Introduction

The rate at which biomedical literature is published is staggering. Every day, thousands of new papers are released, detailing novel drug interactions, genetic discoveries, and disease mechanisms. For researchers and clinicians, keeping up with this flood of information is impossible. Yet, hidden within these unstructured texts are the keys to new cures and therapies.

To manage this, we rely on Information Extraction (IE)—using AI to automatically parse text and convert it into structured databases. This typically involves two steps: Named Entity Recognition (NER) (identifying distinct items like “Aspirin” or “TP53”) and Relation Extraction (RE) (determining how they interact, e.g., “Aspirin inhibits TP53”).

However, biomedical text is notoriously difficult to parse. It is rife with ambiguous terms, nested names, and complex sentence structures. Traditional AI models often struggle here, especially when there isn’t enough labeled training data.

In this post, we will deep dive into a fascinating solution proposed by researchers from Tsinghua University and Harvard University: Bio-RFX (Biomedical Relation-First eXtraction). This model flips the script on traditional extraction methods by identifying the relationship first to better understand the entities, achieving state-of-the-art results even in low-resource scenarios.

The Challenge of Biomedical Text

Before understanding the solution, we must appreciate the problem. General-domain NLP models (like those used for news or Wikipedia) often crash and burn when applied to biomedicine. Why?

1. Ambiguity

In general English, an “Apple” is usually a fruit or a company. In biology, the same acronym can mean entirely different things depending on the context.

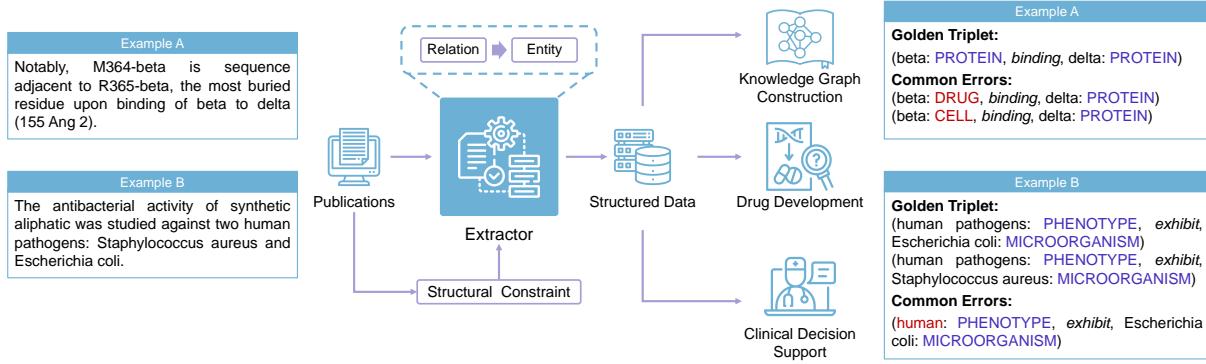

Consider Figure 1 below. In Example A, the terms “beta” and “delta” are incredibly vague. They could be cell types, drugs, or proteins. However, the sentence mentions a binding relation. If we know they are binding, we can infer they are likely proteins. Traditional models that try to identify the entity before understanding the relationship often misclassify these terms.

2. Nested and Overlapping Entities

Biomedical names are often long and descriptive. Look at Example B in Figure 1. “Human” is an entity. “Human pathogen” is another entity. “Staphylococcus aureus” is a third. A model needs to be smart enough to extract “human pathogen” as the subject of the sentence, rather than just “human,” while ignoring the overlap if it’s irrelevant.

3. The Low-Resource Bottleneck

Deep learning models are data-hungry. They usually require thousands of hand-labeled sentences to learn patterns. In biomedicine, labeling data requires PhD-level experts, making it expensive and slow. We need models that can learn effectively from just a few hundred examples.

The Bio-RFX Approach: Relation First

Most extraction systems follow a “Pipeline” approach: find entities first, then look for relations. If the model fails to find the entity correctly (e.g., calling a gene a drug), the relation extraction step has no chance of success.

