In the world of machine learning, graphs are everywhere. From social networks and chemical molecules to citation maps and computer networks, we use graphs to model complex relationships. Over the last few years, Self-Supervised Learning (SSL), particularly Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL), has become the dominant method for teaching machines to understand these structures without human labeling.

But there is a flaw in the current paradigm.

Standard contrastive learning treats every single node in a graph as a unique entity. It assumes that a node is only “equivalent” to itself (or an augmented version of itself). This ignores a fundamental reality of graphs: Equivalence. In a computer network, two different servers might perform the exact same role and connect to similar devices. In a molecule, two carbon atoms might be structurally symmetrical. To a human, these nodes are “the same” in function and form. To a standard GCL model, they are completely different.

In this deep dive, we are exploring the research paper “Equivalence is All: A Unified View for Self-supervised Graph Learning.” The authors introduce GALE, a framework that argues we should stop treating every node as unique and start grouping them by their structural and attribute equivalence.

Let’s unpack how this works, why strict math makes it hard, and how the researchers solved it with a clever approximation.

1. The Core Problem: Ignoring Symmetry

To understand why the GALE framework is necessary, we first need to look at what current methods are missing.

Most modern Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) trained via contrastive learning operate on a simple principle: Instance Discrimination.

- Take a graph.

- Create two slightly different views of it (e.g., by dropping a few edges).

- Teach the model that Node A in View 1 is the same as Node A in View 2 (Positive Pair).

- Teach the model that Node A is different from Node B, Node C, and every other node (Negative Pairs).

This works well for identifying specific nodes, but it fails to capture semantic similarity.

Imagine a social network. You have two users, Alice and Bob. They don’t know each other. However, they both live in the same city, work the same job, and are the “hub” of their respective friend groups. Structurally and functionally, Alice and Bob are equivalent. A model should map them to similar representations. But standard contrastive learning pushes them apart because they are technically different instances.

The authors of this paper argue that we need to explicitly incorporate Node Equivalence into the learning process.

2. Background: What is Node Equivalence?

Before we look at the solution, we need to define the problem mathematically. The paper focuses on two specific types of equivalence: Automorphic Equivalence (Structure) and Attribute Equivalence (Features).

Automorphic Equivalence (Structure)

This is a concept from algebraic graph theory. Two nodes are automorphically equivalent if you can swap them without changing the graph’s connectivity structure.

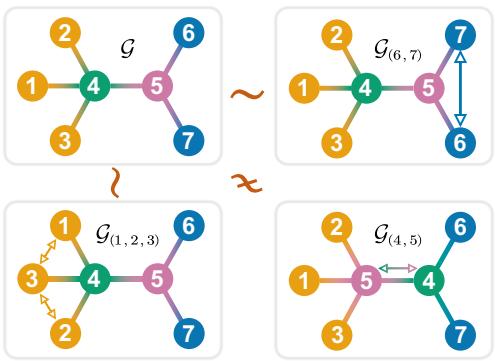

Look at Figure 1 above.

- In the top left graph (\(\mathcal{G}\)), consider nodes 6 and 7. They both connect only to node 5. If you swapped node 6 and node 7, the graph would look exactly the same. They are Automorphically Equivalent.

- Now look at nodes 4 and 5. If you swapped them (bottom right, \(\mathcal{G}_{(4,5)}\)), the connections would change drastically. Node 5 would connect to 1, 2, and 3, which it didn’t before. They are not equivalent.

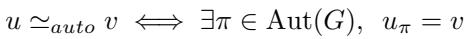

The mathematical definition of this relationship is:

This basically states that node \(u\) and node \(v\) are equivalent if there exists a permutation \(\pi\) in the graph’s automorphism group \(\operatorname{Aut}(G)\) that maps \(u\) to \(v\).

Attribute Equivalence (Features)

This is simpler. In many graphs, nodes have features (attributes) like text, age, or chemical properties. Two nodes are attribute-equivalent if their feature vectors are identical.

