Beyond the Lab Bench: Predicting Molecular Behavior in Unknown Solvents with AI

In the world of drug discovery and material science, the environment is everything. A molecule that behaves perfectly in water might act completely differently in ethanol or acetone. This phenomenon, known as solvation, is central to how chemical and pharmaceutical processes work.

Predicting solvation free energy—the energy change when a solute (like a drug molecule) dissolves in a solvent—is a “holy grail” task for computational chemistry. If we can predict this accurately using AI, we can screen millions of drug candidates without stepping into a wet lab.

However, there is a catch. Most current AI models operate under a simplified assumption: that the future will look like the past. They assume the test data comes from the same distribution as the training data (Independent and Identically Distributed, or IID). But in real-world chemistry, we often encounter Out-of-Distribution (OOD) scenarios—new solvents or new molecular structures that the model has never seen before. When traditional models face these unknown environments, they often fail spectacularly.

This article breaks down a recent research paper, “Relational Invariant Learning for Robust Solvation Free Energy Prediction,” which proposes a novel framework called RILOOD. This framework is designed to make AI robust enough to handle these shifts in chemical environments, ensuring that predictions hold true even when the solvent changes.

The Core Problem: The “Solvent Gap”

To understand why this is difficult, we need to look at how traditional Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) approach molecular prediction. Typically, these models look for patterns in the solute molecule—say, a specific ring structure or functional group—and correlate that with a property.

The problem is that these correlations are often spurious. A model might learn that “Molecule X has high solvation energy” because it appeared in a specific solvent during training. If you put Molecule X in a different solvent, that correlation might break. The model is memorizing the specific context rather than understanding the fundamental interaction between the solute and the solvent.

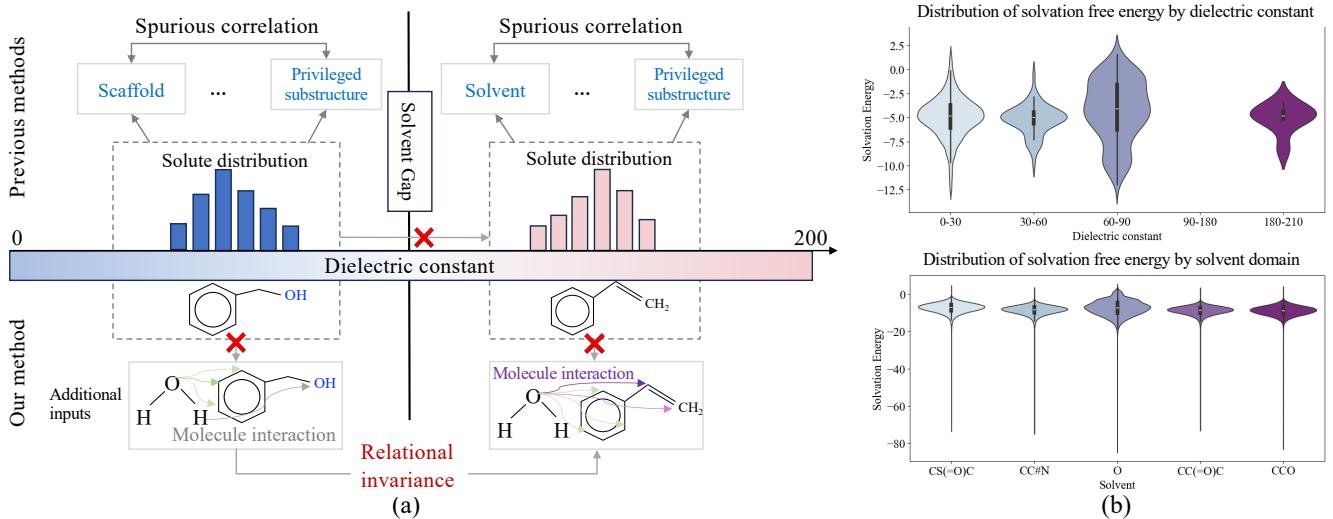

As shown in Figure 1 above, previous methods (left side) often rely on “privileged substructures.” They might see a phenol group and guess the energy based on past data. However, as the dielectric constant (a measure of solvent polarity) changes, the “Solute distribution” shifts dramatically (the dotted boxes). The old correlation fails across the “Solvent Gap.”

