Protein design has long been described as the “inverse protein folding problem.” If folding is nature’s way of turning a sequence of amino acids into a 3D structure, design is our attempt to find a sequence that will fold into a specific, desired shape.

For years, this field has been dominated by a divide-and-conquer strategy. Researchers typically generate a backbone structure first (the ribbon), and then use a separate model to “paint” the sequence and side-chains onto that backbone. While effective, this approach ignores a fundamental biological reality: a protein’s backbone and its side-chains are intimately linked. The specific chemistry of the atoms determines the fold, and the fold determines which atoms fit.

Enter Pallatom, a new generative model that attempts to bridge this gap. By modeling the joint distribution of the structure and sequence simultaneously—specifically by focusing on the probability of all atoms (\(P(all\text{-}atom)\))—Pallatom achieves state-of-the-art results in generating high-fidelity, diverse, and novel proteins.

In this post, we will deconstruct the Pallatom paper. We will explore the ingenious “atom14” representation that solves the variable-atom problem, the dual-track architecture that powers the model, and the experimental results that suggest we are entering a new era of co-generative protein design.

The Core Problem: The Sequence-Structure Disconnect

To understand why Pallatom is significant, we need to look at the current landscape of protein modeling. Historically, the field has relied on two conditional probabilities:

- \(P(structure \mid seq)\): Predicting structure from a known sequence (e.g., AlphaFold).

- \(P(seq \mid backbone)\): Designing a sequence for a fixed backbone (e.g., ProteinMPNN).

Most generative pipelines chain these together. They might hallucinate a backbone structure first and then optimize a sequence for it. Mathematically, this approximates the joint probability as \(P(backbone) \cdot P(seq \mid backbone)\).

The limitation? This step-wise process decouples the backbone from the side-chains. It assumes you can design a perfect backbone without knowing what amino acids will populate it. However, in nature, bulky side-chains, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions often dictate the backbone’s twist and turn. By ignoring these all-atom interactions during the initial generation, we limit the design space and accuracy.

Pallatom aims to model the joint distribution \(P(structure, seq)\) directly. It treats the protein as a cloud of atoms where the geometry itself encodes the sequence information.