Why This Matters

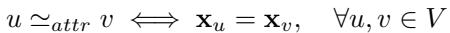

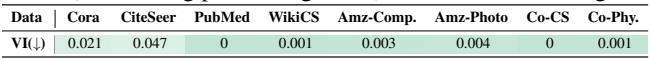

The researchers analyzed several benchmark datasets to see how common these equivalences are.

As shown in Table 1, equivalence is not a niche edge case. In the MUTAG and IMDB-B datasets, 100% of the graphs contain automorphic equivalence. In citation networks like Citeseer, nearly half of the nodes (46.2%) have a structural twin. Ignoring this means ignoring a massive amount of signal in the data.

3. GALE: The Framework

The researchers propose GALE (GrAph self-supervised Learning framework with Equivalence). The goal is to learn node representations where:

- Nodes in the same equivalence class are similar (Intra-class).

- Nodes in different classes are dissimilar (Inter-class).

The Architecture

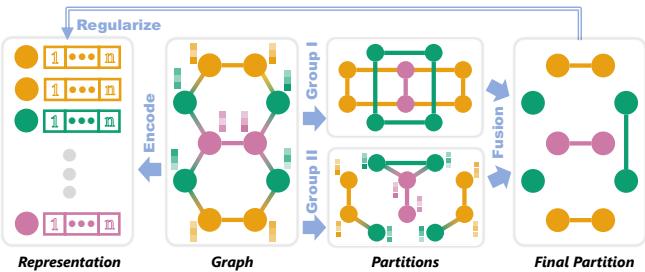

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow:

- Input: The raw graph with structure and features.

- Partitions (Top Branch): The system analyzes the graph to find “Groups.” It calculates structural equivalence (Group I) and attribute equivalence (Group II).

- Encoder (Bottom Branch): A standard GNN (like a GCN) encodes the nodes into embeddings.

- Regularization (Fusion): The partition groups act as constraints. The loss function forces the embeddings to respect the identified groups.

The Fusion Strategy

A node’s identity is defined by both its position in the network (Structure) and its intrinsic properties (Attributes). To capture this, GALE fuses the two partitions using an Intersection approach.

This formula means that for two nodes to be in the same final “Fused Class” (\(F\)), they must be both structurally equivalent (\(C_i\)) and attribute equivalent (\(D_j\)). This creates a refined, high-confidence grouping of nodes.

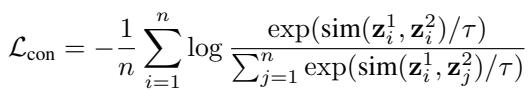

The Loss Function

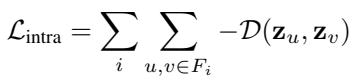

Once the groups are defined, how does the model learn? The authors design a specific loss function divided into two parts.

1. Intra-class Loss (Pull Together) This term looks at every pair of nodes \((u, v)\) inside the same equivalence class \(F_i\) and maximizes the similarity of their embeddings (\(\mathbf{z}\)).

2. Inter-class Loss (Push Apart) This term looks at pairs of nodes from different classes and minimizes their similarity.

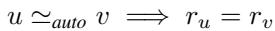

3. Total Equivalence Loss The final objective is simply the sum of the two.

4. The Engineering Challenge: Approximation

If you are a computer science student, you might have paused at the mention of “calculating graph automorphisms.” Why? Because the Graph Isomorphism problem is famously difficult. Exact automorphism detection is NP-hard in the worst case. It is computationally impossible to run exact algorithms (like nauty or bliss) on massive graphs with millions of nodes.

Furthermore, real-world data is noisy. Two nodes might be almost identical in attributes, but a 0.01% difference would put them in different classes under strict definitions.

To make GALE practical, the authors introduce Approximate Equivalence Classes.

Approximating Structure with PageRank

Instead of calculating exact orbits, the authors use PageRank. PageRank assigns a score to a node based on its structural importance (essentially, the probability of a random walker landing on it).

