Introduction

In the current landscape of Natural Language Processing (NLP), the Transformer architecture reigns supreme. From ChatGPT to Llama, the mechanism of self-attention has unlocked incredible capabilities in generation and reasoning. However, this power comes with a significant computational cost. Attention scales quadratically with sequence length, and the Key-Value (KV) cache grows linearly, making the processing of massive contexts increasingly expensive for both training and deployment.

This scaling bottleneck has reignited interest in efficient alternatives, specifically State Space Models (SSMs). Models like Mamba, S4, and Hawk promise the “holy grail” of sequence modeling: linear scaling and a fixed-size state that allows for constant-cost inference. In theory, they are the perfect solution for long-context applications.

However, there is a catch. While SSMs are efficient, they historically struggle with in-context retrieval. If you ask a Transformer to find a phone number mentioned 10,000 tokens ago, it simply “looks back” at the exact token. An SSM, conversely, must rely on its compressed fixed state. If that specific information wasn’t deemed important enough to compress into the state during the pass, it is lost forever.

Most attempts to fix this have focused on architectural changes, such as adding hybrid attention layers. In the paper “Birdie: Advancing State Space Language Modeling with Dynamic Mixtures of Training Objectives,” researchers from George Mason University, Stanford, and Liquid AI propose a different hypothesis. They argue that the problem isn’t just the architecture—it’s the training. By moving beyond standard “next-token prediction” and using a novel training procedure called Birdie, they demonstrate that SSMs can be taught to utilize their fixed states far more effectively, significantly closing the performance gap with Transformers on retrieval-intensive tasks.

