The capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) have exploded in recent years, largely due to their ability to process massive amounts of text. But as we move from text to video, we hit a new wall. Video isn’t just “text with pictures”—it is a complex, three-dimensional medium combining spatial details (what is happening in the frame) with temporal progression (when it is happening).

Most current Video LLMs try to adapt text-based techniques directly to video, often with mixed results. The most critical component in this adaptation is Position Embedding—the way the model knows where a piece of information is located.

In this post, we are diving deep into VideoRoPE, a research paper that fundamentally rethinks how we encode position in video data. We will explore why current methods fail when videos get long or repetitive, and how a new 3D architectural approach solves these problems to achieve state-of-the-art results in video understanding and retrieval.

The Challenge: From Text to Video

To understand VideoRoPE, we first need to understand the mechanism it improves upon: Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE).

In the world of Transformers (the architecture behind GPT, LLaMA, and Qwen), the model processes tokens in parallel. Without position embeddings, the model would have no idea if the word “dog” came before or after the word “bites.” RoPE solves this by rotating the embedding of a token in a geometric space. The angle of rotation corresponds to the token’s position.

The Limitations of Vanilla RoPE

The original RoPE (Vanilla RoPE) was designed for 1D sequences—lines of text. When researchers started building Video LLMs, they faced a choice:

- Flatten the Video: Treat the video frames as one long line of 1D tokens. This destroys the spatial relationship between pixels (vertical and horizontal neighbors).

- 3D RoPE: Try to encode Time (\(t\)), Height (\(y\)), and Width (\(x\)) separately.

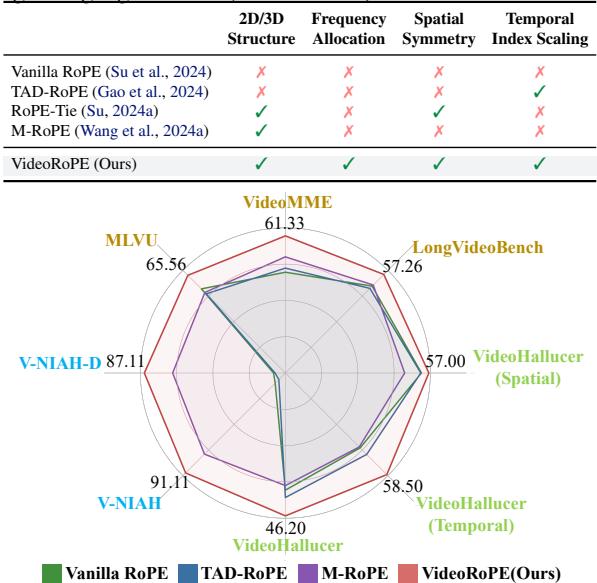

While 3D approaches like M-RoPE (used in Qwen2-VL) are a step in the right direction, they suffer from subtle but critical mathematical flaws. As shown in the comparison below, existing methods fail to satisfy all the necessary characteristics for robust video modeling: 3D structure, correct frequency allocation, spatial symmetry, and index scaling.

The authors of VideoRoPE identified that simply splitting dimensions isn’t enough. You have to decide which dimensions represent time and which represent space. Make the wrong choice, and your model becomes “confused” by repetitive visual data.

