In the modern era of Artificial Intelligence, data is the new oil. But unlike oil, data often comes with strings attached: privacy regulations. With the enforcement of laws like the European Union’s GDPR and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), individuals have gained the “right to be forgotten.” This means that if a user requests their data be deleted, any machine learning model trained on that data must theoretically “unlearn” it.

This process is called Machine Unlearning. Ideally, we would simply delete the data and retrain the model from scratch. However, retraining large models is computationally expensive and time-consuming. Consequently, researchers have developed algorithms to scrub specific data points from a trained model without a full reset.

But there is a catch—a paradox, even. Most existing unlearning methods require access to the original training data to calculate what needs to be removed and what needs to be preserved. What happens if you can’t access the original data? In many real-world scenarios, training data is deleted immediately after use for privacy compliance, or it is too massive to store indefinitely.

This scenario is known as Source-Free Unlearning, and it is one of the hardest challenges in the field today.

In this post, we will deep dive into a research paper that proposes a novel solution to this problem: the Data Synthesis-based Discrimination-Aware (DSDA) framework. This method allows models to unlearn information efficiently without ever seeing the original training set again.

The Source-Free Challenge

Before understanding the solution, we need to grasp the specific constraints of the problem.

- The Goal: Remove the influence of a specific subset of classes (Forget Data, \(D_f\)) from a pre-trained model.

- The Constraint: We do not have access to the original training dataset (\(D_{train}\)). We only have the pre-trained model weights (\(\theta_o\)) and the class labels.

- The Barrier: Existing source-free methods often rely on Knowledge Distillation (training a student model to mimic a teacher), which is computationally heavy and slow.

The authors of the DSDA framework propose a two-stage approach that mimics the original data and then optimizes the model to forget specific parts of it.

Figure 1: The architecture of the DSDA framework. It operates in two stages: (1) Generating synthetic data to replace the missing training set, and (2) Optimizing the model using a multitask approach to unlearn specific classes while preserving others.

Figure 1: The architecture of the DSDA framework. It operates in two stages: (1) Generating synthetic data to replace the missing training set, and (2) Optimizing the model using a multitask approach to unlearn specific classes while preserving others.

As shown in Figure 1, the framework is split into Accelerated Energy-Guided Data Synthesis (AEGDS) and Discrimination-Aware Multitask Optimization (DAMO). Let’s break these down.

Stage 1: Accelerated Energy-Guided Data Synthesis (AEGDS)

If we don’t have the data, we have to make it. But we can’t just feed random noise into the model; we need data that looks statistically similar to the original training set so the model can distinguish between what to keep and what to delete.

The authors propose using the pre-trained model itself to generate this data. Since the model has learned the features of the data, it effectively contains a “memory” of the distribution.

The Energy-Based Perspective

The researchers reinterpret the classifier as an Energy-Based Model (EBM). In physics and machine learning, an energy function \(E(x)\) assigns a scalar value to a state \(x\). Lower energy states are more stable and probable.

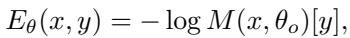

By defining an energy function based on the model’s output logits, samples that the model is confident about (high probability) will have low energy. The energy function is defined as:

Here, \(M(x, \theta_o)[y]\) is the probability the model assigns to input \(x\) for class \(y\). By minimizing this energy, we can find an input \(x\) that looks like a valid sample for class \(y\).

Langevin Dynamics and the Need for Speed

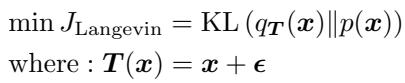

To generate these samples, the authors utilize Langevin Dynamics. This is an iterative process that starts with random noise and slowly updates it by following the gradient of the energy function (moving toward high-probability regions) while adding a bit of noise to explore the space.

The standard update rule for finding a transformation \(T(x)\) that maps a distribution \(q\) to a target \(p\) is derived from minimizing KL-Divergence:

However, standard Langevin Dynamics is slow. It requires many steps to converge to a realistic image, and calculating gradients at every single step is computationally expensive. This slowness makes it impractical for efficient unlearning.

