Introduction

Imagine you have trained a massive Large Language Model (LLM). It is brilliant, articulate, and knowledgeable. Unfortunately, it also memorized the home address of a celebrity, or perhaps it learned a dangerous recipe for a chemical weapon, or it simply believes that Michael Jordan plays baseball (which was only true for a brief, confusing stint in the 90s).

You need to fix this. You need the model to “forget” the sensitive data or “edit” the wrong fact without destroying its ability to speak English or answer other questions.

This is the challenge of Knowledge Editing and Unlearning. Current techniques often try to pinpoint where a fact is stored and tweak the weights. However, a new paper titled “Mechanistic Unlearning: Robust Knowledge Unlearning and Editing via Mechanistic Localization” reveals a critical flaw in how we usually do this. Most existing methods act like putting a piece of tape over the model’s “mouth”—they target the output mechanism. If you rip the tape off (or prompt the model differently), the secret comes spilling out.

In this post, we will dive deep into this research. We will explore how the authors used Mechanistic Interpretability to distinguish between where a model fetches a fact and where it speaks it. By targeting the source—the “Fact Lookup” mechanism—they achieved unlearning that is far more robust, permanent, and safe.

Background: The Problem with “Output Tracing”

To understand the innovation of this paper, we first need to look at the status quo. When researchers want to edit a model (e.g., change “The Eiffel Tower is in Paris” to “The Eiffel Tower is in Rome”), they need to find which parameters to change.

The standard approach is Output Tracing (OT). Methods like Causal Tracing work by analyzing which components of the model, when corrupted or restored, have the biggest impact on the final probability of the output token (e.g., “Paris”).

The logic seems sound: if a specific layer strongly affects the output word “Paris,” that must be where the knowledge lives, right?

Not necessarily. The authors of this paper argue that OT methods often identify the Extraction Mechanism—the layers responsible for taking an internal concept and formatting it into the correct next word. They miss the Fact Lookup Mechanism—the earlier layers where the concept is actually retrieved from the model’s memory.

If you only edit the Extraction Mechanism, you haven’t removed the knowledge; you’ve just broken the link to the specific word output. The model still “knows” the fact in its latent space, and that knowledge can be coaxed out using different sentence structures or multiple-choice questions.

Core Method: Mechanistic Unlearning

The researchers propose a new paradigm: Mechanistic Unlearning. Instead of looking at what affects the output, they look at the internal mechanics of how the model processes information.

The Two Mechanisms: Lookup vs. Extraction

The paper builds on previous interpretability work identifying that Transformer models often process facts in two distinct stages:

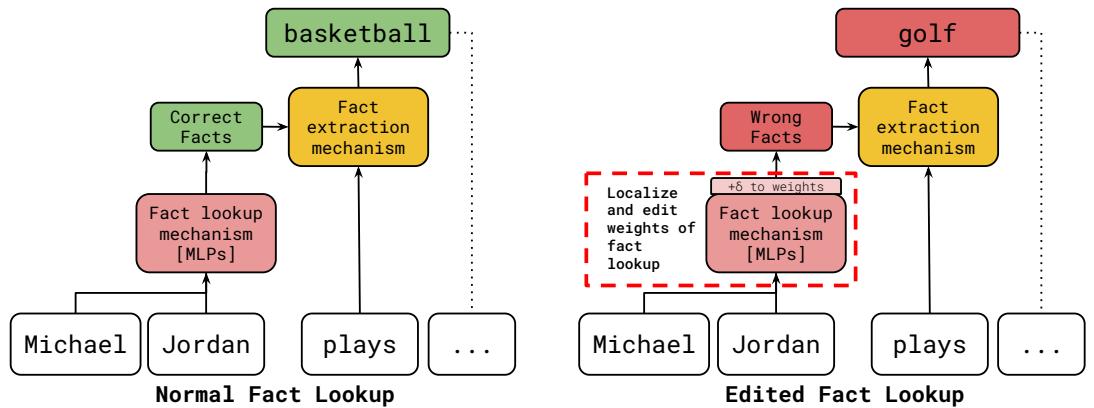

- Fact Lookup (FLU): This usually happens in the middle layers (specifically the Multi-Layer Perceptrons, or MLPs). The model sees the subject (e.g., “Michael Jordan”) and enriches the internal data stream with attributes (e.g., “Basketball”).

