Introduction

Imagine you are trying to teach a computer how to handle complex customer service calls—for example, booking a multi-leg flight while simultaneously reserving a hotel and buying tickets for a local attraction. In the world of Artificial Intelligence, specifically Task-Oriented Dialogue (ToD) systems, this is a massive challenge.

The standard approach is Reinforcement Learning (RL). The AI talks to a user simulator, tries to fulfill the request, and gets a “reward” (a positive signal) only if it completes the entire task perfectly. If it fails, it gets nothing or a penalty. This is known as the sparse reward problem. It is akin to trying to learn how to play a piano concerto by hitting random keys and only being told “good job” if you accidentally play the whole piece perfectly on the first try.

To fix this, researchers often use Curriculum Learning (CL). The idea is simple: teach the AI simple tasks first (like booking just a flight), and once it masters those, move to harder tasks. But there is a catch: this assumes you have a list of simple tasks ready to go. In complex, real-world environments, those intermediate “stepping stone” goals often don’t exist. The AI is faced with a sheer cliff of difficulty with no handholds.

In this post, we will deep dive into a solution proposed by Zhao et al. called Bootstrapped Policy Learning (BPL). This framework doesn’t just look for an easier path; it creates one. By dynamically breaking down complex goals into solvable subgoals (Goal Decomposition) and progressively making them harder (Goal Evolution), BPL allows dialogue agents to build their own ladder to success.

The Problem: The Missing Rungs

To understand why BPL is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of current methods.

In a standard pipeline, a dialogue policy (the brain of the chatbot) decides what to say based on the current state of the conversation. When training this policy with RL, the agent explores different actions. However, complex goals require long sequences of correct actions.

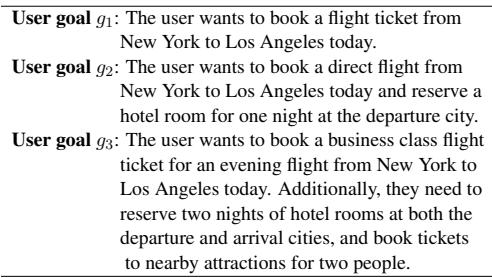

Consider the following examples of user goals:

In a perfect Curriculum Learning scenario, we would train the agent on \(g_1\) (simple flight), then \(g_2\) (flight + hotel), and finally \(g_3\) (flight + hotel + attraction). This provides a smooth knowledge transition.

However, in many datasets and real-world scenarios, \(g_1\) and \(g_2\) might not exist. The user simply comes in with the complex request \(g_3\). Standard CL methods fail here because they cannot order goals that aren’t there. If you force the agent to train on \(g_3\) immediately, it will fail repeatedly, never receive a reward, and never learn.

The Solution: Bootstrapped Policy Learning (BPL)

The researchers propose a framework that acts as both a teacher and a student. As the policy tries and fails to interact with users, the BPL framework observes these interactions and modifies the goals to match the agent’s current skill level.

