In the world of computer science and operations research, scaling is the ultimate boss fight. Solving a logistics problem with ten delivery trucks is a homework assignment; solving it with ten thousand trucks, changing traffic conditions, and time windows is a computational nightmare.

These massive challenges are often framed as Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problems. While we have powerful commercial solvers like Gurobi and SCIP, they often hit a wall as problem sizes explode. The search space grows exponentially, making exact solutions impossible to find in a reasonable timeframe.

For years, researchers have relied on heuristics—shortcuts or “rules of thumb”—to find good-enough solutions quickly. But designing these heuristics requires deep expert knowledge and months of trial and error. Recently, we’ve seen Machine Learning (ML) attempt to learn these heuristics, but deep learning models often struggle with generalization and require massive, expensive training datasets.

Enter LLM-LNS, a new framework presented in a 2025 paper by researchers from Tsinghua University. This approach essentially asks: What if, instead of training a neural network to solve the problem, we ask a Large Language Model (LLM) to write the code for the solving algorithm itself?

In this deep dive, we will explore how LLM-LNS utilizes a dual-layer self-evolutionary agent to automate the design of optimization algorithms, achieving state-of-the-art results on massive scales with minimal training data.

The Core Problem: MILP and the Search for Neighborhoods

Before dissecting the solution, let’s establish the problem. A Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem looks like this mathematically:

You are trying to minimize a cost (\(c^Tx\)) subject to constraints (\(Ax \leq b\)), where some variables must be integers (\(x_i \in \mathbb{Z}\)).

The Limits of Exact Solvers

Exact algorithms like Branch-and-Bound try to explore the tree of possible integer combinations. For small problems, they are perfect. For large-scale problems (e.g., millions of variables), they are computationally infeasible.

The LNS Alternative

To handle scale, practitioners use Large Neighborhood Search (LNS). The logic is intuitive:

- Start with a solution (even a bad one).

- Destroy: Fix most of the variables to their current values, but “free” a small subset of them. This creates a “neighborhood.”

- Repair: Use an exact solver to optimize just that small free subset.

- Repeat until the solution is good.

The million-dollar question in LNS is: Which variables do you free? If you pick random variables, the solver won’t find improvements. You need a smart strategy to select a “neighborhood” that likely contains a better solution. Designing that strategy usually requires a PhD in Operations Research.

Enter LLM-LNS: Automating Algorithm Design

The researchers propose LLM-LNS, a framework where an LLM acts as an intelligent agent to generate the neighborhood selection strategy (the code that picks which variables to free).

This is not a static process. The LLM doesn’t just write code once; it evolves it. The framework functions like a biological evolution simulator, where the “organisms” are Python functions and “fitness” is how well those functions solve MILP problems.

The System Architecture

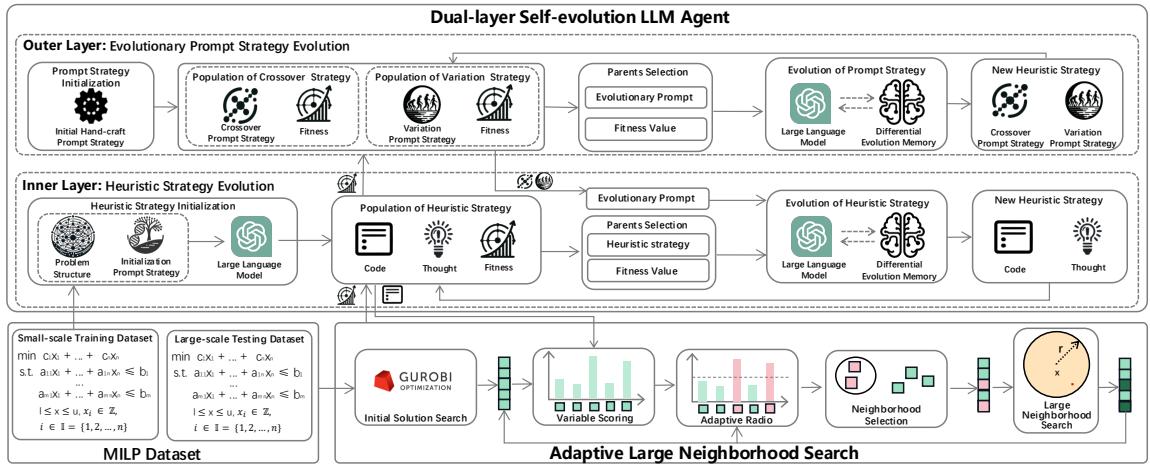

The architecture is novel because it splits the evolutionary process into two distinct layers.