Background: The SSM Bottleneck

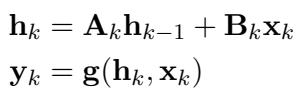

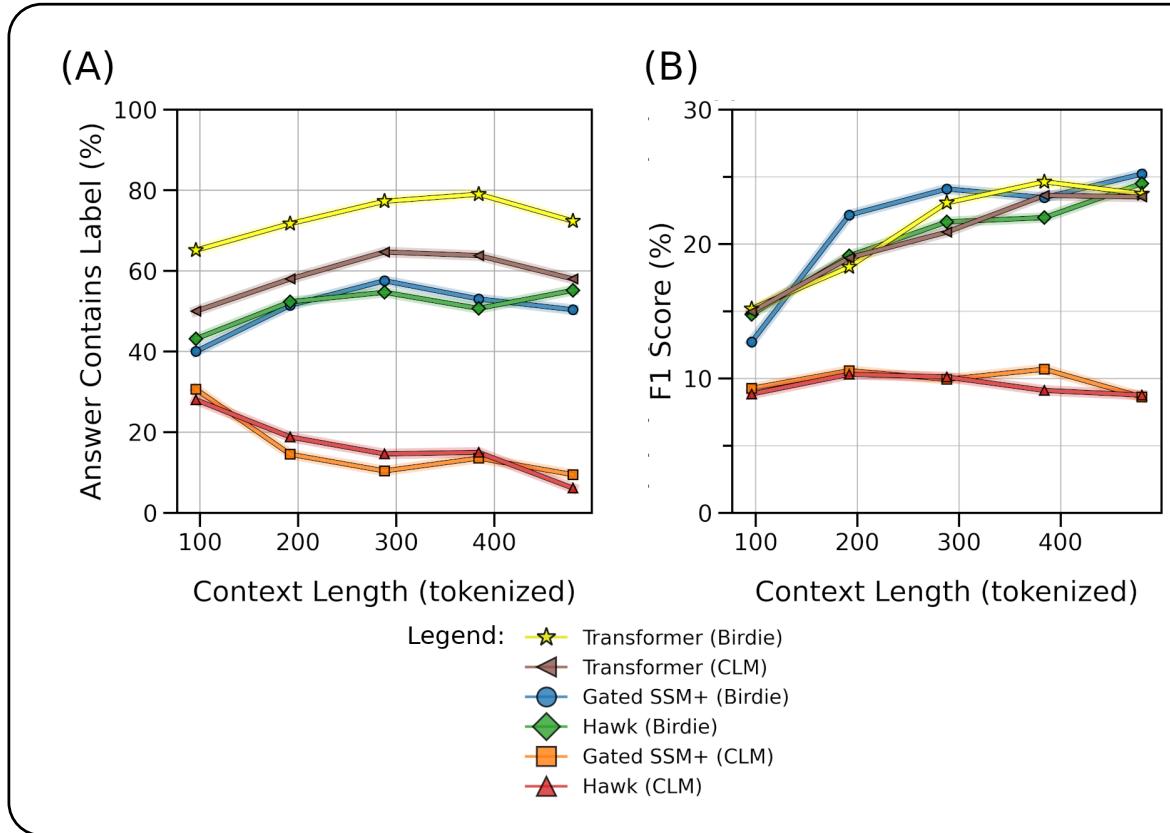

To understand why retrieval is hard for SSMs, we must look at how they process data. Unlike a Transformer, which keeps a history of all previous tokens (the KV cache), an SSM relies on a recurrent update rule. At any time step \(k\), the model updates a hidden state \(\mathbf{h}_k\) based on the previous state and the current input \(\mathbf{x}_k\).

As shown in the equation above, the state \(\mathbf{h}_k\) is the only memory the model has of the past. This creates a “bottleneck.” As the sequence length grows, the model must decide what information to keep and what to discard (or “forget”) to fit everything into this fixed-size vector.

Most SSMs are trained using Causal Language Modeling (CLM), commonly known as next-token prediction. The researchers argue that CLM is insufficient for training SSMs to manage this memory bottleneck. In many cases, predicting the next word only requires local context (the previous few words), meaning the model is rarely penalized for failing to remember long-term dependencies. Consequently, the model never learns to efficiently compress and retrieve distant information.

The Birdie Method

The core contribution of this paper is Birdie, a new pre-training procedure designed to force SSMs to maximize the utility of their fixed state. Birdie relies on three methodological pillars: Bidirectional Processing, New Pre-training Objectives, and Dynamic Mixtures via Reinforcement Learning.

1. Bidirectional Processing

Standard SSMs process text strictly from left to right (causally). This is necessary for generating text, but during the processing of a prompt (the prefix), the entire context is available. Transformers often utilize this via “Prefix Language Modeling,” allowing the model to “see” the whole prompt at once.

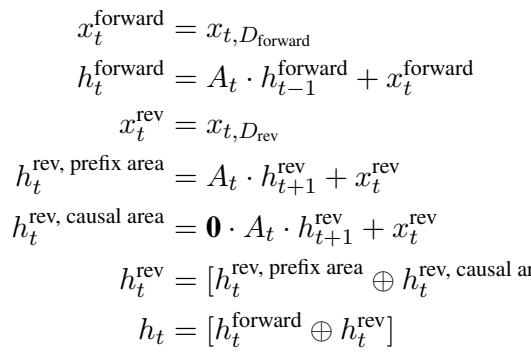

Birdie introduces a bidirectional architecture for SSMs. The idea is to process the context in both forward and reverse directions, allowing the model to capture dependencies that might be missed in a single pass. However, maintaining the ability to generate text causally afterward requires a clever architectural split.

As illustrated in the figure above, the state is divided into forward (\(\mathbf{h}^{\text{forward}}\)) and reverse (\(\mathbf{h}^{\text{rev}}\)) components. Crucially, the researchers mask the dynamics in the causal (generation) area to ensure that information from the future does not leak into the past during the generation phase. This allows the model to build a robust representation of the prompt using bidirectional information, then seamlessly switch to causal generation.

2. Diverse Pre-training Objectives

If CLM is too “easy” to force efficient state usage, the solution is to make training harder. Birdie utilizes a mixture of objectives designed to stress-test the model’s memory.