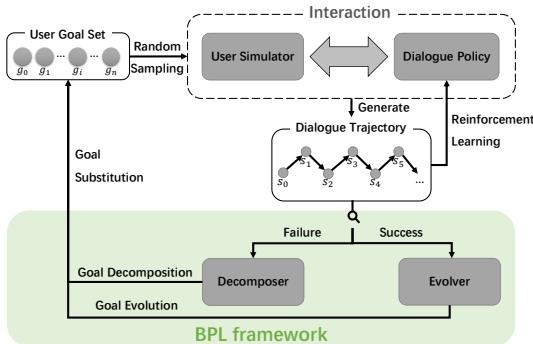

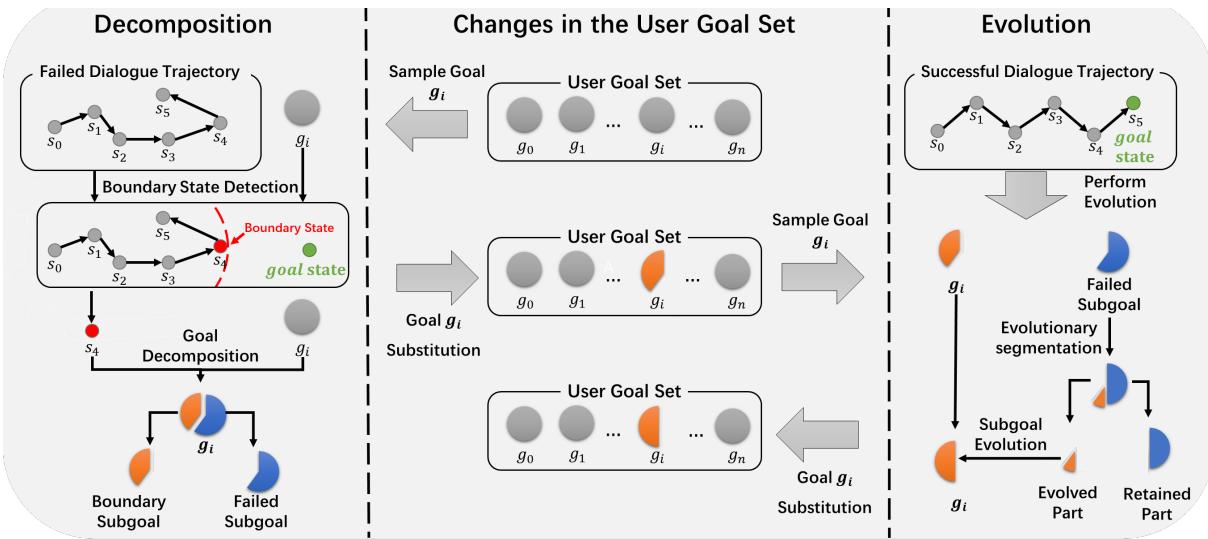

As shown in Figure 1 above, the BPL framework sits inside the training loop. It consists of two distinct mechanisms:

- The Decomposer: Activates when the agent fails. It breaks the complex goal down into a simpler subgoal that the agent did manage to achieve (or came close to).

- The Evolver: Activates when the agent succeeds. It takes a mastered subgoal and re-introduces the complexity, evolving the goal back toward the original difficult task.

This cycle creates a “Bootstrapped” curriculum—one that generates itself based on the agent’s own performance.

Core Method: How Goal Shaping Works

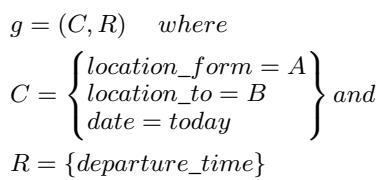

The core of this paper is Goal Shaping. To understand how the Decomposer and Evolver work, we first need to define how the system views a “User Goal.”

Defining the Goal

A user goal isn’t just a sentence; it’s a collection of data points. It typically consists of Constraints (\(C\)) (information the user gives, like “I want to leave from New York”) and Requests (\(R\)) (information the user wants, like “What is the departure time?”).

The difficulty of a goal is roughly equivalent to the total number of slots involved (\(|C| + |R|\)). The more slots, the harder the conversation.

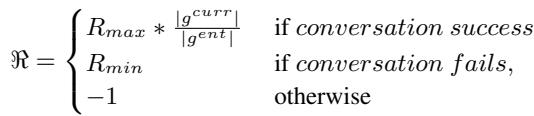

To motivate the agent to complete the entire goal rather than just the easy parts, the authors use a shaped reward function:

This equation ensures that if the agent only completes a subgoal (\(g^{curr}\)), it receives a reward proportional to how much of the full goal (\(g^{ent}\)) that subgoal represents. This prevents the agent from becoming lazy and settling for partial success.

The Mechanism of Decomposition and Evolution

The visual representation of how a goal changes during training is essential for understanding BPL.

1. The Decomposer (Handling Failure)

Let’s look at the left side of Figure 2. Imagine the user wants a taxi (Goals: Destination, Departure Time, Num Passengers). The agent starts talking. It successfully negotiates the Destination and Departure Time (states \(s_0\) to \(s_3\)) but crashes and burns when trying to handle Num Passengers (state \(s_4\)).

