Breaking Boundaries: How to Segment Sentences in Messy Clinical Data

If you have ever tried to process text data for a Natural Language Processing (NLP) project, you know that the very first step is often the most deceptive. Before you can perform sentiment analysis, name entity recognition (NER), or machine translation, you have to answer a simple question: Where does one sentence end and the next one begin?

In formal writing—like a novel or a news article—this is trivial. You look for a period, a question mark, or an exclamation point, and you split the text. But what happens when the text is written by a doctor rushing between patients? What if the text is a stream of consciousness, a list of vital signs, or a fragmented note like “pt sedated no response to verbal stimuli”?

In this post, we are going to dive deep into a research paper titled “Automatic sentence segmentation of clinical record narratives in real-world data.” We will explore why traditional tools fail miserably on clinical text, and we will break down a novel solution that uses deep learning and a clever sliding window algorithm to solve the problem—without relying on punctuation.

The Invisible Problem: Why Segmentation Matters

Sentence segmentation is the foundational layer of the NLP pyramid. Almost every sophisticated model downstream expects a coherent sentence as input.

Imagine an English-to-Spanish translation model. If you feed it two half-sentences mashed together, the translation will be nonsense. Similarly, in clinical NLP, if we want to extract a diagnosis or a medication list, the system needs to know the boundaries of the thought. Errors here propagate upwards. If a segmenter fails, it can ruin the performance of coreference resolution (figuring out who “he” refers to) or summarization tasks.

The “Period” Fallacy

For decades, the standard approach to this problem was rule-based. We assumed that a sentence is a grammatical sequence of words ending in a specific punctuation mark (PM), usually . ? or !.

Standard tools like the Stanford CoreNLP or the NLTK tokenizer rely heavily on these rules. They might use regular expressions or simple machine learning classifiers to decide if a period is a full stop or part of an abbreviation (like “Dr.” or “U.S.”).

This works beautifully for the Wall Street Journal. It fails catastrophically for Electronic Health Records (EHRs).

Clinical notes are “real-world” data. They are characterized by:

- Fragmentation: Incomplete sentences (“No fever.”).

- Missing Punctuation: Thoughts are separated by newlines or just spaces rather than periods.

- Complex Layouts: Headers, bullet points, and tables that don’t follow standard grammar.

If a doctor types “BP 120/80 HR 70”, a standard rule-based system might see one sentence. But semantically, these are two distinct measurements that might need to be processed separately.

The Approach: Sequence Labeling Over Rules

The researchers proposing this new method decided to abandon the idea of looking for “Sentence Ending Punctuation Marks” (EPMs). Instead, they reframed the problem. They stopped asking, “Is this character a period?” and started asking, “Is this word the beginning of a new sentence?”

They treat sentence segmentation as a Sequence Labeling Task.

The BIO Tagging Scheme

To train a model to recognize sentences without punctuation, the authors utilize a BIO tagging scheme. This is a common technique in Named Entity Recognition, but here it is applied to sentence boundaries.

For every token (word) in a document, the model assigns one of three tags:

- B (Beginning): This token is the first word of a sentence.

- I (Inside): This token is inside a sentence (but not the start).

- O (Outside): This token is not part of a sentence (useful for ignoring metadata, markup, or headers).

By looking at the context of the words rather than just the punctuation, a deep learning model (specifically BERT) can learn that “HR” following a blood pressure reading usually signifies the Bginning of a new thought, even if there is no period between them.

The Core Innovation: The Sliding Window Algorithm

Using BERT for this task introduces a significant engineering challenge. BERT-based models have a strict input limit, typically 512 tokens.

Clinical notes can be extremely long—discharge summaries often run for thousands of words. You cannot simply squash an entire document into BERT.

Why Simple Splitting Fails

The naive solution is to chop the document into 512-token chunks, process them, and glue them back together. But what happens if the cut point (the 512th token) lands right in the middle of a sentence? The model loses the context for the second half of that sentence, leading to bad predictions at the boundaries.

The Dynamic Sliding Window

The researchers proposed a dynamic sliding window algorithm that adjusts based on what the model predicts. This allows them to process documents of infinite length “on the fly” while ensuring the model always has enough context.