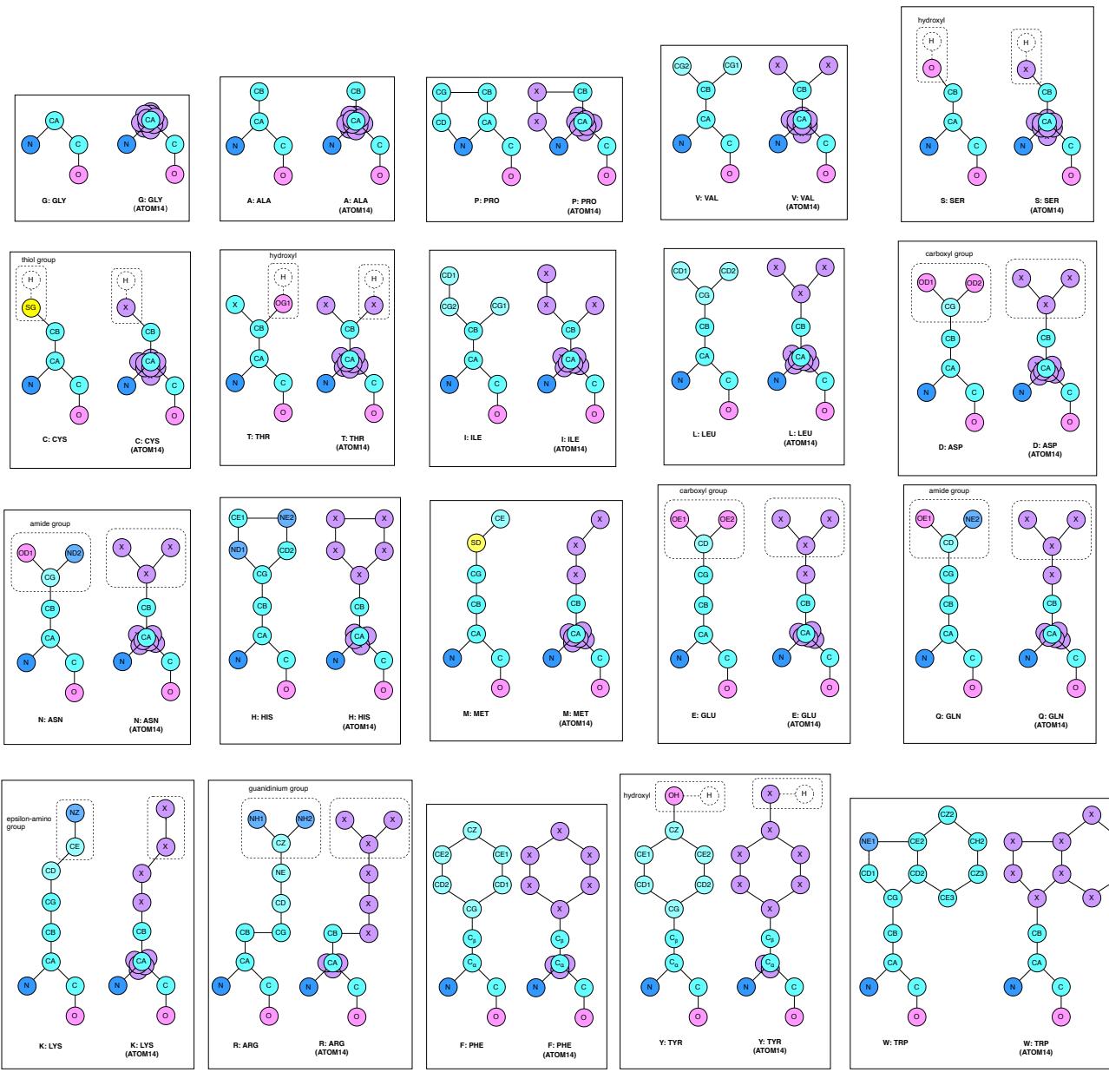

The “atom14” Representation: Solving the Variable Atom Dilemma

The first hurdle in all-atom generation is representation. In a diffusion model, we typically transform noise into data. But if we don’t know the amino acid sequence yet, we don’t know how many atoms are in each residue. A Glycine residue has only 4 heavy atoms; a Tryptophan has 14. How do you construct a neural network for a system where the number of particles is unknown and changing?

Pallatom introduces atom14, a unified representation framework.

As shown in Figure 3, atom14 standardizes every residue to a fixed size of 14 atoms. Here is the clever part:

- Standardization: Every position in the protein is assigned slots for up to 14 atoms.

- Virtual Atoms: For smaller amino acids, the “excess” atom slots are not left empty (which would require knowing the type) but are collapsed onto the coordinate of the Alpha Carbon (\(C_\alpha\)).

- No Leaking: At the start of generation, the model doesn’t need to know the specific element of a side-chain atom. It treats them as generic “masked” particles in a point cloud.

This allows the model to hallucinate a “superposition” of possible side-chains. As the structure refines during diffusion, the geometry of these 14 points begins to resemble a specific amino acid. This eliminates the conflict between designing sequence and structure—they emerge together from the noise.

The Pallatom Architecture

Pallatom employs a diffusion-based framework. Specifically, it uses EDM (Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion-Based Generative Models), a robust formulation for generating coordinate data.

The Diffusion Process

The goal is to reverse a process that gradually adds noise to a protein structure until it is a random cloud of points. The generative process (denoising) is defined by a differential equation:

The model learns a function \(D_\theta\) that predicts the clean, denoised coordinates from a noisy input. This is trained using a weighted mean squared error loss:

In practice, the network predicts the final clean structure at every step, and the diffusion scheduler interpolates between this prediction and the current noisy state to take a small step forward.

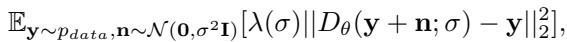

The MainTrunk and AtomDecoder

The neural network driving this process is sophisticated. It needs to process information at two levels simultaneously: the residue level (the sequence of amino acids) and the atomic level (the 3D point cloud).