Bio-RFX proposes a different philosophy: Relation-First.

The hypothesis is simple: The relation expressed in a sentence is often easier to detect than the specific boundaries of an entity, and knowing the relation provides strong clues about what the entities are.

The framework operates in four distinct stages, utilizing a concept called “Structural Constraints” to guide the AI.

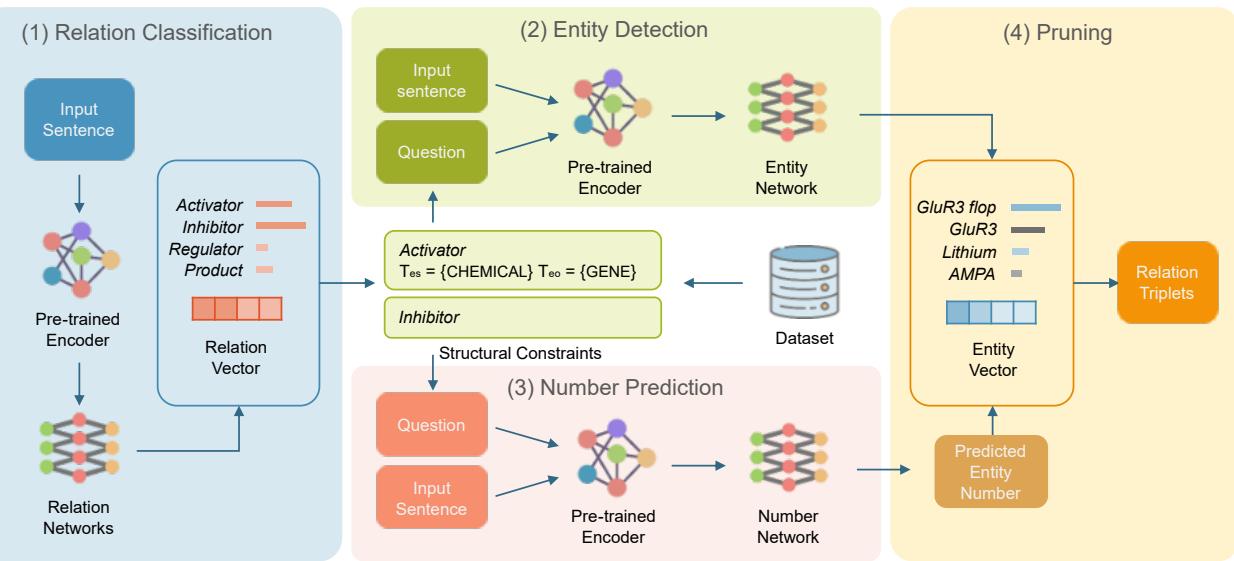

Let’s break down the architecture shown in Figure 2.

Step 1: Relation Classification

Instead of looking for words immediately, Bio-RFX first reads the entire sentence to determine what kind of interactions are present. It uses a pre-trained language model (SciBERT) to create a vector representation of the sentence.

It then performs multi-label classification. For example, it might look at a sentence and conclude: “This sentence contains an Activator relation and an Inhibitor relation.”

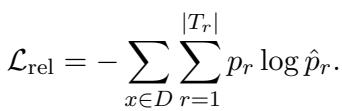

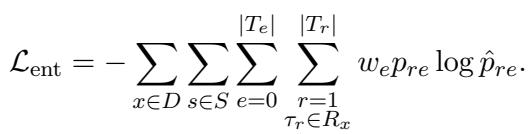

This is trained using a standard cross-entropy loss function:

By detecting the relation first at the sentence level, the model filters out impossible relation types, narrowing down the search space for the next steps.

Step 2: Relation-Specific Entity Extraction

Once the model knows there is an “Activator” relation, it switches to a Question-Answering (QA) mode to find the entities.

This is a clever use of Natural Language Processing. Instead of generic tagging, the model constructs a query based on the relation found in Step 1.