- Fact Extraction: This happens in the later layers. Attention heads and MLPs read that enriched data stream and decide which word to predict next.

The authors’ hypothesis is simple but powerful: To robustly edit a fact, you must target the Lookup mechanism, not the Extraction mechanism.

As shown in Figure 1 above, Mechanistic Unlearning focuses on localizing and editing the weights in the “Fact Lookup” box. By changing the association before it reaches the extraction phase, the edit becomes fundamental to the model’s internal reality, regardless of how the question is phrased.

How Do They Find the “Lookup” Layers?

Finding these specific components requires different techniques for different types of data. The authors focused on two datasets: Sports Facts (relational data) and CounterFact (general knowledge).

1. Probing for Sports Facts

For the Sports dataset, the authors used linear probes. A probe is a small classifier trained on the internal activations of the model at each layer. They trained these probes to predict the sport of an athlete (e.g., knowing the input is “Tiger Woods,” can the probe predict “Golf” from layer 5’s data?).

They found a specific range of MLP layers where the probe’s accuracy skyrocketed. This indicated that the “concept” of the sport was being retrieved and added to the residual stream at exactly those layers. This is the FLU Localization.

2. Path Patching for CounterFact

For general facts, probes are harder to use because the answers aren’t limited to a small set of categories (like sports). Instead, the authors used Path Patching.

They traced the flow of information backwards. First, they found the “Extraction” heads—the components in the final layers that directly affected the output logits. Then, they looked for earlier MLP layers that had a strong direct effect on those Extraction heads. This allowed them to identify the MLPs that were feeding information to the output mechanism.

The Editing Process

Once the specific MLPs responsible for Fact Lookup were identified (the Localization step), the authors applied Localized Fine-Tuning.

They updated the weights of only those identified components using a loss function designed to:

- Inject the new/forgotten fact (minimize loss on the target).

- Retain general knowledge (ensure other facts aren’t damaged).

- Maintain fluency (keep the model speaking English correctly).

Experiments & Results

The researchers tested their Mechanistic Unlearning approach against standard baselines (like Causal Tracing and non-localized fine-tuning) on models like Gemma-7B, Gemma-2-9B, and Llama-3-8B.

The results highlight a stark difference in Robustness.

1. The Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) Test

One of the easiest ways to break a standard model edit is to change the format of the prompt. If you edit a model to believe the Eiffel Tower is in Rome using the prompt “The Eiffel Tower is in…”, the model might say “Rome.” But if you ask a multiple-choice question: “Where is the Eiffel Tower? A) Paris B) Rome,” a poorly edited model will often revert to the original truth (“Paris”).

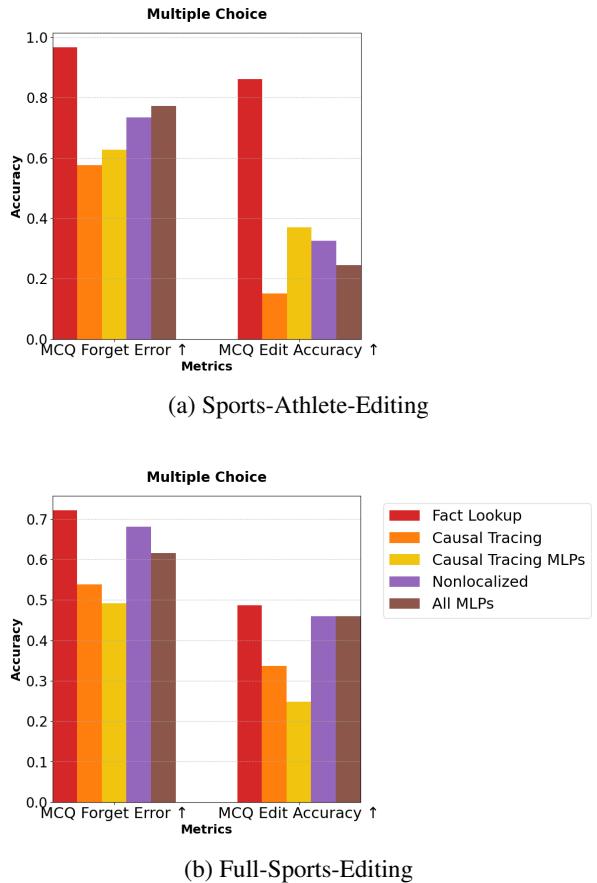

The authors tested this extensively. They looked at MCQ Forget Error (how often the model “accidently” remembers the old fact) and MCQ Edit Accuracy (how often it consistently chooses the new fact).

