Introduction

Imagine you have trained a state-of-the-art AI model to classify text. It works perfectly on your test data. Then, a malicious actor changes a single word in an input sentence—swapping “bad” with “not good”—and suddenly, your model’s prediction flips completely. This is an adversarial attack, and it is one of the biggest vulnerabilities in modern Natural Language Processing (NLP).

To fix this, researchers typically use Adversarial Training (AT), where they force the model to learn from these tricky examples during training. However, this comes with a heavy price:

- Computational Cost: You often have to retrain the entire massive model (like BERT or RoBERTa) from scratch.

- Performance Degradation: The model gets so focused on spotting tricks that it becomes worse at understanding normal, clean text (a phenomenon often called “catastrophic forgetting”).

- Rigidity: If a new type of attack is discovered tomorrow, you have to start the training process all over again.

What if there was a way to make models robust against attacks without retraining the whole network and without sacrificing performance on clean data?

Enter ADPMIXUP, a novel framework proposed by researchers at Indiana University Bloomington. This approach combines the efficiency of Adapters (tiny, plug-in modules for AI) with the mathematical power of Mixup (a data augmentation technique). The result is a system that can dynamically adjust its defense mechanism in real-time for every single input it receives.

In this post, we will deconstruct how ADPMIXUP works, why it is a game-changer for efficient AI defense, and how it manages to handle attacks it has never even seen before.

Background: The Building Blocks

To understand ADPMIXUP, we need to briefly look at three foundational concepts: Adapters, Adversarial Training, and Mixup.

1. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) via Adapters

Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) are huge. Fine-tuning them for specific tasks usually involves updating all their billions of parameters. Adapters offer a smarter alternative. Instead of updating the whole model, we freeze the pre-trained model and inject small, trainable layers (adapters) between the existing layers.

This reduces the number of parameters you need to train to as little as 0.1% of the original count. You can think of adapters as “skills” you plug into a frozen brain. You can have a “clean adapter” for normal reading and an “adversarial adapter” specialized in spotting tricks.

2. Adversarial Training

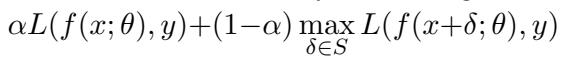

The standard formula for adversarial training looks like this:

Here, the model tries to minimize error on both the clean example (\(x\)) and an adversarial version (\(x + \delta\)). While effective, this creates a tug-of-war. The parameters that make the model good at clean data might conflict with the parameters needed for robust defense.

3. Mixup Data Augmentation

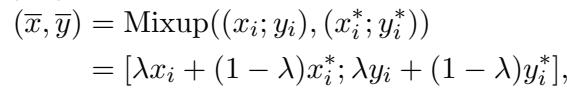

Mixup is a technique originally designed for images. It trains a model on “virtual” examples created by blending two images and their labels together.

If \(\lambda\) is 1, you have a clean image. If \(\lambda\) is 0, you might have an adversarial one. Mixup smooths out the decision boundaries of a model, making it less brittle. However, applying Mixup to text is hard. You can blend pixels, but blending the words “cat” and “dog” results in nonsense that doesn’t help the model learn grammar or syntax.

The Motivation: From Data Mixup to Model Mixup

The researchers realized that while mixing text data is messy, mixing model weights is mathematically elegant—provided the models are similar enough.

This concept is related to Model Soup, where weights of multiple fine-tuned models are averaged to improve performance.

However, if you try to average two completely different large language models, it fails because their optimization paths are too different. This is where Adapters save the day. Because adapters are small and trained on top of the same frozen pre-trained model, they stay close to each other in the parameter space.

This leads to the core insight of the paper: Instead of mixing the training data, we can train separate adapters (one clean, one adversarial) and mix their weights dynamically during inference.

The Core Method: ADPMIXUP

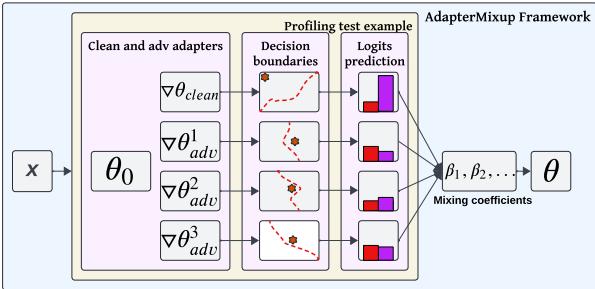

ADPMIXUP works by fine-tuning a PLM with multiple adapters: one trained on clean data and one (or more) trained on known adversarial attacks. During testing (inference), the system intelligently mixes these adapters to produce a final prediction.