- Standard NER: “Find all chemicals.”

- Bio-RFX RE: “What gene does the chemical activate?”

Notice the specificity? This is where Structural Constraints come in. The model uses prior knowledge that an “activation” interaction typically happens between a Chemical (subject) and a Gene (object). It doesn’t waste time looking for diseases or cell lines for this specific relation.

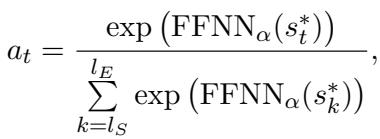

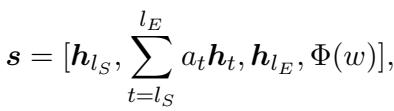

The model uses an attention mechanism to assign scores to different spans of text to see if they answer the question:

It generates a representation for potential entity spans (\(s\)) by combining the start token, the end token, and a width embedding (how long the phrase is):

The model is then trained to minimize the error in identifying these specific spans for the specific relation:

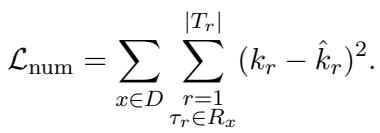

Step 3: Number Prediction

One common issue in extraction is knowing how many entities to look for. Does the sentence mention two drugs? Or five?

Bio-RFX includes a dedicated module that predicts the number of entities (\(k\)) associated with the relation. It treats this as a regression problem. If the ground truth says there are 2 chemicals, and the model predicts 5, it adjusts via the following loss function:

Step 4: Pruning with Text-NMS

Finally, the model needs to clean up the results. Because biomedical terms often nest inside each other (e.g., “lung cancer” inside “non-small cell lung cancer”), the model might suggest overlapping spans.

Bio-RFX uses a Textual Non-Maximum Suppression (Text-NMS) algorithm. It takes the predicted number of entities (from Step 3) and selects the best, non-overlapping spans that match that count, discarding the redundant or lower-confidence guesses.

Experimental Results

The researchers tested Bio-RFX against several strong baselines, including:

- PURE and PL-Marker: Strong pipeline models.

- KECI: A graph-based model using external knowledge bases.

- GPT-4: Tested in a few-shot setting.

They utilized four benchmark datasets: DrugProt, DrugVar, BC5CDR, and CRAFT.