The researchers propose a method (right side of Figure 1) that focuses on Relational Invariance. Instead of memorizing static structures, the model looks at the dynamic interactions—like hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces—that remain consistent (invariant) regardless of the specific solvent environment.

The Solution: The RILOOD Framework

The researchers introduce RILOOD (Relational Invariant Learning for Out-of-Distribution Generalization). This is not just a new neural network layer; it is a comprehensive learning strategy designed to strip away environmental bias and find the “true” physical laws governing solvation.

The framework consists of three main pillars:

- Mixup-enhanced Conditional Variational Modeling: To simulate diverse environments.

- Multi-granularity Context-Aware Refinement: To capture interactions at both the atom and molecule levels.

- Invariant Learning Mechanism: To filter out spurious correlations.

Let’s look at the high-level architecture before diving into the specifics.

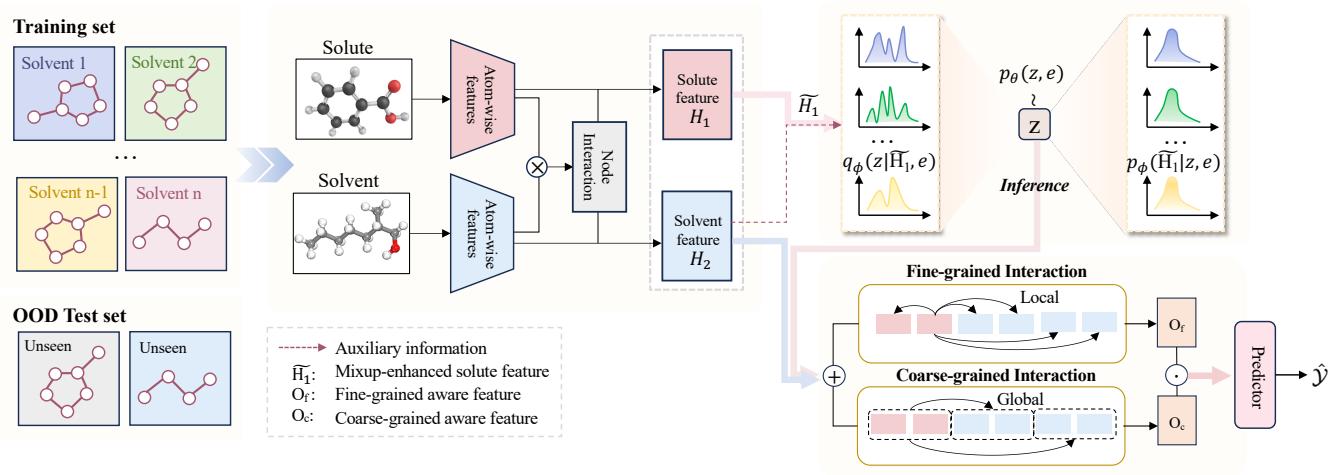

As you can see in Figure 2, the model takes a Solute and a Solvent as input. It processes them through interaction layers and uses auxiliary information to create a robust prediction. Let’s break down the mechanics.

1. Simulating Diverse Environments with Mixup

One of the biggest challenges in OOD generalization is that we don’t always have explicit labels for every possible environmental factor. We know the solvent name, but we might not have a mathematical label for exactly how “different” Acetone is from Ethanol in every context.

To solve this, the authors use a technique called Mixup. Mixup is a data augmentation strategy where you create new, synthetic data points by blending two existing ones. In the context of this paper, they blend the representations of different molecular environments.

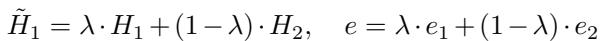

The equation for generating a mixed molecular representation (\(\tilde{H}_1\)) and a mixed environment label (\(e\)) looks like this:

Here, \(\lambda\) (lambda) is a mixing coefficient between 0 and 1. This forces the model to learn a continuous, smooth representation of the environment rather than distinct, rigid categories. It allows the model to “interpolate” between known solvents, making it better at handling unseen solvents that might fall somewhere in between the ones it has trained on.