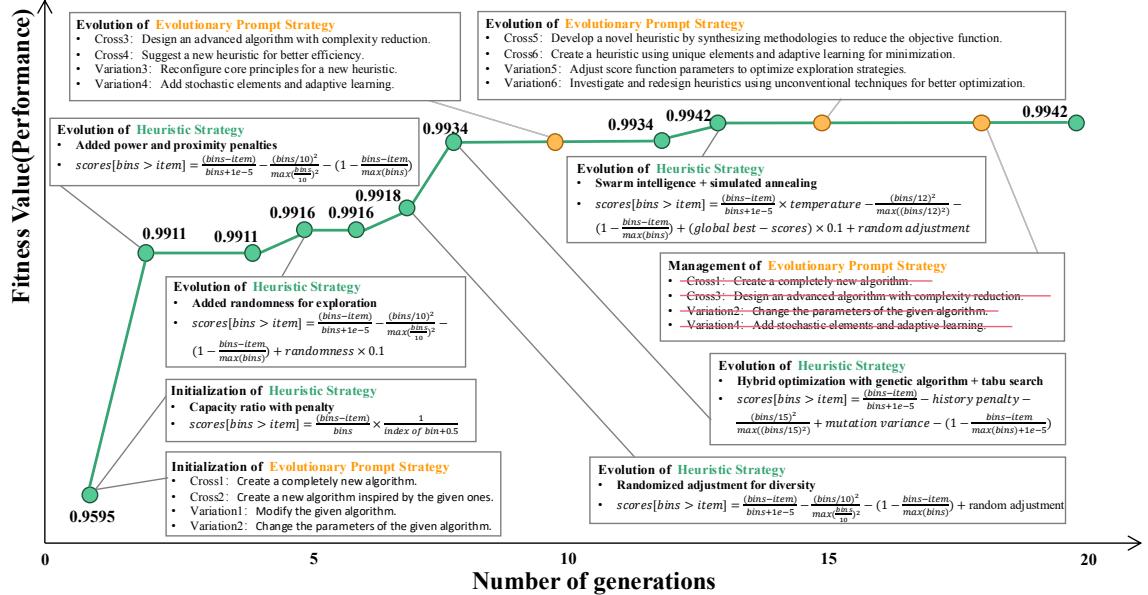

As shown in Figure 1 above, the framework consists of:

- Outer Layer (The Strategist): Evolves Prompt Strategies. It figures out how to ask the LLM for better code (e.g., “Try focusing on variables with high costs” vs. “Try adding randomness”). This maintains diversity.

- Inner Layer (The Executor): Evolves Heuristic Strategies. It takes the prompts and writes the actual Python code. It iterates quickly to converge on a working algorithm.

- Differential Memory: A feedback loop that helps the LLM learn from past successes and failures.

Let’s break these components down.

1. The Dual-Layer Self-Evolutionary Mechanism

Why two layers? Previous attempts like FunSearch or Evolution of Heuristics (EOH) mostly focused on evolving the code (the heuristic). The problem is that LLMs can get stuck in “local optima”—they keep generating variations of the same code structure even if it’s not working well.

The Outer Layer acts as a diversity manager. If the Inner Layer (the code generator) stagnates and stops improving, the Outer Layer detects this and evolves the prompt itself. It might switch the instruction from “Improve efficiency” to “Explore a completely different mathematical approach.”

This synergy allows the system to balance Exploitation (refining good code in the Inner Layer) and Exploration (trying new ideas via the Outer Layer).

2. Differential Memory for Directional Evolution

Standard evolutionary algorithms often rely on random crossover (combining two parents) and mutation. However, an LLM is smart—it doesn’t need to rely on randomness. It can reason.

