In the fast-paced world of artificial intelligence, researchers love a good mystery. Over the last few years, the community has been captivated by strange behaviors in neural networks that seem to defy the fundamental laws of statistics and learning theory. Models that get smarter after they massively overfit? Test error that goes down, then up, then down again? These phenomena—known as grokking, double descent, and the lottery ticket hypothesis—have spawned thousands of papers attempting to explain them.

But a recent position paper by Alan Jeffares and Mihaela van der Schaar from the University of Cambridge poses a provocative question: Are we wasting our time trying to “solve” these puzzles?

Their paper, Not All Explanations for Deep Learning Phenomena Are Equally Valuable, argues that the research community has fallen into a trap. By treating these phenomena as isolated riddles requiring unique solutions, we often produce “ad hoc” hypotheses that explain the specific weirdness but offer zero value to the broader field.

In this deep dive, we will explore the authors’ call for a shift toward sociotechnical pragmatism. We will examine why your favorite deep learning mysteries might not matter in the real world, and how—if we change our perspective—they could be the key to unlocking the fundamental theories of deep learning.

The Zoo of Phenomena

Before we dismantle the current research approach, we need to understand the “weird” behaviors that have captured the community’s imagination. The authors focus on three specific “edge case” phenomena that challenge our intuition.

1. Double Descent

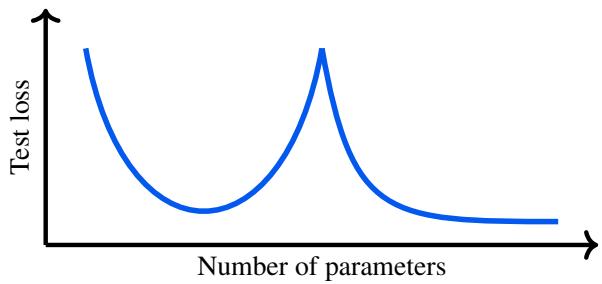

Traditional statistical wisdom (the bias-variance tradeoff) tells us that as a model becomes more complex, it eventually starts to overfit, leading to worse performance on unseen data. This usually looks like a U-shaped curve.

However, researchers observed something impossible: as you continue to add parameters beyond the point of overfitting, the test loss sometimes drops again.

As shown in Figure 1, the “Double Descent” involves a standard U-curve followed by a second drop in error. This observation was shocking because it suggested that massive over-parameterization (making the model way too big for the data) is actually good.

2. Grokking

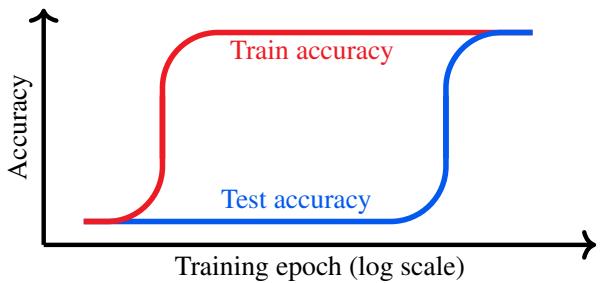

Usually, when a network achieves 100% accuracy on its training data but has low accuracy on the test set, we stop training. We call this overfitting.

“Grokking” turns this practice on its head. In specific setups, if you keep training long after the training accuracy hits 100% (and the test accuracy is flatlining), the model suddenly experiences a “phase transition.”

Figure 2 illustrates this delayed generalization. It looks like the model is memorizing the data (high train, low test) and then, magically, it “groks” the underlying rule, causing test accuracy to skyrocket.

3. The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis

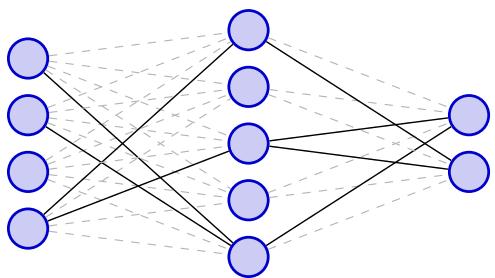

This hypothesis claims that within any massive, dense neural network, there exists a tiny sub-network (a “winning ticket”) that, if trained in isolation from the start, would reach the same performance as the full giant network.

