When you ask a professor a simple question like “What is 2 + 2?”, you expect a simple answer: “4.” But if you ask, “How does a neural network learn?”, you expect a detailed, step-by-step explanation.

If the professor gave a twenty-minute lecture on number theory just to answer “2 + 2,” you’d be confused. Conversely, if they answered the deep learning question with a single word, you’d learn nothing.

Large Language Models (LLMs) suffer from this exact problem. Current prompting techniques, like Chain-of-Thought (CoT), tend to apply a “one-size-fits-all” approach. They either force the model to be too simple for hard problems or too complex for easy ones.

In this post, we will dive into a fascinating paper titled “Adaptation-of-Thought: Learning Question Difficulty Improves Large Language Models for Reasoning.” The researchers propose a new method, ADoT, that teaches LLMs to assess how hard a question is and adapt their reasoning process accordingly.

The “Goldilocks” Problem in Reasoning

To get the best performance out of LLMs for reasoning tasks (like math word problems or commonsense logic), researchers use prompting. A popular method is “Few-Shot Chain-of-Thought,” where you give the model a few examples (demonstrations) of questions and their step-by-step solutions before asking your target question.

However, there is a mismatch problem.

- Simple Prompts: If the examples in your prompt are too simple, the LLM won’t trigger the deep reasoning needed to solve complex calculus or logic puzzles.

- Complex Prompts: If the examples are incredibly detailed and complex (like those used in methods called PHP or Complex-CoT), the LLM might over-think simple questions. It might hallucinate steps that don’t exist or get lost in its own verbosity.

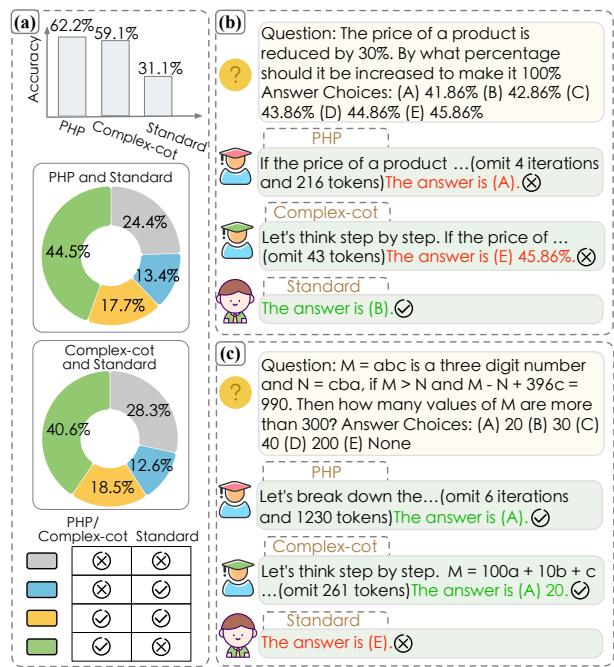

The researchers analyzed this phenomenon on the AQUA dataset (algebra questions). Look at the breakdown below:

In Figure 1 (a), you can see that while complex methods (like PHP) generally perform well, there is a slice of the pie (13.4% and 12.6%) where the Standard (simple) method gets the answer right, but the complex methods fail.

Figure 1 (b) shows why: For a simple percentage question, the complex models (PHP and Complex-CoT) over-analyze and get it wrong. The Standard model just answers it. Conversely, in Figure 1 (c), the hard question stumps the Standard model because it doesn’t reason enough, while the complex models succeed.

We need a method that adapts. We need Adaptation-of-Thought (ADoT).

The Solution: Adaptation-of-Thought (ADoT)

The core idea of ADoT is to dynamically adjust the complexity of the prompt to match the difficulty of the question.

