Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated an uncanny ability to generate code, summarize history, and even write poetry. Yet, when it comes to rigorous mathematical reasoning—specifically Formal Theorem Proving—they often hit a wall. In the world of formal math, “almost correct” is the same as “wrong.” A proof must be logically sound, step-by-step, and verifiable by a computer program.

While standard LLMs try to solve these problems by guessing the next step based on intuition (a process called forward chaining), human mathematicians often work differently. They look at the goal and ask, “What do I need to prove first to make this goal true?” This is called backward chaining.

In this post, we will deep dive into BC-Prover, a new framework presented by researchers from Alibaba Group and Peng Cheng Laboratory. This paper introduces a method that combines the creative power of LLMs with a structured, backward-chaining strategy to solve complex mathematical proofs in the Lean programming language.

The Challenge: Interactive Theorem Proving

Interactive Theorem Proving (ITP) is like a video game for mathematicians. You are given a starting state (hypotheses) and a final boss (the theorem to prove). You must issue commands, called tactics, to transform the state until the boss is defeated (the goal is proven).

The environment usually involves a proof assistant, such as Lean or Isabelle. These assistants are strict compilers that reject any step that doesn’t follow the rules of logic.

The Problem with “Forward Only”

Most existing AI provers rely on forward chaining. They look at the current hypotheses and predict the next logical step, hoping to eventually stumble upon the goal.

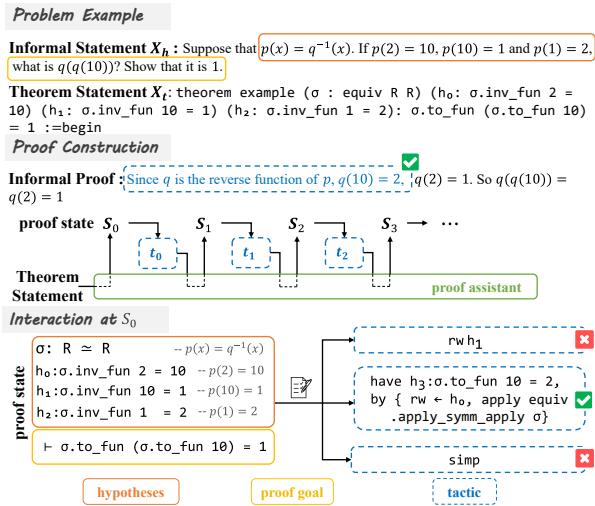

As illustrated in Figure 1, the prover starts with an informal statement and converts it into a formal theorem. In the “Interaction at \(S_0\)” section, you can see the struggle. The goal is to prove a specific value for a function \(\sigma\).

- The prover tries

rw(rewrite) using hypothesis \(h_1\). Fail. - It tries

simp(simplify). Fail. - However, a backward strategy works. By observing the goal, the prover realizes it first needs to prove a sub-goal (\(h_3\)). This corresponds to the colored sentence in the informal proof: “Since q is the reverse function of p…”

Standard LLMs often get lost because the search space of possible forward steps is infinite. Without a plan, they wander aimlessly.

Enter BC-Prover: A Strategic Framework

The authors propose BC-Prover, a framework that doesn’t just guess the next step; it plans the route. It prioritizes pseudo steps—intermediate, structured sketches of the proof—and uses them to guide the rigorous formal proving process.

