Introduction

In the age of social media, automated content moderation is not just a luxury; it is a necessity. Platforms rely on sophisticated AI models to filter out toxic speech, harassment, and hate speech to keep online communities safe. However, these guardians of digital safety have a hidden flaw: they often become prejudiced themselves.

Imagine a scenario where a user types, “I am a proud gay man.” A toxic content classifier might flag this as “Toxic” or “Hate Speech.” Why? Not because the sentiment is hateful, but because the model has learned a spurious correlation between the word “gay” and toxicity during its training. This phenomenon is known as unintended bias or false positive bias.

Addressing this bias traditionally involves expensive solutions: retraining the model from scratch, augmenting the dataset with thousands of new examples, or adding complex adversarial layers. These methods consume massive computational resources and time.

But what if we could “look inside” the brain of the AI, identify exactly which neurons are holding onto these biased associations, and simply… wipe them out?

This is the premise of BiasWipe, a novel technique presented by researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology Patna, King’s College London, and IIT Jodhpur. In this post, we will explore how BiasWipe uses model interpretability to surgically remove bias from Transformer models (like BERT, RoBERTa, and GPT) without the need for retraining.

The Root of the Problem: Data Distribution

To understand the solution, we first need to understand why models like BERT or GPT-2 develop these biases. The answer lies in the training data.

Language models operate on statistics. If a specific demographic term (like “Muslim,” “Gay,” or “Black”) appears frequently in toxic comments within the training data, the model begins to over-generalize. It creates a shortcut: If this word appears, the sentence is likely toxic.

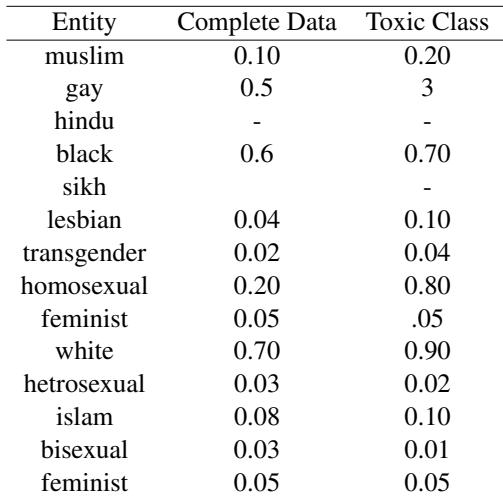

The researchers analyzed the Wikipedia Talk Pages (WTP) dataset, a common benchmark for toxic content detection. The statistical imbalance they found was striking.

As shown in Table 1 above, look at the entity “Gay.” It makes up only 0.5% of the complete dataset, yet it appears in 3% of the toxic comments. Similarly, “Homosexual” appears in 0.20% of the toxic comments but is rare in the overall dataset.

Because of this skew, the model learns that “Gay” is a strong signal for toxicity, regardless of the context. This leads to high False Positive Rates (FPR) for neutral or positive sentences containing these identity terms.

Measuring the Fairness Gap

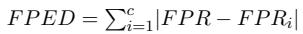

How do we quantify this unfairness? The researchers utilize two specific metrics derived from the template dataset: False Positive Equality Difference (FPED) and False Negative Equality Difference (FNED).

In an ideal, fair world, a model’s error rate should be consistent regardless of the demographic mentioned. FPED measures the deviation of a specific group’s false positive rate from the overall average.

Similarly, FNED measures the deviation for false negatives (when a model fails to catch toxic content directed at a specific group).

If these numbers are high, the model is biased. The goal of BiasWipe is to drive these numbers close to zero without destroying the model’s general accuracy.

Introducing BiasWipe

Existing methods to fix these metrics usually involve “In-processing” (changing how the model learns) or data augmentation. BiasWipe takes a different approach: Post-processing via Unlearning.

The core idea is simple yet powerful:

- Identify: Find the specific weights (neurons) inside the pre-trained model that contribute to the bias.

- Prune: Set those weights to zero (wipe them), effectively making the model “forget” the biased association.