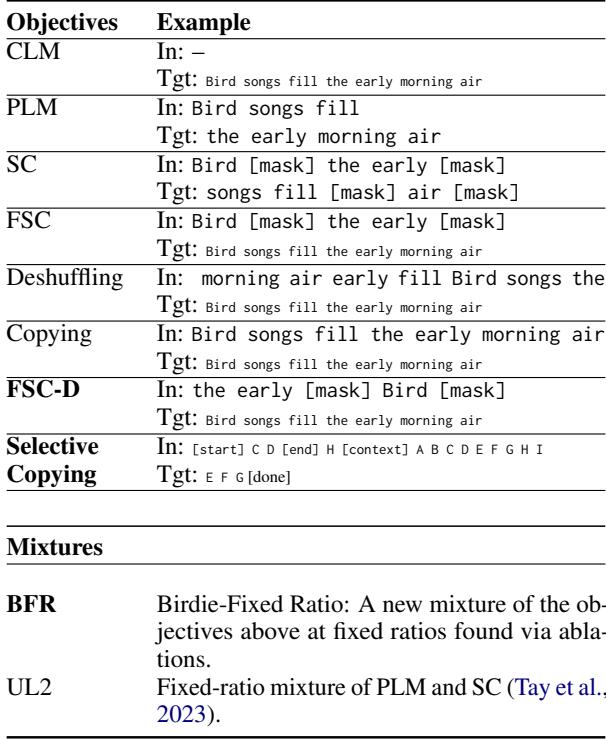

The table above outlines the objectives used:

- Full Span Corruption (FSC): Similar to BERT’s masking, but the model must generate the entire sequence, not just the missing parts. This forces the model to copy context while generating new text.

- Deshuffling: The model receives a shuffled sequence and must reconstruct the original order. Since local syntax is destroyed by shuffling, the model cannot rely on local cues and must use its global state to understand word relationships.

- Copying: simply reproducing the input.

- Selective Copying: A novel task where the model must find specific spans (marked by start/end tokens) within a context and copy them. This mimics retrieval tasks like looking up a specific entry in a database.

3. Dynamic Mixtures via Reinforcement Learning

With so many potential objectives, a new problem arises: how much time should the model spend on each task? Fixed ratios (e.g., 50% CLM, 50% Copying) are rarely optimal throughout the entire training process.