The Architecture

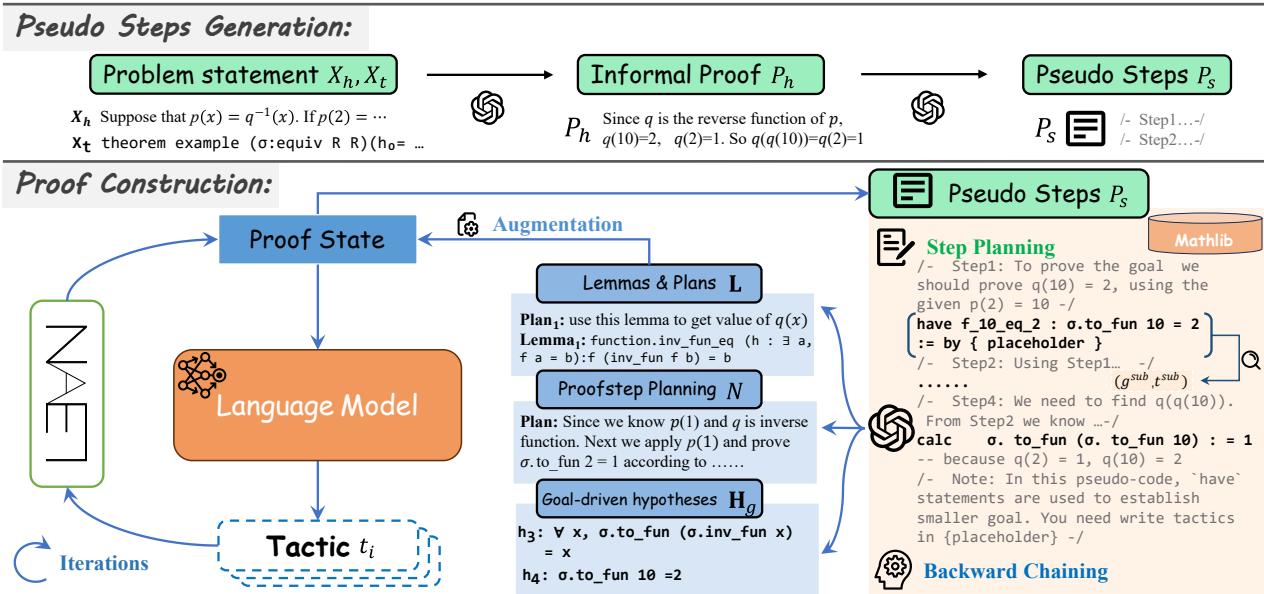

The BC-Prover workflow is divided into two main phases: Pseudo Steps Generation and Proof Construction.

As shown in Figure 2, the process begins by taking the problem statement (\(X_h, X_t\)) and generating an informal proof. This is then refined into pseudo steps (\(P_s\))—a high-level algorithm of how the proof should go.

Once the pseudo steps are ready, the actual interaction with the Lean proof assistant begins. This isn’t a simple loop; it involves three sophisticated components:

- Backward Chaining: Breaking the goal into sub-goals.

- Step Planning: Deciding exactly how to implement the next move.

- Tactic Generation: Writing the actual Lean code.

Let’s break down the mathematics and logic behind these components.

1. Pseudo Steps Generation

Before writing code, a programmer writes pseudocode. Similarly, BC-Prover first translates the math problem into an informal proof (\(P_h\)), and then into structured pseudo steps (\(P_s\)).

\[ \begin{array} { c } { { \mathcal { M } : ( X _ { t } , X _ { h } ) \rightarrow P _ { h } } } \\ { { \mathcal { M } : ( X _ { t } , X _ { h } , P _ { h } ) \rightarrow P _ { s } } } \end{array} \]Here, \(\mathcal{M}\) represents the Large Language Model. By forcing the model to articulate the plan (\(P_s\)) explicitly, the system reduces the chance of the LLM “hallucinating” a path that doesn’t exist.

2. Backward Chaining

This is the core contribution of the paper. In every iteration of the proof, BC-Prover looks at the current pseudo steps (\(P_s\)) and the current state (\(S_i\)) to determine if it should work backward.

It uses the LLM to identify sub-goals (\(g^{sub}\)) and the tactics (\(t^{sub}\)) needed to prove them.

\[ \mathcal { M } : ( P _ { s } , S _ { i } ) \rightarrow \mathbf { H } \]The output \(\mathbf{H}\) is a set of potential sub-goals. The system then asks the Lean proof assistant to verify these sub-goals. If valid, they are added to the list of “Goal-Driven Hypotheses” (\(\mathbf{H}_g\)).

\[ { \mathbf { H } } _ { g } = \operatorname { L e a n } ( { \mathbf { H } } , S _ { i } ) \]Finally, the proof state is augmented. The AI now knows not just what is true (existing hypotheses), but what needs to be true to finish the job.

\[ S _ { i } ^ { \theta } = [ S _ { i } , \mathbf { H } _ { g } ] \]This drastically reduces the search space. Instead of searching for “any valid mathematical move,” the agent searches for “a move that proves this specific sub-goal.”