The researchers introduced Differential Memory. Instead of just giving the LLM two parent algorithms and saying “combine these,” they provide the LLM with a history of good strategies and bad strategies along with their performance scores.

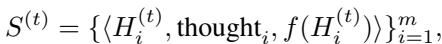

The system feeds the LLM a set of tuples \(S^{(t)}\) containing the code (\(H\)), the reasoning (“thought”), and the fitness score (\(f\)).

The LLM is then prompted to explicitly learn from the difference between high-performing and low-performing strategies. It asks the LLM to identify what made the good ones work and the bad ones fail, acting as an optimizer rather than just a text generator.

3. The Evolutionary Path

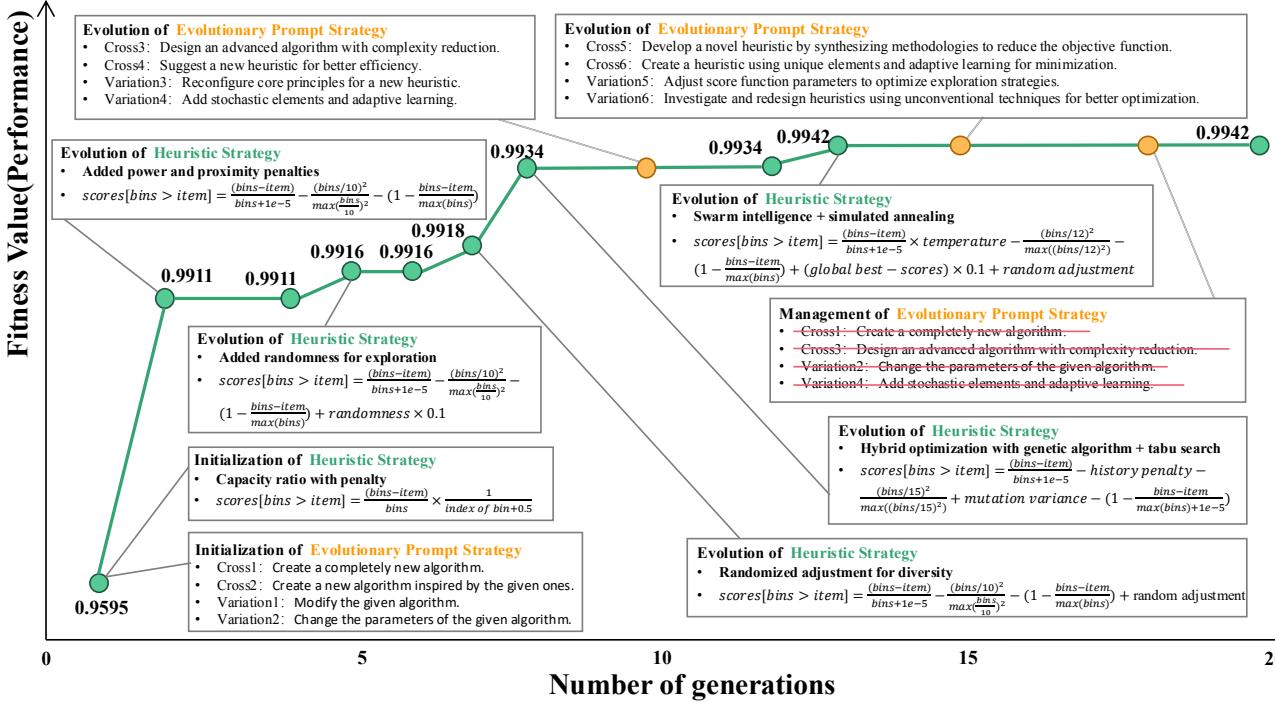

What does this look like in practice? The diagram below visualizes the “thoughts” of the agent over 20 generations of solving a Bin Packing problem.

Notice the trajectory:

- Generation 0: The agent starts with basic, intuitive logic (e.g., “Capacity Ratio Penalty”).

- Generation 5-8: It realizes it’s getting stuck, so it introduces “Randomness” and “Hybrid Optimization” (Genetic Algorithms + Tabu Search).