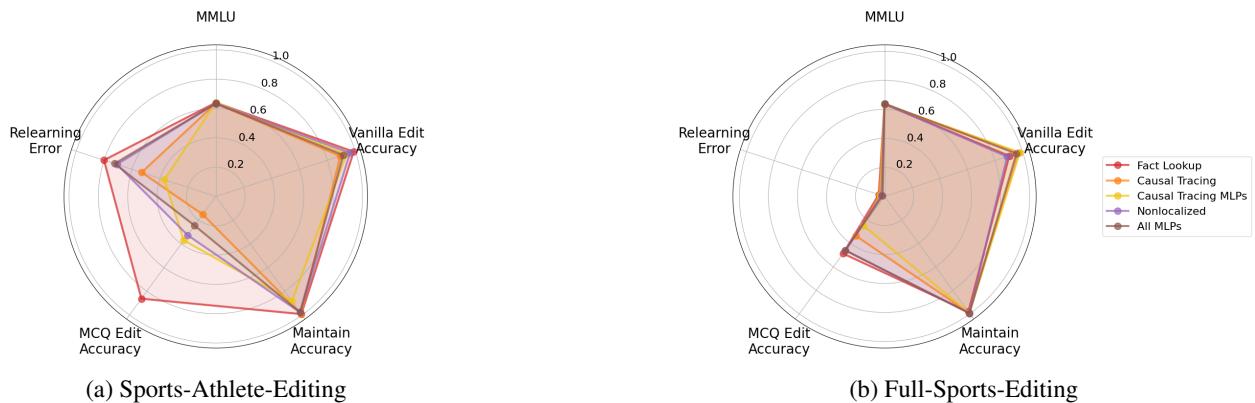

The spider plots in Figure 2 (above) tell a compelling story. Notice the “MCQ Edit Accuracy” axis. The Fact Lookup (FLU) method (in red) scores significantly higher than Causal Tracing (in orange) or Nonlocalized methods (purple). This suggests that FLU edits have genuinely altered the model’s knowledge, whereas OT methods have merely overfit to the specific training prompt sentence structure.

We can see this even more clearly in the bar charts below.

In Figure 3(a), look at the MCQ Edit Accuracy on the right side. The red bar (FLU) is towering over the others. Standard Output Tracing (orange) performs abysmally here, barely better than random chance in some cases. This confirms that Output Tracing edits are “brittle”—they shatter when the prompt format changes.

2. Adversarial Relearning

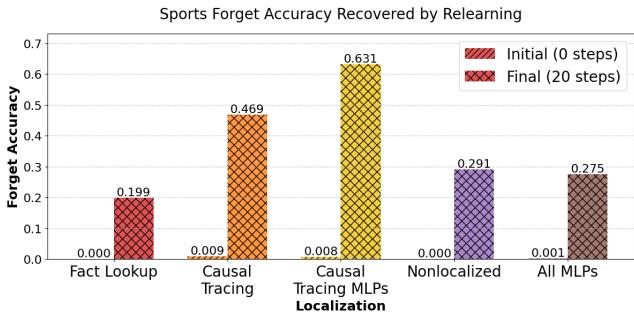

Another rigorous test of unlearning is Relearning. If you delete a file from your computer but don’t empty the trash, it’s easy to restore. Similarly, if an unlearning method just suppresses a fact, re-training the model on just a tiny bit of related data might bring the original memory rushing back.

The researchers split their “forget sets” in half. They edited the model to forget the facts, and then lightly re-trained the model on the first half of the original true facts. Then, they tested if the model “remembered” the second half.

Figure 6 is perhaps the most damning evidence against current methods.

- Initial state (Red striped bars): Most methods successfully suppress the fact initially.

- After Relearning (Orange cross-hatch): Look at Causal Tracing. The accuracy shoots back up to over 60%. The model didn’t forget; it was just hiding the information, and a tiny bit of training brought it back.

- Fact Lookup (Leftmost): The accuracy stays near zero. The model genuinely cannot retrieve the information because the internal mechanism for that fact has been scrambled.