3. Step Planning & Retrieval

Formal proofs often require specific lemmas from massive libraries (like Lean’s mathlib). An LLM cannot memorize every single lemma perfectly.

BC-Prover employs a Step Planning module. It first describes the current augmented state (\(S_i^\theta\)) in natural language (\(D\)), and then plans the next move (\(N\)).

\[ \begin{array} { c } { { \mathcal { M } : S _ { i } ^ { \theta } \rightarrow D } } \\ { { \mathcal { M } : ( D , S _ { i } ^ { \theta } , P _ { s } ) \rightarrow N } } \end{array} \]Simultaneously, it uses a retriever to find relevant lemmas (\(\mathbf{L}_r\)) from the library and uses the LLM to select the most useful ones (\(\mathbf{L}\)).

\[ \mathcal { M } : ( \mathbf { L } _ { r } , S _ { i } ^ { \theta } , P _ { s } ) \rightarrow \mathbf { L } \]4. The Proofstep Generator

Finally, all this rich information—the current state, the backward-chained sub-goals, the step plan, and the retrieved lemmas—is fed into the generator.

\[ \begin{array} { c } { S _ { i } ^ { * } = [ S _ { i } ^ { \theta } , N , \mathbf { L } ] } \\ { \mathcal { M } : ( S _ { i } ^ { * } ) \rightarrow \{ t _ { i } ^ { 0 } , . . . , t _ { i } ^ { k } \} } \end{array} \]The model outputs a set of candidate tactics (\(t_i\)), which are then executed in Lean to see which one advances the proof correctly.

\[ S _ { j } = \mathrm { L e a n } ( t _ { j - 1 } ^ { ' } , S _ { j - 1 } ) \]Experimental Results

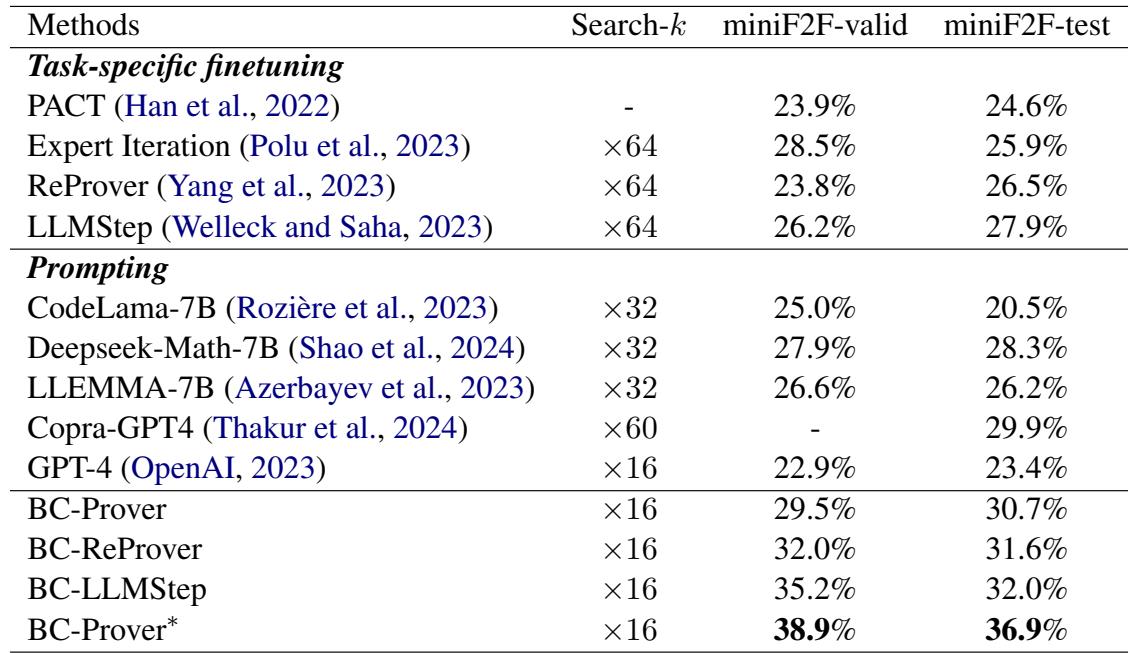

The researchers evaluated BC-Prover on miniF2F, a standard benchmark for formal olympiad-level mathematics. They compared it against several baselines, including pure GPT-4, ReProver, and LLMStep.