The “Accelerated” Solution

To fix this, the authors introduce AEGDS. They treat the sampling process as a differential equation and use advanced numerical solvers to speed it up.

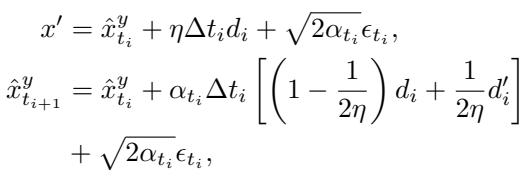

1. Runge-Kutta Integration: Instead of simple steps, they use a second-order Runge-Kutta method (specifically Heun’s method). This allows the synthesizer to take larger steps with higher accuracy, effectively skipping redundant intermediate computations.

In this equation:

- \(d_i\) is the direction derived from the gradient at the current step.

- \(d'_i\) is a “look-ahead” gradient estimate.

- This two-stage estimation results in a much more accurate update for the synthetic image \(\hat{x}\).

2. Nesterov Momentum: To further speed up convergence, they add a momentum term. Just like a ball rolling down a hill gains speed, the optimization “remembers” its previous direction (\(v_i\)) to move faster through flat regions of the energy landscape.

By combining these techniques, the DSDA framework can rapidly generate two synthetic datasets: \(\hat{D}_r\) (synthetic data for classes we want to retain) and \(\hat{D}_f\) (synthetic data for classes we want to forget).

Stage 2: Discrimination-Aware Multitask Optimization (DAMO)

Now that we have synthetic data, we can proceed to the actual unlearning. Standard unlearning usually involves two simple goals:

- Maximize error on the forget set (make the model bad at identifying the forgotten class).

- Minimize error on the retain set (keep the model good at everything else).

However, the authors found that simply applying these two forces causes a problem called feature scattering.

The Problem of Feature Distribution

When you force a model to “forget” a class, it disrupts the model’s internal feature space.

Figure 2: Comparing feature spaces. (a) The original model. (b) A model retrained from scratch (the gold standard). (c) A model unlearned with standard loss functions. (d) A model unlearned with DSDA.

Figure 2: Comparing feature spaces. (a) The original model. (b) A model retrained from scratch (the gold standard). (c) A model unlearned with standard loss functions. (d) A model unlearned with DSDA.

Look at Figure 2(c). This shows the result of standard unlearning. Notice how the dots (representing data samples) are scattered? The classes are not well-separated. This means the model has become confused, likely reducing its accuracy on the data it was supposed to keep.

Compare that to Figure 2(b), which is the “Retrained” model (what we aspire to be). Here, the clusters are tight and distinct.

The Discriminative Feature Alignment Objective

To fix the scattering issue seen in 2(c), the authors introduce a new loss function: Discriminative Feature Alignment.

The goal is twofold:

- Intra-class Compactness: Pull samples of the same retain class closer together.

- Inter-class Separability: Push samples of different retain classes further apart.

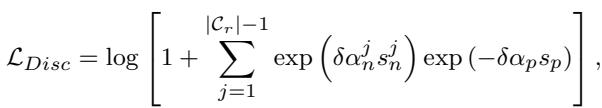

The mathematical formulation for this objective is:

This loss function (\(\mathcal{L}_{Disc}\)) uses cosine similarity (\(s\)) to penalize the model if different classes get too close (\(s_n^j\)) or if the same class spreads out too much (\(s_p\)).

The result is visible in Figure 2(d). The DSDA unlearned model maintains tight, separated clusters, looking very similar to the retrained model in Figure 2(b).

Multitask Optimization: Solving Gradient Conflicts

We now have three distinct objectives to optimize:

- Forget Loss (\(\mathcal{L}_F\)): Destroy knowledge of the target class.

- Retain Loss (\(\mathcal{L}_R\)): Preserve knowledge of other classes.

- Discriminative Loss (\(\mathcal{L}_{Disc}\)): Keep the feature space tidy.

Optimizing these simultaneously is difficult because their gradients often conflict. For example, the gradient update to help the model “forget” might accidentally push the weights in a direction that destroys the compactness of the “retain” classes.