Let’s look at how this works conceptually:

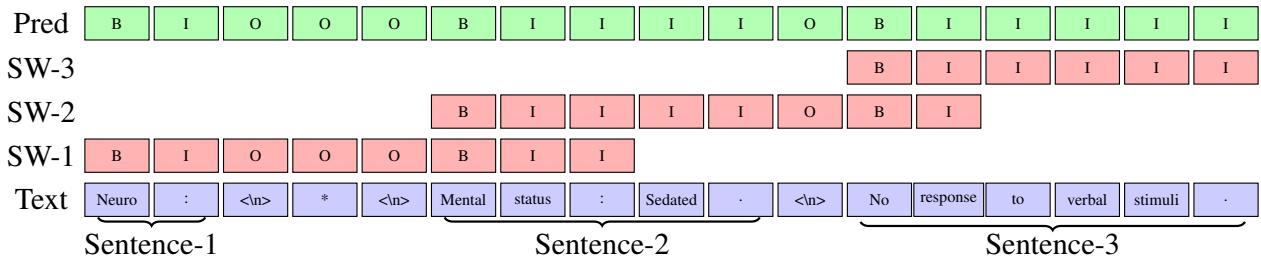

Figure 1: The sliding window algorithm in action. Note how the windows (SW-1, SW-2, SW-3) overlap to ensure context is preserved.

In Figure 1, we see a short text: “Neuro : * Mental status : Sedated . No response to verbal stimuli .”

Here is the step-by-step logic utilized by the algorithm:

- Fill the Window: The algorithm grabs a chunk of text (up to the max length \(l\)) from the document. In the diagram,

SW-1represents the first pass. - Predict: The BERT model predicts the B/I/O tags for everything in that window.

- Find the “Safe” Cut: This is the crucial step. The algorithm looks at the predictions and identifies the start of the second sentence in the window (labeled \(b_{i+1}\)).

- Slide: instead of sliding the window by a fixed number of tokens, the algorithm slides the window so that it starts exactly at that second sentence (\(b_{i+1}\)).

This ensures that the next window (SW-2) starts with a fresh, complete sentence context. The first sentence is finalized and saved, and the process repeats.

If the model can’t find a second sentence in the current window (perhaps it’s one massive run-on sentence), it defaults to sliding by the maximum length \(l\).

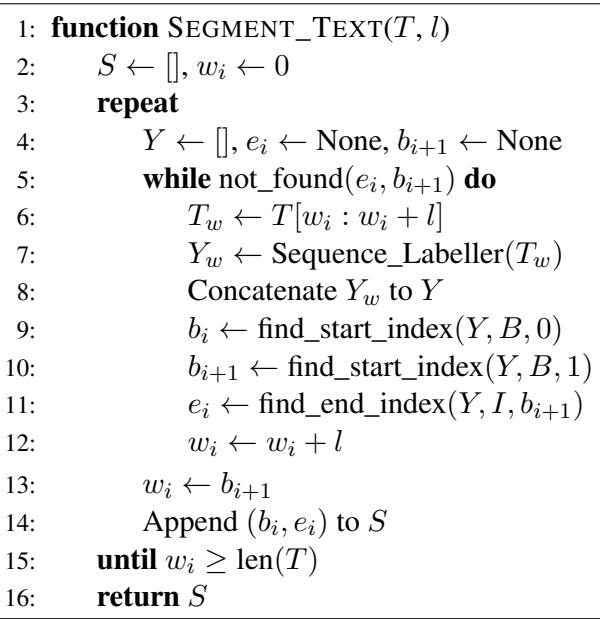

Here is the formal logic behind this process:

By looking at Algorithm 1, we can see the variable \(w_i\) tracking the current position in the text. Lines 9-11 are doing the heavy lifting: identifying the boundaries of the first complete sentence (\(b_i\) to \(e_i\)) and the start of the next one (\(b_{i+1}\)), effectively “locking in” the first sentence and moving the window to the start of the next one.

The Data Gap

To prove this method works, the researchers faced a hurdle: there were no publicly available, manually annotated datasets for sentence segmentation in clinical notes. Most existing datasets were “silver-standard”—generated automatically by tools like CoreNLP—which reinforces the very errors this paper aims to solve.

The authors created a new dataset based on the MIMIC-III corpus (a famous database of de-identified health data). They manually annotated 90 clinical notes.

