Artificial Intelligence has a trust problem. As Deep Learning models, particularly Transformers, continue to dominate fields ranging from movie sentiment analysis to complex scientific classification, they have become increasingly accurate—and increasingly opaque. We often know what a model predicts, but rarely why.

If a model flags a financial transaction as fraudulent or diagnoses a medical scan as positive, “because the computer said so” is no longer an acceptable justification. We need rationales—highlights of the input text that explain the decision.

In this post, we are diving deep into a paper by Brinner and Zarrieß that proposes a novel, elegant solution to this problem: the Rationalized Transformer Predictor (RTP). They introduce a method that allows a single model to classify text and highlight the evidence for that classification in one go, using a clever mathematical trick called end-to-end differentiable self-training.

If you are a student of machine learning looking to understand the bleeding edge of Explainable AI (XAI), grab a coffee. We are going to break down how to turn a black box into a glass house.

The Landscape of Explainability

To understand why the RTP is such a breakthrough, we first need to look at how researchers have traditionally tried to extract explanations from neural networks. Generally, there are two camps: Post-Hoc Explanations and Rationalization Games.

1. Post-Hoc Explanations

This is the “after the fact” approach. You take a fully trained, standard classifier, run an input through it, and then use a separate algorithm (like LIME or Integrated Gradients) to poke and prod the model to see which words triggered the output. While useful, these methods can be slow and computationally expensive. More importantly, they are approximations; they are an external observer’s best guess at what the model thought, not necessarily a faithful representation of the internal reasoning.

2. Rationalized Classification (The Game Approach)

This is the “built-in” approach. Here, the goal is to architect the model so it must provide a rationale to make a prediction. Traditionally, this is framed as a cooperative game between multiple models:

- The Selector (Generator): Reads the text and selects a subset of words (the rationale).

- The Predictor: Takes only those selected words and tries to guess the label.

If the Predictor guesses correctly, the Selector gets a reward. The logic is sound: if the Predictor can classify the text using only the selected words, those words must be the important ones.

The Problem with the Game

While the game approach sounds perfect, it is plagued by training nightmares.

- Stochastic Sampling: To pick a discrete set of words (keep vs. delete), the model has to make binary choices. This sampling process breaks the gradient chain (you can’t differentiate through a coin flip), forcing researchers to use reinforcement learning techniques like REINFORCE, which are notoriously unstable.

- The Dominant Selector: sometimes the Selector gets too smart. It might encode the answer in a trivial way (e.g., selecting the first token implies “positive”, the second implies “negative”) so the Predictor doesn’t actually learn the task—it just learns to read the Selector’s cheat codes.

- Interlocking Dynamics: Since two distinct models are training simultaneously, they can get stuck in loops where neither improves.

The authors of this paper looked at these complex multi-player games and asked: Why do we need two or three different models? Can’t one model do it all?

The Core Method: The Rationalized Transformer Predictor (RTP)

The researchers propose a paradigm shift. Instead of a complex game between a Selector and a Predictor, they use a single Transformer model that performs both tasks simultaneously.

1. The Unified Architecture

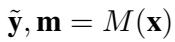

The RTP is a standard Transformer (like BERT) that accepts an input sequence \(\mathbf{x}\). In a single forward pass, it outputs two things:

- The Classification (\(\tilde{\mathbf{y}}\)): The probability of the class labels.

- The Rationale Mask (\(\mathbf{m}\)): A score between 0 and 1 for every token, indicating how important it is for that specific class.

This is formalized in the equation below:

This simplicity is deceptive. By outputting the mask alongside the prediction, the model is exposing its own attention mechanism to optimization. But how do we ensure the mask is actually meaningful? We need to parameterize it correctly.

2. Parameterizing the Mask

A raw neural network output can be noisy. If we just let the model pick individual words, it might pick scattered tokens like “the”, “and”, or punctuation that happen to carry statistical noise. Human rationales are usually spans of text—phrases or sentences.

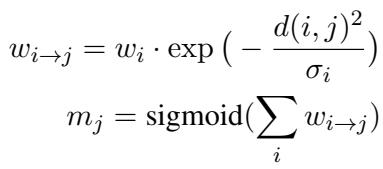

To enforce this, the authors use a specific parameterization. Instead of predicting a mask value directly, the model predicts an influence weight (\(w\)) and a width (\(\sigma\)) for every token. These values determine how much a token contributes to the mask of its neighbors.

In the equation above:

- \(d(i, j)\) is the distance between token \(i\) and token \(j\).

- The exponential function acts like a Gaussian blur. A high score on one word “bleeds” over to its neighbors, naturally creating coherent spans of text rather than jagged, isolated points.

- The final mask \(m_j\) is the sigmoid of the sum of these influences, ensuring values stay between 0 and 1.