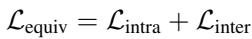

The intuition is defined in this relationship:

If two nodes are automorphically equivalent (\(u \simeq_{auto} v\)), they must have the same PageRank score (\(r_u = r_v\)).

Note: The reverse is not always true (two non-equivalent nodes can have the same score), but it is a very strong, computationally cheap proxy.

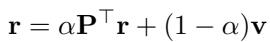

The PageRank vector is calculated iteratively:

This operation is linear with respect to the number of edges, \(O(m)\), making it vastly faster than exact automorphism detection.

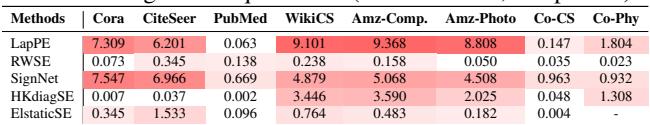

Does this approximation actually work? The authors tested the alignment between true automorphism classes and PageRank classes using “Variation of Information” (VI), where 0 means perfect alignment.

Table 2 shows that on datasets like PubMed and Coauthor-CS, the alignment is nearly perfect (VI \(\approx\) 0). The approximation captures the structural symmetries almost as well as the exact (and slow) algorithms.

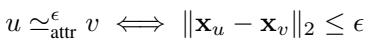

Approximating Attributes with Distance Thresholds

For node features, strict equality is replaced by a distance threshold \(\epsilon\).

If the Euclidean distance between two feature vectors is smaller than \(\epsilon\), they are treated as equivalent. This adds robustness to noise.

5. Theoretical Connections

The paper provides a fascinating critique of existing methods through the lens of equivalence.

GALE vs. Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL)

The authors prove that standard GCL is actually just a degenerate form of GALE.

In standard GCL (like the loss shown below), the model tries to match a node to itself.

From GALE’s perspective, GCL assumes that the size of every equivalence class is exactly 1. It ignores the existence of other equivalent nodes in the graph. GALE generalizes GCL by allowing the “positive set” to include distinct nodes that happen to be equivalent.

GALE vs. MPNNs and Transformers

- Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs/GCNs): MPNNs aggregate neighbors. If two nodes have identical neighborhoods (equivalence), MPNNs will naturally give them similar representations. However, MPNNs suffer from over-smoothing—as you add layers, all nodes start looking the same, even non-equivalent ones.

GALE fixes this by explicitly enforcing the Inter-class loss (pushing non-equivalent nodes apart).

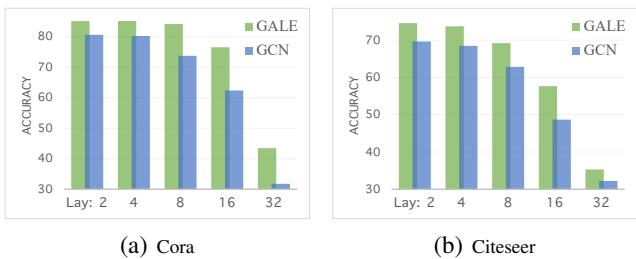

Figure 3 demonstrates this beautifully. As the number of layers increases (x-axis), the accuracy of a standard GCN (blue) plummets due to over-smoothing. GALE (green) maintains high accuracy even at 32 layers because the loss function forces distinct classes to remain distinct.

- Graph Transformers: These rely on Positional Encodings (PE) to understand structure. The authors found that most popular PE methods (like Laplacian PE or Random Walk PE) do not respect automorphic equivalence.

Table 3 shows high Variation of Information for methods like LapPE, meaning nodes that are structurally identical are often assigned different positional encodings, confusing the model.

6. Experiments and Results

Does adding equivalence constraints actually improve performance? The authors tested GALE on both Graph Classification and Node Classification tasks.