The Decomposer analyzes this failed trajectory. It identifies \(s_3\) as the Boundary State—the last point where the conversation was going well.

- It takes the original goal and strips away the parts the agent failed at.

- It creates a Boundary Subgoal (just Destination + Departure Time) and substitutes the original goal with this easier version.

- The agent is now “successful” at this new, simpler task, which provides a positive reward signal and stabilizes learning.

2. The Evolver (Handling Success)

Now look at the right side of Figure 2. Once the agent consistently succeeds at the Boundary Subgoal, the Evolver kicks in. It doesn’t want the agent to stay at this easy level.

- It looks at the Failed Subgoal (the parts we removed earlier).

- It performs Evolutionary Segmentation. It takes a chunk of that failed part (the “Evolved Part”) and adds it back to the current goal.

- The goal becomes slightly harder. If the agent succeeds again, the Evolver adds more chunks until the original complex goal is restored.

Strategies for Shaping

The authors didn’t just pick one way to do this; they explored several strategies for when to decompose and how to evolve.

Decomposition Conditions:

- Failure at any time (A): If you fail, decompose immediately.

- Time-based (T): Only decompose if the agent has been failing for \(N\) epochs (giving it time to try first).

- Consecutive Failure (C): Decompose only if the agent fails the same goal \(M\) times in a row.

Evolution Strategies:

- Fixed (F): Add exactly one slot back at a time. (Slow and steady).

- Reward Control (R): Add slots based on how high the reward was. (If you aced the test, you get a much harder test next).

- Exploration (E): Add slots based on the “state differential space”—a metric measuring how well the agent has explored the environment.

Experiments and Results

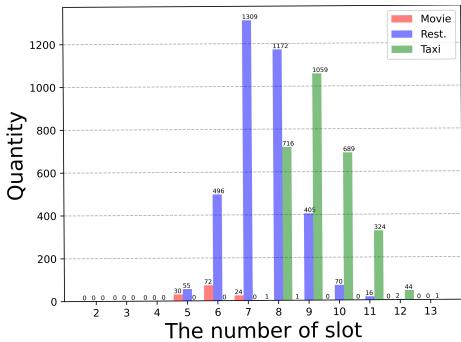

To validate BPL, the researchers tested it on four datasets with varying difficulty levels: Movie (Simple), Restaurant (Medium), Taxi (Hard), and the famous MultiWOZ 2.1 (Very Hard, multi-domain).

As shown in the slot distribution graph below, the datasets have distinct difficulty curves. The “Taxi” domain, for instance, requires handling many more slots on average than the “Movie” domain.