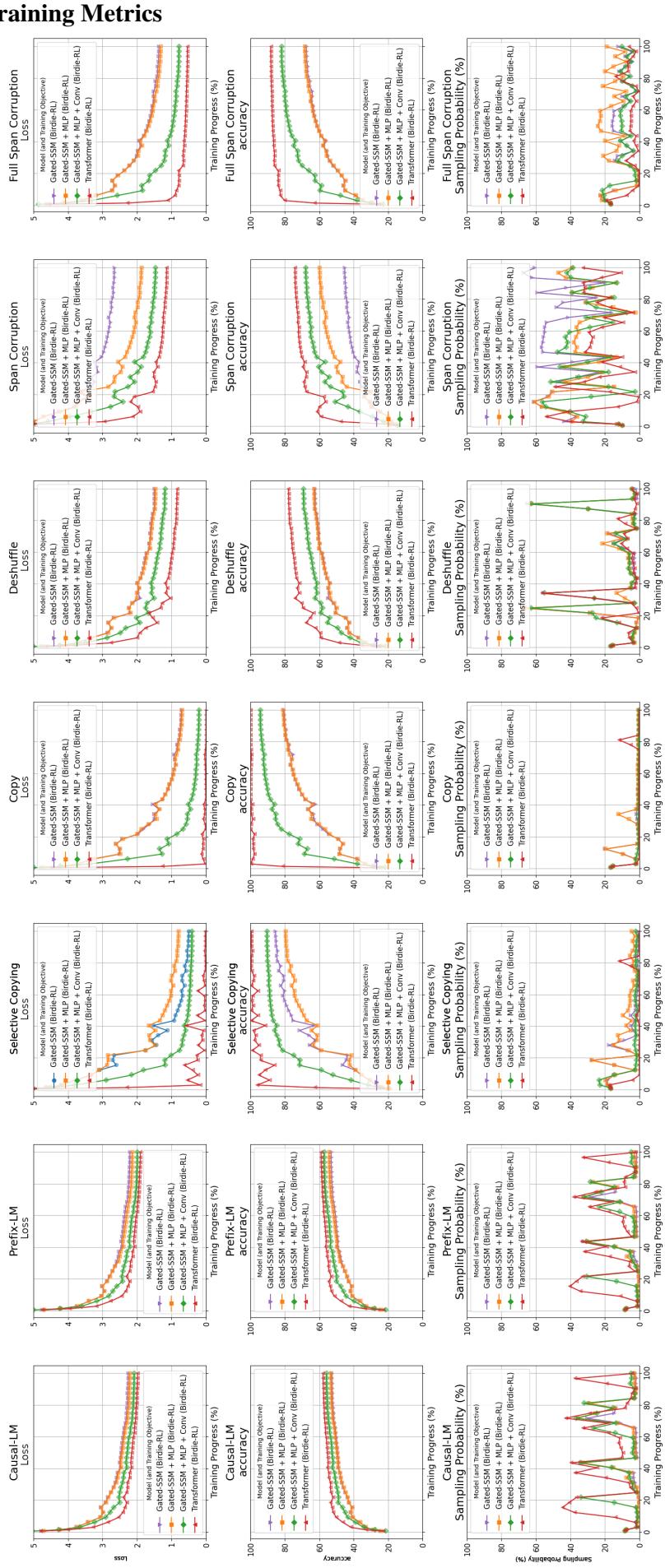

Birdie solves this using a Multi-Armed Bandit approach powered by Reinforcement Learning (RL). A “critic” model (a small Gated SSM) predicts which objective will yield the highest reward (improvement in loss) at the current stage of training.

The visualization above shows this dynamic process in action. The bottom row (“Sampling Probability”) is particularly interesting. We can see the model dynamically adjusting its focus. For instance, the sampling of “Copying” tasks might decrease as the model masters the skill, while other tasks ramp up. This automated curriculum allows the model to focus on what it needs to learn most at any given time, avoiding the need for manually tuned hyperparameters.

4. The Gated SSM Baseline

To prove that the gains come from the training and not just a specific model, the authors test Birdie on a generic Gated SSM baseline. This model combines linear recurrence with gating mechanisms similar to Mamba or LSTMs.

This architecture (Gated SSM+) includes an MLP block and a short 1D convolution to process inputs, providing a strong baseline that is comparable to state-of-the-art models like Hawk.

Experiments and Results

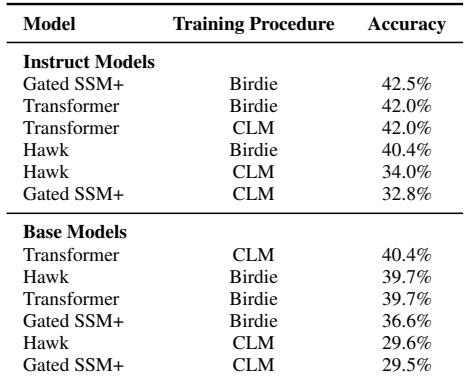

The researchers compared Birdie-trained models against standard CLM-trained models (including Transformers, Hawk, and Gated SSMs) across a variety of benchmarks.

1. General Performance (The “Do No Harm” Test)

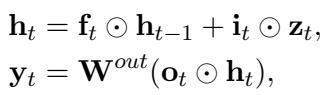

The first question is whether these specialized objectives hurt the model’s general ability to understand language. The authors evaluated the models on the EleutherAI LM Harness, a suite of 21 standard NLP tasks (like ARC, MMLU, and BoolQ).