Performance on Standard Datasets

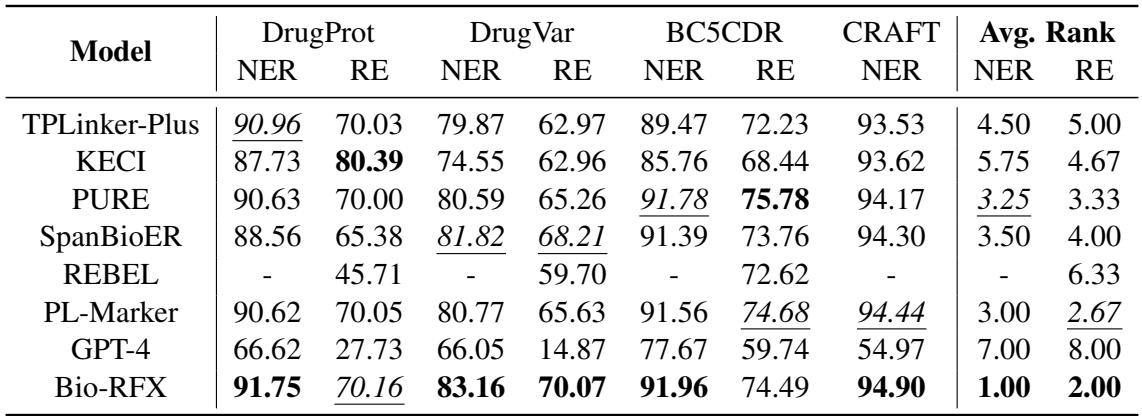

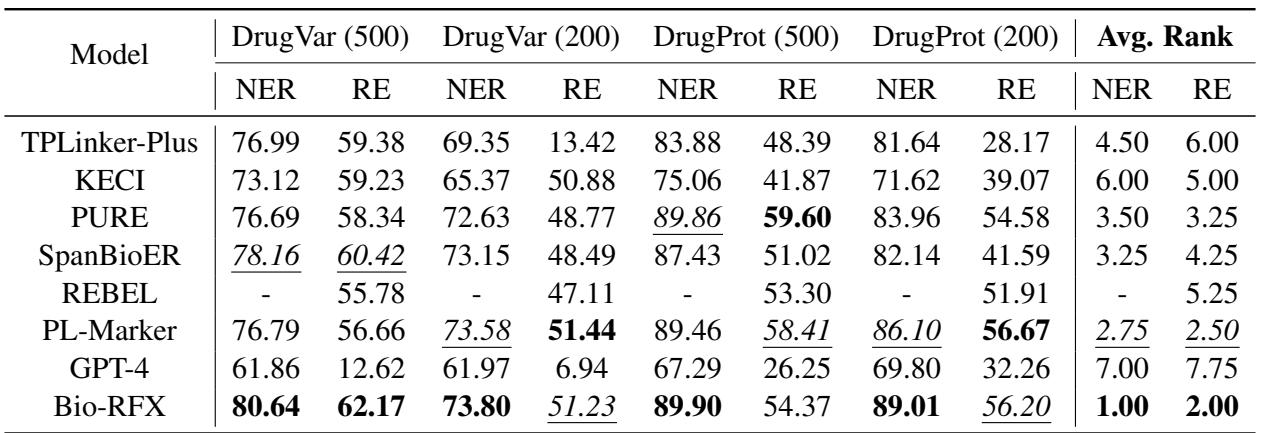

As shown in Table 1, Bio-RFX achieved the best average rank across the datasets. It consistently outperformed previous state-of-the-art models.

Notably, while models like KECI perform well on relation extraction (RE), they often struggle with named entity recognition (NER). Bio-RFX proved to be a balanced performer, excelling in both. Interestingly, GPT-4 lagged significantly behind. While Large Language Models are impressive, specialized fine-tuned models like Bio-RFX still dominate in tasks requiring high precision and domain-specific structural understanding.

The “Low-Resource” Victory

The most impressive results came from the low-resource experiments. The researchers created smaller versions of the datasets, using only a fraction of the training data (e.g., only 200 or 500 sentences).

In these data-scarce scenarios (Table 2), Bio-RFX’s architecture shone brightest.

- Stability: Complex joint models (like TPLinker) fell apart with little data because their tagging schemes were too complex to learn.

- Independence: Because Bio-RFX splits the task (Relation prediction -> Entity extraction), the individual modules are easier to train than one giant network.

- Constraint: By enforcing “Chemicals activate Genes,” the model doesn’t need to learn these rules from scratch—it is structurally guided, which saves data.

