenomenon

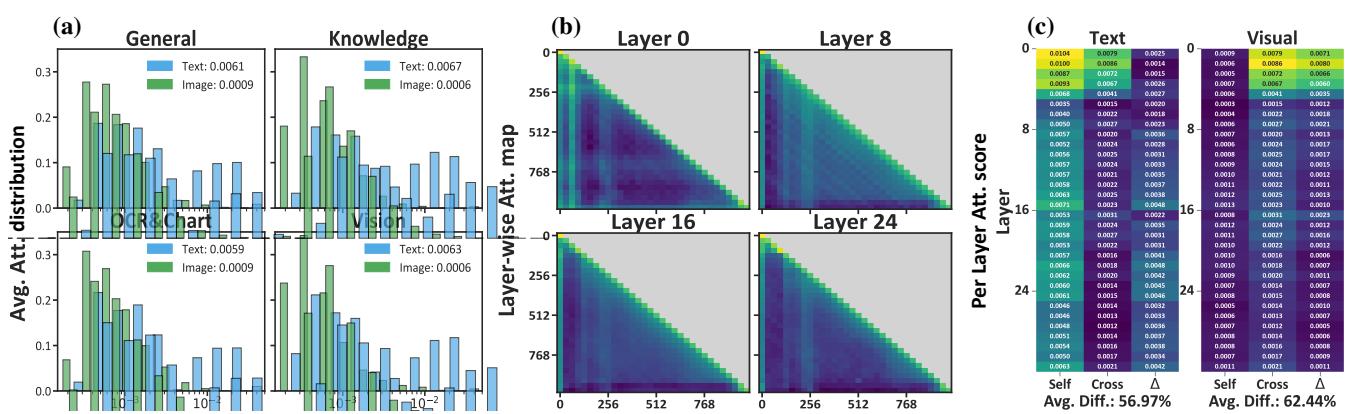

The problem gets worse as you go deeper into the neural network. A Transformer model is composed of many layers stacked on top of each other. The researchers analyzed the attention scores—the numerical values representing how much the model focuses on different inputs—across these layers.

In Figure 2, specifically panels (b) and (c), we see a stark reality. In the shallow (early) layers, there is some cross-modal interaction. But as the information propagates to deeper layers (where complex reasoning happens), the attention paid to visual tokens collapses.

This is the Deficit Disorder Attention (DDA) problem. The model’s focus on the image decays layer-by-layer, exponentially. By the time the model tries to form a high-level conclusion (like “is this man angry or sad?”), it has effectively stopped looking at the image and is relying almost entirely on the text prompt.

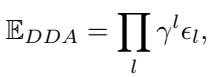

Mathematically, the researchers describe this cumulative error (\(\mathbb{E}_{DDA}\)) as the product of layer-wise alignment errors (\(\epsilon_l\)) and a decay factor (\(\gamma\)):

If \(\gamma \neq 1\) (which is the case when text dominates), the error grows exponentially with depth. The result? An AI that is functionally blind to subtle visual details in its reasoning layers.

The Solution: MOdular Duplex Attention (MODA)