Crucially, this is done after the model is trained. You do not need to restart the expensive training process.

The Methodology: A Surgical Approach

Let’s break down the BiasWipe architecture. The process leverages Counterfactuals and SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), a popular game-theoretic approach to interpret machine learning models.

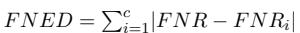

As illustrated in Figure 1, the workflow consists of three major stages:

1. The Counterfactual Dataset

To find the bias, the researchers first create a “Template Dataset.” These are pairs of sentences that are identical except for the presence of a demographic term.

- Actual (\(T_{act}\)): “Abdul is a fantastic gay.” (Contains the entity)

- Counterfactual (\(T_{cou}\)): “Abdul is a fantastic.” (Entity removed)

If the model predicts “Toxic” for the first sentence but “Non-Toxic” for the second, we know the word “gay” is triggering the bias.

2. Peeling Back the Layers: Transformer Neurons

Transformer models are stacked with layers containing Self-Attention mechanisms and Feed-Forward Networks (FFN). The researchers focus on the FFNs because these layers often encode specific patterns and concepts.

Mathematically, the FFN in a transformer layer looks like this:

Here, \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) are weight matrices. These weights determine how the model processes information. BiasWipe aims to find which specific values within \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) are responsible for the “Gay = Toxic” decision.

3. SHAP and Weight Pruning

This is the heart of the algorithm. The researchers apply SHAP to calculate the importance score of every neuron weight for a given prediction.

They calculate two sets of importance scores:

- \(W1_{act}\): The weight importance when processing the sentence with the demographic term.

- \(W2_{cou}\): The weight importance when processing the sentence without the demographic term.

By subtracting these two matrices (\(W1_{act} - W2_{cou}\)), they isolate the weights that react specifically to the presence of the demographic term.

The weights with the highest difference are the culprits. These are the neurons causing the unintended bias. BiasWipe then performs pruning: it selects the top-\(k\) most biased weights and sets them to zero. This effectively cuts the link between the identity term and the toxic classification.

Experimental Results

Does this surgical procedure actually work? The researchers tested BiasWipe on three major language models: BERT, RoBERTa, and GPT-2, using the Wikipedia Talk Pages dataset.

Visualizing the Bias Before Unlearning

First, let’s look at how biased the models were before BiasWipe was applied.

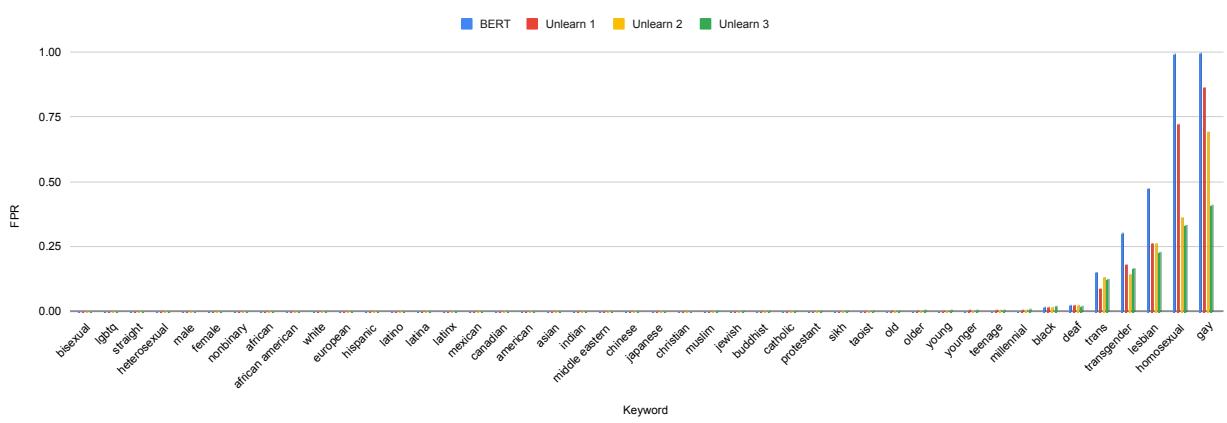

Figure 2 shows the False Positive Rate (FPR) for BERT. Look at the blue bars for “Gay,” “Homosexual,” and “Lesbian.” They are incredibly high, meaning the model almost always thinks sentences containing these words are toxic.