This mixup strategy is part of a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE). The goal of the CVAE is to infer the latent (hidden) distribution of the solute molecule conditioned on the environment. By optimizing this, the model learns how the molecule’s representation should shift when the environment changes.

2. Multi-granularity Context-Aware Refinement (MCAR)

Standard GNNs often focus heavily on local atomic interactions—how a carbon atom interacts with a nearby oxygen atom. While this is important, solvation is a global phenomenon. The entire solvent creates a “field” around the solute.

The MCAR module is designed to capture interactions at two levels:

- Fine-grained (Local): Detailed atom-to-atom forces.

- Coarse-grained (Global): How the whole solute molecule relates to the solvent context.

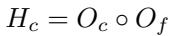

The model calculates a “context-aware” representation, denoted as \(H_c\). It does this by combining global attention mechanisms (which look at long-range dependencies) with local feature transformations.

The combination is achieved via a Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication) of the coarse (\(O_c\)) and fine (\(O_f\)) features:

This ensures that the final representation contains both the specific chemical details and the broader environmental context required to predict solvation energy accurately.

3. Invariant Relational Learning

This is the most theoretical but arguably the most important part of the paper. The goal is to learn a representation that is invariant.

In machine learning terms, an invariant feature is one whose relationship with the target label (solvation energy) does not change, regardless of the environment (solvent). If a feature correlates with energy in Water but not in DMSO, it is a “spurious” feature. If it correlates with energy in both, it is likely a causal, physical feature.

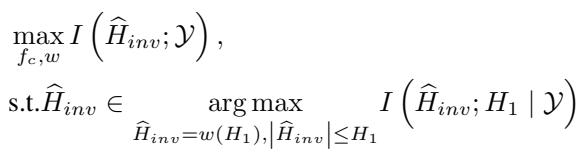

To achieve this, the researchers use Mutual Information (MI) maximization. They want to maximize the mutual information between the learned “invariant” representation (\(\widehat{H}_{inv}\)) and the label, while filtering out noise.

The optimization problem is formulated as:

Essentially, the model is penalized if it relies on features that are specific to just one training environment. It is rewarded for finding the underlying “rules” of interaction that apply universally.

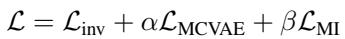

The total loss function (\(\mathcal{L}\)) combines the prediction error (\(\mathcal{L}_{inv}\)), the environmental modeling loss (\(\mathcal{L}_{MCVAE}\)), and the mutual information constraint (\(\mathcal{L}_{MI}\)):

By balancing these three objectives (controlled by weights \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\)), the model creates a prediction engine that is accurate, environment-aware, and chemically robust.