The Litmus Test: The “Distractor” Problem

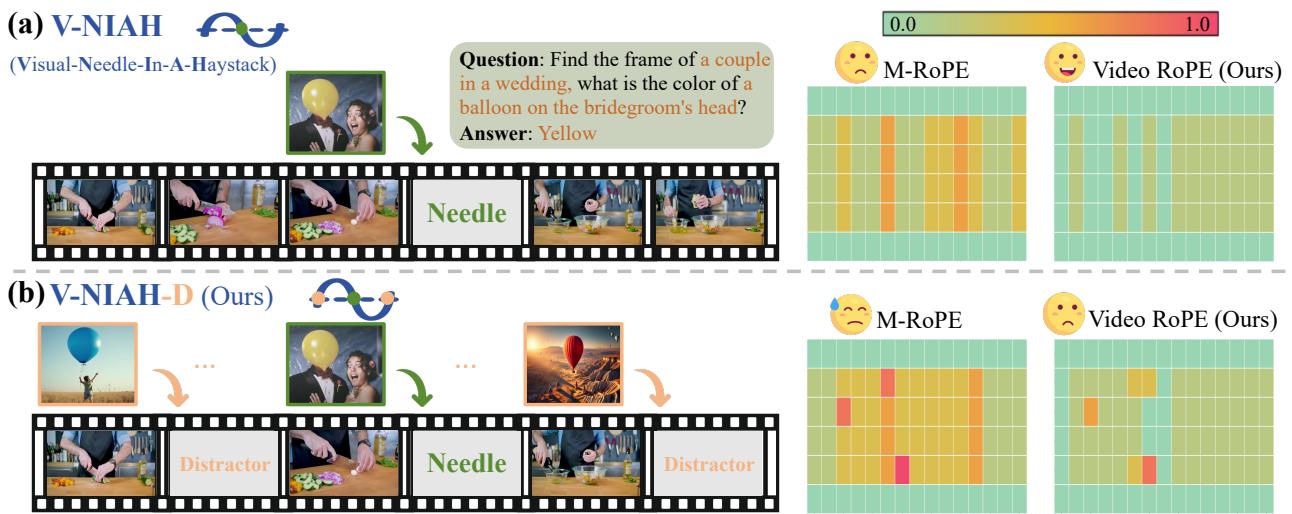

To prove that existing methods were flawed, the researchers introduced a new, harder benchmark: V-NIAH-D (Visual Needle-In-A-Haystack with Distractors).

The standard “Needle In A Haystack” test hides a specific image (the needle) inside a long video (the haystack) and asks the model to find it. Most models are decent at this. However, the researchers added a twist: Distractors. They inserted images that looked semantically similar to the needle but weren’t the correct target.

As you can see in the figure above, previous methods like M-RoPE (the second row in the heatmap) perform reasonably well on the standard task (a). But the moment distractors are introduced (b), their performance collapses (more red/orange areas).

Why? Because the model’s position embedding for “Time” was periodic. It was confusing the “needle” at frame 100 with a “distractor” at frame 1000 because, mathematically, their position encodings looked too similar. This phenomenon is known as a hash collision in position space.

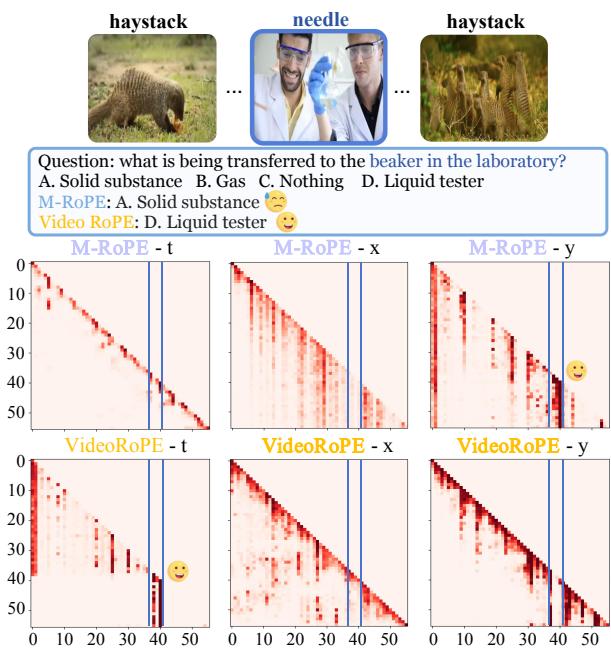

Analyzing the Failure: Why Frequency Matters

To understand why these collisions happen, we have to look at the math of RoPE. RoPE rotates vectors at different frequencies.

\[ A _ { t _ { 1 } , t _ { 2 } } = ( q _ { t _ { 1 } } R _ { t _ { 1 } } ) \left( k _ { t _ { 2 } } R _ { t _ { 2 } } \right) ^ { \top } = q _ { t _ { 1 } } R _ { \Delta t } \pmb { k } _ { t _ { 2 } } ^ { \top } , \]In a standard feature vector (of size \(d=128\), for example), the dimensions are not all equal.

- Lower dimensions (indices \(0, 1, 2...\)) are rotated at high frequencies. They spin very fast.

- Higher dimensions (indices \(...126, 127\)) are rotated at low frequencies. They spin very slowly.

