Introduction

In the last few years, we have witnessed a massive leap in the capabilities of Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs). Models like GPT-4o and Gemini can describe a photo of a busy street, write code from a whiteboard sketch, or explain a meme. However, when we shift our gaze from general internet images to the high-stakes world of medicine, these “foundation models” often hit a wall.

Why? Because medical diagnosis isn’t just about identifying objects. It is about reasoning.

If you show a general LVLM a medical scan, it might correctly identify it as a brain MRI. It might even spot a large tumor. But ask it a professional-level question—like “Based on the lesion pattern in the basal ganglia, what is the predicted neurocognitive outcome for this neonate in two years?"—and the model crumbles.

This is the problem tackled by a fascinating new paper titled “Visual and Domain Knowledge for Professional-level Graph-of-Thought Medical Reasoning.” The researchers argue that to make AI useful in clinical settings, we need to move beyond simple Visual Question Answering (VQA) and towards models that mimic the step-by-step reasoning process of a human specialist.

In this deep dive, we will explore how they constructed a new benchmark for “hard” medical problems and developed a novel method called Clinical Graph of Thoughts (CGoT) to solve them.

The Gap in Medical AI

To understand the innovation of this paper, we first need to look at the current state of Medical Visual Question Answering (MVQA).

Most existing datasets for medical AI focus on what clinicians consider “easy” or “irrelevant” tasks. For example, a dataset might ask the model to identify the organ in an image or the imaging modality (e.g., “Is this a CT or an MRI?”). While these are necessary first steps, they are not tasks that a doctor needs help with. A radiologist knows they are looking at a brain MRI.

What doctors need is assistance with complex prognostics and decision-making.

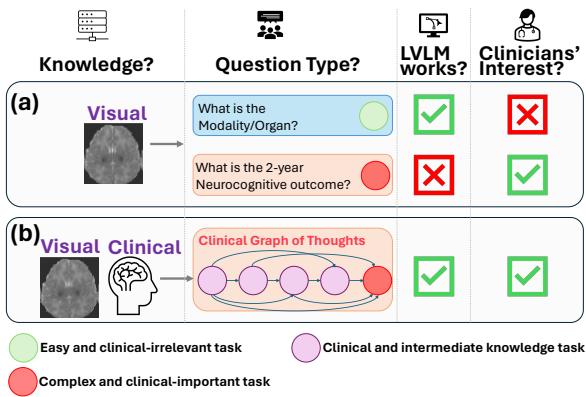

As shown in Figure 1, there is a misalignment between what AI is currently tested on (Scenario A) and what clinicians actually care about (Scenario B). The researchers identified that while LVLMs can handle simple perception tasks, they fail at the complex, clinically important tasks—represented by the red circles—such as predicting a patient’s long-term health outcome.

Enter the HIE-Reasoning Benchmark

To bridge this gap, the authors introduced a new benchmark called HIE-Reasoning. This dataset focuses on a specific, critical medical condition: Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE).

HIE is a type of brain dysfunction that occurs when a newborn infant doesn’t receive enough oxygen and blood flow to the brain around the time of birth. It is a leading cause of death and disability in neonates. Diagnosing the severity of HIE and predicting whether a baby will suffer from long-term issues (like cerebral palsy or cognitive deficits) is incredibly difficult and requires expert synthesis of MRI data.