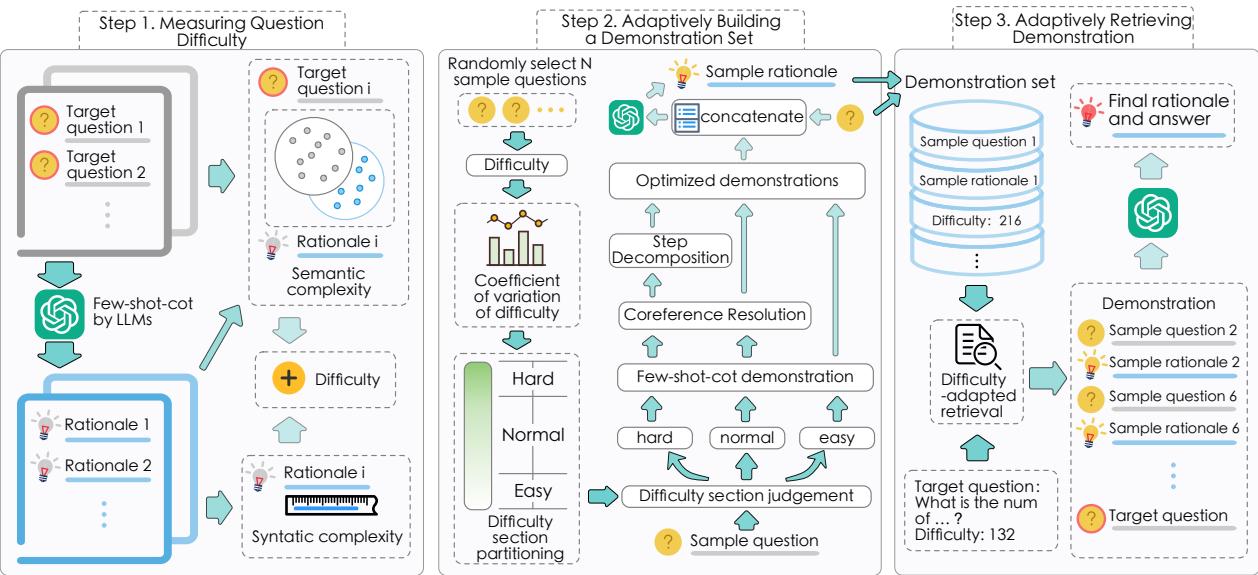

The method follows a three-stage pipeline:

- Measure the difficulty of the question.

- Construct a library of demonstrations with varying difficulty levels.

- Retrieve the specific demonstrations that match the difficulty of the current question.

Here is the high-level architecture of the system:

Let’s break down each of these three steps to understand the mechanics.

Step 1: Measuring Question Difficulty

How do you scientifically measure how “hard” a question is? The authors argue that difficulty isn’t just about the question text; it’s about the rationale (the reasoning path) required to solve it.

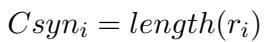

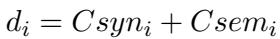

They quantify difficulty using two metrics: Syntactic Complexity and Semantic Complexity.

1. Syntactic Complexity This measures the sophistication of the form. Generally, a longer chain of reasoning indicates a harder problem. They measure this simply by the length of the rationale (\(r_i\)):

2. Semantic Complexity This measures the knowledge gap. A question is “hard” if the solution requires introducing a lot of external knowledge or concepts that weren’t present in the question itself. They calculate this by counting the number of non-repetitive “semantic words” (nouns, verbs, etc.) in the rationale that did not appear in the question (\(q_i\)):

3. Comprehensive Difficulty The total difficulty score (\(d_i\)) is the sum of these two metrics. This gives the system a single number representing how much effort is required to solve the problem.

Step 2: Adaptively Building a Demonstration Set

Now that the system knows how to measure difficulty, it needs a library of examples to show the LLM. You can’t just use random examples; you need high-quality examples that range from “Easy” to “Hard.”

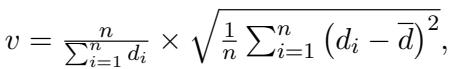

The researchers take a set of sample questions and categorize them based on the difficulty scores calculated in Step 1. To decide the thresholds for Easy, Normal, and Hard, they use the coefficient of variation (\(v\)) to see how spread out the difficulty scores are:

Based on this distribution, they split the questions into three buckets. But they don’t stop there. They optimize the text of the solutions to make them better teaching tools for the LLM.

- For “Easy” questions: They keep the standard Chain-of-Thought demonstrations.

- For “Normal” questions: They apply Coreference Resolution. This replaces pronouns (he, she, it) with the actual nouns they refer to. This reduces ambiguity, making it easier for the LLM to follow the logic.

- For “Hard” questions: They apply both Coreference Resolution and Step Decomposition.

