Simulating the atomic world is one of the holy grails of computational science. From discovering new battery materials to designing novel drugs, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations allow us to peek into the movement of atoms over time. Historically, scientists have had to choose between two extremes: Quantum Mechanical methods (highly accurate but painfully slow) or classical force fields (fast but often inaccurate).

In recent years, a third contender has emerged: Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs). Specifically, Equivariant MLIPs have revolutionized the field by achieving quantum-level accuracy with significantly better efficiency. They respect the physical laws of symmetry—if you rotate a molecule, the forces acting on it should rotate with it.

However, “better efficiency” is relative. These models are still computationally heavy. Training them can take days, and inference speeds often limit the size of the molecular systems we can simulate. The culprit? A specific mathematical operation known as the Tensor-Product layer.

In this post, we will dive deep into FlashTP, a new library presented at ICML 2025 by researchers from Seoul National University. FlashTP systematically dismantles the inefficiencies of the Tensor-Product layer, achieving massive speedups (up to 40x on specific kernels) and enabling simulations of thousands of atoms that were previously impossible due to memory constraints.

Background: The Architecture of Atomic Intelligence

To understand how FlashTP works, we first need to understand what it is accelerating.

The MLIP Pipeline

At a high level, an MLIP model functions as a function approximator for potential energy surfaces. Given a set of atomic positions and their atomic numbers (types), the model predicts the total potential energy of the system.

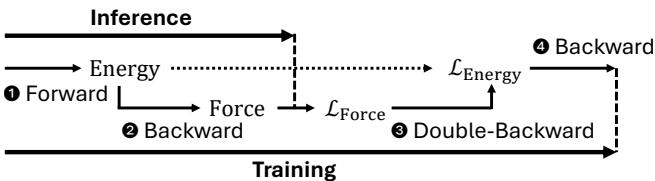

As shown in Figure 1, the process involves two distinct phases:

- Forward (Energy Prediction): The model takes the atomic graph and outputs an energy scalar.

- Backward (Force Calculation): Because Force is the negative gradient of Energy (\(F = -\nabla E\)), we calculate forces by taking the gradient of the predicted energy with respect to atomic positions.

During training, this gets even more complex. To update the model weights, we need to calculate the loss on both Energy and Forces. Since Forces are already a gradient derivative, training against Force loss requires a “double-backward” pass (the gradient of the gradient). This makes the backward and double-backward passes computationally critical.

The Structure of Equivariant Models

State-of-the-art models like NequIP, MACE, and SevenNet are built on Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). In these graphs, atoms are nodes, and interactions between neighbors are edges.