The results (Table 2) show that Birdie-trained models perform comparably to their CLM counterparts. This confirms that the specialized training improves retrieval capabilities without sacrificing general reasoning or language understanding.

2. The Phone Book Retrieval Test

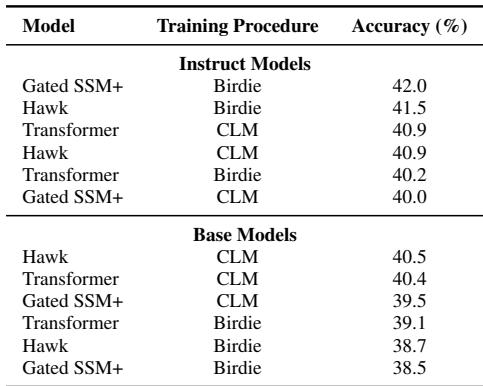

This is the stress test. The model is given a “phone book” of generated names and numbers, followed by a query asking for the phone numbers of specific people. This is pure retrieval—no reasoning, just memory.

Figure 1 (above) tells a compelling story.

- Graph A: Look at the gap between the Transformer (Yellow/Brown) and the standard SSMs (Orange/Red). The standard SSMs fail almost immediately. However, the Birdie-trained SSMs (Blue/Green) significantly close this gap. While they still degrade as the number of retrievals increases, they maintain high accuracy far longer than the standard versions.

- Graph B: This ablation study shows that bidirectional processing alone (Birdie-Causal) or fixed ratios (UL2) are not enough. The full Birdie package (Cyan) is required to achieve high accuracy.