The Architecture

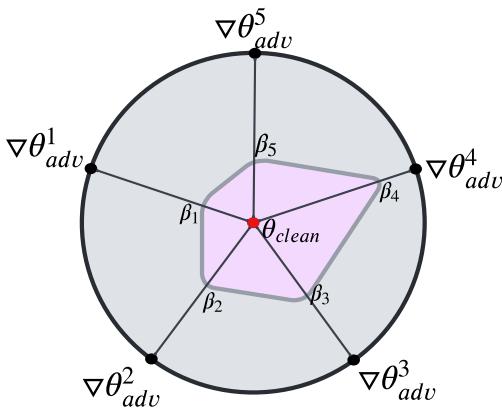

As shown in Figure 1, the process is dynamic:

- The input \(x\) is processed.

- It passes through both the Clean Adapter and the Adversarial Adapter(s).

- The framework calculates mixing coefficients (\(\beta_1, \beta_2, \dots\)).

- These coefficients determine how much influence each adapter has on the final decision boundary (represented by the dashed red lines).

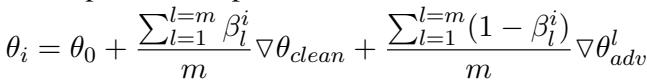

The Mathematical Formulation

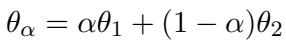

The mixing happens at the weight level. If we have a clean adapter (\(\nabla \theta_{clean}\)) and an adversarial adapter (\(\nabla \theta_{adv}\)), the final model parameters for a specific input are:

Here, \(\beta\) is the “mixing coefficient.”

- If \(\beta = 1\), the model uses only the Clean Adapter.

- If \(\beta = 0\), the model uses only the Adversarial Adapter.

- Ideally, we want something in between that captures the best of both worlds.

The “Smart” Switch: Dynamic \(\beta\) via Entropy

The brilliance of ADPMIXUP is that \(\beta\) is not a fixed number. It changes for every single sentence the model reads. But how does the model know if an incoming sentence is clean or an attack?

The authors use Entropy as a measure of uncertainty.

When a model trained only on clean data sees an adversarial attack, it gets confused. Its prediction probability distribution flattens out (it’s unsure which class is correct), causing the entropy to spike.

- Low Entropy: The model is confident. The input is likely clean. \(\beta\) should be high (closer to 1).

- High Entropy: The model is confused. The input is likely an attack. \(\beta\) should be low (closer to 0), activating the adversarial adapter.

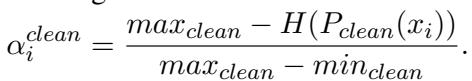

The system calculates a specific weight for the clean adapter (\(\alpha^{clean}\)) based on how the current entropy compares to the maximum and minimum entropy seen during training:

It performs a similar calculation for the adversarial adapter and averages them to find the final \(\beta\). This allows ADPMIXUP to profile the input and land in a “robust region” of weights, visualized below as the pink area:

Handling Multiple Attacks (\(m > 1\))

In the real world, attackers use many different strategies (e.g., misspellings, synonym swaps). ADPMIXUP can combine a clean adapter with multiple adversarial adapters simultaneously.

This equation shows that the final model is an average of the clean adapter and all available adversarial adapters, weighted by their respective dynamic \(\beta\) coefficients. This makes the system modular—you can simply “plug in” a new adapter for a new type of attack without retraining the others.

Experiments and Results

The researchers evaluated ADPMIXUP on the GLUE benchmark using BERT and RoBERTa models against various attack methods like TextFooler (word-level) and DeepWordBug (character-level).

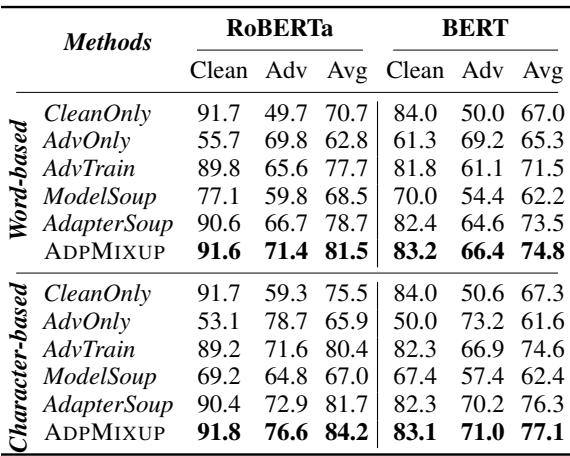

1. Superior Trade-offs

The primary goal was to find a balance between clean accuracy and adversarial robustness.

Table 2 highlights the results.

- CleanOnly: Great on clean data (91.7%), terrible on attacks (49.7%).

- AdvTrain (Standard Adversarial Training): Good on attacks, but drops clean accuracy (89.8%).

- ADPMIXUP: Maintains near-perfect clean accuracy (91.6%) while achieving superior adversarial robustness (71.4%). It achieves the highest Average score (81.5%), beating both Model Soup and Adapter Soup baselines.