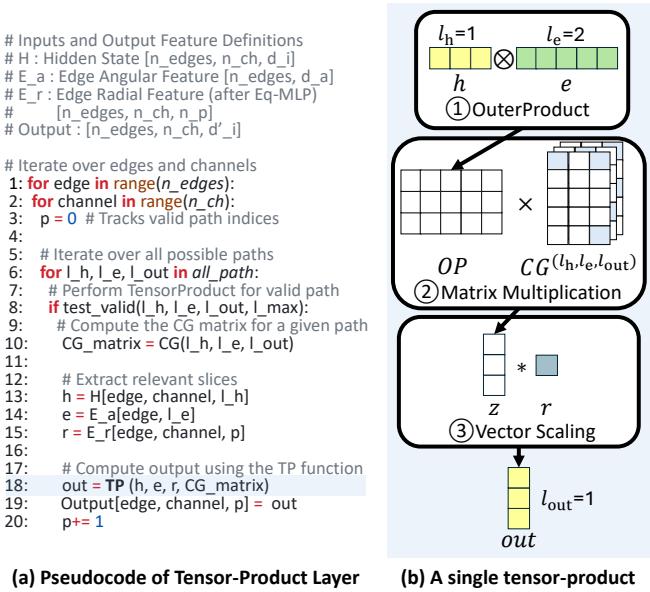

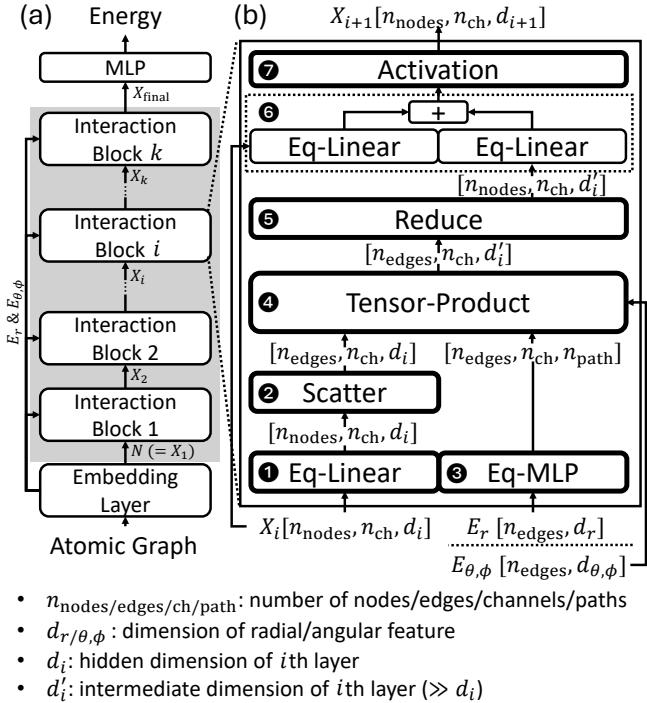

Figure 2 illustrates the typical architecture. The model is composed of a stack of “Interaction Blocks.” Inside each block, information is exchanged between atoms to update their internal representations (hidden states). This message-passing mechanism allows an atom to “learn” about its local environment.

The heart of this message passing is the Tensor-Product Layer (labeled step 4 in Figure 2b). This layer combines features from a node (the atom) with features from the edge (angular and radial information about the neighbor) to produce a new representation.

The Mathematical Bottleneck: Tensor Products

Why is this specific layer so expensive? It comes down to the complexity of maintaining equivariance. To ensure the physics holds up under rotation, we can’t just multiply vectors. We must combine “geometric tensors” using specific rules.

Figure 3 breaks down the operation. A single Tensor-Product layer involves performing many individual tensor-product operations for every edge in the graph, across multiple channels and “paths.”

A path is defined by the combination of the input degrees (\(l_h\) for hidden node features, \(l_e\) for edge features) and the desired output degree (\(l_{out}\)). The computation involves:

- Outer Product: Creating a massive temporary matrix from the input vectors.

- Clebsch-Gordan (CG) Multiplication: Multiplying that matrix by CG coefficients—constant values derived from quantum mechanics that enforce rotational symmetry.

- Scaling: Applying a learnable weight.

This operation is mathematically elegant but computationally brutal. As the degree of features (\(l_{max}\)) increases to capture finer physical details, the number of paths and the size of computations grow exponentially.

Identifying the Inefficiencies

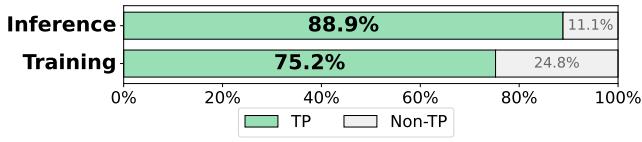

The authors of the FlashTP paper analyzed the performance of SevenNet-13i5, a state-of-the-art model, and found that the Tensor-Product layer is the undisputed bottleneck.

As Figure 4 shows, this single layer consumes nearly 89% of inference time and 75% of training time. If you want to speed up MLIPs, you must fix the Tensor Product.

The researchers identified three primary sources of inefficiency:

- Memory Traffic (The Bandwidth Wall): The operation generates massive intermediate tensors (the results of outer products) that are written to GPU memory only to be read back immediately for the next step.

- Memory Spikes (The Capacity Wall): The output of the Tensor-Product layer is often an order of magnitude larger than the input. Even if the subsequent layer (Reduce) compresses it, the GPU must allocate enough memory to hold the full uncompressed output, causing Out-Of-Memory (OOM) errors on large graphs.

- Ineffectual Computation (The Sparsity Problem): The Clebsch-Gordan matrices used to enforce symmetry are incredibly sparse. Most values are zero. Standard matrix multiplication wastes time multiplying zeros.

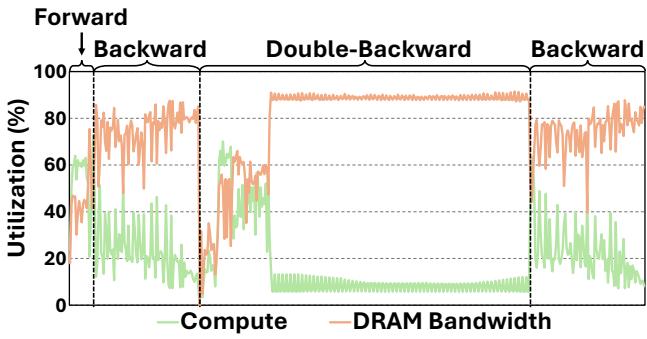

Let’s look at the resource utilization to confirm this:

Figure 6 reveals a telling story. During the Backward and Double-Backward passes (crucial for training and force calculation), the GPU is memory bound (orange line is high), while compute utilization (green line) drops. The GPU is starving for data, waiting on slow memory access rather than crunching numbers.