Figure 3 visualizes this concept. The idea suggests that most of the weights in our massive models are irrelevant, and only a sparse structure is actually doing the heavy lifting.

The Reality Check: Why These Are “Edge Cases”

The authors drop a hard truth early in the paper: These phenomena rarely happen in real-world applications.

If you are training a Large Language Model (LLM) or a production computer vision system, you will likely never encounter them. Why?

- Double Descent is invisible with good practices: In the real world, we use regularization and early stopping. We don’t blindly increase parameters without tuning hyperparameters. When you apply standard techniques like optimal regularization, the double descent bump disappears. Scaling laws for models like GPT-4 or Vision Transformers generally show a smooth improvement, not a jagged double descent.

- Grokking requires synthetic setups: Grokking is typically observed on small, algorithmic datasets (like modular arithmetic). To make it happen, researchers often have to create contrived conditions, such as initializing the weights to be massive. Attempts to find “natural” grokking in realistic scenarios have mostly failed.

- Lottery Tickets are impossible to find beforehand: While the hypothesis is true—these sub-networks exist—finding them before you train the full model is currently impossible. You have to train the giant model first to find the ticket, which defeats the purpose of efficiency. As the creator of the hypothesis, Jonathan Frankle, recently admitted, it is likely not a path to practical speedups on modern hardware.

If these phenomena don’t pose practical problems for engineers building real AI systems, why are we obsessed with them?

The authors argue that we are treating them like puzzles. We see something weird, and we want to “resolve” it. But simply finding a math equation that fits the weird curve is not the same as doing science.

The Core Method: Broad Theories vs. Ad Hoc Hypotheses

This is the most critical conceptual contribution of the paper. To understand why current research is inefficient, we must distinguish between two types of explanations.

1. Narrow Ad Hoc Hypotheses

These are explanations designed specifically to fit the observed phenomenon and nothing else. They act like a “patch” to our current understanding. They might mathematically describe the curve, but they offer no predictive power for other situations and no utility for building better models.

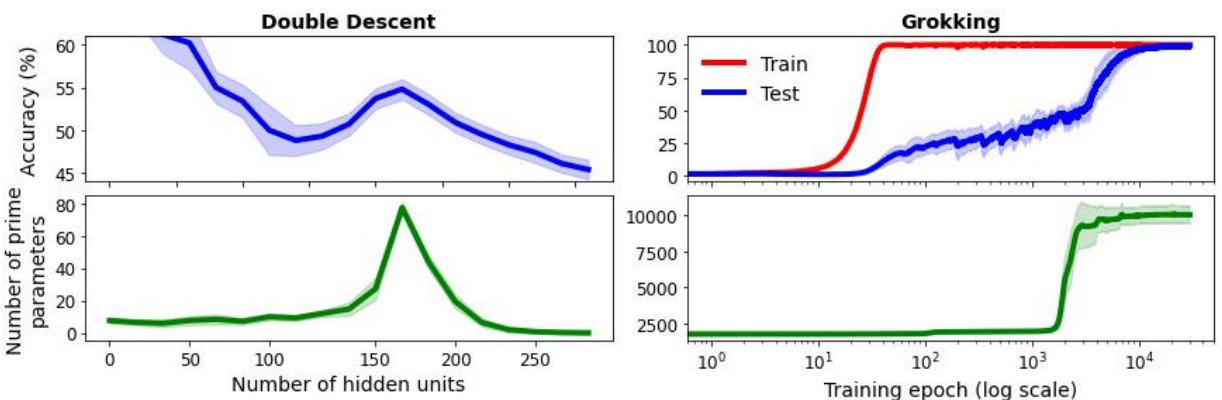

To demonstrate the absurdity of ad hoc hypotheses, the authors created a satirical “Unified Theory” of Double Descent and Grokking based on… Prime Numbers.

Look closely at Figure 4. The authors show that if you round the network parameters and count how many of them are prime numbers, the resulting curves perfectly track the test performance for both Double Descent (left) and Grokking (right).

Is the secret to deep learning hidden in prime numbers? Of course not.