The Problem with Previous Methods (M-RoPE): M-RoPE assigned the Temporal (Time) information to the lower dimensions (the first 16-32 dimensions). These dimensions rotate rapidly. This means the positional signal repeats itself quickly (oscillation). If you have a long video, the position embedding for “Minute 1” might look mathematically identical to “Minute 5.”

The visualization below illustrates this failure clearly. The top row (M-RoPE) focuses its attention on spatial features (\(x, y\)) rather than time (\(t\)), failing to lock onto the correct frame when distractors are present.

Notice the bottom row (VideoRoPE). By fixing the frequency allocation (which we will detail next), the model can distinctly attend to the temporal dimension (VideoRoPE-t), ignoring the distractors.

The Core Method: VideoRoPE

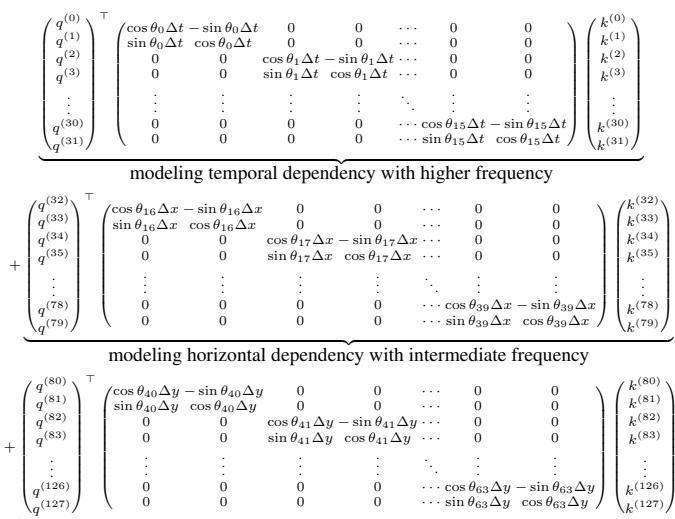

VideoRoPE introduces a 3D position embedding strategy built on three pillars designed to solve the issues of oscillation, symmetry, and scaling.

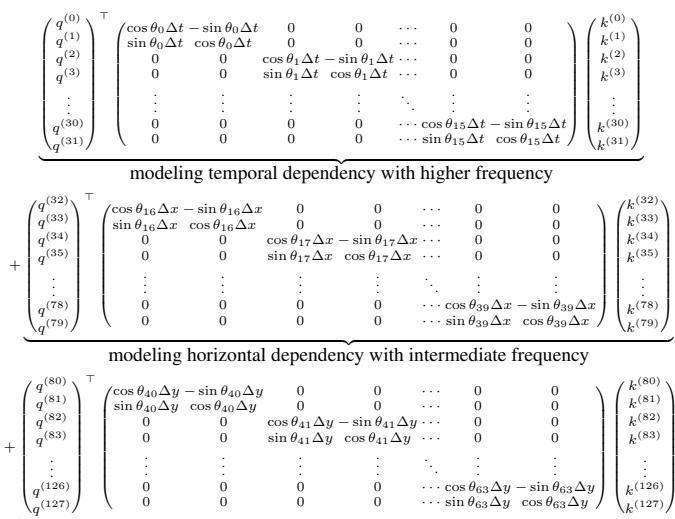

1. Low-Frequency Temporal Allocation (LTA)

The most significant contribution of VideoRoPE is flipping the script on frequency. Instead of using the high-frequency (low index) dimensions for Time, VideoRoPE assigns Time to the highest dimensions (low frequency).

Why does this matter?

- High Frequency (Lower Dimensions): Great for local details, but the wave repeats quickly.

- Low Frequency (Higher Dimensions): The wave has a very long period. It effectively never repeats within the context of a standard video.

By moving the temporal component \(t\) to the end of the feature vector, VideoRoPE ensures that the position embedding changes monotonically over time. Frame 1000 looks distinctly different from Frame 100.