3. End-to-End Differentiable Self-Training

Here is the genius part of the paper. How do you train the mask without the unstable sampling mentioned earlier?

The authors use the mask generated by the model to create two altered versions of the input:

- The Rationalized Input (\(\mathbf{x}^c\)): The original text blended with the mask. This keeps the “important” info.

- The Complement Input (\(\overline{\mathbf{x}}^c\)): The original text blended with the inverse of the mask. This keeps only the “unimportant” info.

Crucially, rather than deleting words (which is discrete and non-differentiable), they use linear blending. They mix the word embedding with a generic “background” embedding based on the mask value.

Because this blending is mathematical (multiplication and addition), the gradients can flow right through it. The model can learn exactly how much to adjust the mask to minimize loss.

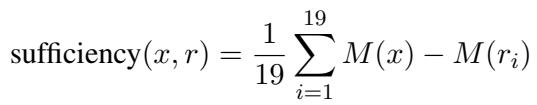

4. The Loss Function: Sufficiency and Comprehensiveness

Now, how does the model learn what makes a “good” rationale? The authors define a training objective based on two intuitive concepts:

- Sufficiency: If the rationale is good, the model should be able to classify the Rationalized Input (\(\mathbf{x}^c\)) correctly.

- Comprehensiveness: If the rationale effectively captured all the evidence, the model should fail to classify the Complement Input (\(\overline{\mathbf{x}}^c\)).

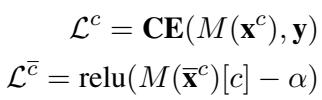

This logic is codified in the loss functions below:

- \(\mathcal{L}^c\) is the standard Cross-Entropy (CE) loss on the rationalized input. We want to minimize this (make the prediction good).

- \(\mathcal{L}^{\bar{c}}\) looks at the complement. We want the probability of the correct class \(c\) to drop below a threshold \(\alpha\). We want the model to be “ignorant” when the rationale is removed.

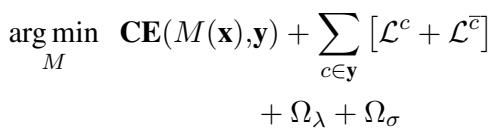

5. Putting It All Together

The final training objective combines the standard classification loss on the full text, the self-training losses for the rationales, and regularization terms (to encourage sparsity and smoothness).

- \(\Omega_{\lambda}\) encourages the mask to be sparse (don’t highlight the whole text).

- \(\Omega_{\sigma}\) encourages the mask to be smooth (select continuous spans).

By optimizing this single equation, the RTP learns to classify text while simultaneously identifying exactly which parts of the text are driving that classification.

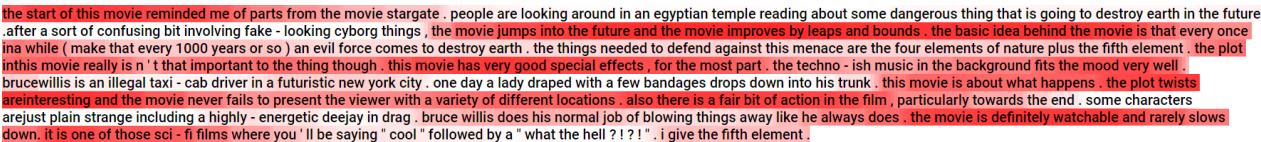

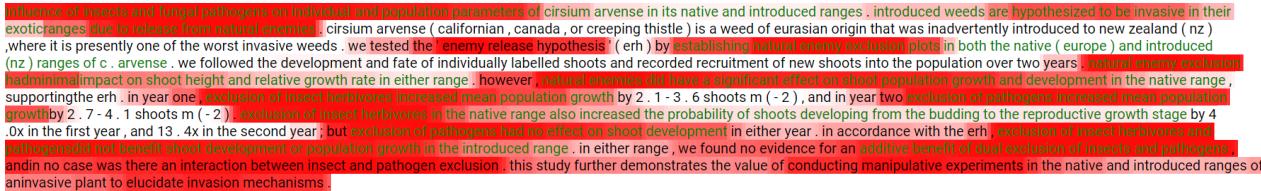

Here is an example of what the output looks like. The red highlighting represents the model’s generated mask (rationale). Notice how it selects coherent phrases like “confusing,” “fake,” and “annoying” to justify a negative sentiment.