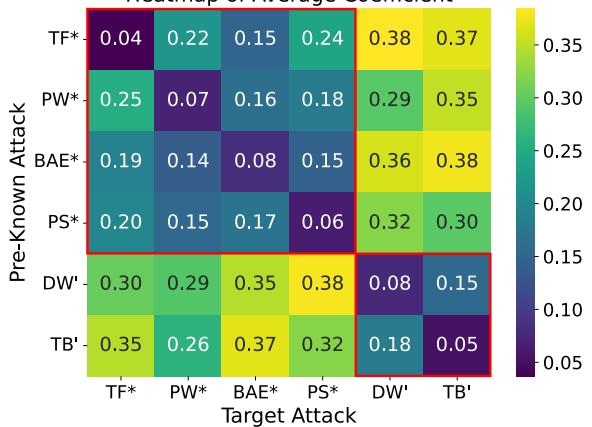

2. Generalization to Unknown Attacks

One of the hardest challenges is defending against attacks the model hasn’t seen. The researchers trained the model on one type of attack and tested it on others.

Figure 3 is a heatmap of the mixing coefficient \(\beta\).

- The x-axis represents the target (unknown) attack.

- The y-axis represents the pre-known attack adapter.

- The colors show that the model successfully “profiles” the attacks. When hit with a word-based attack (like TextFooler), the model automatically assigns higher weight to word-based adversarial adapters (darker colors/lower \(\beta\)), even if it’s a different specific algorithm. This proves ADPMIXUP can transfer knowledge to defend against unknown threats.

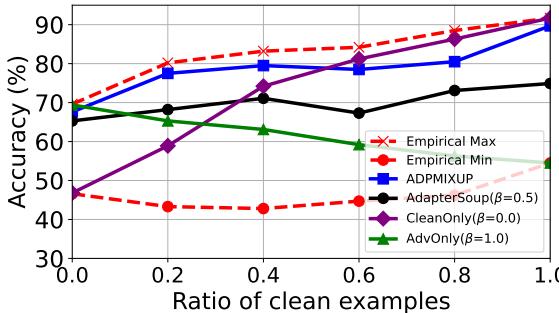

3. Empirical Optimality

How close is the dynamic \(\beta\) to the theoretically perfect mix?

Figure 4 compares ADPMIXUP (blue line) against the “Empirical Max” (red star)—the best possible result if you manually picked the perfect \(\beta\) for every batch. ADPMIXUP tracks the optimal performance very closely, far outperforming static mixing strategies (like AdapterSoup with fixed weights).

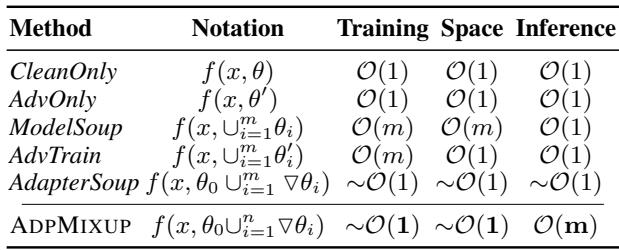

4. Efficiency and Complexity

Finally, is it fast?

Table 7 shows that training complexity is essentially \(O(1)\) regarding the full model size because we only train tiny adapters.

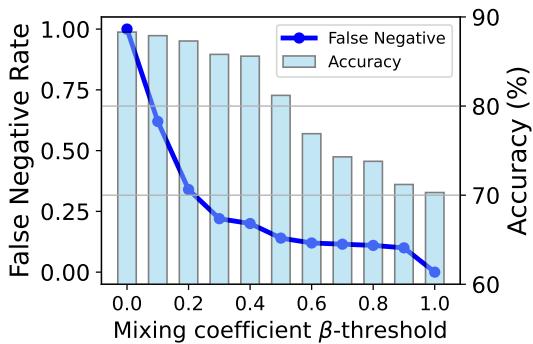

During inference, calculating \(\beta\) does require running the adapters, which is nominally \(O(m)\) for \(m\) attacks. However, because we can detect clean inputs quickly using the entropy threshold, we don’t always need to activate the adversarial adapters.

Figure 5 demonstrates that by setting a threshold on \(\beta\) (e.g., 0.4), the system creates a “short-circuit.” If the input looks clean (high \(\beta\)), the system skips the heavy adversarial calculations. This brings the runtime complexity down significantly, making it practical for real-world deployment.

Conclusion and Implications

ADPMIXUP offers a compelling solution to the “robustness vs. efficiency” dilemma in AI. By shifting the concept of “Mixup” from data augmentation to model weight augmentation, and leveraging the modularity of Adapters, the authors have created a framework that is:

- Modular: New defenses can be added as new adapters without retraining the base model.

- Efficient: It requires a fraction of the parameters of full adversarial training.

- Smart: It uses entropy to dynamically profile inputs, ensuring clean data is treated normally while attacks are met with robust defenses.

- Interpretable: The mixing coefficients provide insight into what kind of attack the model thinks it is facing.

As Large Language Models (LLMs) continue to be integrated into critical systems (finance, healthcare, security), the ability to patch vulnerabilities quickly and efficiently—without degrading general performance—is vital. ADPMIXUP paves the way for a future where AI models are not just knowledgeable, but also adaptable and secure.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2714/images/cover.png)