The scale of Large Language Models (LLMs) is exploding. From GPT-4 to Llama, models are getting bigger, smarter, and—crucially—much more expensive to run. The primary culprit for this cost is the dense nature of these architectures: every time you ask a question, every single parameter in the model is activated to calculate the answer.

Imagine a library where, to answer a single question, the librarian has to open and read every single book on the shelves. That is a dense model.

A more efficient alternative is the Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture. In an MoE, the model is divided into specialized sub-networks called “experts.” For any given input, the model only activates a tiny fraction of these experts. It’s like the librarian knowing exactly which three books contain the answer and ignoring the rest.

However, there is a catch. Training MoEs from scratch is unstable and difficult. A clever workaround called “MoEfication” allows us to take a standard, pre-trained dense model and convert it into an MoE without expensive retraining. Until recently, this only worked well for models using the ReLU activation function.

In this post, we will dive deep into a research paper that solves this problem: “Breaking ReLU Barrier: Generalized MoEfication for Dense Pretrained Models.” We will explore how the authors developed G-MoEfication, a technique that allows any dense model (using GeLU, SiLU, etc.) to be converted into an efficient, sparse Mixture-of-Experts.

The Problem: The ReLU vs. GeLU Divide

To understand why converting models is hard, we first need to look at activation functions. These are the mathematical gates inside a neural network that decide whether a neuron “fires” or not.

For years, ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) was the standard. ReLU is very simple: if a value is negative, it becomes zero. If it’s positive, it stays the same.

\[ \text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0, x) \]Because ReLU forces all negative values to be exactly zero, ReLU-based neural networks are naturally sparse. Many neurons naturally output zero. This makes it easy to cut them out (turn them off) without changing the model’s output much.

However, modern LLMs (like BERT, GPT, Llama, and Phi) rarely use ReLU anymore. They use smoother variants like GeLU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) or SiLU. These functions are better for training stability, but they have a major downside for our purposes: they are almost never exactly zero.

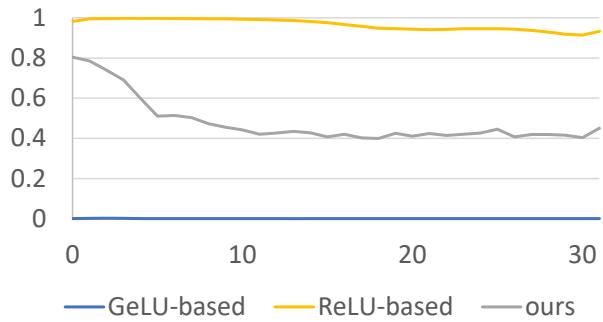

As shown in Figure 1, the orange line represents a ReLU-based model, which maintains high sparsity (lots of zeros). The blue line represents a GeLU-based model (Phi-2), which has practically zero sparsity.

If you try to “MoEfy” a GeLU model by treating small values as zero, you destroy information, and the model’s performance collapses. This is the ReLU Barrier.

Background: What is MoEfication?

Before we look at the solution, let’s briefly understand how we convert a dense model into an MoE in the first place.

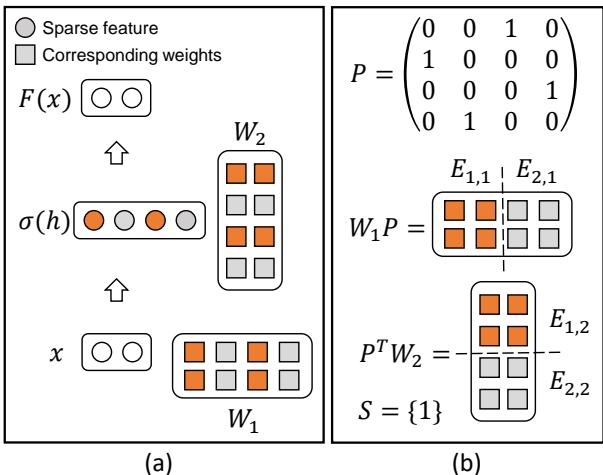

A standard Feed-Forward Network (FFN) layer in a Transformer looks like this:

- Input comes in.