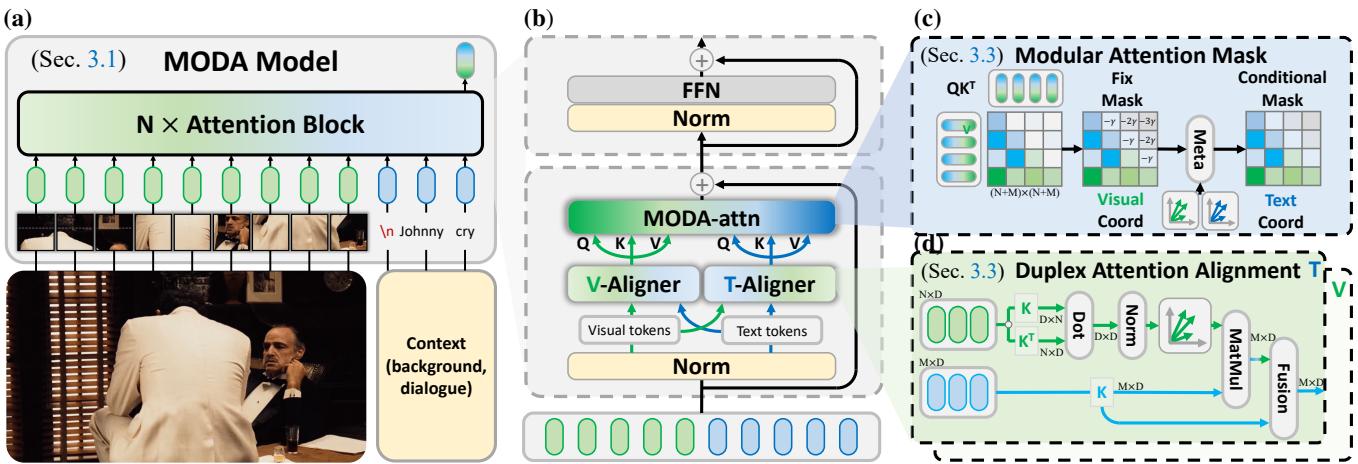

To fix this, the authors propose MODA. The core philosophy of MODA is decoupling. Instead of letting text and vision fight for dominance in a single messy attention pool, MODA splits the process into two distinct, managed streams that are carefully realigned.

The architecture introduces a strategy called “Correct-after-Align.” It consists of two main components working in tandem:

- Duplex Attention Alignment: Ensuring modalities speak the same language.

- Modular Attention Mask: Enforcing a balanced flow of information.

Let’s break down the architecture shown below.

1. Duplex Attention Alignment

In a standard transformer, visual tokens and text tokens are just thrown together. Because they come from different distributions (one from a vision encoder, one from text embeddings), they are misaligned.

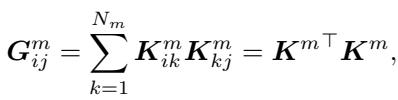

MODA introduces a Duplex (V/T)-Aligner (visible in Figure 3d). The goal is to map tokens from one modality into the space of the other before they interact. To do this efficiently, the authors utilize the Gram Matrix.

In linear algebra, a Gram matrix represents the inner products of a set of vectors. It captures the geometric relationship or the “style” of the feature space. By computing the Gram matrix of the visual tokens, the model extracts the “basis vectors” of the visual space.

Using this Gram matrix, MODA projects the tokens from the other modality (e.g., text) into this shared space:

This creates a “shared dual-modality representation space.” It’s akin to a translator who doesn’t just translate words (text) but also translates cultural context (visual style) so that the conversation (attention) is fluid. This ensures that when the text attends to the image, it’s doing so in a mathematically aligned vector space.

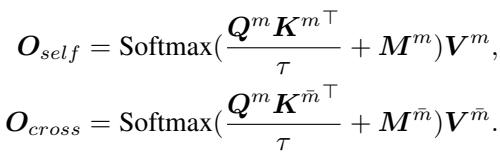

2. Modular Attention Mask

Even with aligned features, the “text bias” could still cause the model to ignore images in deeper layers. To prevent this, MODA implements a strict Modular Attention Mask.

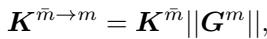

Standard attention allows every token to look at every other token (\(N \times N\)). MODA splits this. It explicitly separates:

- Self-Modal Attention: Text looking at text; Image looking at image.

- Cross-Modal Attention: Text looking at image; Image looking at text.

By separating these calculations, the model can apply different masking rules to each. The authors introduce a “pseudo-attention” mechanism (Equation 14 below) where excess attention values are stored and managed, rather than being discarded or allowed to dominate.

This structure enforces a “modality location prior.” It forces the model to maintain active links between text and vision across all layers, preventing the layer-wise decay we saw earlier.