Figure 1 illustrates the architecture, which consists of two main components:

- MainTrunk (Figure 1A): This is the encoder. It takes the noisy coordinates and “self-conditioning” information (guesses from the previous step) and initializes the features. It sets up a Dual-Track Representation:

- Residue Track: Handles features like relative positions and pair interactions between amino acids (\(z_{ij}\) and \(s_i\)).

- Atom Track: Handles the explicit 3D coordinates of the 14 atoms per residue.

- AtomDecoder (Figure 1B): This is the engine of the model. It contains multiple decoding units that iteratively refine the structure.

- Information Flow: It uses a “traversing” representation. Information flows from the residue level down to the atoms (broadcasting) and from the atoms back up to the residues.

- Triangle Updates: Borrowing from AlphaFold, it uses triangle attention mechanisms to ensure the pairwise distances between residues are geometrically consistent.

- Recycling: Crucially, the outputs of one block are not just passed to the next; the predicted geometry is “recycled” back into the pair representations (\(z_{ij}\)), allowing the model to refine its understanding of the global topology over time.

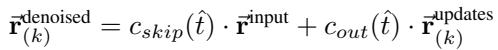

The update rule for the coordinates at step \(k\) combines the input with the network’s predicted update, scaled by noise factors:

From Geometry to Sequence

Pallatom generates a 3D structure, but we ultimately need a sequence of letters (amino acids). Because the atom14 representation encodes the side-chain geometry so precisely, the sequence is actually implicit in the structure.

If the model generates a perfect two-ring side-chain shape, it must be Tryptophan. If it generates a short, branched chain, it’s Valine or Threonine.

Pallatom uses a module called SeqHead. It takes the final geometric embeddings of the atoms, aggregates them, and passes them through a simple linear layer to predict the probability of each of the 20 amino acids. This is a “structure-to-sequence” decoding that happens naturally at the end of the generation.

Training Objectives

To train Pallatom, the researchers use a composite loss function that enforces both local chemical validity and global structural coherence.

The total loss \(\mathcal{L}\) includes:

- \(\mathcal{L}_{atom}\): The standard diffusion loss (MSE) on the atom coordinates.

- \(\mathcal{L}_{seq}\): Cross-entropy loss to ensure the predicted sequence matches the ground truth.

- \(\mathcal{L}_{smooth\_lddt}\): A loss based on the Local Distance Difference Test (LDDT). This optimizes the model to get the local geometry right (like bond lengths and side-chain packing), which is critical for physical realism.

- \(\mathcal{L}_{dist}\): Distogram losses that supervise the pairwise distances between residues and atoms, helping the model learn global topology.

Experimental Results

Does learning \(P(all\text{-}atom)\) actually work better than splitting the task? The results suggest a resounding yes.