- It gets multiplied by weights (\(W_1\)).

- An activation function (\(\sigma\)) is applied.

- It gets multiplied by output weights (\(W_2\)).

In MoEfication, the goal is to split the neurons in the FFN layer into groups, or “experts.”

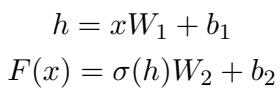

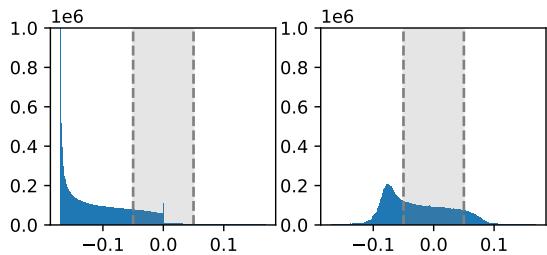

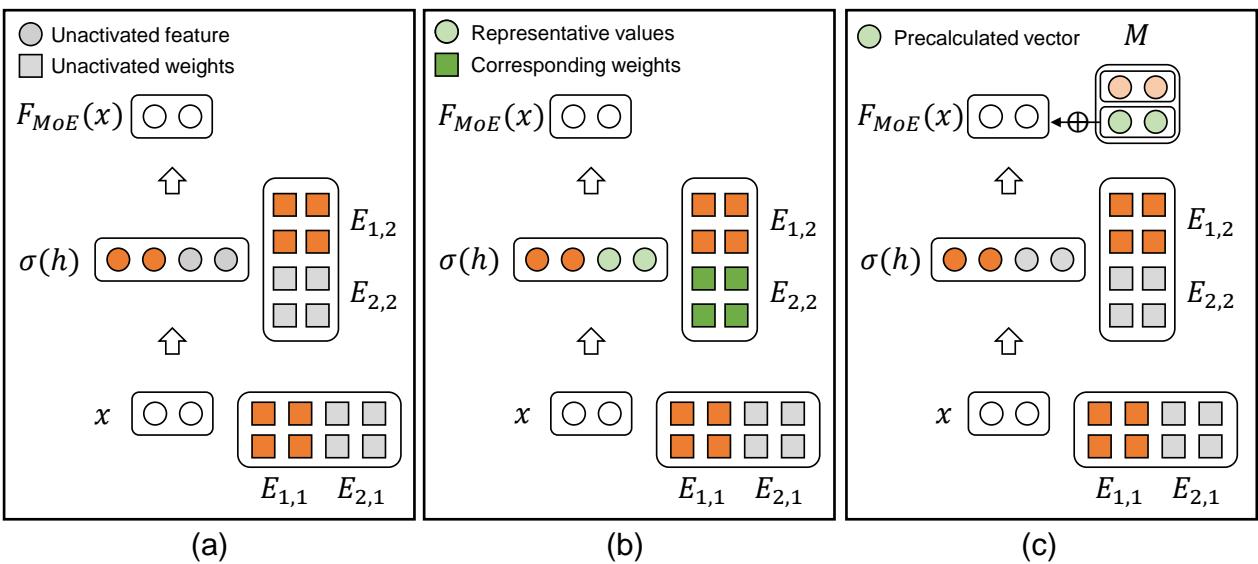

As illustrated in Figure 2, we look for neurons that tend to fire at the same time (the orange dots in panel a) and cluster them together.

- Panel (a) shows how sparse activations (ReLU) leave many neurons unactivated (grey).

- Panel (b) shows how we can group these weights into clusters.