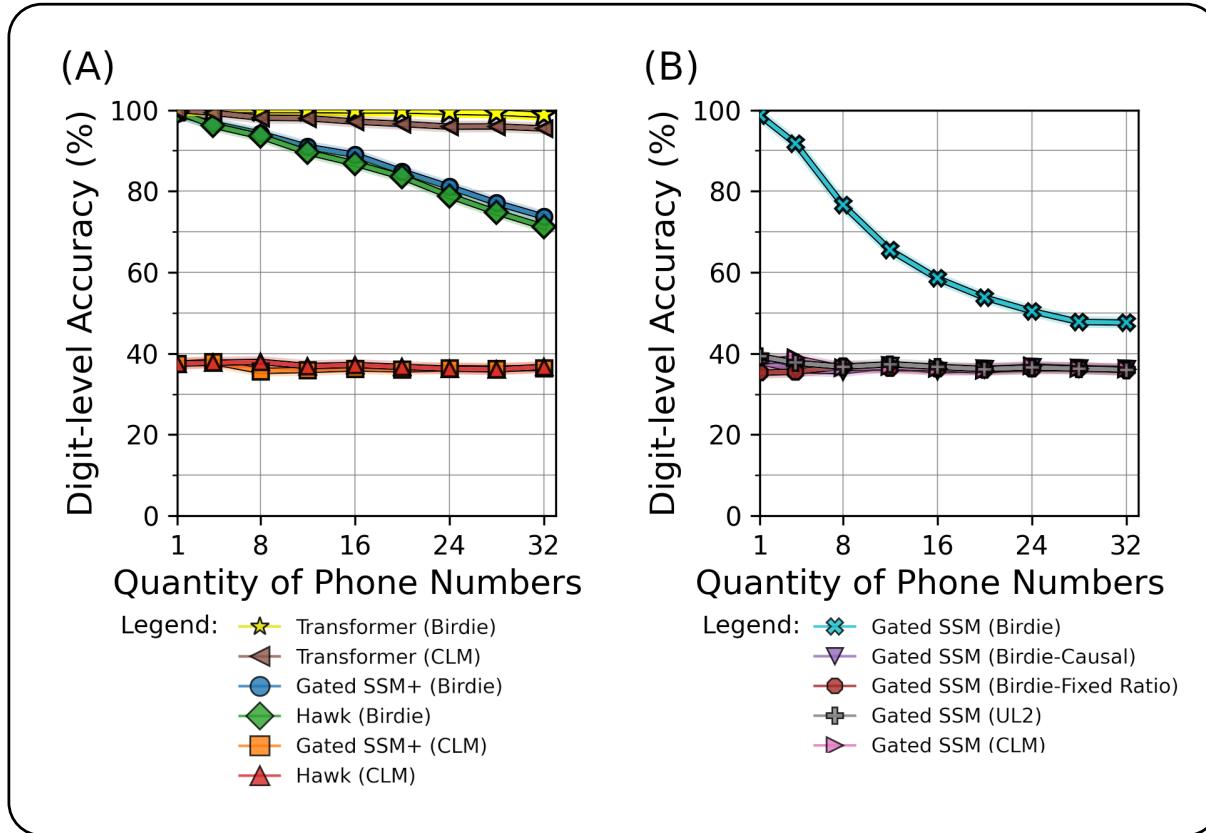

3. Long-Form Question Answering (SQuAD)

Moving to a more realistic task, the authors used the SQuAD dataset, which involves answering questions based on a paragraph of text.

As shown in Graph A (Answer Contains Label), standard CLM-trained SSMs (Orange/Red) degrade rapidly as the context length increases. They simply “forget” the answer if the paragraph is too long. In contrast, Birdie-trained SSMs (Blue/Green) maintain performance curves that rival the Transformer, even at longer context lengths.