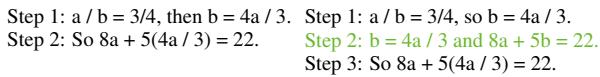

What is Step Decomposition? Hard questions often have “leaps” in logic that confuse models. Step decomposition breaks a single complex reasoning step into smaller, explicit bridges.

As shown in Table 1, adding an intermediate step (calculating \(b\) explicitly before substituting it) makes the logic undeniable. By feeding the LLM these “super-clear” hard examples, the model learns to be meticulous when facing difficult problems.

Step 3: Adaptively Retrieving Demonstrations

We now have a difficulty score for our target question and a library of optimized examples (Easy, Normal, Hard). The final piece of the puzzle is the retrieval mechanism.

When a new question comes in, the system predicts its difficulty. It then retrieves \(M\) demonstrations from the library that have the closest difficulty score to the target question.

If the question is hard, the prompt is filled with examples of complex, step-decomposed reasoning. If the question is easy, the prompt contains concise, direct reasoning. This solves the mismatch problem identified in the introduction.

Experimental Results

Does ADoT actually work? The researchers tested it against 13 baselines (including Zero-Shot, Auto-CoT, and PHP) across 10 datasets covering Arithmetic, Symbolic, and Commonsense reasoning.

Performance Across Difficulty Levels

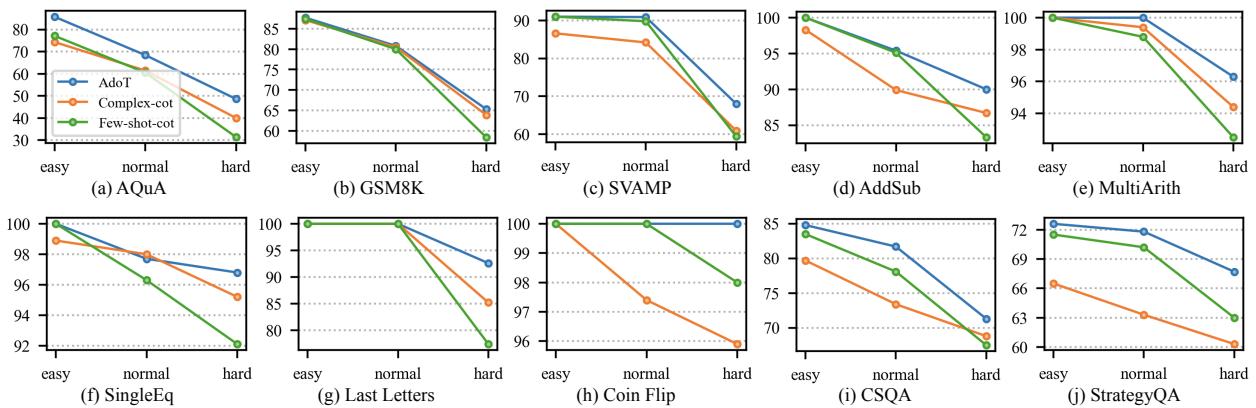

The most telling result is how ADoT performs across different difficulty sections compared to the baselines.

In Figure 3, look at the blue line (ADoT).

- Easy questions: ADoT performs nearly as well as or better than the simple method (Few-shot-cot, green line), avoiding the “overthinking” trap.

- Hard questions: ADoT matches or beats the complex method (Complex-cot, orange line), providing the necessary depth.

- Consistency: Unlike the baselines, which fluctuate wildly depending on difficulty, ADoT is stable.

The Importance of Adaptive Retrieval

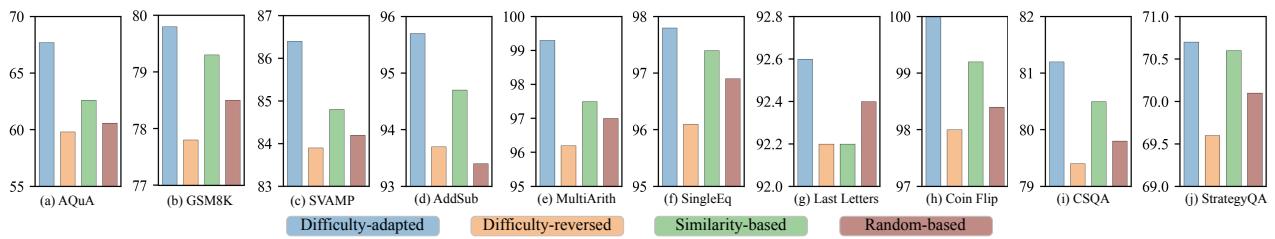

Critics might ask: “Does matching difficulty really matter? What if we just picked random examples?” The authors tested this by comparing their Difficulty-adapted method against a Difficulty-reversed method (giving easy examples for hard questions and vice versa) and a Random method.