Why this Benchmark is Different

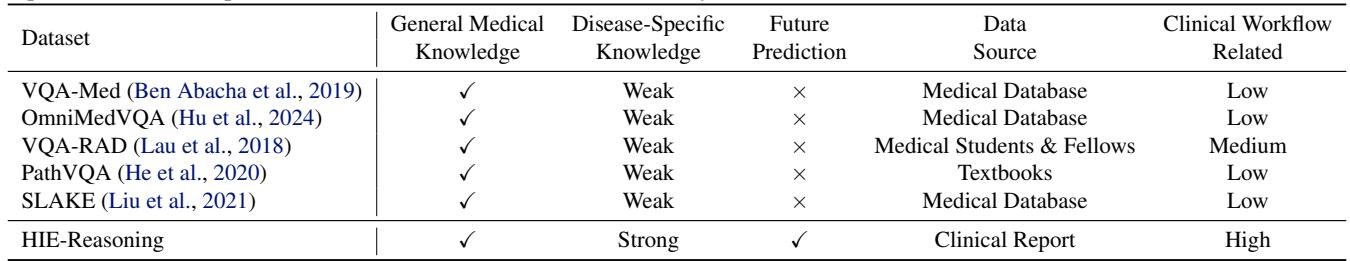

Most medical datasets are scraped from public databases and labeled by general annotators. HIE-Reasoning, however, was built using real clinical reports and expert annotations from a decade of data (2001–2018).

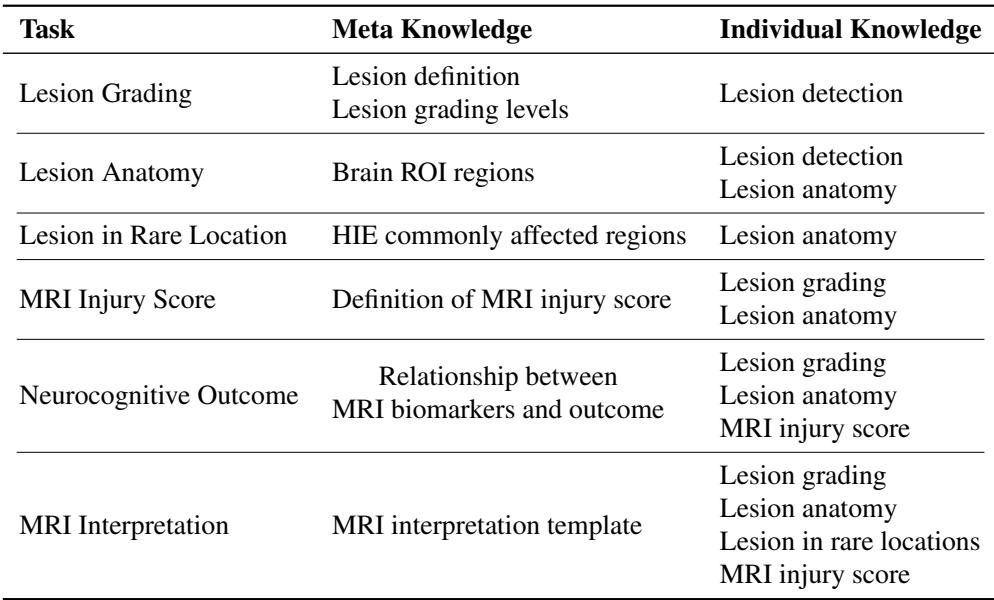

As illustrated in Table 1, HIE-Reasoning is unique because it demands future prediction. The AI isn’t just describing what is currently on the screen; it must predict the neurocognitive outcome of the patient two years into the future. This is the “Holy Grail” of clinical decision support.