Designability and Diversity

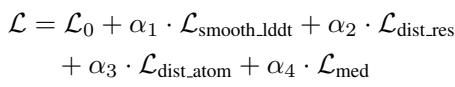

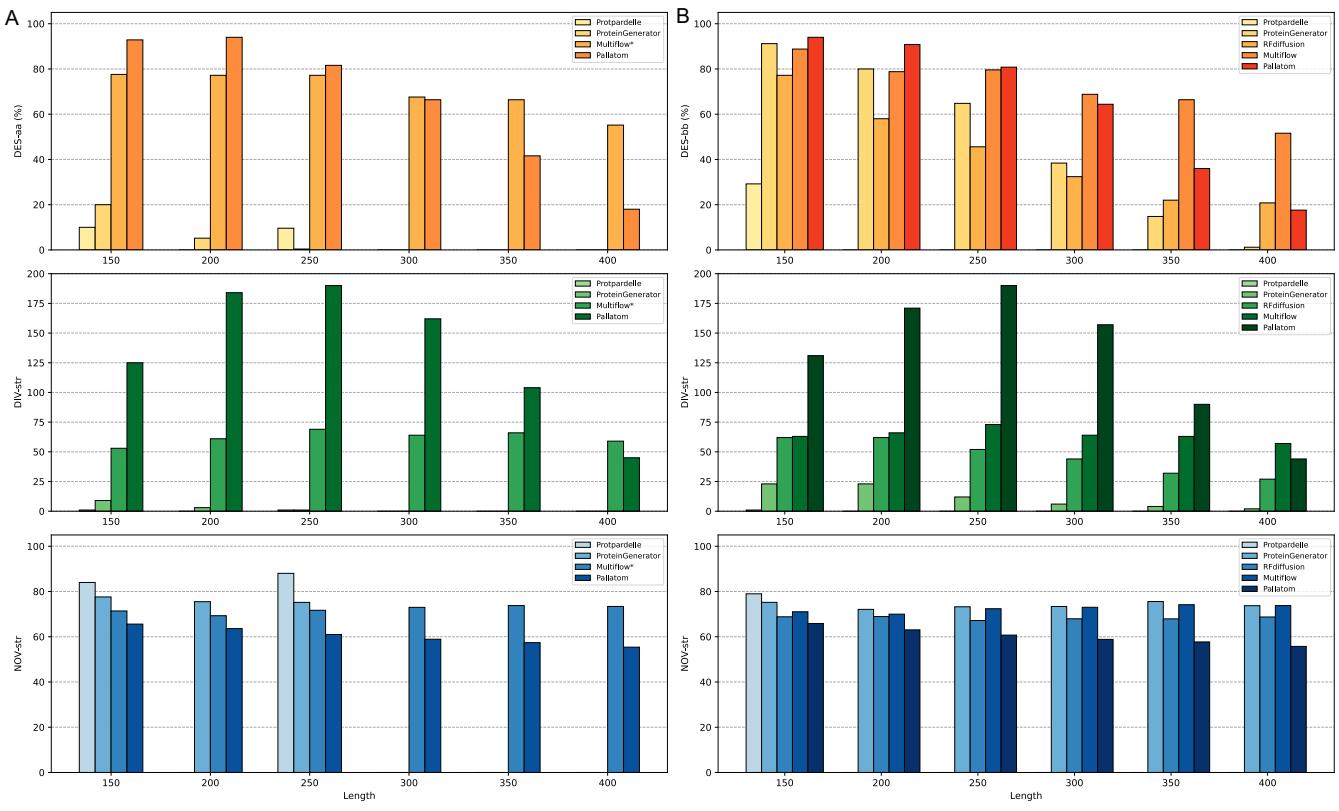

The researchers benchmarked Pallatom against other state-of-the-art models, including Protpardelle (another all-atom model), ProteinGenerator, Multiflow, and RFDiffusion (backbone only).

The key metric is DES-aa (All-Atom Designability): If we take the generated sequence and fold it using ESMFold, does it match the generated structure?

Table 1 highlights the performance gap. Pallatom achieves a massive 85.03% in DES-aa, significantly outperforming Protpardelle (30%) and Multiflow (62.74%).

Even more impressive is the Diversity (DIV-str). Often, generative models suffer from “mode collapse,” producing the same few safe structures repeatedly. Pallatom generated 291 unique structural clusters, nearly double the diversity of RFDiffusion (165) and far exceeding ProteinGenerator (83).

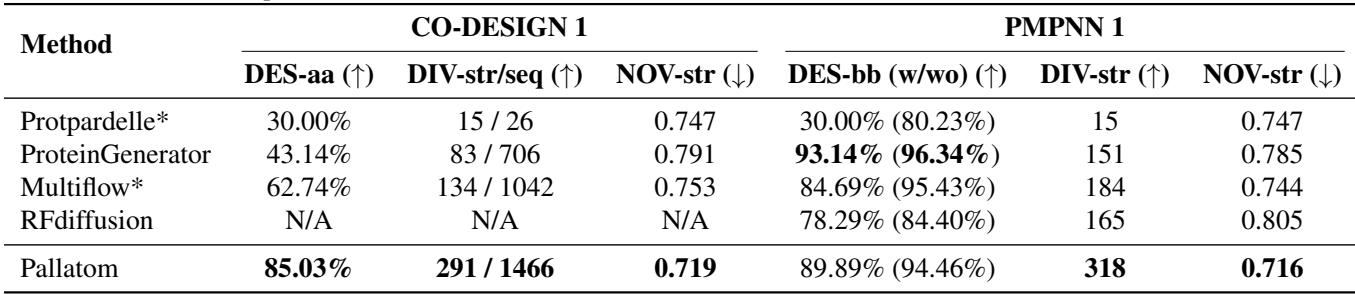

Figure 2 provides a visual confirmation. Panel A shows that the RMSD (error) between the generated and folded structures is consistently low. Panel D showcases the generated proteins: they are compact, well-folded, and exhibit distinct secondary structures.