Comparison with Baselines

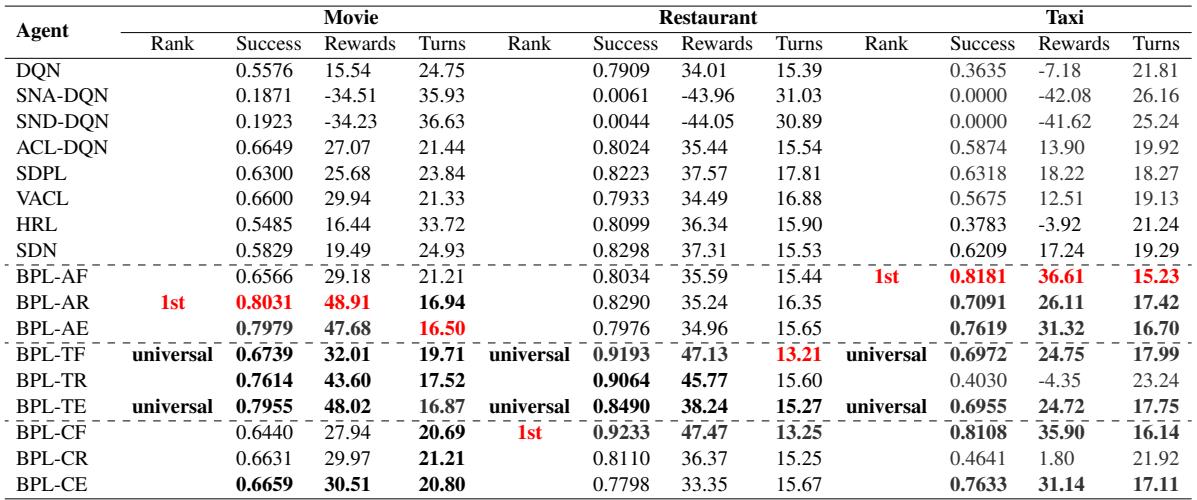

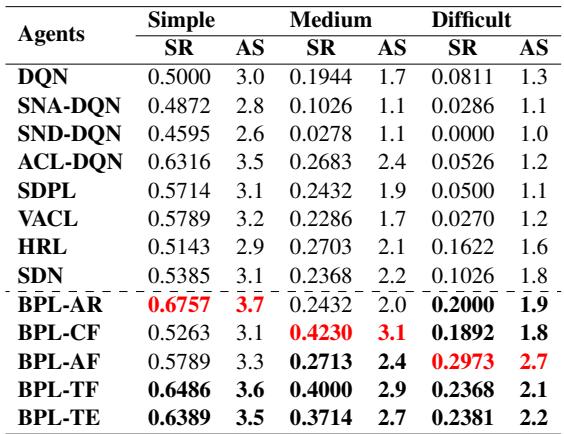

The authors compared BPL against standard Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and several state-of-the-art Curriculum Learning methods (like SNA-DQN, SDPL, and VACL).

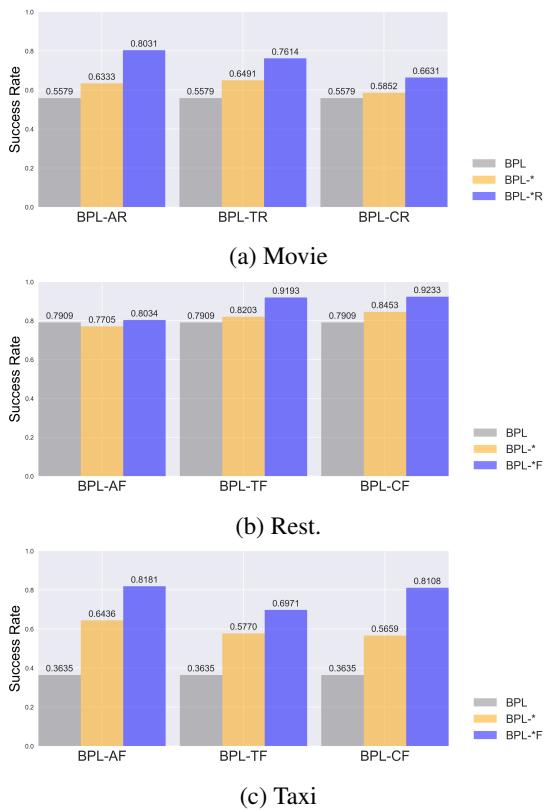

The results, summarized in Table 2, are compelling.

Key Takeaways from the Results:

- BPL Dominates: In almost every category (Success Rate, Rewards), a variant of BPL outperforms the baselines.

- Difficulty Matters:

- On the Simple (Movie) dataset, BPL-AR (Always decompose, Reward-based evolution) worked best. Why? Because the tasks are easy, so the agent can afford to be aggressive (fast evolution).

- On the Hard (Taxi) dataset, BPL-AF (Always decompose, Fixed evolution) was superior. Hard tasks require patience—adding just one slot at a time (Fixed) prevents the agent from getting overwhelmed.

- Universal Patterns: The researchers identified BPL-TF and BPL-TE as “Universal” patterns. These use a Time-based trigger (wait a bit before simplifying) and Fixed or Exploration-based evolution. These combinations were robust across all datasets, making them a safe bet for unknown environments.