The Six Tasks of HIE-Reasoning

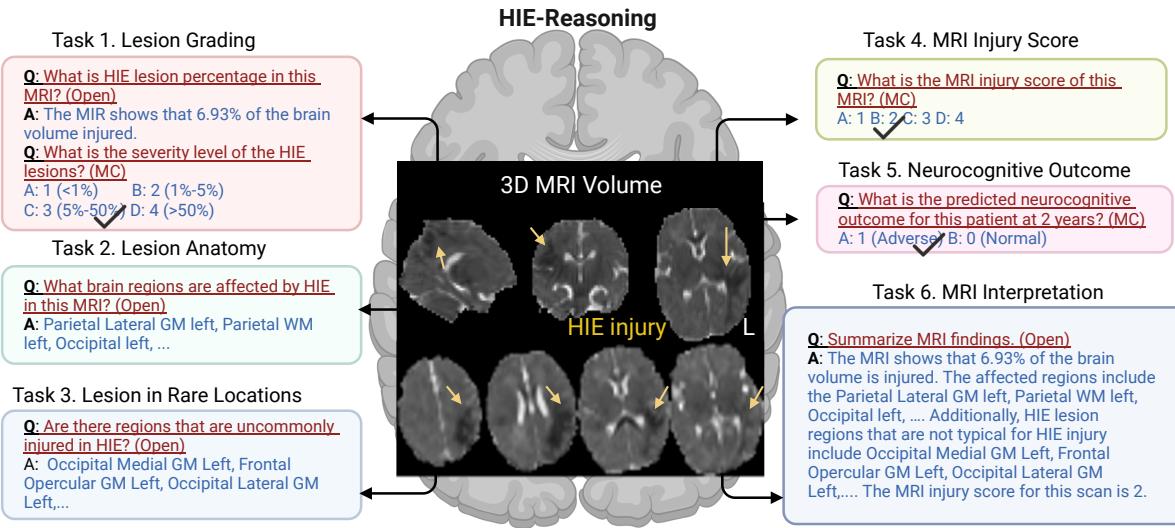

The benchmark isn’t a single question. It is structured to simulate a full clinical workflow. The researchers defined six specific tasks that an AI must perform, mirroring the steps a radiologist and neonatologist would take:

- Lesion Grading: Estimating the percentage of brain volume injured and the severity level.

- Lesion Anatomy: Identifying which specific brain regions (ROIs) are damaged.

- Lesion in Rare Locations: Determining if the injury pattern is typical or atypical.

- MRI Injury Score: Assigning a standardized clinical score (NRN score) used in hospitals.

- Neurocognitive Outcome Prediction: The ultimate goal—predicting if the outcome at 2 years will be normal or adverse.

- MRI Interpretation Summary: generating a cohesive text report.

Figure 2 visualizes this ecosystem. By breaking the diagnosis down into these constituent parts, the benchmark forces the model to demonstrate understanding at every level of the analysis.

The Solution: Clinical Graph of Thoughts (CGoT)

The researchers found that if you simply feed an MRI into a standard LVLM (like GPT-4o) and ask “What is the 2-year outcome?”, the model performs poorly—often no better than a random guess. The model lacks the domain expertise to connect the visual patterns to a complex prognosis.

To solve this, they proposed the Clinical Graph of Thoughts (CGoT) model.

What is a Graph of Thoughts?

In AI prompting, “Chain of Thought” is a technique where you ask the model to “think step-by-step.” “Graph of Thoughts” takes this further by modeling the reasoning process as a network of interconnected nodes, rather than just a linear line.

In CGoT, the “nodes” of the graph correspond to the clinical tasks we just discussed. The model solves the easy tasks first, and passes that information (the “thought”) to the next node to help solve the harder tasks.