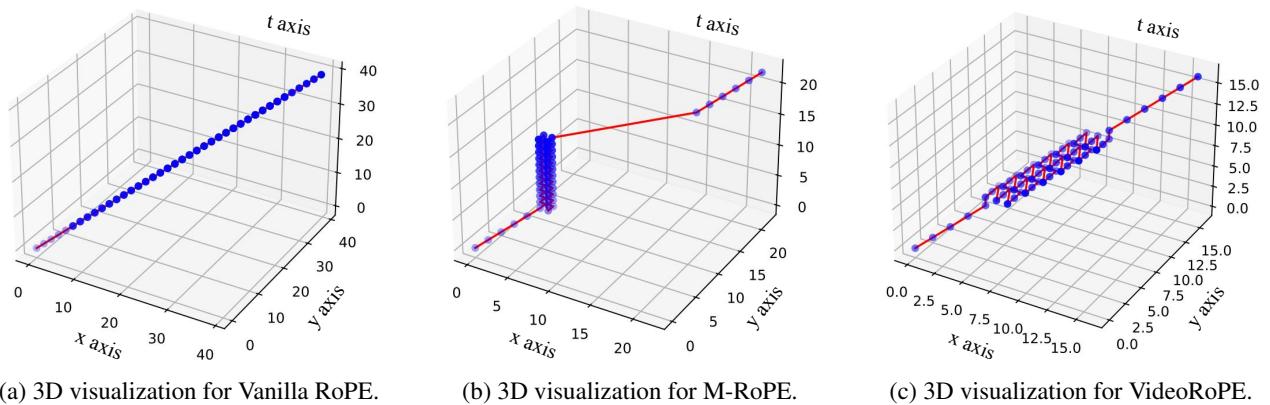

Let’s look at a 3D visualization of the frequency waves:

Above: (a) M-RoPE uses high-frequency dimensions for time. Notice the “ripples”—these are oscillations. Points at different times get the same value (Hash Collision).

Above: (a) M-RoPE uses high-frequency dimensions for time. Notice the “ripples”—these are oscillations. Points at different times get the same value (Hash Collision).

Above: (b) VideoRoPE uses low-frequency dimensions. The surface is smooth and flat. Every point in time has a unique value.

Above: (b) VideoRoPE uses low-frequency dimensions. The surface is smooth and flat. Every point in time has a unique value.

This simple change eliminates the “hash collisions” that made previous models vulnerable to distractors.

2. Diagonal Layout (DL) for Spatial Symmetry

The second innovation addresses how we organize the spatial dimensions (\(x\) and \(y\)) relative to time.

In previous approaches like M-RoPE, the indexing for visual tokens was somewhat disjointed from text tokens. Specifically, M-RoPE would stack indices in a way that clustered them in the corners of the coordinate system. This created a lack of Spatial Symmetry—the visual tokens didn’t flow naturally from the text tokens preceding them.

VideoRoPE proposes a Diagonal Layout. Instead of resetting indices or stacking them, it arranges the entire input along the diagonal of the 3D space.

- (a) Vanilla RoPE: A straight line (1D). No spatial width.

- (b) M-RoPE: Notice the vertical “walls.” The indices stop growing in certain directions, creating unnatural clusters.

- (c) VideoRoPE: The indices (red and blue dots) follow a dense, diagonal path.

This layout ensures that the relative position between any two visual tokens is preserved, and importantly, the “distance” between the end of the text prompt and the start of the video is consistent. It mimics the natural linear growth of text tokens while retaining 3D spatial information.

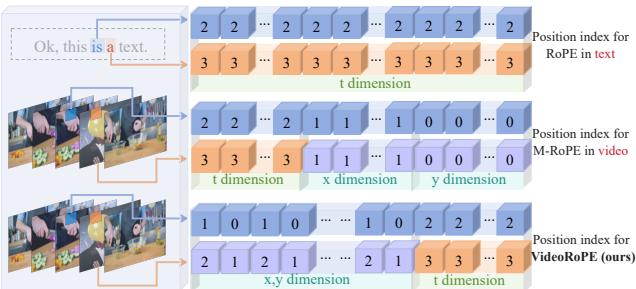

This is further visualized by looking at how the tokens are interleaved:

In the bottom row (VideoRoPE), notice how the spatial (\(x,y\)) and temporal (\(t\)) designs are interleaved to maintain a structure that feels “native” to the Transformer, which was originally trained on 1D text.

3. Adjustable Temporal Spacing (ATS)

Finally, there is the issue of granularity. A single step in a text sequence (one word) is not semantically equivalent to a single step in a video (one frame). Videos often have high redundancy; two adjacent frames are nearly identical, whereas two adjacent words are usually different.