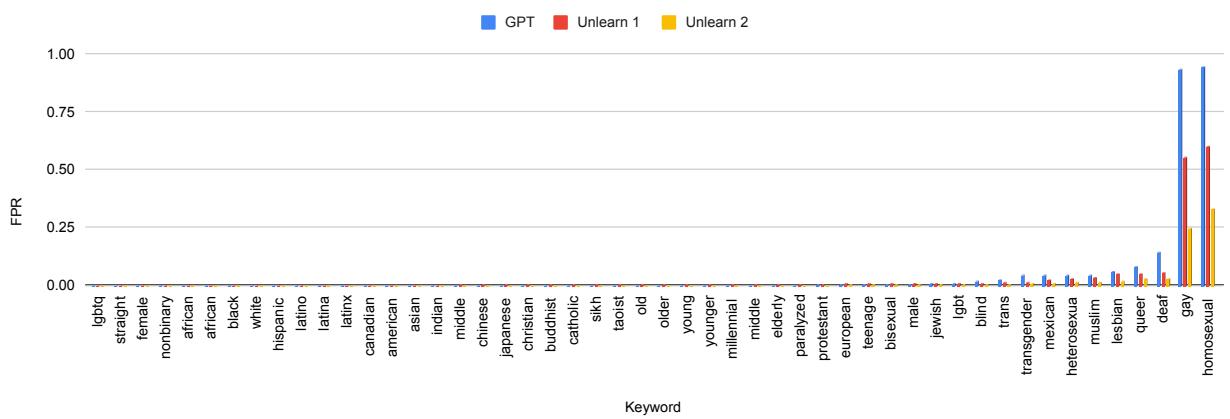

We see a similar, though slightly distinct, pattern for GPT-2:

In Figure 3 (blue bars), GPT-2 exhibits severe bias against “Gay” and “Homosexual” entities, reaching FPRs near 1.0 (100% false positives).

The “Unlearning” Effect

The researchers applied BiasWipe in sequential steps (“Unlearn 1”, “Unlearn 2”, etc.), targeting different biased entities one by one.

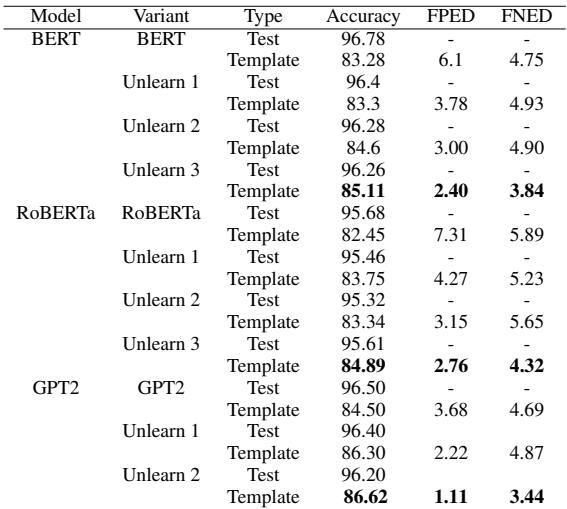

The results, summarized in Table 2 below, are impressive.

Let’s analyze the BERT section of this table:

- Original Model: The FPED (bias metric) is 6.1. The Accuracy on the template set is 83.28%.

- After Unlearn 3: The FPED drops significantly to 2.40.

- Accuracy: Crucially, the Test Accuracy remains steady (from 96.78% to 96.26%).

This confirms that BiasWipe successfully reduced bias (lower FPED) without breaking the model’s ability to detect actual toxicity (stable Test Accuracy).