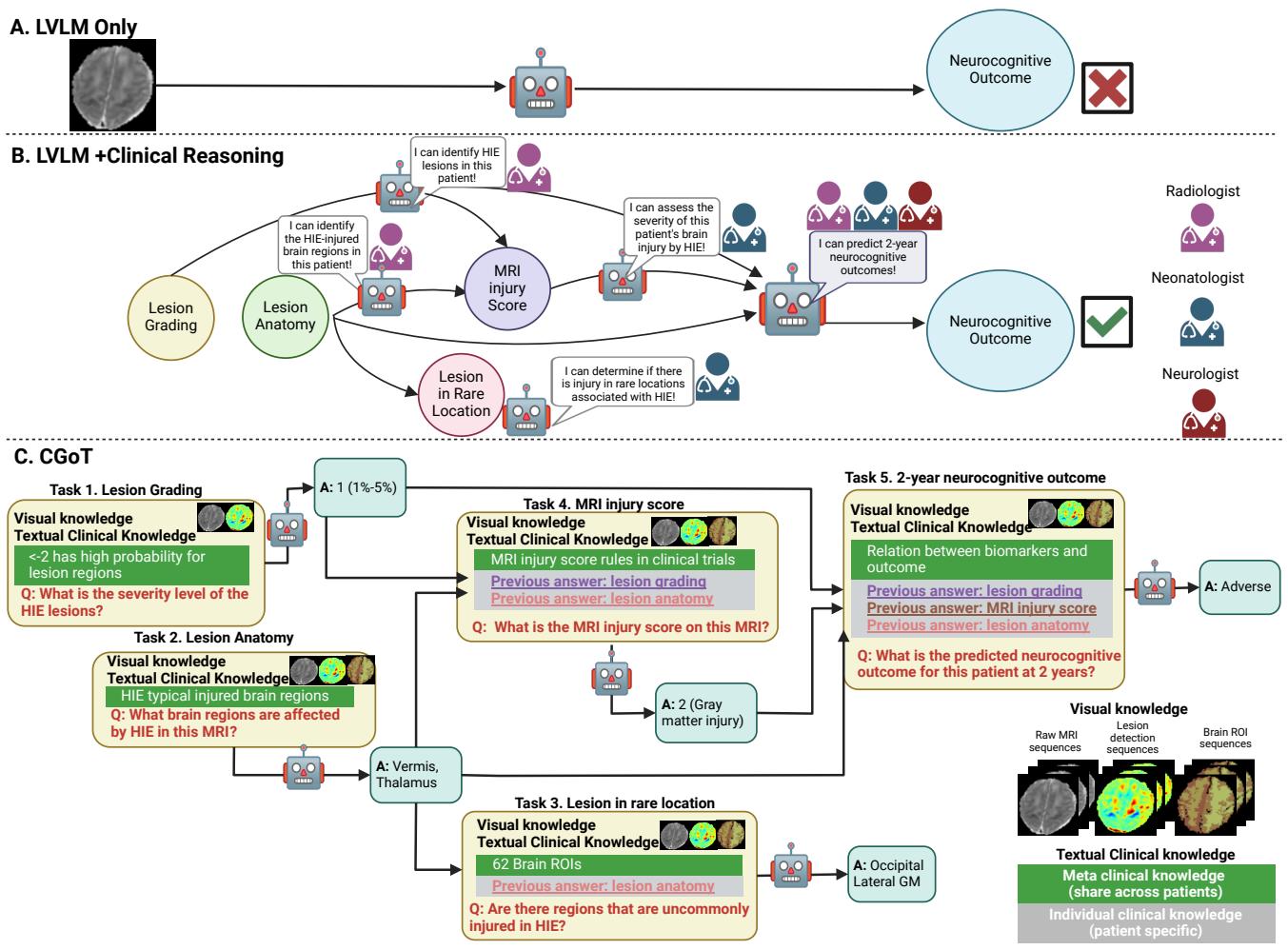

Figure 3 offers a clear comparison.

- Approach A is the naive method: Image \(\rightarrow\) Model \(\rightarrow\) Prediction. It fails.

- Approach C is CGoT. It mimics a doctor who first assesses the severity (Lesion Grading), then checks where the damage is (Anatomy), then assigns a clinical score, and only then makes a prediction about the future.

Fueling the Graph: Visual and Textual Knowledge

For this graph to work, the model needs more than just raw pixels. It needs Domain Knowledge. The authors feed the model two distinct types of information:

1. Visual Knowledge

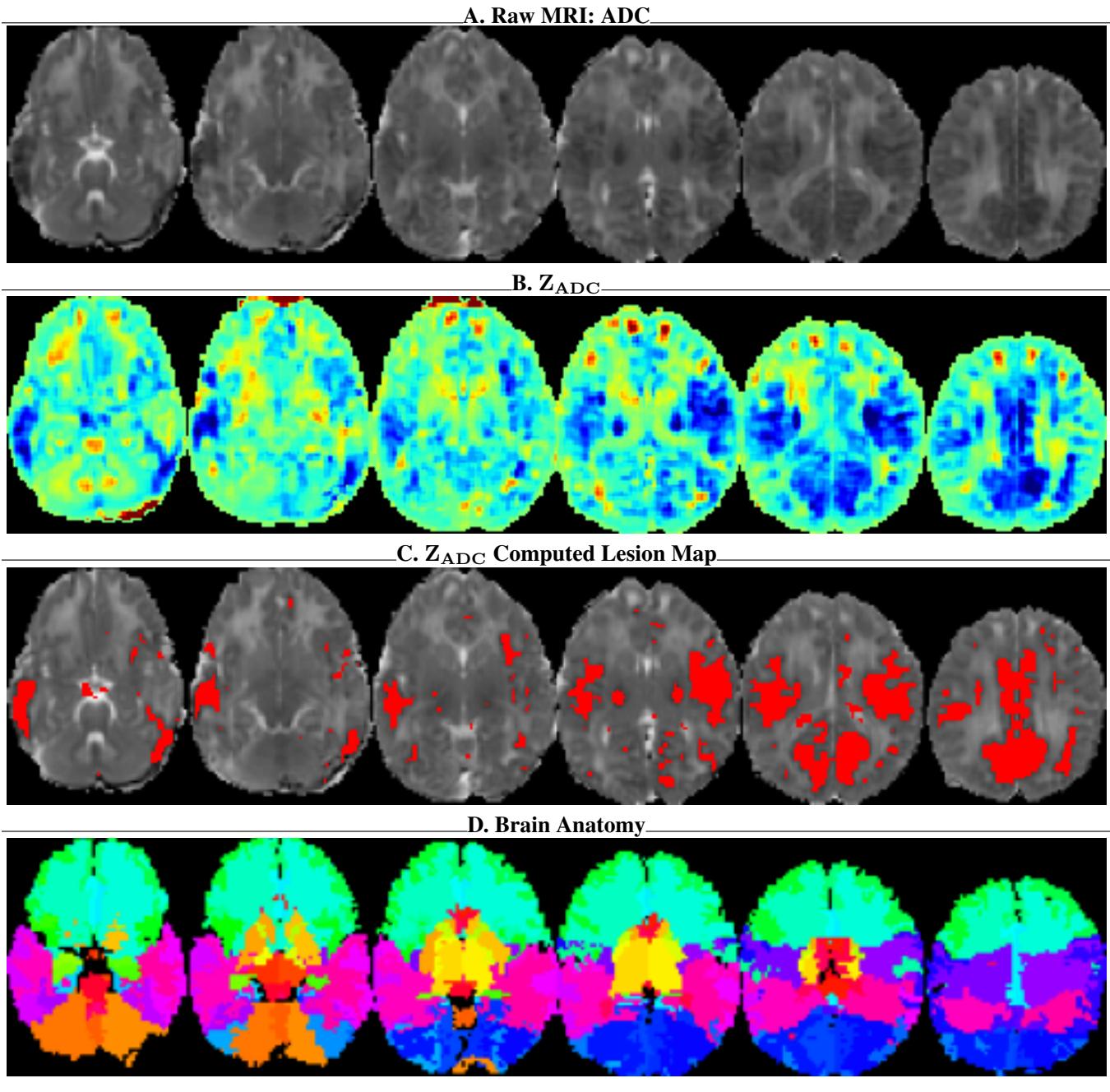

Raw MRI scans are difficult for AI to interpret because “normal” intensity varies between patients. The authors augment the raw data with:

- \(Z_{ADC}\) Maps: A statistical normalization that highlights exactly how much a pixel deviates from a “healthy” brain.

- Lesion Probability Maps: A heatmap showing likely injury sites.

- Brain Anatomy Maps: An overlay that labels the 62 specific regions of interest (ROIs) in the brain.

As seen in Figure 7, providing the model with the anatomy map (Panel D) and the statistical deviation map (Panel B) essentially gives the AI “radiologist vision,” allowing it to see structures and anomalies that might be invisible in the raw gray pixels.