VideoRoPE introduces a scaling factor, \(\delta\), to decouple the video frame index from the raw token index.

\[ \begin{array}{c} \begin{array} { r } { ( t , x , y ) = \left\{ \begin{array} { l l } { ( \tau , \tau , \tau ) } & { \mathrm { i f ~ } 0 \leq \tau < T _ { s } } \\ { } \\ { } \\ { \left( T _ { s } + \delta ( \tau - T _ { s } ) , \right)} \\ { T _ { s } + \delta ( \tau - T _ { s } ) + w - \frac { W } { 2 } , } \\ { T _ { s } + \delta ( \tau - T _ { s } ) + h - \frac { H } { 2 } } \end{array} \right.} & { \mathrm { i f ~ } T _ { s } \leq \tau < T _ { s } + T _ { v } } \\ { } \\ { \left( \begin{array} { l } { \tau + ( \delta - 1 ) T _ { v } , } \\ { \tau + ( \delta - 1 ) T _ { v } , } \\ { \tau + ( \delta - 1 ) T _ { v } } \end{array} \right) } & { \mathrm { i f ~ } T _ { s } + T _ { v } \leq \tau < T _ { s } + T _ { v } + T _ { c } } \end{array} \end{array} \]This equation might look intimidating, but the concept is simple:

- Start Text: Use standard indices.

- Video: Multiply the frame index relative to the start ($ \tau - T_s \() by $\delta\). This allows the model to “stretch” or “compress” time perception.

- End Text: Resume linear indexing from where the video left off.

This decoupling allows VideoRoPE to handle videos of varying frame rates and lengths without confusing the model’s internal clock.