Experiments and Results

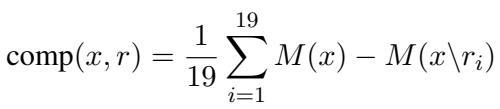

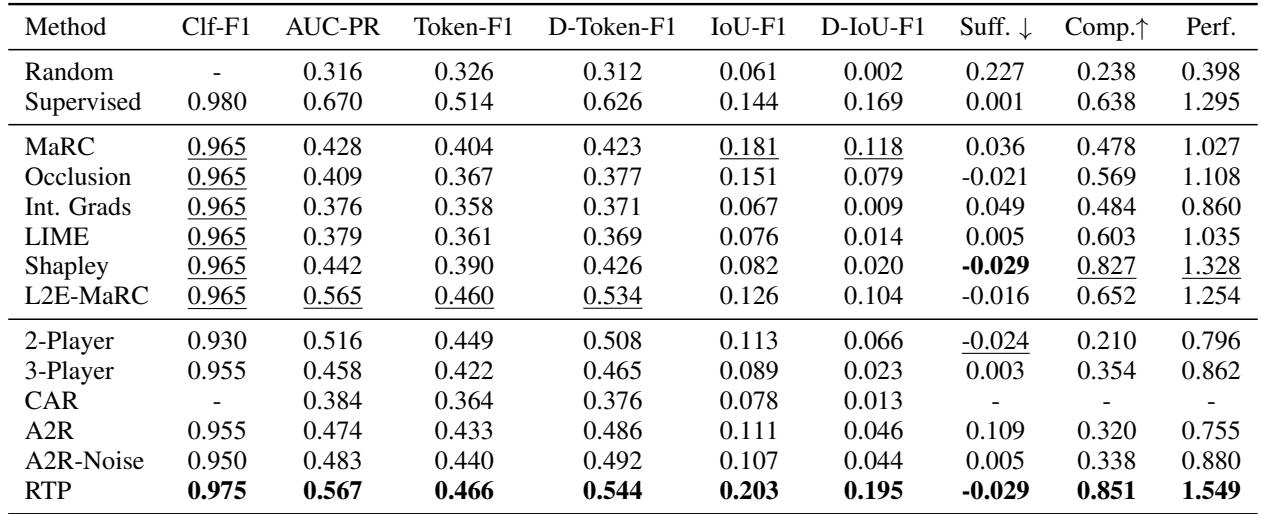

The researchers put RTP to the test against a gauntlet of baselines, including the standard 3-Player Game methods and various post-hoc explainers (like LIME and Integrated Gradients).

They used two very different datasets:

- Movie Reviews: Standard positive/negative sentiment analysis.

- INAS: A challenging scientific dataset where the model must classify abstracts based on specific biological hypotheses.

Metrics for Success

How do you grade an explanation?

- Agreement (IoU-F1): Did the model highlight the same words a human annotator did?

- Faithfulness: Does the rationale actually explain the model’s behavior?

To measure faithfulness quantitatively, they used Sufficiency and Comprehensiveness metrics:

Results on Scientific Data (INAS)

The INAS dataset is tricky because scientific language is dense. The table below shows the results.

Key Takeaways from INAS:

- RTP (Last row) achieves the highest scores in almost every category (Bolded numbers).

- Look at IoU-F1 (0.226). This measures overlap with human annotation. RTP significantly outperforms the 3-Player game (0.080) and post-hoc methods like LIME (0.082).

- The Perf. column (Overall Performance) shows RTP dominating with a score of 1.197.

Results on Movie Reviews

For the simpler movie review task, the results were equally impressive.

Key Takeaways from Movie Reviews:

- Again, RTP sweeps the board.

- The Comprehensiveness (Comp.) score is particularly high (0.851). This means when RTP removes the words it thinks are important, the model’s ability to predict the movie sentiment crashes. This proves the model is not lying; it truly relies on those words.

Visual Comparison

To visualize the alignment with human reasoning, we can look at the “Ground Truth” annotations (green text) compared to the model’s predictions. The RTP captures long, meaningful spans that align very well with what a human considers “evidence.”

Why This Matters

The Rationalized Transformer Predictor represents a maturation of Explainable AI. We are moving away from “hacky” solutions—like training multiple unstable models or trying to reverse-engineer a black box after it has already made a decision.

Instead, this paper demonstrates that explainability can be intrinsic. By making the rationale generation differentiable and part of the primary training loop, we get the best of both worlds:

- Stability: No more reinforcement learning instability.

- Performance: The model learns to focus on the signal and ignore the noise, often maintaining or even improving classification accuracy.

- Faithfulness: The rationales are mathematically tied to the prediction mechanism.

For students and researchers entering the field, the RTP highlights the power of inductive biases. By telling the model “I want you to learn spans” (via the mask parameterization) and “I want you to explain yourself” (via the complement loss), we can guide massive Transformers to be not just smarter, but more honest.

As we deploy AI into high-stakes environments like law and medicine, this honesty is not just a feature—it is a requirement.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2508.11393/images/cover.png)