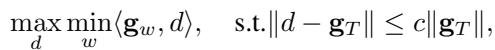

To solve this, the authors treat it as a Multitask Optimization problem. They seek an update direction \(d\) that satisfies all three objectives as best as possible.

This equation essentially asks: What is the best direction \(d\) that maximizes the improvement on the “worst-performing” objective, while not deviating too far from the overall average gradient (\(\mathbf{g}_T\))?

By solving this Lagrangian optimization problem (Theorem 3.3 in the paper), they derive a dynamic weighting system that adjusts the importance of each loss function on the fly, ensuring a stable and balanced unlearning process.

Experiments and Results

The authors tested DSDA on three benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and PinsFaceRecognition (for face recognition tasks). They compared it against several baselines, including “Retrained” (the ideal upper bound) and other source-free methods like GKT and ISPF.

Effectiveness: Accuracy and Privacy

The primary metrics for success are:

- \(A_f\) (Accuracy on Forget Data): Should be 0% (total amnesia).

- \(A_r\) (Accuracy on Retain Data): Should be high (close to the original model).

- MIA (Membership Inference Attack): A lower score is better; it indicates that an attacker cannot determine if the specific data was used in training.

Table 1: Single-class unlearning results. Notice DSDA achieves 0.00% on Forget Accuracy (\(A_f\)) while maintaining the highest Retain Accuracy (\(A_r\)) among source-free methods.

Table 1: Single-class unlearning results. Notice DSDA achieves 0.00% on Forget Accuracy (\(A_f\)) while maintaining the highest Retain Accuracy (\(A_r\)) among source-free methods.

As seen in Table 1, DSDA (bottom row) consistently outperforms other source-free methods. It effectively wipes the memory of the target class (\(A_f = 0.00\)) while keeping the retain accuracy (\(A_r\)) nearly identical to the original model. Crucially, its MIA score is very low (11.80%), suggesting high privacy protection.

Efficiency: Speed Matters

One of the main selling points of DSDA is “Accelerated” synthesis. Does it hold up?

Figure 3: Efficiency comparison. The x-axis represents execution time (ET), and the y-axis represents Retain Accuracy (\(A_r\)).

Figure 3: Efficiency comparison. The x-axis represents execution time (ET), and the y-axis represents Retain Accuracy (\(A_r\)).

In Figure 3, we see that DSDA (the red line) achieves high accuracy almost immediately. Competing methods like ISPF (blue) and GKT (green) take significantly longer to reach decent accuracy levels, or never reach them at all. This proves that the Runge-Kutta and Momentum integration in Stage 1 pays off significantly.

Does Synthetic Data Compromise Privacy?

A valid concern with generating synthetic data is that we might accidentally reconstruct the actual face or image of a user, violating the very privacy we are trying to protect.

The authors visualized the synthetic data generated by their AEGDS process:

Figure 5: (a) Feature distribution overlap between real and synthetic data. (b) What the synthetic data actually looks like.

Figure 5: (a) Feature distribution overlap between real and synthetic data. (b) What the synthetic data actually looks like.

Figure 5(b) shows that the synthetic images are visually unrecognizable noise patterns. They capture the statistical features required for the model (as shown by the overlapping clusters in 5(a)), but they do not reveal any human-interpretable information. This ensures the unlearning process itself remains privacy-preserving.

Conclusion

The DSDA framework represents a significant step forward in privacy-centric machine learning. By successfully decoupling unlearning from the need for original data, it offers a viable path for companies and researchers to comply with “right to be forgotten” regulations without incurring massive computational costs or storage liabilities.

The two-stage innovation—first effectively “hallucinating” the necessary statistical data using accelerated energy models, and then meticulously organizing the feature space via multitask optimization—demonstrates that we don’t always need the original data to correct a model’s behavior. We just need to understand the model’s internal energy and feature representations well enough to guide it.

As privacy laws become stricter, techniques like DSDA will likely move from academic papers to standard practice in MLOps pipelines worldwide.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/5707_efficient_source_free_unl-1760/images/cover.png)