Experiments and Results

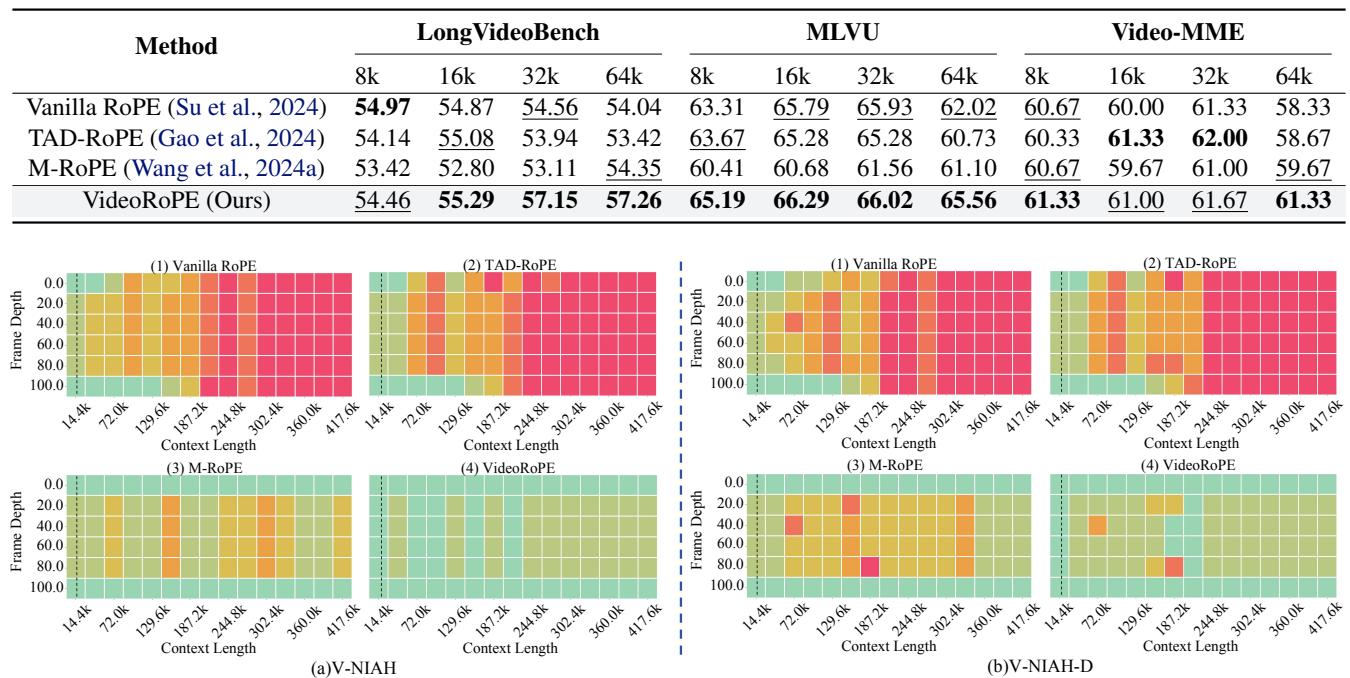

Does this theoretical restructuring actually work? The authors put VideoRoPE to the test against Vanilla RoPE, TAD-RoPE, and M-RoPE across several benchmarks.

Long Video Retrieval (V-NIAH & V-NIAH-D)

The most dramatic results come from the retrieval tasks. The heatmaps below show accuracy (Green = 100%, Red = 0%) across different context lengths (X-axis) and frame depths (Y-axis).

Look at section (b) V-NIAH-D (the bottom row of charts):

- Vanilla RoPE (1) & TAD-RoPE (2): Almost completely red. They fail to find the needle when distractors are present.

- M-RoPE (3): Better, but still has significant red patches, indicating instability.

- VideoRoPE (4): almost entirely green. It is robust to distractors and functions effectively even at extreme context lengths.

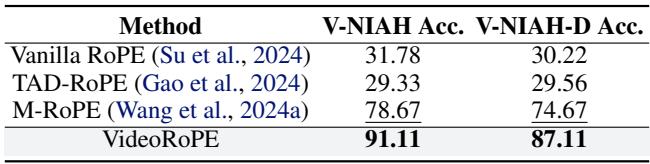

The quantitative data backs this up:

VideoRoPE achieves 87.11% accuracy on the difficult V-NIAH-D task, compared to just 74.67% for M-RoPE and ~30% for Vanilla/TAD-RoPE.

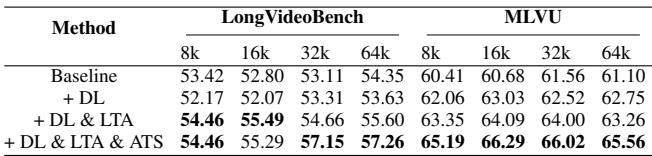

Long Video Understanding

Beyond just finding images, the model needs to understand what is happening. The authors tested on benchmarks like LongVideoBench and MLVU (Multi-Task Long Video Understanding).

(Note: Refer to the table section of this image)

(Note: Refer to the table section of this image)

VideoRoPE consistently scores higher (marked in bold) across different context lengths (8k to 64k). It shows particular strength in maintaining performance as the context length increases, whereas other methods tend to degrade.

Ablation Studies: Do we need all components?

A crucial part of any research paper is the Ablation Study—removing parts of the system to see if they are actually necessary.

The results show a clear stair-step improvement:

- Baseline (M-RoPE): 54.35 score.

- + Diagonal Layout (DL): Performance drops slightly on some metrics but improves stability.

- + DL & LTA (Low-frequency Temporal Allocation): Big jump to 55.60. The frequency fix is the biggest contributor.

- + DL & LTA & ATS (Full VideoRoPE): Final jump to 57.26.

This confirms that the combination of symmetry (DL), proper frequency usage (LTA), and scaling (ATS) is required for optimal performance.

Conclusion

VideoRoPE represents a significant step forward in how we adapt Large Language Models for video. The paper highlights a subtle but profound lesson: math matters. Simply plugging a 3D input into a 1D or poorly optimized 3D embedding scheme introduces invisible errors—oscillations and collisions—that confuse the model when complexity increases.

By adhering to four key principles—3D structure, Low-Frequency Temporal Allocation, Spatial Symmetry, and Adjustable Temporal Spacing—VideoRoPE provides a robust foundation for the next generation of Video LLMs. It allows models to “see” time clearly, distinguishing between the needle and the distractor, no matter how long the video gets.

As we move toward AI agents that can watch movies, analyze security footage, or understand hours of real-time interaction, robust positional embeddings like VideoRoPE will be the silent engine making it all possible.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/3607_videorope_what_makes_for_-1874/images/cover.png)