LlamaDictionary: When LLMs Become Dynamic Dictionaries

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), we have a bit of an interpretability problem. When a state-of-the-art model processes a word, it converts it into a vector—a long string of numbers representing that word in a high-dimensional geometric space. While these vectors (embeddings) are mathematically powerful, they are opaque to humans. If you look at a vector, you can’t “read” what the model thinks the word means.

On the other hand, we have dictionaries. They are the gold standard for human interpretability. If you want to know what “bank” means in a specific sentence, a dictionary gives you a clear, text-based definition. However, dictionaries are static; they can’t always capture the nuance of a word used in a brand-new context or a creative metaphor.

What if we could combine the two? What if a model could generate a dictionary-style definition for a word on the fly, based on how it’s used in a specific sentence? And crucially, could we use these generated definitions as a new way to model meaning computationally?

That is the core question behind the paper “Automatically Generated Definitions and their utility for Modeling Word Meaning.” The researchers introduce LlamaDictionary, a fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) designed to generate concise sense definitions, and demonstrate that these definitions can achieve state-of-the-art results in complex semantic tasks.

The Shift to Generative Meaning

To understand why this paper is significant, we need to look at the history of modeling word meaning.

- Static Embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec): Every word had one fixed vector. “Apple” (the fruit) and “Apple” (the company) shared the same representation.

- Contextualized Embeddings (e.g., BERT): The vector for “Apple” changes depending on the surrounding words. This was a massive leap forward, but the representation remained a vector of numbers—interpreting why the vector changed required complex probing.

- Generative Definitions (This approach): Instead of just producing a vector, the model generates a text definition.

The researchers argue that automatically generated definitions offer a dual advantage. First, they distill the information in a sentence, abstracting away the noise of the context to find the core meaning. Second, they are interpretable. A human can read the output and verify if the model understood the word correctly.

The Method: Building LlamaDictionary

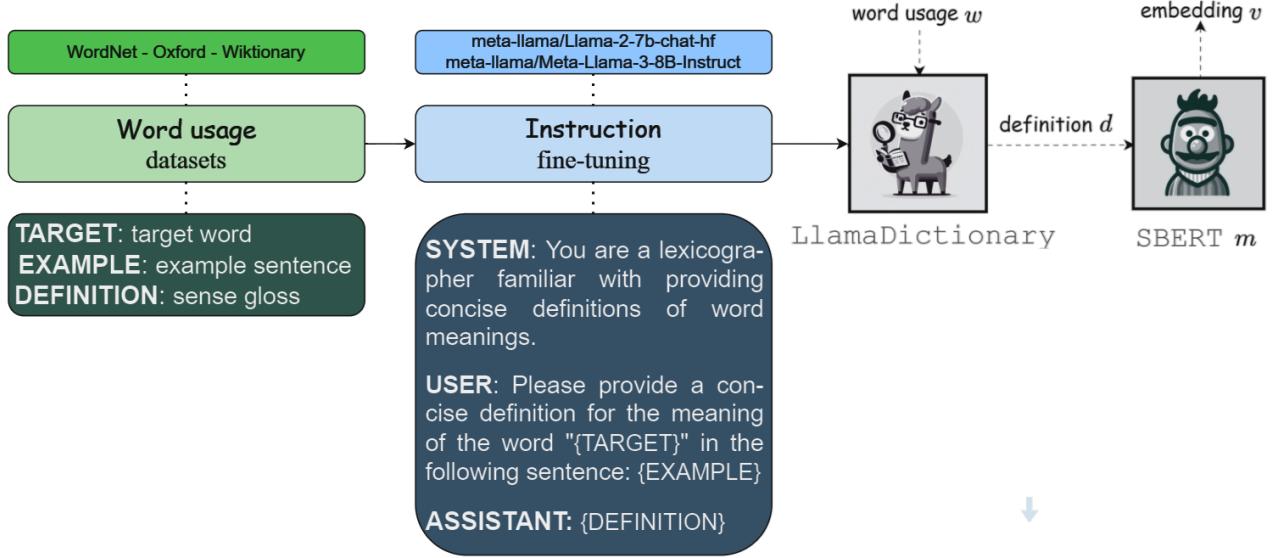

The researchers’ approach is elegant in its simplicity but sophisticated in execution. They treat the problem as a text-generation task. They took two powerful open-source models—Llama 2 (7B parameters) and Llama 3 (8B parameters)—and fine-tuned them specifically to act like lexicographers.