2. Textual Knowledge

The model is also fed textual prompts divided into Meta Knowledge and Individual Knowledge.

- Meta Knowledge: This is general medical textbook information (e.g., “The basal ganglia are commonly affected in HIE”).

- Individual Knowledge: This is the patient-specific information generated by previous steps in the graph (e.g., “This specific patient has a lesion in the left thalamus”).

Experiments and Results

So, does thinking like a doctor actually help the AI perform better? The results are compelling.

Comparison with State-of-the-Art

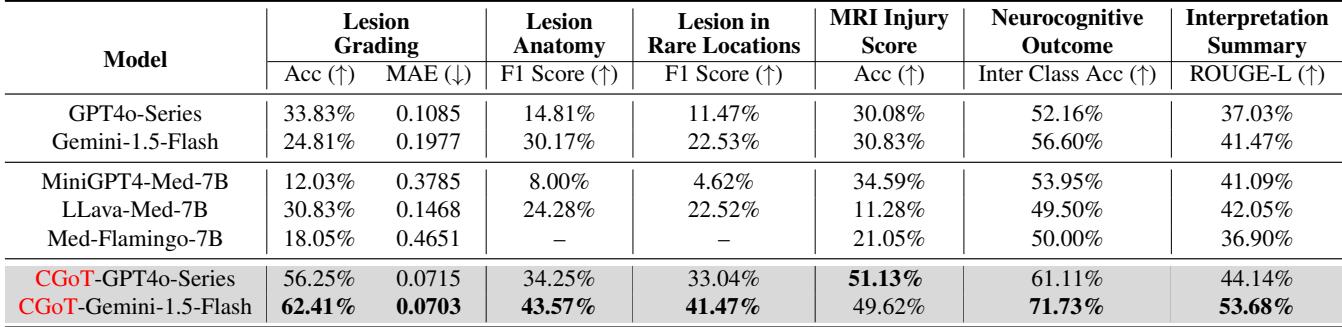

The authors tested standard models (GPT-4o, Gemini, Med-Flamingo) against their CGoT approach.

Table 2 reveals the stark difference.

- Baselines: Standard models struggled significantly. For the crucial “Neurocognitive Outcome” task, models like LLava-Med and Med-Flamingo hovered around 50% accuracy—essentially a coin flip. Even the powerful GPT-4o series only achieved 52.16%.

- CGoT: When wrapped in the CGoT framework, Gemini-1.5-Flash shot up to 71.73% accuracy on the outcome prediction task. This is a massive improvement, demonstrating that the reasoning structure matters just as much as the underlying model.

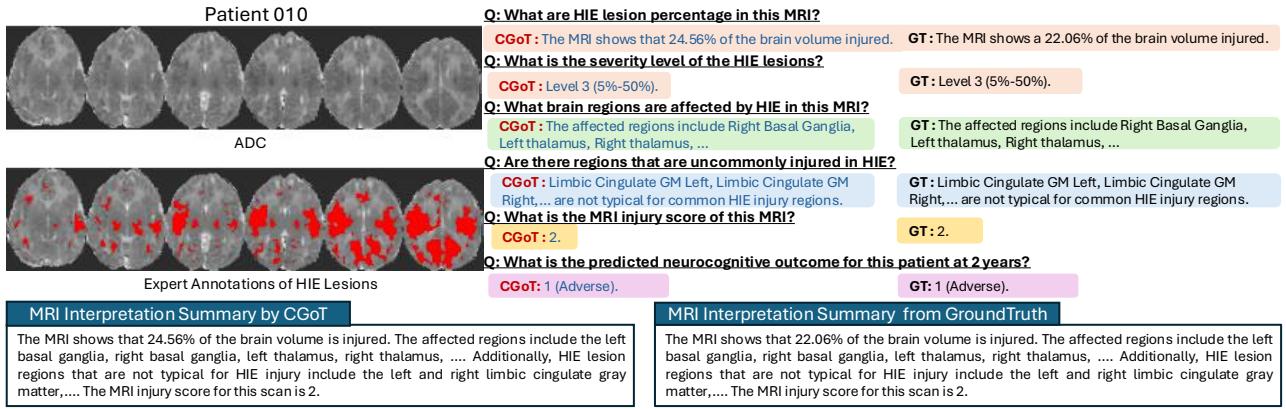

Qualitative Analysis

The numbers are good, but the transparency is even better. Because CGoT works in steps, we can inspect its “thought process.”