The FlashTP Solution

FlashTP addresses these bottlenecks with three distinct optimization strategies: Kernel Fusion, Sparsity-Aware Computation, and Path-Aggregation.

1. Kernel Fusion

The first step to solving the memory bandwidth issue is to stop writing intermediate data to the main GPU memory (DRAM).

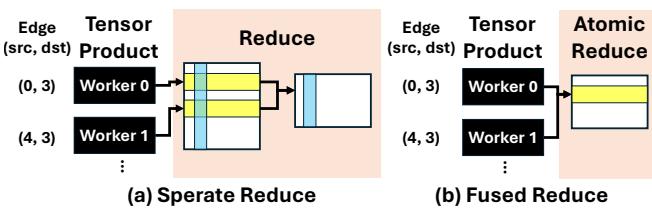

In a standard implementation (like PyTorch or e3nn), the Tensor Product and the subsequent “Reduce” (summing up contributions from neighbors) are separate kernels. The Tensor Product writes a massive tensor to memory, and the Reduce kernel reads it back to sum it up.

FlashTP employs Kernel Fusion. As illustrated in Figure 7, it fuses the Tensor-Product computation directly with the Reduction step.

- Before (a): Each worker calculates its result, writes it to a buffer. Later, a reduction step reads all buffers and sums them.

- After (b): The worker calculates the result and immediately adds it to the destination accumulator in memory using atomic operations (

atomicAdd).

This completely eliminates the need to store the massive intermediate output tensor. This solves both the memory traffic problem and the memory spike problem simultaneously.

2. Exploiting Sparsity

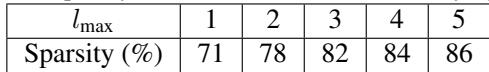

The Clebsch-Gordan (CG) coefficients are constants determined by physics. They tell us how quantum states couple together. Crucially, they are full of zeros.

As shown in Table 1, as the degree (\(l_{max}\)) increases, the sparsity ranges from 71% to 86%. A standard dense matrix multiplication performs operations for all these entries, wasting huge amounts of compute power.

FlashTP implements a custom sparse matrix multiplication optimized for this specific structure.

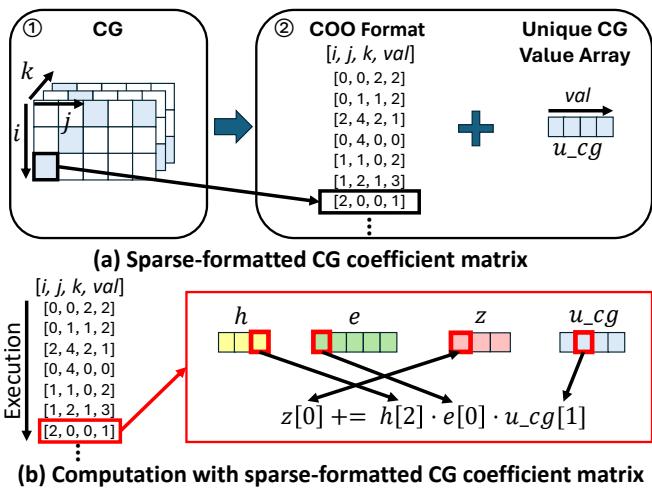

Figure 8 details their approach:

- Storage: They use a Coordinate Format (COO) to store only the non-zero indices \((i, j, k)\).

- Compression: Since many non-zero CG values are duplicates, they store unique values in a small lookup table (

u_cg) and store only the 8-bit index in the matrix. This drastically reduces the memory footprint of the coefficients. - Execution: The kernel iterates only through the non-zero list, performing calculations only where necessary.