1. The Data

To teach an LLM to write definitions, you need high-quality dictionaries. The team used datasets from:

- The Oxford English Dictionary

- WordNet

- Wiktionary

These datasets provide triples consisting of:

- A Target Word (\(w\)).

- An Example Sentence (\(e\)) containing the word.

- A Definition (\(d\)) explaining the specific sense of the word in that sentence.

2. Instruction Tuning

The models were fine-tuned using Instruction Tuning. This involves feeding the model a prompt that explicitly tells it what to do. The prompt structure looked something like this:

“Please provide a concise definition for the word TARGET in the sentence: EXAMPLE.”

The model is trained to output the correct definition (\(d\)). Because fine-tuning massive models is computationally expensive, the researchers used LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), a technique that freezes the main model weights and only trains a small number of adapter layers. This makes the process much more efficient.

3. The Pipeline: From Text to Vector

Here is where the method gets interesting. Generating the text definition is only step one. To use this for computational tasks (like measuring how similar two words are), the text needs to be converted back into a mathematical format.

The pipeline works as follows:

- Input: A word and its context.

- LlamaDictionary: Generates a text definition.

- SBERT: A Sentence-BERT model encodes that definition into a vector.

Instead of embedding the word token directly (as a standard Transformer would), they embed the definition of the word.

As shown in Figure 1, the model takes a word usage (e.g., “revitalize” in a sentence about food), generates a human-readable definition (“Give new life or energy to”), and then converts that definition into a vector (\(v\)).

Experiment 1: Can it Write Good Definitions?

The first evaluation is straightforward: Does LlamaDictionary write good definitions?

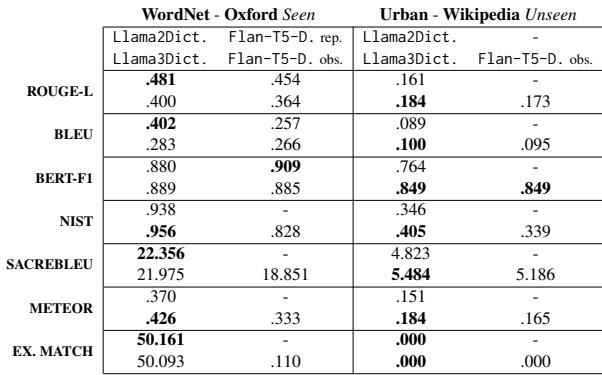

The researchers tested the model on “Seen” benchmarks (datasets like Oxford and WordNet that were part of the training distribution) and “Unseen” benchmarks (datasets like Urban Dictionary and Wikipedia that the model hadn’t been fine-tuned on).

They compared LlamaDictionary against Flan-T5-Definition, a previous state-of-the-art model based on the T5 architecture.

Table 6 summarizes the results.

- Seen Benchmarks: LlamaDictionary (both Llama 2 and 3 versions) outperformed the T5-based model across almost all metrics, including BLEU (lexical overlap) and BERT-F1 (semantic similarity).

- Unseen Benchmarks: The results were interesting. While the semantic scores (BERT-F1) remained high, the lexical scores dropped for the Urban Dictionary.

Why the drop on Urban Dictionary? The researchers hypothesize that “safety tuning” is the culprit. Llama models are trained to be safe and polite. Urban Dictionary… is not. The model likely refused to generate slang, offensive, or highly informal definitions present in the ground truth, resulting in lower exact-match scores even if the semantic meaning was captured.

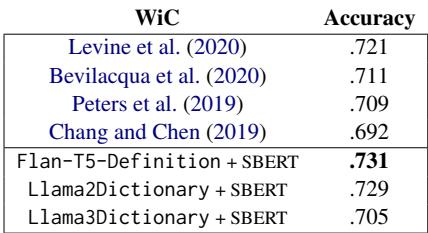

Experiment 2: Word-in-Context (WiC)

Now for the utility test. The Word-in-Context (WiC) task asks a binary question: Given a word used in two different sentences, does it mean the same thing?

Sentence A: “He played a nice tune on the piano.”

Sentence B: “She hummed a tune.”

Answer: True (Same meaning).

Sentence A: “The bank of the river.”

Sentence B: “I put money in the bank.”

Answer: False (Different meaning).

The researchers generated definitions for the target word in both sentences, encoded them using SBERT, and calculated the cosine similarity between the two vectors.

As seen in Table 7, using generated definitions yields excellent results. The Flan-T5-Definition + SBERT approach achieved a new state-of-the-art accuracy of 0.731, with Llama2Dictionary close behind at 0.729. This proves that a generated definition captures the unique sense of a word accurately enough to distinguish between subtle nuances.