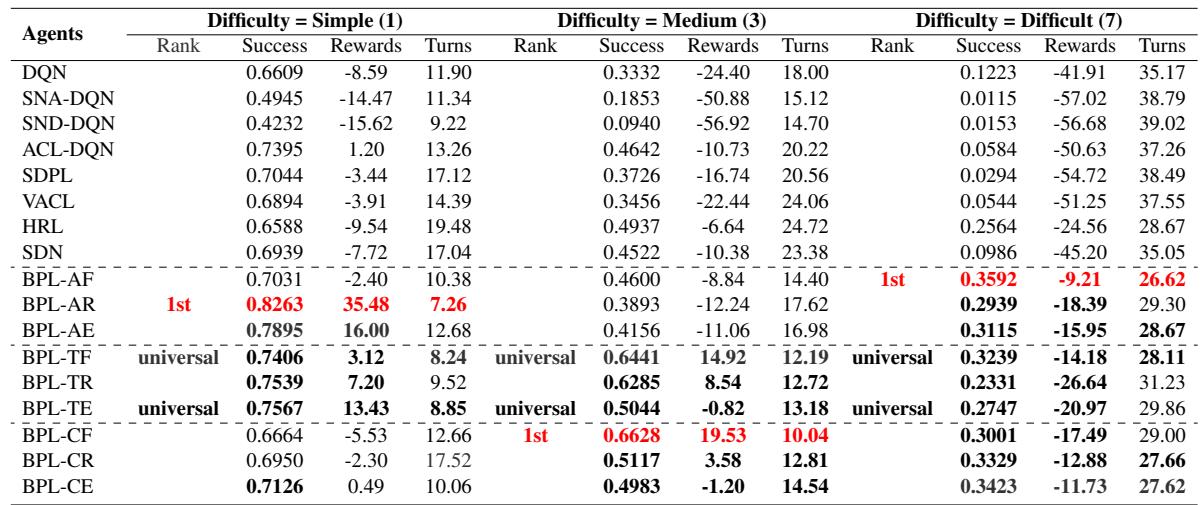

Multi-Domain Performance (MultiWOZ)

The real test of any dialogue system is MultiWOZ, which involves jumping between domains (e.g., booking a train and then finding a restaurant).

Table 4 confirms the trend. The BPL variants (specifically the universal ones like BPL-TF) maintain high success rates even as the difficulty (size) of the domains increases. Standard DQN and even some advanced CL methods struggle significantly here because the “jump” in complexity is simply too high without intermediate subgoals.

Why does it work? (Ablation Study)

Is it the Decomposer or the Evolver that does the heavy lifting? The authors performed an ablation study to find out.

In Figure 6, the gray bars (BPL) represent the full system, while the colored bars show versions with components removed or altered.

- Decomposition is Vital: In hard datasets (like Taxi, graph ‘c’), the Decomposer (which simplifies tasks) is crucial. Without it, the agent hits a wall.

- Evolution adds Efficiency: While decomposition prevents total failure, the Evolver ensures the agent actually progresses back to the hard tasks efficiently.

Human Evaluation

Simulations are great, but do humans actually prefer talking to BPL agents? The authors conducted a study with 98 participants.

The human evaluation (Table 5) aligns with the simulation. BPL agents achieved higher Success Rates (SR) and Average Scores (AS) for naturalness and coherence compared to baselines.

Conclusion

The Bootstrapped Policy Learning framework represents a significant shift in how we train task-oriented dialogue systems. Instead of relying on a human-curated curriculum or hoping the agent gets lucky with sparse rewards, BPL empowers the agent to tailor the learning process to its own current capabilities.

By treating failure not as a dead-end but as a source of data for generating subgoals (Decomposition), and treating success as an invitation to increase complexity (Evolution), BPL ensures a smooth knowledge transition. This effectively fills in the missing rungs of the ladder, allowing AI to climb from simple interactions to complex, multi-domain conversations.

Key Takeaways:

- No Pre-set Curriculum: BPL generates the curriculum dynamically during training.

- Goal Shaping: The combination of breaking down goals (Decomposition) and rebuilding them (Evolution) solves the sparse reward problem.

- Versatility: Specific configurations (like BPL-TF) work universally well, regardless of the specific dataset difficulty.

For students and researchers in RL and NLP, this paper underscores the importance of adaptive training. It suggests that the future of robust AI might not lie in better datasets, but in better ways for agents to practice on the data we already have.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2807/images/cover.png)