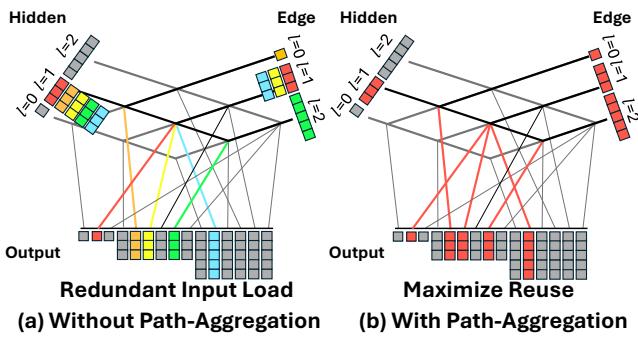

3. Path-Aggregation

After fixing kernel fusion and sparsity, a new bottleneck emerged: reading the input features.

Recall that a Tensor-Product layer consists of many “paths.” For example, hidden features of degree 1 might interact with edge features of degree 1 to produce output degree 0, output degree 1, and output degree 2. That’s three different paths using the exact same input vectors.

In a naive implementation, the GPU reads the input vectors from memory three separate times.

FlashTP introduces Path-Aggregation (Figure 9). By analyzing the computation graph beforehand, FlashTP groups all paths that share the same input components. It loads the input data into the fast GPU register/shared memory once, and then executes all dependent paths back-to-back.

In the example shown in Figure 9, this reduces the number of memory reads for the hidden features by a factor of 5 and for edge features by a factor of 3.

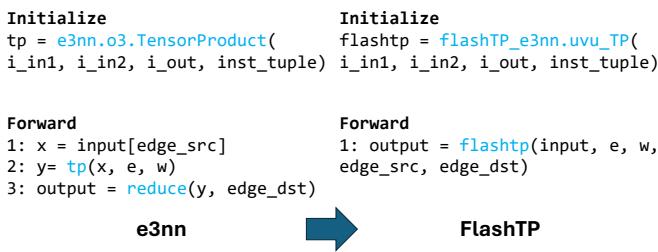

Implementation & Ease of Use

Writing custom CUDA kernels is difficult, and integrating them into high-level Python workflows can be messy. The authors designed FlashTP to be a drop-in replacement for e3nn, the most popular library for equivariant neural networks.

As Figure 10 demonstrates, adopting FlashTP requires minimal code changes. The interface mimics the e3nn.o3.TensorProduct class, preserving the model structure and matrix ordering. This allows researchers to accelerate existing models without rewriting their entire codebase.

Experimental Results

So, how fast is it? The results are impressive across the board.

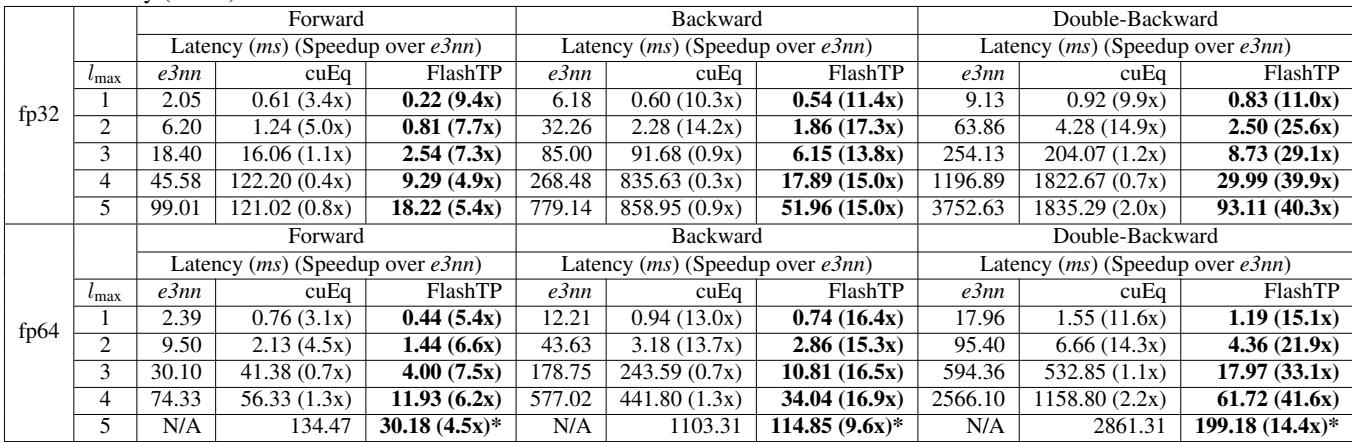

Microbenchmark Speedups

First, looking at the raw kernel performance compared to e3nn and NVIDIA’s own cuEquivariance (cuEq) library:

Table 2 highlights the dominance of FlashTP.

- Forward Pass: Up to 9x faster than e3nn.