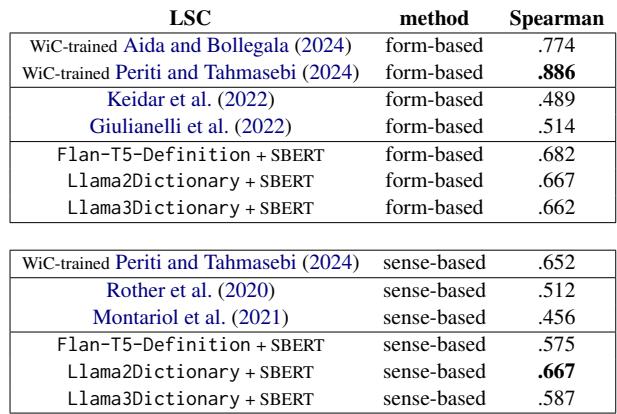

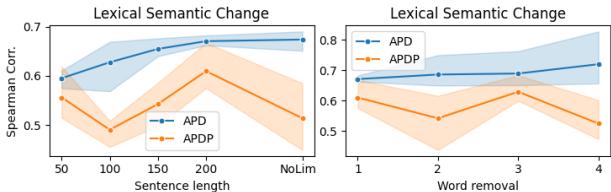

Experiment 3: Lexical Semantic Change (LSC)

Languages evolve. The word “mouse” meant a small rodent for centuries; recently, it started meaning a computer device. The task of Lexical Semantic Change (LSC) involves ranking words by how much their meaning has shifted between two time periods.

The researchers tested two methods using their definition vectors:

- APD (Average Pairwise Distance): The average distance between all definitions of a word in Time Period 1 vs. Time Period 2.

- APDP (Average Pairwise Distance Between Prototypes): Clustering the definitions first to find “senses,” and then measuring the distance between these sense clusters.

Table 8 highlights the findings. The definition-based approach (specifically utilizing Llama2Dictionary) set a new state-of-the-art for interpretable, unsupervised LSC detection, achieving a correlation of 0.667 using the clustering method (APDP).

One fascinating nuance they discovered relates to sentence length.

Figure 3 (Left) shows that the models perform better when they have access to longer contexts (up to 200 characters). If the context is too short, the model struggles to hallucinate a precise definition, which degrades performance. The chart on the right shows that removing “stopwords” (short words) from the generated definitions helps the T5 model but doesn’t affect the Llama models as much, likely because LlamaDictionary was trained to be more concise.

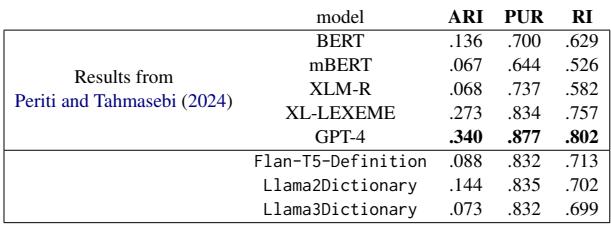

Experiment 4: Word Sense Induction (WSI)

Finally, there is Word Sense Induction. This is the task of automatically discovering how many senses a word has and clustering usage examples into those senses. For example, giving the model 100 sentences containing “bank” and having it automatically separate them into “financial” piles and “river” piles.

Table 9 shows that LlamaDictionary outperforms standard pretrained models like BERT and XLM-R by a significant margin. While it doesn’t beat GPT-4 (which likely has seen the test data during its massive training run), it provides a highly competitive, open-source alternative for clustering word meanings.

Conclusion and Implications

This research bridges the gap between the “black box” of neural networks and the interpretable nature of dictionaries. By fine-tuning Llama models to generate definitions, the authors created LlamaDictionary, a tool that not only explains what a word means in context but also produces representations that are mathematically robust enough to achieve state-of-the-art results in semantic tasks.

The implications are broad:

- Interpretability: We can verify why a model thinks two words are similar by reading the definitions it generates.

- Resource Creation: This technology could automatically generate dictionaries for low-resource languages or specialized domains (like medical or legal texts) where manual lexicography is too expensive.

- Semantic Change: It offers a clearer window into how language evolves, moving beyond abstract vector shifts to concrete changes in definition.

By teaching LLMs to act like lexicographers, we don’t just get better definitions; we get a better way to model the meaning of language itself.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2777/images/cover.png)