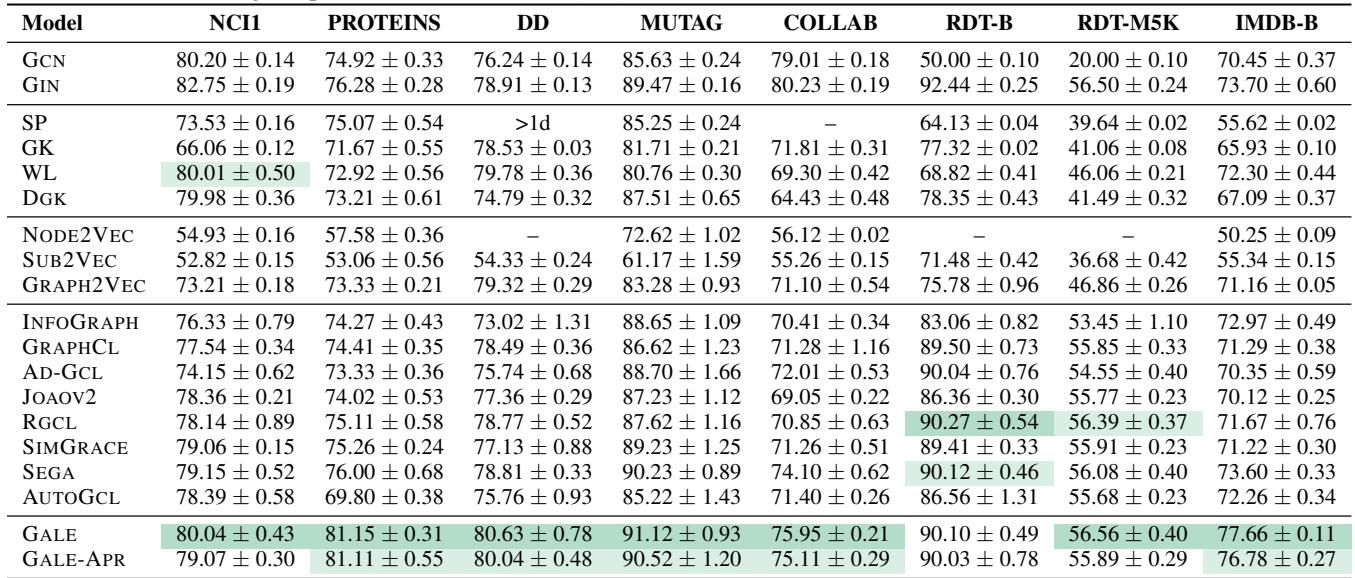

Graph Classification

Here, the goal is to classify an entire graph (e.g., is this molecule toxic?).

In Table 5, GALE (and its approximate version GALE-APR) consistently outperforms unsupervised baselines (shaded green) and even beats supervised methods like GIN on several datasets (like IMDB-B).