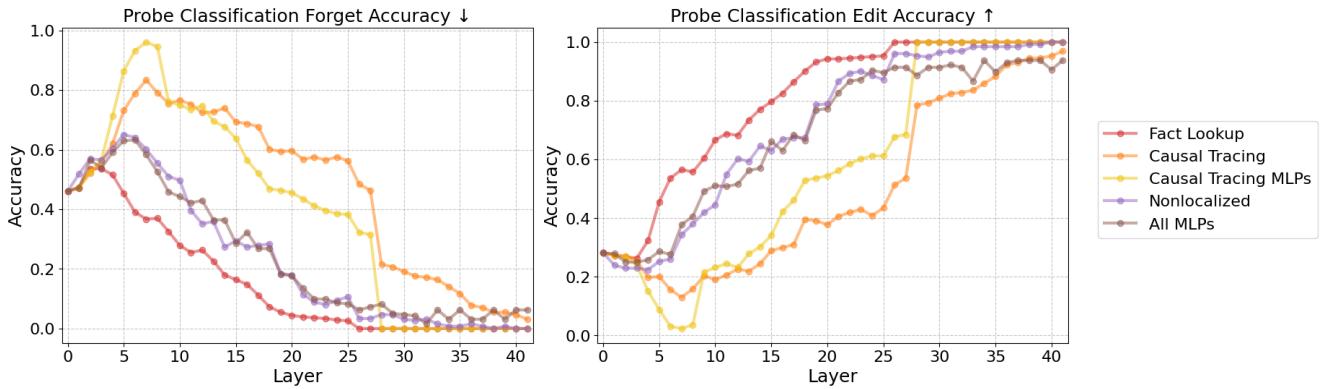

3. Investigating the Latent Space

To verify why this was happening, the authors peered inside the model’s “brain” using linear probes again. They wanted to see: is the original fact still floating around in the hidden layers, even if the output is different?

Figure 40 (Left) reveals the internal state. The Y-axis represents how accurately a probe can decode the original (forgotten) fact from the model’s activations.

- Orange Line (Causal Tracing): Notice how high it stays in the early/middle layers (0 to 15). The model still knows the truth internally. The edit only suppresses it at the very end.

- Red Line (Fact Lookup): The line drops and stays low. The internal representation of the old fact has been wiped out.

This confirms the “Tape over the mouth” analogy. Causal Tracing leaves the internal thought intact; Mechanistic Unlearning removes the thought itself.

Discussion & Implications

This paper makes a significant contribution to AI safety and utility. As models become more integrated into society, the ability to selectively and robustly edit them is non-negotiable.

Why Localization Matters

The key takeaway here is that not all parameters are created equal. You can achieve the same “test accuracy” on a specific prompt by editing different parts of the model, but the generalization of that edit depends entirely on where you make the change.

- Extraction Editing (OT): Changes the translation of thought-to-word. Good for superficial changes, bad for deep knowledge removal.

- Lookup Editing (FLU): Changes the retrieval of the concept. Necessary for true unlearning.

Parameter Efficiency

Interestingly, the authors also found that Mechanistic Unlearning is efficient. By targeting the FLU mechanism, they modified fewer parameters to achieve better results compared to editing the whole model or random layers.

The Threat of Latent Knowledge

The findings regarding Latent Knowledge (Figure 40) are particularly relevant for safety. If a model is “unlearned” of hazardous knowledge using Output Tracing, the hazard is still inside the weights. A malicious actor with access to the weights (or using fine-tuning API access) could easily surface that latent knowledge. Mechanistic Unlearning provides a much stronger defense against such attacks.

Conclusion

The paper “Mechanistic Unlearning” teaches us that to fix a language model, we have to think like a neurosurgeon, not a makeup artist. We cannot simply paint over the output; we must locate the specific neural circuits where memories are retrieved and operate there.

By distinguishing between Fact Lookup and Fact Extraction, the authors demonstrated that we can perform edits that are robust to rephrasing, resistant to relearning, and effective at scrubbing the internal latent state of the model.

As we continue to scale LLMs, techniques like this—which leverage Mechanistic Interpretability to guide model engineering—will be essential for creating AI that is not just knowledgeable, but also controllable and safe.

This blog post explains the research paper “Mechanistic Unlearning: Robust Knowledge Unlearning and Editing via Mechanistic Localization” by Guo et al. (2025).

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/9408_mechanistic_unlearning_ro-1600/images/cover.png)