Performance on Benchmarks

The results were significant. BC-Prover achieved a much higher “Pass@1” rate (solving the problem in one attempt) compared to the baselines.

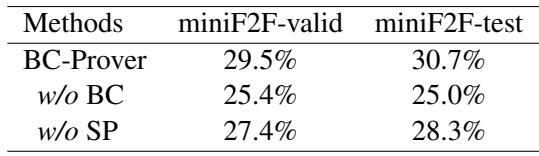

As seen in Table 1, BC-Prover reached 30.7% on the miniF2F-test, outperforming GPT-4 (23.4%) and significantly beating other prompting methods.

Perhaps even more impressive is the Collaborative Setting. When BC-Prover’s logic was combined with task-specific models like ReProver (creating “BC-ReProver”), the performance jumped even higher. This shows that the backward chaining framework is “plug-and-play”—it can enhance existing models.

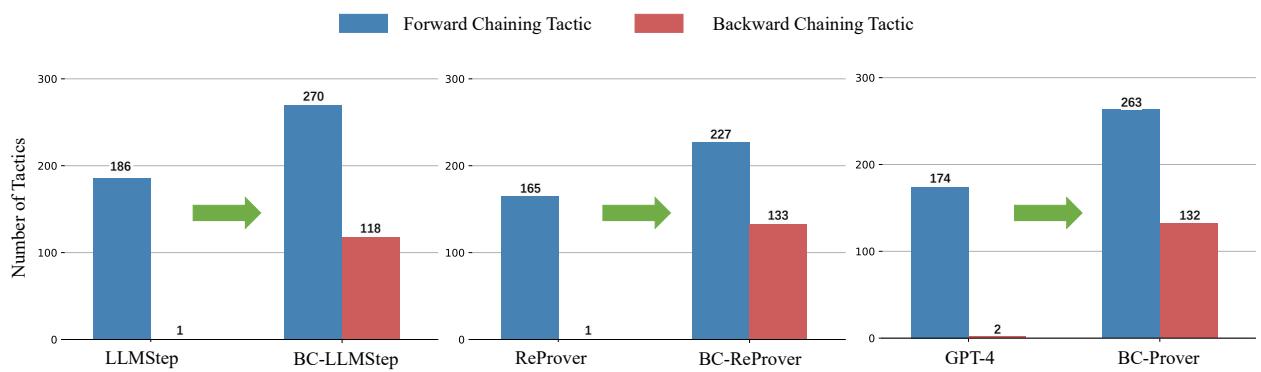

Does Backward Chaining Actually Happen?

One might wonder if the model is truly reasoning backward or just getting lucky. The researchers analyzed the types of tactics generated by the model.

Figure 3 confirms the hypothesis. Standard models like LLMStep and GPT-4 rely almost exclusively on forward chaining (blue bars). BC-Prover (and its collaborative variants) generates a significant number of backward chaining tactics (red bars). This structural shift indicates the model is actively decomposing goals rather than just reacting to hypotheses.

Search Efficiency

A major advantage of planning is efficiency. If you know where you are going, you take fewer wrong turns.

The authors compared the search trees of GPT-4 versus BC-Prover.