- Generation 12+: It evolves sophisticated “Swarm Intelligence” concepts.

The fitness value (the green line) climbs steadily. The key takeaway here is that the LLM invented these complex strategies (Simulated Annealing, Tabu Search) on its own to solve the specific problem at hand.

The diagram below shows the specific code and thought process evolution in more detail. You can see the code becoming more sophisticated as the “Prompts” evolve from simple instructions to complex directives about parameter settings.

Application: Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search (ALNS)

The code generated by the LLM isn’t solving the MILP directly; it is acting as a “Scoring Function” inside an Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search (ALNS) loop.

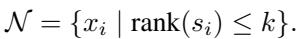

The generated Python function accepts the current state of the problem (variables, constraints) and outputs a score for each variable. The ALNS algorithm then picks the top \(k\) variables to “destroy” (free up for optimization).

By training on small-scale problems (thousands of variables), the LLM learns general rules about which variables are “important.” These rules then scale surprisingly well to massive problems (millions of variables) without retraining.

Experimental Results

The researchers validated LLM-LNS on two fronts: Combinatorial Optimization (standard puzzles) and Large-Scale MILP (industrial-style math problems).

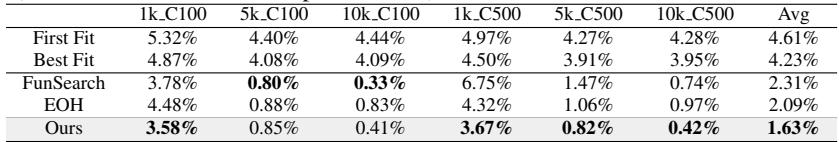

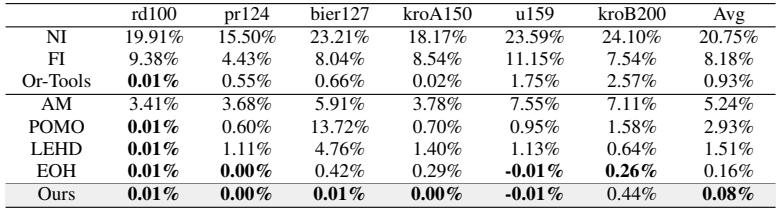

1. Combinatorial Optimization: Beating FunSearch

First, they tested the agent on the Online Bin Packing problem. They compared LLM-LNS against FunSearch (DeepMind’s Nature paper method) and EOH.

In Table 2 (above), lower numbers are better (fewer excess bins used). LLM-LNS achieves an average score of 1.63%, significantly outperforming FunSearch (2.31%) and EOH (2.09%). This proves the Dual-Layer agent is a better “algorithm designer” than previous LLM-based methods.

They observed similar dominance in the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), where LLM-LNS found heuristics that brought solutions closer to optimality than neural baselines like POMO or LEHD.

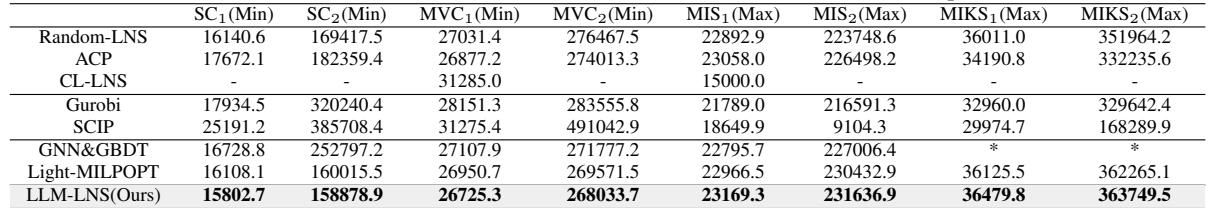

2. The Main Event: Large-Scale MILP

The ultimate test was applying this to MILP datasets: Set Covering (SC), Minimum Vertex Cover (MVC), Maximum Independent Set (MIS), and Knapsack (MIKS).

They trained the agent on small instances and tested it on massive instances with up to 2 million variables.

Table 4 presents the critical results. Here is what the columns represent:

- Gurobi/SCIP: The gold-standard commercial and open-source solvers.