The results in Figure 4 are stark. The blue bars (Difficulty-adapted) are consistently the highest. The orange bars (Difficulty-reversed) are often the lowest. This empirically proves that the mismatch between question difficulty and prompt complexity is a major cause of errors in LLM reasoning.

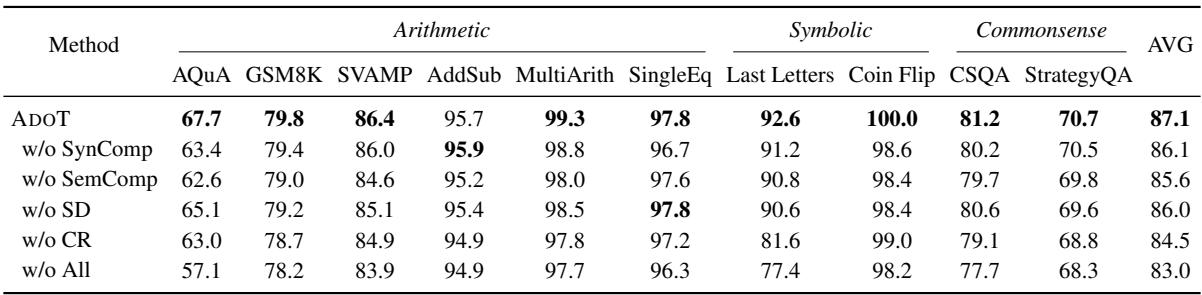

Ablation Study: What Components Matter?

The researchers also stripped the model down to see which parts were driving the success.

- w/o SynComp / SemComp: Removing either the syntactic or semantic complexity measures dropped performance. Interestingly, removing Semantic Complexity (knowledge) hurt more than Syntactic (length), suggesting that what the model knows is slightly more important than how much it writes.

- w/o SD / CR: Removing Step Decomposition (SD) and Coreference Resolution (CR) also hurt performance. This validates that optimizing the quality of the examples (not just selecting them) is crucial.

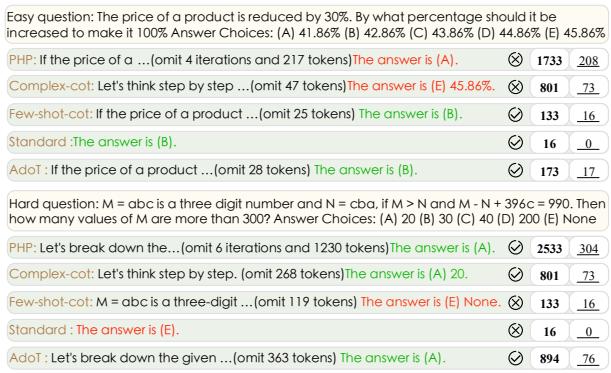

Case Study: Seeing is Believing

Finally, let’s look at the actual text output to see how ADoT behaves compared to other methods.

In Figure 6:

- Easy Question (Top): The complex model (PHP) tries to iterate 4 times and writes 208 tokens, eventually getting the wrong answer (A). The Standard model answers correctly (B) with just 16 tokens. ADoT correctly identifies it as an easy question, uses a short reasoning path (17 tokens), and gets it right (B).

- Hard Question (Bottom): The Standard model barely tries (0 reasoning tokens) and fails. The complex model (PHP) writes a massive wall of text (304 tokens) and gets it right. ADoT identifies it as hard, generates a detailed rationale (76 tokens), and also gets the correct answer (A).

Conclusion

The “Adaptation-of-Thought” paper highlights a maturity in LLM research. We are moving away from trying to find the “one magical prompt” that solves everything, and toward adaptive systems that treat different inputs differently.

By quantifying difficulty through syntactic and semantic complexity, and dynamically adjusting the examples provided to the model, ADoT achieves state-of-the-art results. It reminds us that in AI, just like in teaching, the best explanation is the one that fits the student—and the problem—perfectly.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2715/images/cover.png)