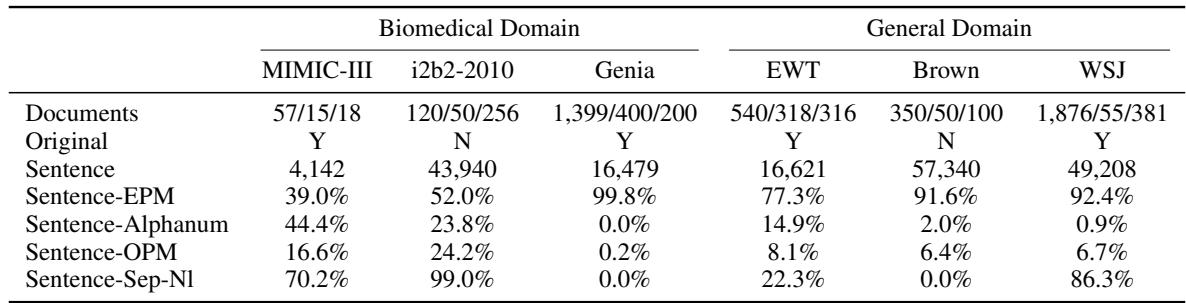

This annotation process revealed just how different clinical data is from the standard corpora used to train NLP tools. Let’s examine the statistics:

Take a close look at Table 1, specifically the Sentence-EPM row.

- In the Genia dataset (biomedical abstracts), 99.8% of sentences end with a standard punctuation mark.

- In WSJ (Wall Street Journal), 92.4% end with punctuation.

- In MIMIC-III (Clinical notes), only 39.0% of sentences end with punctuation.

This single statistic explains why off-the-shelf tools fail. If your tool looks for a period to find a sentence, it will miss 61% of the sentences in a clinical note.

Furthermore, look at Sentence-Alphanum. In MIMIC-III, 44.4% of sentences end with a letter or number (e.g., “Pt denies pain”). In the Wall Street Journal, that happens only 0.9% of the time. This is a fundamental structural difference in the language.

Experiments and Results

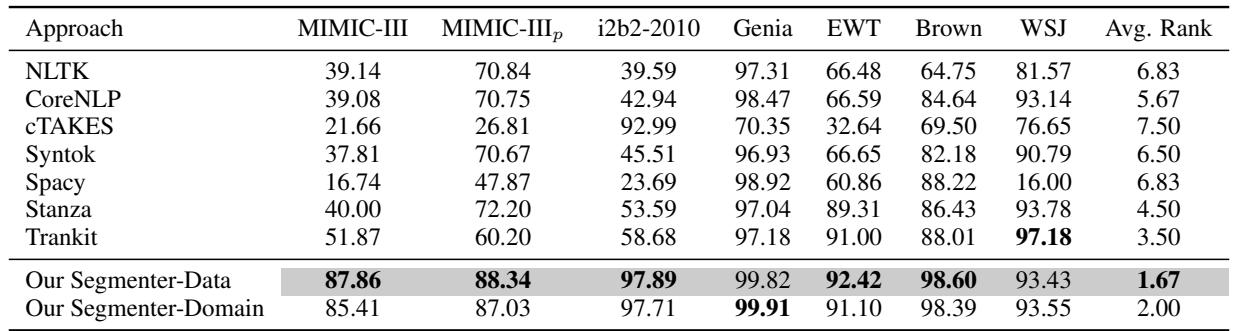

The researchers compared their Segmenter against seven industry-standard tools: NLTK, CoreNLP, cTAKES (specifically designed for clinical text), Syntok, spaCy, Stanza, and Trankit.

They trained two versions of their model:

- Segmenter-Data: Trained specifically on the target dataset.

- Segmenter-Domain: Trained on a combination of datasets within the same domain (e.g., all biomedical data combined).

Performance on Clinical Data

The results on the MIMIC-III dataset were staggering.

In Table 2, look at the MIMIC-III column.

- cTAKES (the clinical tool) achieved an F1 score of 21.66.

- spaCy achieved 16.74.

- CoreNLP achieved 39.08.

- Our Segmenter-Data achieved 87.86.

This is not a marginal improvement; it is a paradigm shift. The F1 score (a measure combining precision and recall) jumped by nearly 50 points compared to standard tools.

Even when the authors tried to “help” the other tools (the MIMIC-III_p column) by manually cleaning up the output rules, their model still outperformed the best competitor by over 15%.