Experimental Results

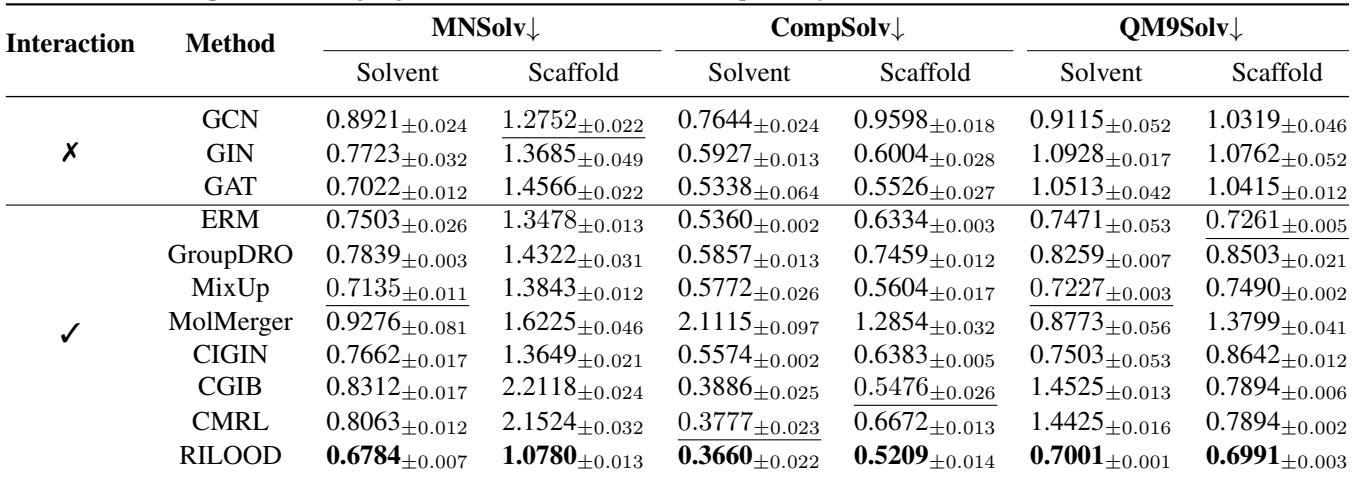

The researchers tested RILOOD against several state-of-the-art baselines, including standard GNNs (like GCN and GAT) and specialized molecular relation learning models (like CIGIN and MolMerger).

They used datasets like MNSolv and QM9Solv, which contain thousands of solute-solvent pairs. Crucially, they didn’t just do a random split of the data. They performed OOD splits:

- Solvent Split: The test set contains solvents that were never seen during training.

- Scaffold Split: The test set contains molecular structures (scaffolds) never seen during training.

Quantitative Performance

The results were compelling. In the table below, RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) is used as the metric—lower numbers are better.

RILOOD (last row) consistently achieves the lowest error rates across almost all categories.

- In the MNSolv Solvent Split, it achieved an RMSE of 0.6784, significantly beating the next best model.

- In the CompSolv Solvent Split, the gap is even wider, showing that RILOOD is particularly good at handling complex solvation environments where traditional models struggle.

This confirms that the “invariant learning” approach prevents the model from overfitting to specific solvents in the training set.

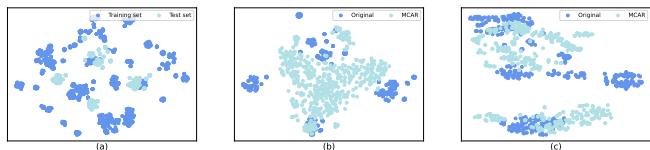

Visualizing Invariance

Numbers are great, but seeing the data distribution helps us understand why the model works better. The researchers used t-SNE (a dimensionality reduction technique) to visualize the learned features of the molecules.

In Figure 4:

- Graph (a) shows the raw distribution shift between training and test sets—they are clearly different, which explains why standard models fail.

- Graph (c) shows the features learned by RILOOD (with the MCAR module). Notice how the clusters are tighter and more distinct compared to the raw data. This indicates that the model has successfully aligned the representations of the training and test data in a shared latent space, effectively “bridging the gap” between the known and the unknown.

Robustness Against Spurious Correlations

The researchers also conducted a “stress test” on synthetic data. They intentionally injected spurious correlations—fake patterns that link specific environments to labels—to see if the models would be tricked.

As the strength of these fake correlations increased, most baseline models improved their performance falsely (by cheating and learning the fake pattern). RILOOD, however, remained stable. This proves that the mutual information constraints successfully force the model to ignore statistical coincidences and focus on physical reality.

Conclusion and Implications

The RILOOD framework represents a significant step forward in “AI for Science.” By moving beyond simple pattern matching and incorporating concepts like environmental invariance and multi-granularity interactions, the authors have created a tool that mirrors the way chemists actually think.

Key takeaways for students and practitioners:

- OOD is the Norm: In scientific discovery, we are almost always trying to predict something we haven’t seen before. Models must be designed for Out-of-Distribution generalization, not just IID accuracy.

- Context Matters: A molecule does not exist in a vacuum (usually). Modeling the environment (solvent) is just as important as modeling the object (solute).

- Invariance is Key: To build robust models, we must separate stable, causal relationships from temporary, environmental biases.

This approach opens the door for more reliable high-throughput screening of drugs and materials, potentially saving years of experimental time by accurately predicting which molecules will dissolve, react, and function in complex real-world environments.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/496_relational_invariant_learn-1773/images/cover.png)