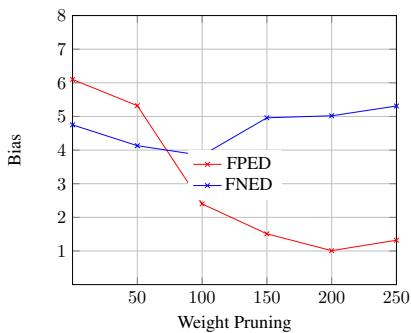

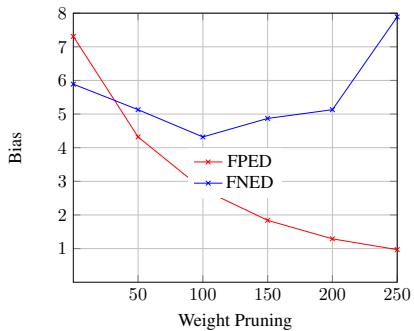

How Many Weights Should We Prune? (Ablation Study)

One might wonder: why not prune all the weights? Or why stop at 10 or 100?

Pruning is a balancing act. If you prune too few weights, the bias remains. If you prune too many, you start damaging the model’s general knowledge, leading to a drop in accuracy or an increase in False Negatives.

The researchers conducted an ablation study to find the “sweet spot.”

In Figure 4, we see the impact of pruning count on bias metrics for BERT.

- X-axis: Number of weights pruned.

- Red Line (FPED): As we prune more weights (moving right), bias drops sharply.

- Blue Line (FNED): If we go too far (past 100-150), the False Negative rate starts to creep up.

Figure 5 shows the same for RoBERTa. The trends suggest that pruning around 100 weights is often the optimal strategy to minimize bias while maintaining model stability.

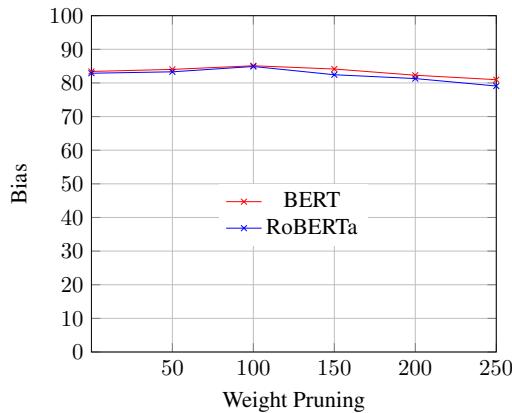

We can also look at the impact on overall accuracy:

Figure 6 confirms that accuracy remains relatively stable up to roughly 100 pruned weights. Beyond that, the surgical removal becomes too aggressive, and the patient (the model) starts to suffer performance degradation.

Qualitative Analysis: Seeing the Shift

To prove that the model’s “reasoning” actually changed, the researchers used SHAP to extract the keywords the model focused on before and after the BiasWipe procedure.

Consider the sentence: “Abdul is a fantastic gay.”

- Original BERT: Focused heavily on the word “gay” and predicted Toxic.

- BiasWipe BERT: Shifted focus to the word “fantastic” and predicted Non-Toxic.

This qualitative shift proves that the model stopped relying on the identity term as a toxicity signal and began looking at the actual sentiment-bearing adjectives.

Conclusion

BiasWipe represents a significant step forward in the quest for fair AI. It tackles the stubborn problem of unintended bias not by retraining models with massive new datasets, but by interpreting and modifying the model’s internal representation.

The key takeaways from this research are:

- Efficiency: BiasWipe is a post-processing technique. It saves the massive environmental and financial costs of retraining Large Language Models.

- Precision: By using Shapley values, it targets only the specific neurons responsible for bias, leaving the rest of the model’s knowledge intact.

- Generalizability: The method proved effective across different architectures (BERT, RoBERTa, GPT-2), suggesting it could be a universal tool for Transformer debiasing.

As AI models continue to grow in size and complexity, “surgical” techniques like BiasWipe will likely become standard tools in the developer’s toolkit, ensuring that our automated systems protect users without silencing marginalized voices. Future work aims to extend this approach to multilingual and code-mixed settings, ensuring fairness across different languages and cultures.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2801/images/cover.png)