Generalizability

A common fear with deep learning models trained on niche data is that they will “overfit” and fail when shown normal text. However, the results show that this approach is robust.

On the WSJ and Brown corpora (Standard English), the Segmenter performed competitively (93-98% F1), often beating or matching tools designed specifically for standard English.

Cross-Domain Robustness

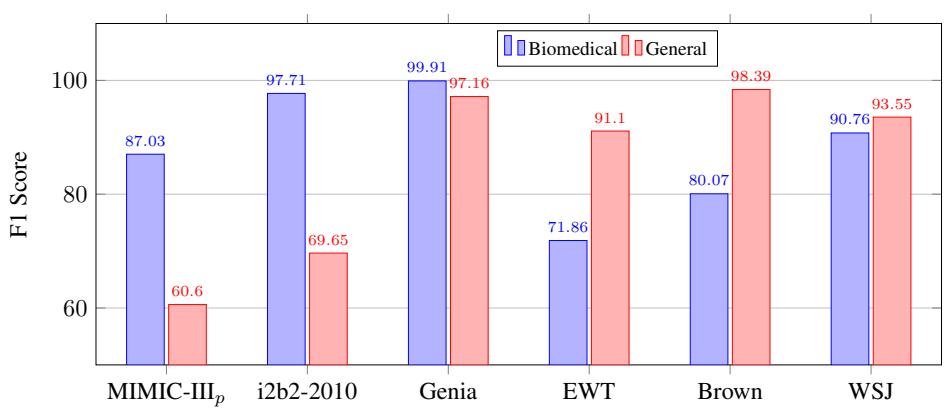

The authors also tested how well a model trained on one domain performs on another.

Figure 3 illustrates this stability.

- The Blue Bars represent the model trained on Biomedical text.

- The Red Bars represent the model trained on General text.

While the biomedical model performs best on biomedical data (MIMIC, i2b2, Genia), it retains respectable performance on general text (EWT, Brown, WSJ). This suggests that the sequence labeling approach learns something fundamental about sentence structure, not just domain-specific vocabulary.

Why Does It Win? The Edge Cases

To understand exactly where the improvement comes from, the researchers broke down performance by sentence type.

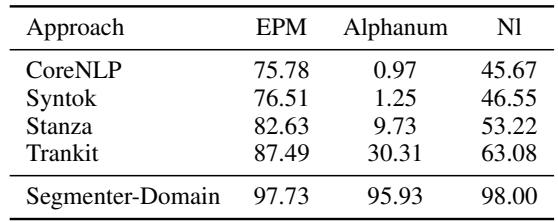

Table 3 reveals the “killer feature” of this approach.

- Sentence-EPM (Ending with Punctuation): Everyone does reasonably well here.

- Sentence-Alphanum (Ending with text/numbers): This is the game-changer.

- CoreNLP: 0.97% recall.

- Trankit: 30.31% recall.

- Segmenter-Domain: 95.93% recall.

Because the Segmenter uses context (embeddings) rather than explicit rules, it can identify that a sentence has ended even if the writer didn’t type a period. It sees the semantic shift in the words.

Conclusion and Implications

The research presented in this paper highlights a critical lesson for students and practitioners of NLP: Data determines architecture.

Tools built for the internet or formal literature rely on assumptions (like proper punctuation) that simply do not hold in high-stakes environments like healthcare. By shifting from a rule-based perspective to a sequence labeling perspective, and solving the length constraint with a dynamic sliding window, the authors created a system that aligns with the messy reality of clinical data.

Key Takeaways

- Context is King: Punctuation is a helpful signal, but it is not a requirement for defining a sentence. Deep learning models can infer boundaries from semantic context.

- Dynamic Processing: The sliding window algorithm allows BERT-based models to handle real-world document lengths without arbitrarily fragmenting sentences.

- Domain Specificity: While general tools are getting better, domain-specific training (on actual clinical notes) remains essential for usable performance in healthcare applications.

For downstream tasks like extracting patient symptoms or automating billing codes, this improvement in segmentation is the difference between a system that works and a system that hallucinates. As we move toward more AI integration in healthcare, “boring” infrastructure tasks like sentence segmentation will be the silent engines driving the revolution.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2776/images/cover.png)