This is a correlation artifact (likely due to parameter magnitude changes during training). But it illustrates the danger: you can always find a variable that correlates with a phenomenon. If you publish a paper saying “Grokking is caused by Prime Number fluctuations,” you have created a narrow ad hoc hypothesis. It is technically “true” for that specific experiment, but it is useless. It teaches us nothing about learning dynamics, optimization, or generalization.

2. Broad Explanatory Theories

In contrast, a valuable explanation is one that uses the phenomenon to refine a general principle of deep learning.

We shouldn’t ask, “How do we fix Double Descent?” (It doesn’t need fixing; it doesn’t happen in production). We should ask, “What does the existence of Double Descent tell us about the Bias-Variance Tradeoff?”

The value lies not in the puzzle itself, but in using the puzzle to stress-test our fundamental laws. The authors advocate for Sociotechnical Pragmatism: the idea that the value of knowledge is determined by its downstream utility.

Re-evaluating the Experiments: Finding the Utility

If we adopt this pragmatic view, do we toss Double Descent and Grokking in the trash? No. The authors argue they are valuable test beds, provided we stop trying to “solve” them and start using them to update our mental models.

Here is how the authors suggest we re-frame the research on these three topics:

Rethinking Double Descent

- The Wrong Approach: Trying to mathematically model the second descent peak in a vacuum.

- The Pragmatic Approach: Use it to challenge the classical Bias-Variance tradeoff. The phenomenon proved that “overfitting” isn’t a simple binary state. It led to the discovery of benign overfitting—the idea that deep models can memorize noise and still generalize well. This is a massive, generalizable insight that changes how we think about model capacity in every domain, not just the edge cases where double descent appears.

Rethinking Grokking

- The Wrong Approach: Inventing complex reasons why a model suddenly learns modular arithmetic after 10,000 epochs.

- The Pragmatic Approach: Use grokking to study progress measures. Grokking shows us that “Training Accuracy” and “Test Accuracy” are terrible metrics for understanding the internal state of a model. The model was learning during the flatline period—we just weren’t measuring the right things. This realization motivates research into “feature learning” vs. “lazy learning,” helping us develop better metrics to monitor training health in real models.

Rethinking Lottery Tickets

- The Wrong Approach: Trying to build algorithms to find tickets at initialization (which has largely failed).

- The Pragmatic Approach: Use the hypothesis to understand sparsity. Even if we can’t find tickets early, the fact that they exist proves that models are massively inefficient. This theoretical backing has supported practical advancements in quantization (making weights smaller) and parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), which are essential for running LLMs on consumer hardware today.

A Guide for Future Research

The authors conclude that we need to make research more scientific and less like a leaderboard competition. In many areas of ML, the goal is “State of the Art” (SOTA). But in studying phenomena, SOTA doesn’t apply. You aren’t trying to beat a benchmark; you are trying to uncover truth.