Experimental Results

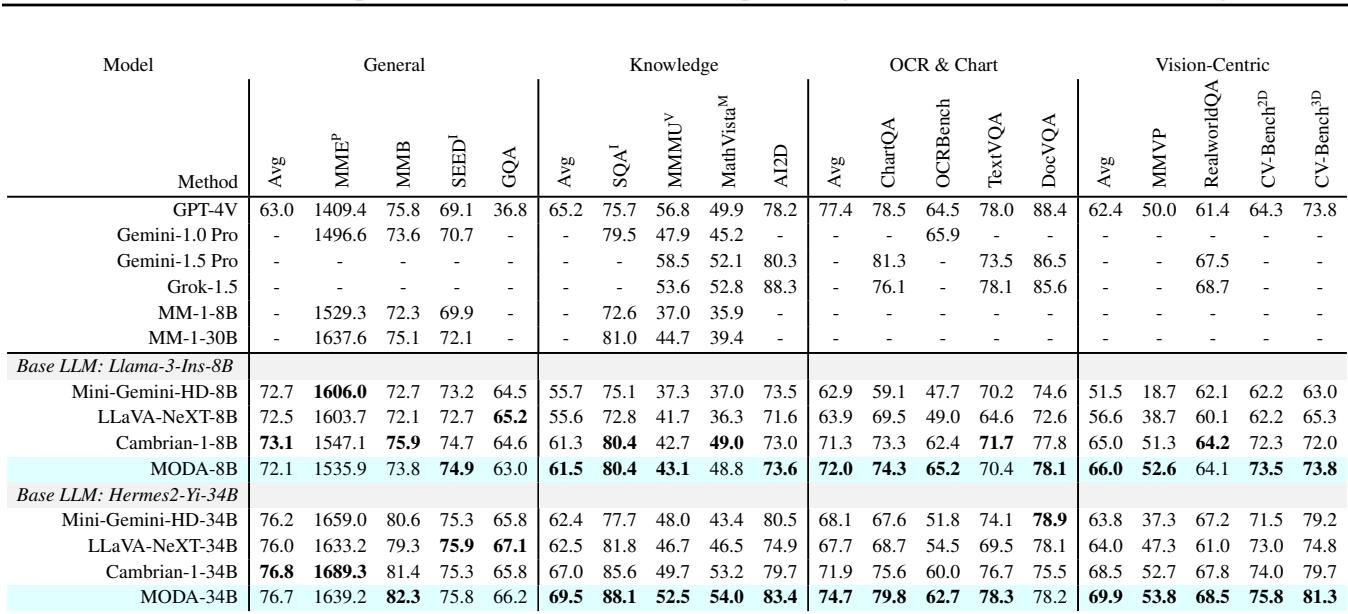

The theory sounds solid, but does it work? The researchers tested MODA on 21 benchmarks covering three distinct capabilities: Perception, Cognition, and Emotion.

1. Perception: Seeing the Details

Perception tasks ask straightforward questions about visual content (e.g., “What is written on this sign?” or “How many people are in the boat?”).

As shown in Table 2, MODA consistently outperforms models of similar size (like LLaVA-NeXT and Cambrian-1). Notably, look at the OCR & Chart and Vision-Centric columns. These tasks require precise attention to small visual details. MODA-8B beats LLaVA-NeXT-8B by significant margins here, proving that the duplex alignment helps the model “read” images more accurately.

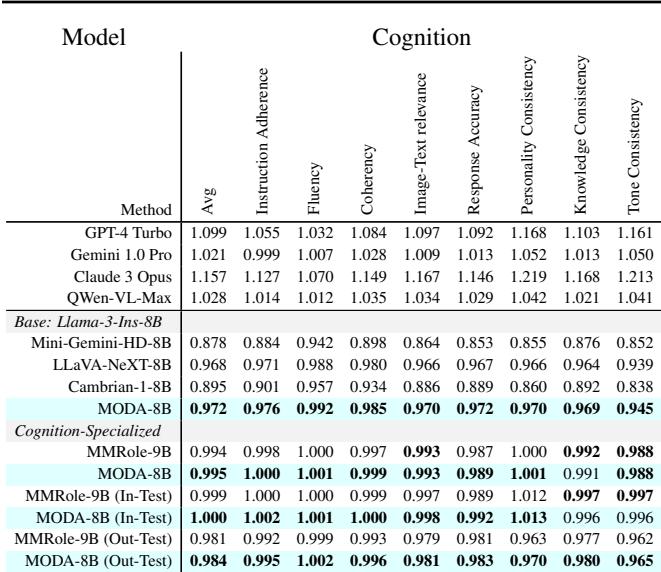

2. Cognition and Role-Playing

Cognition involves higher-order reasoning. Can the model adopt a persona? Can it maintain consistency? The researchers used the MMRole benchmark to test this.