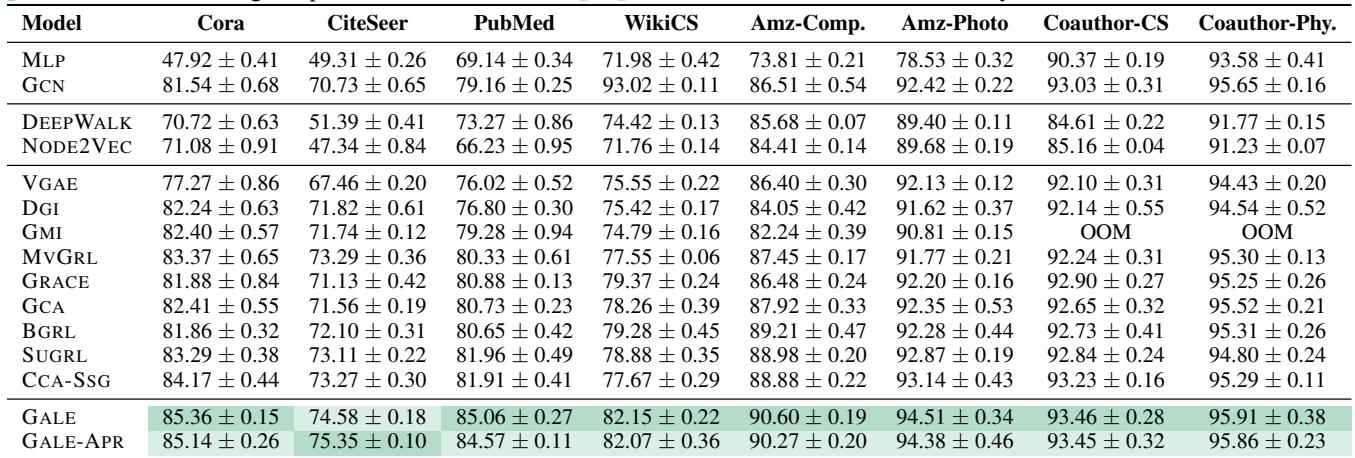

Node Classification

Here, the goal is to classify specific nodes (e.g., what is the research topic of this paper in a citation network?).

Table 6 shows GALE achieving state-of-the-art results among unsupervised methods. On the PubMed dataset, GALE reaches 85.06% accuracy, beating the previous best (SUGRL) by over 3% and even outperforming the supervised GCN baseline (79.16%).

Robustness of Approximations

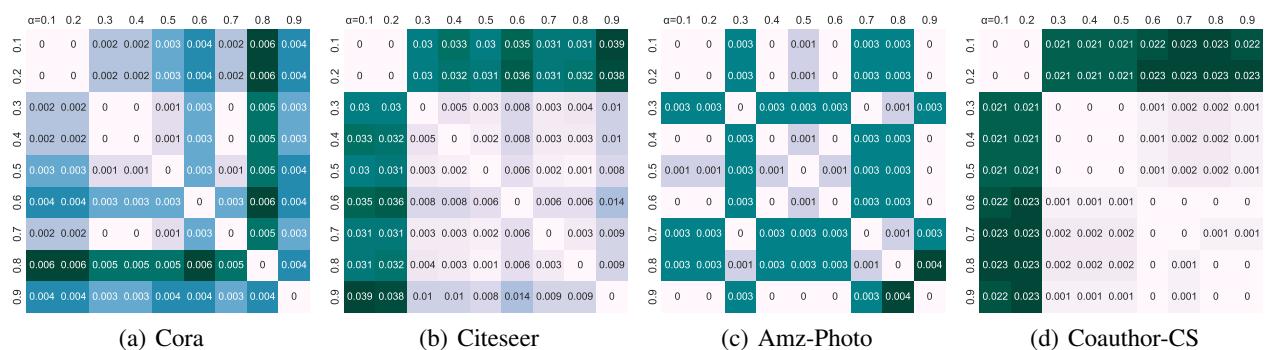

Finally, one might wonder if the PageRank approximation is sensitive to the damping factor \(\alpha\) (the probability of teleporting in the random walk).

Figure 4 displays heatmaps comparing partitions generated with different \(\alpha\) values. The very low values (mostly dark/black) indicate that the resulting equivalence classes are stable regardless of the hyperparameter choice. This makes GALE-APR highly reliable in practice.

7. Conclusion

The paper “Equivalence is All” challenges the “instance discrimination” habit of self-supervised learning. By recognizing that graphs are full of symmetries and redundancies, GALE allows models to learn richer, more semantically meaningful representations.

Key Takeaways:

- Nodes aren’t unique: Many nodes are structurally or attributively equivalent.

- Combine Structure and Features: Fusion via intersection creates the most reliable equivalence classes.

- Approximation is Key: Using PageRank and distance thresholds allows this method to scale to large, real-world graphs without NP-hard computations.

- Better than Contrastive: By expanding the definition of a “positive pair” from self-augmentation to equivalence class, GALE generalizes and outperforms standard contrastive learning.

For students and researchers in Graph Learning, GALE suggests a shift in perspective: instead of just asking “which nodes are connected?”, we should also be asking “which nodes are interchangeable?”

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/3079_equivalence_is_all_a_unif-1845/images/cover.png)