- GNN&GBDT / Light-MILPOPT: Modern Machine Learning approaches using Graph Neural Networks.

- LLM-LNS (Ours): The proposed method.

The Result: LLM-LNS finds better solutions (lower for minimization, higher for maximization) than Gurobi and SCIP on almost every large-scale instance. Notably, on the massive SC2 (Set Covering) instance, LLM-LNS finds a solution with a cost of 158,878, while Gurobi gets stuck at 320,240. That is a massive efficiency gap.

Furthermore, traditional ML methods like GNN&GBDT failed to solve the Knapsack (MIKS) problems entirely (indicated by *), while LLM-LNS handled them robustly.

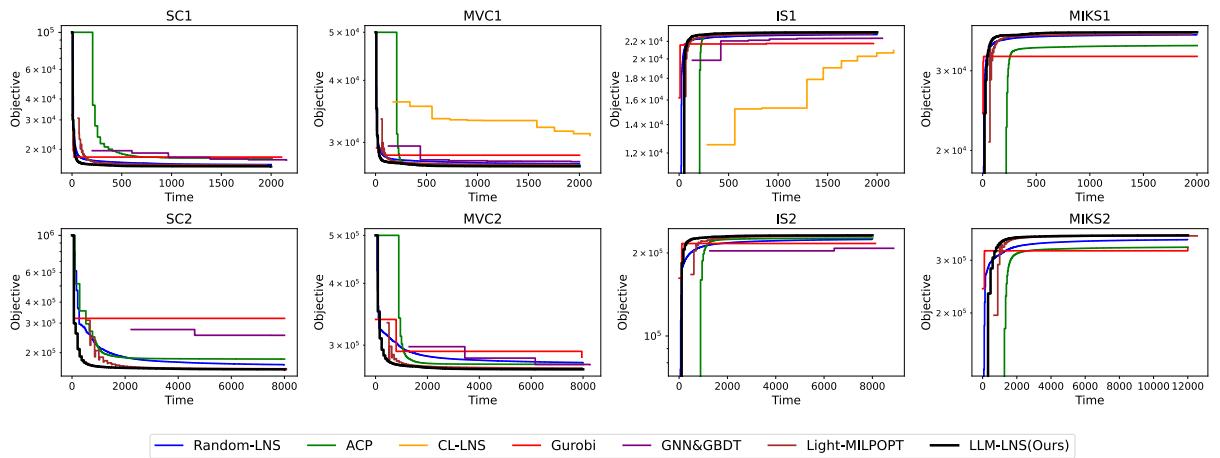

3. Convergence Speed

It’s not just about the final score; it’s about how fast you get there.

In Figure 3, the black line represents LLM-LNS. You can see it consistently drops (improves) faster than the other colored lines. In the SC2 and MVC2 plots, the difference is stark—the LLM-driven method finds high-quality solutions almost immediately, while traditional solvers struggle to make progress.

Why Does This Matter?

This research represents a paradigm shift in how we approach optimization.

- Overcoming the Cold Start: Traditional ML needs massive datasets of solved problems to “learn” a heuristic. LLM-LNS needs only a few small examples because the LLM already possesses general reasoning and coding capabilities.

- Scalability: Most neural networks trained on small graphs fail when applied to graphs 100x larger. LLM-LNS generates logic (code), not just weights. Logic like “prioritize variables with high coefficients” works regardless of whether you have 100 or 1,000,000 variables.

- Interpretability: Because the output is Python code, human experts can read the heuristic. You can look at the code generated in Generation 20 and understand why the algorithm is making its decisions.

Conclusion

LLM-LNS successfully demonstrates that Large Language Models can do more than just chat or summarize text; they can act as automated researchers. By wrapping an LLM in a dual-layer evolutionary framework with differential memory, the researchers created a system that designs optimization algorithms superior to those created by human experts or traditional deep learning.

As we move toward increasingly complex global systems—in energy grids, supply chains, and manufacturing—the ability to automatically design scalable, efficient algorithms will be a critical tool. LLM-LNS is a significant step in that direction.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/8491_large_language_model_driv-1758/images/cover.png)