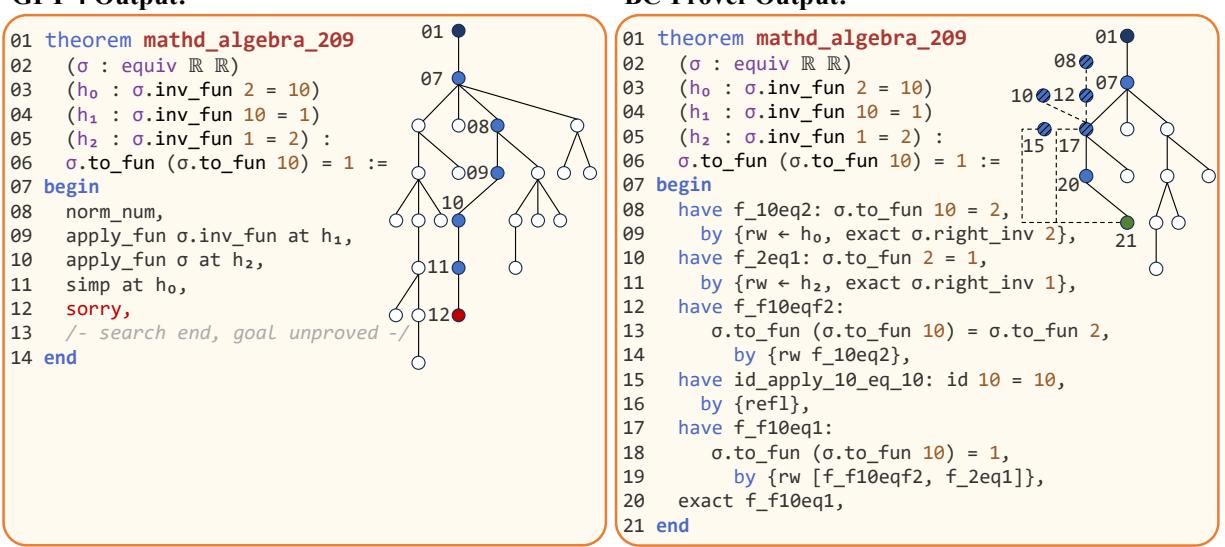

In Figure 4, we see a visualization of the proof process for mathd_algebra_209.

- Left (GPT-4): The model rewrites hypotheses aimlessly. It transforms equations into forms that look complicated but don’t help. It hits a dead end (red node 12) after 25 iterations.

- Right (BC-Prover): The model uses backward chaining (dashed lines). It establishes a sub-goal (lines 08-09) that connects the hypothesis to the goal. It finds the solution in fewer steps and fewer total iterations.

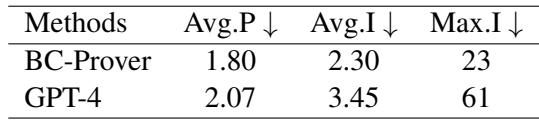

The efficiency data reinforces this:

BC-Prover solves problems with shorter proofs (Avg.P 1.80) and vastly fewer search iterations (Max.I 23 vs 61), saving both time and computational cost.

Why This Matters

The success of BC-Prover highlights a critical limitation in current Generative AI: Forward prediction is not the same as reasoning.

By simply predicting the next token or the next line of code, an AI often lacks the “big picture.” BC-Prover forces the AI to adopt a human-like strategy:

- Draft a plan (Pseudo steps).

- Work backwards from the solution (Backward chaining).

- Verify frequently (Interaction with Lean).

Ablation Study

To prove that every part of the system matters, the authors performed an ablation study, removing components one by one.

Table 2 shows that removing Backward Chaining (w/o BC) resulted in a sharp performance drop (~4-5%). Removing Step Planning (w/o SP) also hurt performance. Both mechanisms are essential for the framework’s success.

Conclusion

BC-Prover represents a significant step forward in automated reasoning. It moves away from the “black box” approach of hoping an LLM intuits the answer, and toward a neuro-symbolic approach where the LLM is guided by structured logic and formal verification.

For students and researchers in AI, the takeaway is clear: LLMs are powerful engines, but they need a steering wheel. Techniques like backward chaining and explicit planning provide that control, allowing us to solve rigorous mathematical problems that were previously out of reach.

Future work in this field will likely focus on improving the quality of the generated sub-goals. As noted in the paper, while BC-Prover generates many useful hypotheses, it also generates some trivial ones (Figure 12 in the paper). Refining this “mathematical intuition” could lead to AI systems that are true partners in scientific discovery.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2780/images/cover.png)