In Table 3, MODA achieves the highest average score (0.995) among 8B models, even rivaling the proprietary Claude 3 Opus in some metrics. It excels in Instruction Adherence and Personality Consistency, suggesting that by better integrating visual context, the model stays “in character” more effectively.

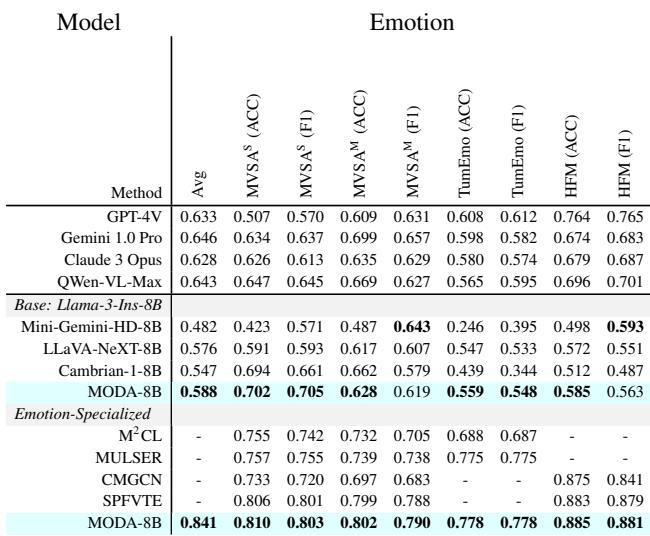

3. Emotion Understanding

This is perhaps the most difficult task for AI. Emotion is often conveyed through subtle cues—a raised eyebrow, a specific color palette, or the juxtaposition of objects.

Table 4 demonstrates MODA’s superiority in affective computing. On the TumEmo and HFM (Hierarchical Fusion Model) datasets, which test for complex emotions and sarcasm, MODA outperforms general-purpose MLLMs and even beats specialized models designed specifically for emotion recognition.

Why It Works: Analyzing the Attention

The researchers revisited the “heatmaps” from the introduction to verify their hypothesis.

Figure 4 confirms the fix. In panel (a), we see the baseline model’s visual attention (right side of the chart) fading into darkness in deep layers. in panel (b), MODA maintains high-intensity attention (yellow/green) on visual tokens all the way from Layer 8 to Layer 24. The “Deficit Disorder” has been effectively treated.

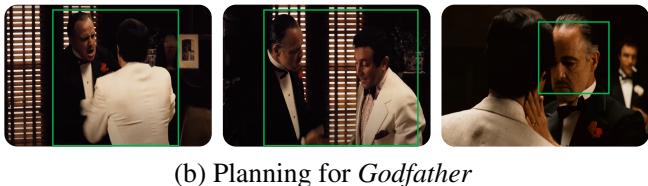

Case Study: The Godfather

Numbers are great, but qualitative examples show us how the model thinks. The paper provides a compelling case study using scenes from the movie The Godfather.

In this scenario, the user asks the model to interpret the scene and then plan a conversation as if it were the Godfather (Don Corleone).

The Insight: In Figure 6, notice the depth of MODA’s analysis. A standard model might just see “two men talking.” MODA, however, identifies the “stern demeanor” and the “power dynamics.” It perceives the micro-expressions of concern on the Godfather’s face.

The Plan: When asked to proceed with the conversation, MODA simulates the character’s strategic thinking. It doesn’t just generate generic text; it plans a response that combines empathy (“It’s a lot to take in”) with the practical leadership expected of the character (“we’ll figure it out together”). This requires synthesizing the visual emotional state of the other character (Johnny crying) with the persona of the Godfather.

Conclusion

The development of MODA highlights a crucial lesson in the evolution of Multimodal AI: Scale is not enough. simply making models bigger or training them on more data doesn’t automatically solve structural inefficiencies like the attention deficit.

By identifying the specific mechanical failure—the decoupling of visual attention in deep layers—and engineering a targeted solution via Duplex Alignment and Modular Masking, the researchers have unlocked a new level of granularity in AI understanding.

MODA moves us closer to agents that don’t just “process” images, but actually “perceive” the world—recognizing the humor in a meme, the sarcasm in a post, or the subtle grief in a movie scene. As MLLMs continue to integrate into our daily lives, this ability to understand the nuance of human experience will be the difference between a robotic assistant and a truly intelligent companion.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2507.04635/images/cover.png)