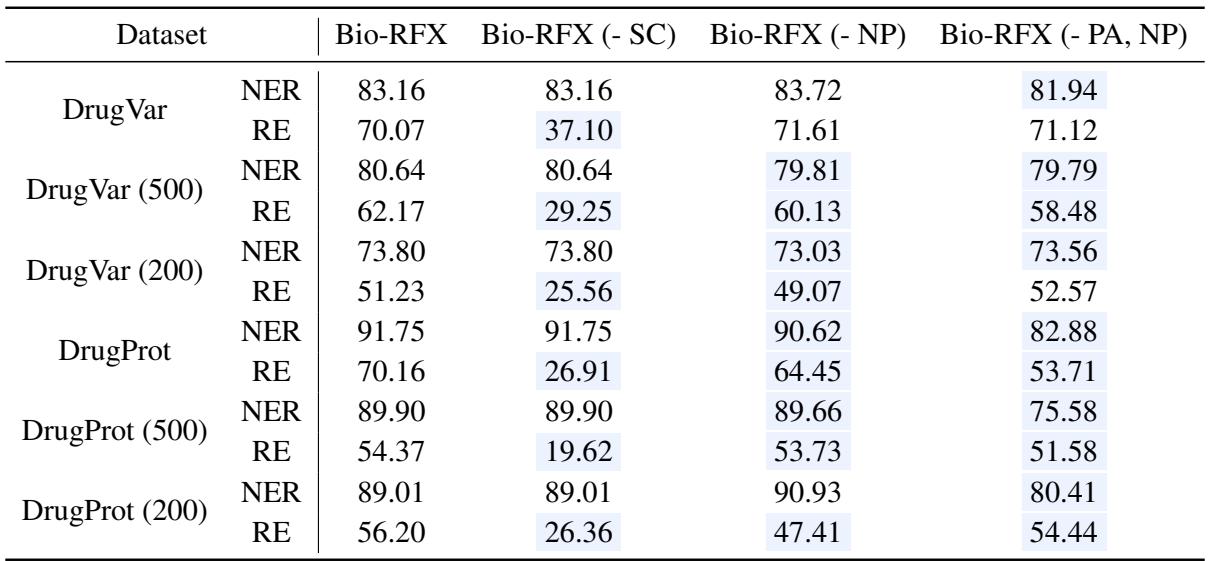

Ablation Study: Do Constraints Matter?

To prove that their design choices were valid, the authors ran an “ablation study”—removing parts of the model to see what breaks.

In Table 3, “Bio-RFX (- SC)” represents the model without Structural Constraints. You can see a massive drop in Relation Extraction (RE) performance (e.g., from 70.07% down to 37.10% on DrugVar). This confirms that constraining the search space based on the relation type is the “secret sauce” of this method.

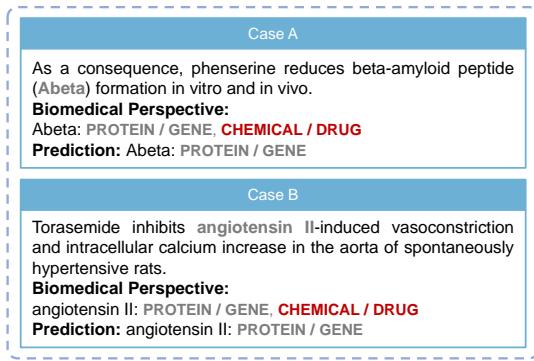

Handling Ambiguity: A Case Study

Finally, let’s look at a qualitative example of how Bio-RFX handles the ambiguity we discussed in the introduction.

In Case A (Figure 3), the term “Abeta” is tricky. It could be a chemical peptide or a protein product. However, the sentence discusses “formation.” In the context of the DrugProt dataset, the model correctly identifies it based on the relation constraints.

In Case B, “angiotensin II” is structurally a peptide (chemical) but functions as a signaling protein. The model correctly identifies it as a GENE/PROTEIN in the context of the interaction described, matching the ground truth where other models might have been confused by its chemical properties.

Conclusion and Implications

Bio-RFX represents a significant step forward in automated biomedical research. By prioritizing Relations First, the model mimics how experts read: we look for the interaction to understand the participants.

The key takeaways from this research are:

- Context is King: Predicting the relation first provides essential context that resolves entity ambiguity.

- Constraints are Crucial: Hard-coding structural rules (e.g., allowed subject-object pairs) drastically reduces the search space, allowing the model to learn faster with less data.

- Divide and Conquer: Breaking the massive task of extraction into smaller, modular sub-tasks (Classification -> QA -> Pruning) creates a system that is robust and stable, even when labeled data is scarce.

As biomedical data continues to grow, tools like Bio-RFX will be essential in converting raw text into structured knowledge graphs, accelerating drug discovery and clinical decision support systems. While GPT-4 and generative AI grab the headlines, highly specialized, structurally constrained architectures remain the gold standard for precision science.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2802/images/cover.png)