Figure 4 shows a generated report for “Patient 010.” Notice how the model correctly identifies the “Right Basal Ganglia” and “Left Thalamus” as affected regions. Because it identified these critical areas in the “Lesion Anatomy” step, it was able to correctly calculate the MRI Injury Score as “2,” which led it to the correct prediction of an “Adverse” outcome. A black-box model might have gotten the prediction right or wrong, but it couldn’t tell you why.

Why does it work? (Ablation Studies)

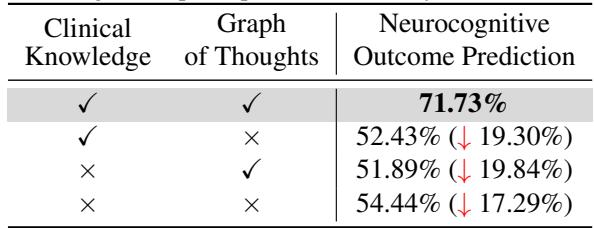

The researchers performed “ablation studies” to verify if every part of their complex graph was necessary.

1. Do we need the Graph? Yes. As shown in Table 3, removing the “Graph of Thoughts” (reasoning steps) dropped the accuracy from 71.73% down to 52.43%.

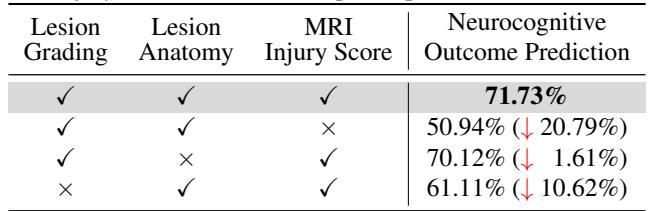

2. Which step is most critical? They found that the MRI Injury Score step was the linchpin. If they removed that specific node from the graph, accuracy plummeted by over 20%.

This makes perfect clinical sense. The MRI Injury Score (specifically the NRN score mentioned in the paper) is the standard biomarker used by human doctors to predict outcomes. By forcing the AI to calculate this score explicitly, the researchers aligned the AI’s “latent space” with established medical science.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Visual and Domain Knowledge for Professional-level Graph-of-Thought Medical Reasoning” represents a significant shift in Medical AI. It moves away from the idea that we just need “bigger models” and towards the idea that we need better reasoning structures.

By creating the HIE-Reasoning benchmark, the authors provided a testing ground for professional-level medical tasks involving prognosis and future prediction. By developing CGoT, they showed that decomposing a complex medical problem into a graph of smaller, clinically relevant sub-tasks allows General LVLMs to perform like specialists.

Key Takeaways:

- Context Matters: Feeding raw pixels to an AI is often insufficient for medical diagnosis. Models need statistical context (like \(Z_{ADC}\) maps) and anatomical context (ROI maps).

- Process Mimicry: AI performs best when its inference process mirrors the workflow of human experts (Grading \(\rightarrow\) Anatomy \(\rightarrow\) Scoring \(\rightarrow\) Prediction).

- Explainability: Graph-based reasoning doesn’t just improve accuracy; it generates an audit trail. If the model makes a wrong prediction, we can look at the intermediate nodes to see where it went wrong (e.g., did it miss a lesion in the thalamus?).

This work suggests a future where AI acts not just as a pattern recognizer, but as a transparent, reasoning partner in the high-stakes environment of neonatal care.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/5576_visual_and_domain_knowled-1759/images/cover.png)