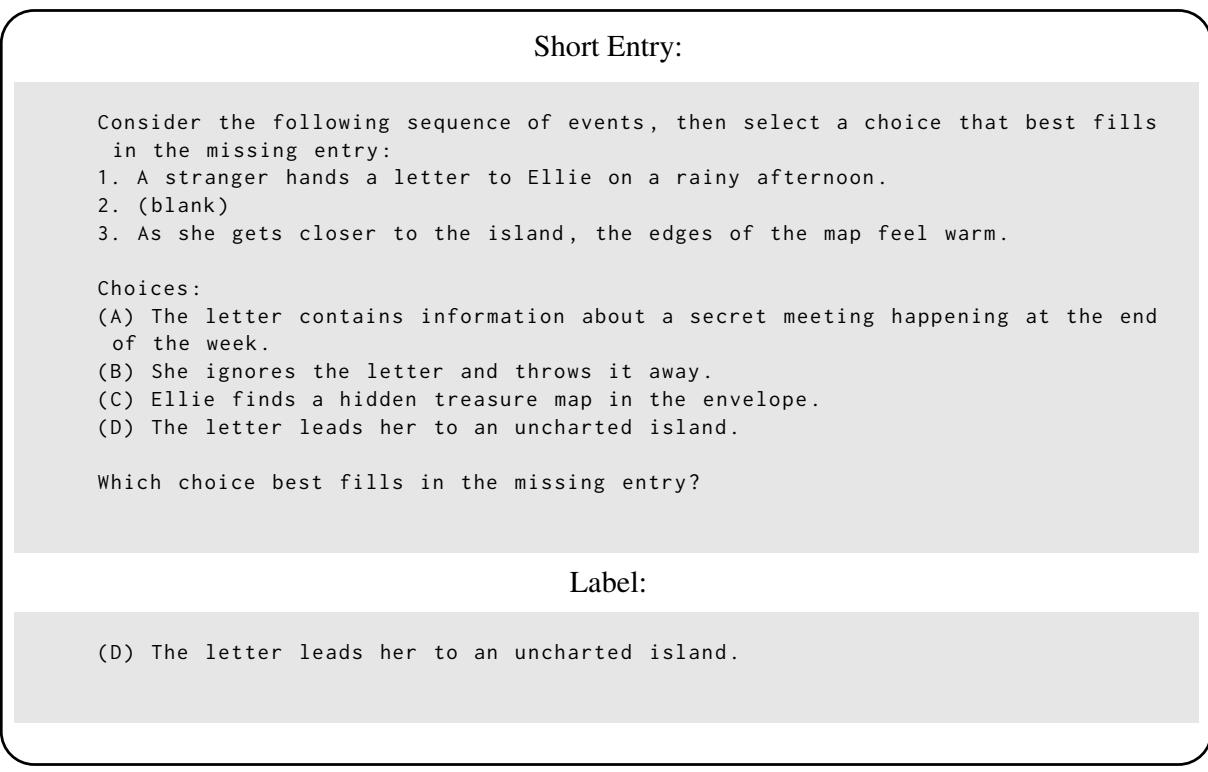

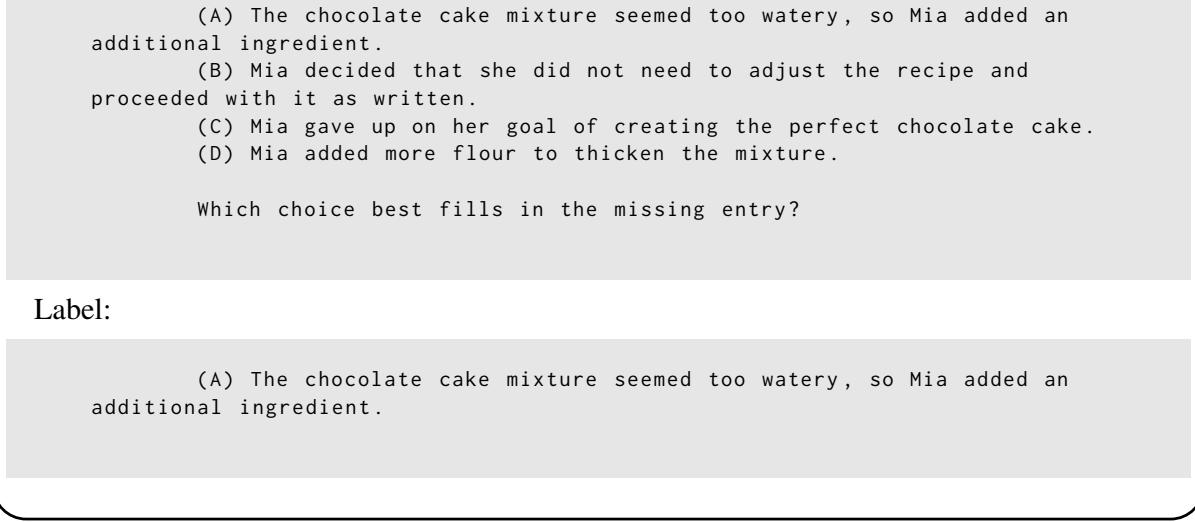

4. Story Infilling

Finally, the authors introduced a new “Infilling” dataset. Models read a story with a missing section and must select the correct text to fill the gap from multiple choices. This requires understanding the full context—both what came before and what comes after the gap.

Again, Birdie-trained models outperform the CLM baselines. Below is an example of a short entry from this dataset to illustrate the task:

And a longer entry requiring deeper context:

Conclusion

The “Birdie” paper offers a pivotal insight into the development of efficient language models. For a long time, the assumption has been that if a State Space Model can’t retrieve information, the architecture is to blame. This work flips that narrative, suggesting that how we teach a model is just as important as the model’s structure.

By forcing SSMs to solve difficult tasks like deshuffling and span corruption—and by allowing them to look at the prompt bi-directionally—Birdie teaches the model to compress information more intelligently into its fixed state.

While a performance gap with Transformers still exists at the extreme end of retrieval tasks, Birdie significantly extends the useful range of SSMs. This suggests that with the right training curriculum, we may not need to sacrifice efficiency for memory, paving the way for faster, lighter, and more capable large language models.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2803/images/cover.png)