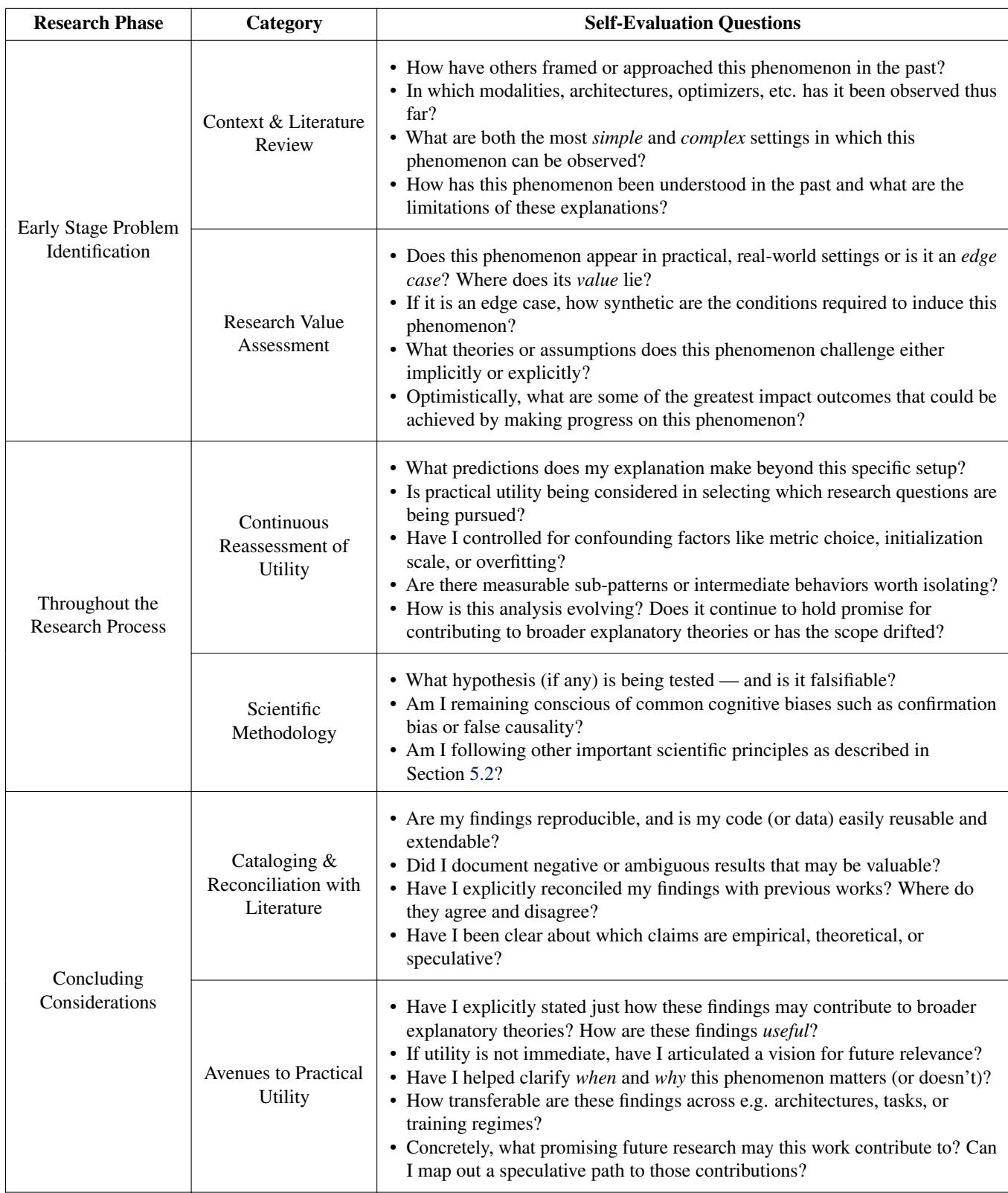

To guide researchers away from “Prime Number Theories” and toward useful science, the authors propose a self-evaluation checklist.

This checklist (Table 1) forces a researcher to pause and ask difficult questions:

- Is this an edge case? Be honest. Does this happen in ChatGPT, or only on MNIST with weird settings?

- Does my explanation predict anything else? If your theory only explains your specific graph, it’s ad hoc.

- Is it falsifiable? Can you design an experiment that would prove you wrong?

The “Scientific Method” for Deep Learning

The paper advocates for a return to classic scientific principles:

- Preregistration: State your hypothesis before running the experiment to prevent retroactively fitting a theory to the data.

- Cataloging: Instead of everyone rediscovering the same weird behaviors, the community should build high-quality, open repositories of these phenomena.

- Collaboration: Shift from competitive explanation-finding to collective theory-building.

Conclusion: From Puzzles to Progress

Deep learning is maturing. We are moving past the phase of alchemy, where we throw things into a pot and marvel at the weird smoke that comes out.

Jeffares and van der Schaar’s work is a crucial intervention. They remind us that while phenomena like Grokking and Double Descent are fascinating, they are not the end goal. We must resist the urge to act like puzzle solvers, satisfied merely when the pieces fit together.

Instead, we must act like scientists. We should view these anomalies as stress tests—opportunities to break our current theories and build more robust, generalizable laws that actually help us deploy reliable AI in the real world.

The next time you see a paper claiming to “solve” a deep learning mystery, ask yourself: Is this a broad explanatory theory, or is it just counting prime numbers?

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/347_position_not_all_explanati-1793/images/cover.png)