Scaling to Larger Proteins

One of the hardest tests for a generative model is Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) generalization. Can a model trained on smaller proteins generate large, complex ones?

The researchers tested Pallatom on proteins up to 400 residues long (significantly longer than the training crop size).

As seen in Figure 4, Pallatom (purple bars) maintains high designability even at length 300+, where other methods begin to fail. It is the only method that remains robust in generating all-atom structures at length 400.

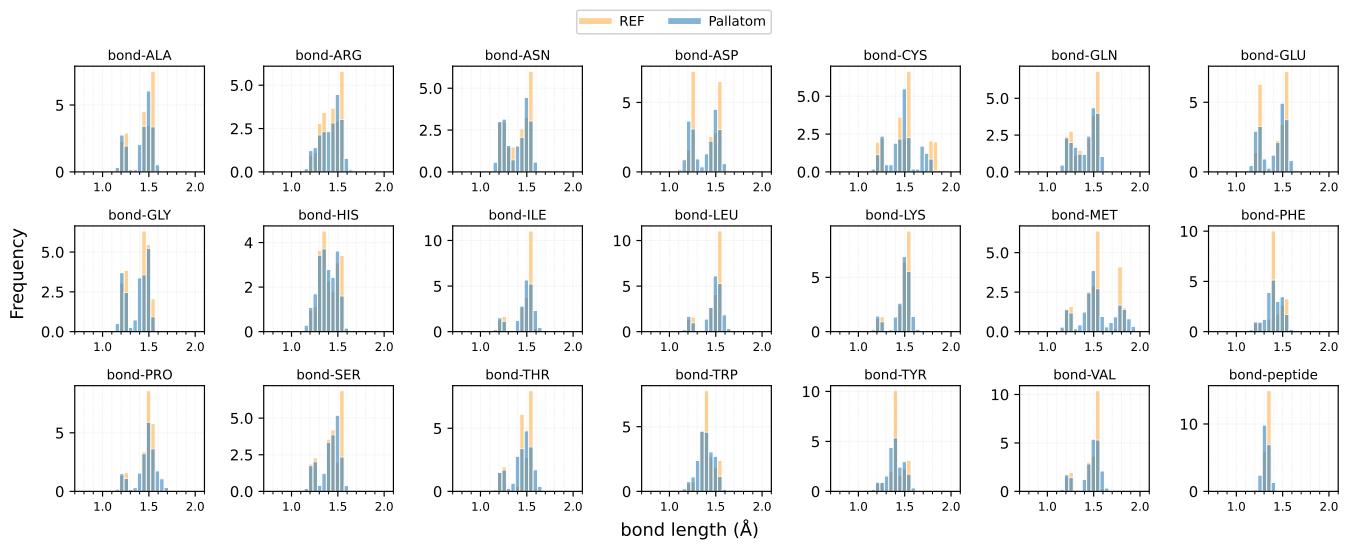

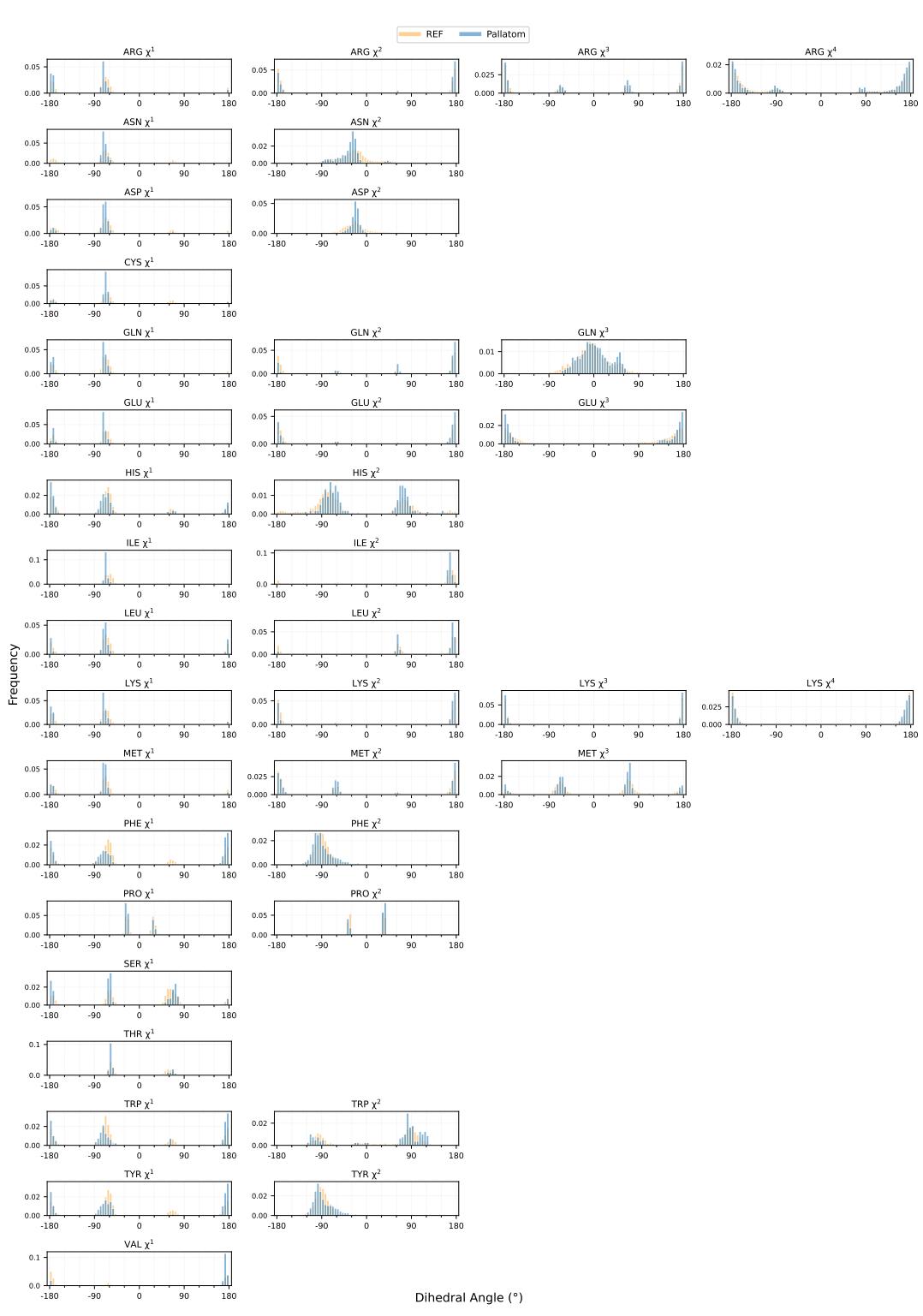

Physical Realism

A common failure mode in protein design is “hallucinating” structures that look good as ribbons but are chemically impossible (e.g., overlapping atoms or stretched bonds).

Pallatom’s focus on all-atom coordinates pays off here. The researchers compared the distribution of bond lengths and angles in generated proteins vs. natural proteins (PDB).

Figure 6 shows the bond length distributions. The generated proteins (blue) align almost perfectly with the natural reference (orange).

Similarly, Figure 8 shows the \(\chi\)-angles (side-chain torsion angles). These angles determine how side-chains pack into the protein core. Pallatom accurately reproduces the rotameric states found in nature, proving it has learned the underlying physics of atomic packing.

Conclusion

Pallatom represents a significant step forward in computational biology. By abandoning the sequential “backbone-then-sequence” paradigm and embracing a unified \(P(all\text{-}atom)\) approach, it resolves the dependencies between geometry and chemistry that define protein folding.

The introduction of the atom14 representation and the Dual-Track architecture allows the model to “dream” in full atomic detail. The result is a generator that is not only more accurate but also more diverse and scalable than its predecessors.

As we move toward designing complex enzymes, binders, and molecular machines, models like Pallatom that understand the intricate dance of every single atom will be essential tools in the protein engineer’s kit.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/4192_p_all_atom_is_unlocking_n-1776/images/cover.png)