- Backward/Double-Backward: This is where FlashTP shines, showing speedups of 20x to 40x. Because the backward passes are heavily memory-bound, the kernel fusion and path aggregation strategies pay massive dividends here.

- Comparison with NVIDIA cuEq: While cuEq is fast for low degrees (\(l_{max}=1,2\)), it struggles to scale. For \(l_{max}=5\), FlashTP is significantly faster, and importantly, avoids the Out-Of-Memory (OOM) errors that plague the baselines.

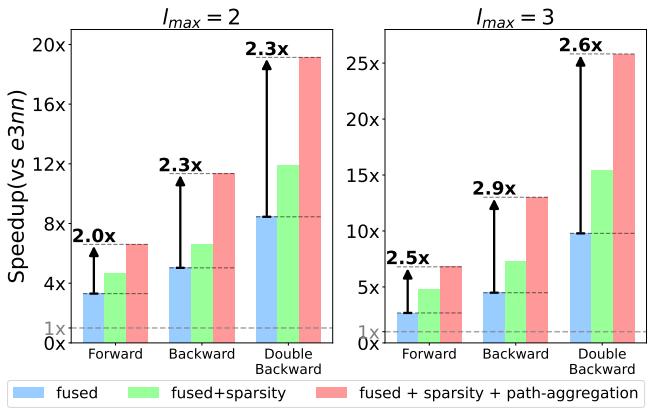

What contributed the most?

An ablation study (Figure 11) breaks down the gains.

- Blue (Fused): Fusion alone provides a solid 3-10x boost.

- Green (Fused + Sparse): Adding sparsity helps significantly in the forward pass where compute is heavier relative to memory.

- Red (Fused + Sparse + Path): Path aggregation (the red bars) provides the final leap, especially in the Double-Backward pass (rightmost cluster), pushing speedups from ~15x to nearly 30x.

Real-World Impact: MD Simulations

Speeding up a kernel is great, but does it help scientists run bigger simulations?

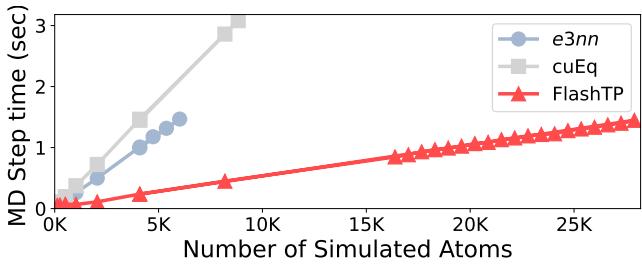

Figure 12 shows the time per MD step as the number of atoms increases.

- e3nn (Blue): Hits a memory wall and crashes (OOM) at roughly 6,000 atoms.

- cuEq (Gray): Scales slightly better but crashes around 9,000 atoms.

- FlashTP (Red): Displays linear scaling and easily handles over 26,000 atoms.

Not only is FlashTP roughly 4.2x faster for a 4,000-atom system, but it also reduces peak memory usage by 6.3x, allowing for simulations of systems that were previously too large to fit on a GPU.

Training Acceleration

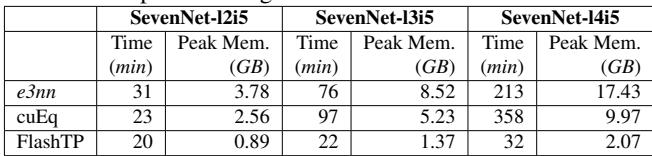

Finally, for researchers training their own potentials, FlashTP drastically cuts down iteration time.

Table 3 shows that training the complex SevenNet-14i5 model (\(l_{max}=4\)) is 6.7x faster with FlashTP than e3nn, dropping per-epoch time from 213 minutes to just 32 minutes. This turns a week-long training run into a single-day job.

Conclusion

FlashTP represents a significant leap forward for Equivariant MLIPs. By treating the Tensor-Product layer as a systems problem rather than just a mathematical one, the authors identified that memory movement, not arithmetic, was the true limit.

Through Kernel Fusion, they minimized memory writes. Through Sparsity awareness, they eliminated useless math. And through Path Aggregation, they maximized data reuse. The result is a library that not only accelerates current models but expands the horizon of what is possible—enabling larger, more complex molecular simulations to run on commodity hardware.

For students and researchers in materials science and machine learning, FlashTP is a powerful tool that removes the computational tax of using highly accurate equivariant models, likely accelerating the discovery of next-generation materials.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/450_flashtp_fused_sparsity_awa-1772/images/cover.png)