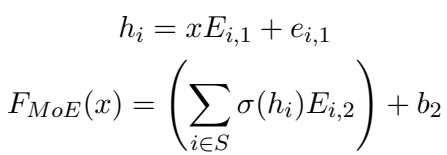

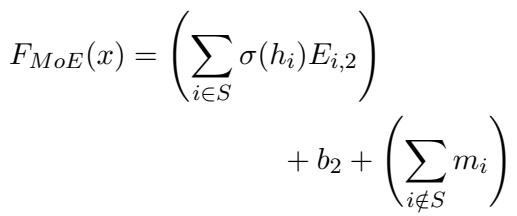

Mathematically, we decompose the large weight matrices into smaller “expert” matrices (\(E_{i,1}, E_{i,2}\)). During inference, a “router” selects only the most relevant experts (\(S\)) to process the input.

The formula above describes the MoE output. Instead of summing over all neurons, we sum only over the selected experts in set \(S\).

The Core Method: G-MoEfication

The researchers propose G-MoEfication (Generalized MoEfication) to handle models where activations are not naturally sparse. They face a dilemma:

- If you treat non-selected experts as zero (like in standard MoE), you lose the information contained in those small, non-zero GeLU activations.

- If you keep calculating them, you don’t save any computational cost.

The solution requires three clever steps: Soft Sparsity, Representative Values, and Static Embeddings.

1. Redefining Sparsity

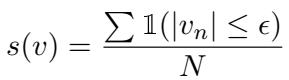

Instead of looking for “hard” zeros, the authors define “soft sparsity.” They consider an activation sparse if it falls within a very small range (\(-\epsilon\) to \(+\epsilon\)) around zero.

This allows us to treat GeLU models as having “sparse” regions, provided we can handle the small residuals effectively.

2. The Representative Value Trick

Here is the key innovation. In a standard MoE, if an expert is not selected, its contribution is set to 0. In G-MoEfication, if an expert is not selected, its contribution is set to a Representative Value (\(r\)).

Look at Figure 4.

- Left: The original distribution of activations in a GeLU model. It’s peaked near zero but not exactly zero.

- Right: The authors propose shifting the distribution. They identify a “representative value” (typically the mean) for each neuron.

By subtracting this representative value, the “residual” (the remaining part) becomes much closer to zero. This minimizes the error when we ignore the specific fluctuations of unselected experts.

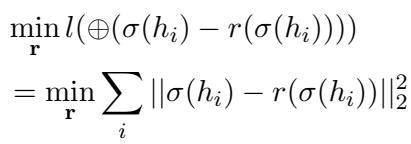

The optimization goal changes from simply minimizing the error of zeroing-out experts to minimizing the error of replacing them with their representatives:

The optimal representative value \(r\) turns out to be simple: it is the mean activation value of that neuron over a sample dataset.

3. The Computational Shortcut (Static Embeddings)

You might be thinking: “Wait, if we have to add a representative value for every unselected expert, aren’t we still doing math for every expert? How does this save time?”

If we naively calculated the representative value contribution for every unselected expert, it would look like Figure 3(b) below—computationally heavy.

- Figure 3(a): Naive MoE just drops information (grey dots). Fast, but inaccurate for GeLU.

- Figure 3(b): Keeping representative values (green dots) preserves info but requires computation.

- Figure 3(c) - The Solution: Because the representative value \(r\) is static (it’s just the mean, it doesn’t change based on input), the result of passing it through the second weight layer (\(W_2\)) is also constant!

The researchers pre-calculate the output of all representative values. They sum these up into a single vector (or embedding).

During inference, the equation becomes:

Here:

- The first term \(\sum_{i \in S} \dots\) is the standard computation for the few selected experts.

- The term \(\sum_{i \notin S} m_i\) represents the contribution of the unselected experts. Since \(m_i\) is pre-calculated, this is just a simple vector addition.

This clever trick allows the model to “hallucinate” the presence of the unselected experts without actually doing the heavy matrix multiplications for them.

Experiments and Results

Does this theory hold up in practice? The researchers tested G-MoEfication on several models, including mBERT (multilingual BERT), SantaCoder, Phi-2, and Falcon-7B.

Performance on mBERT

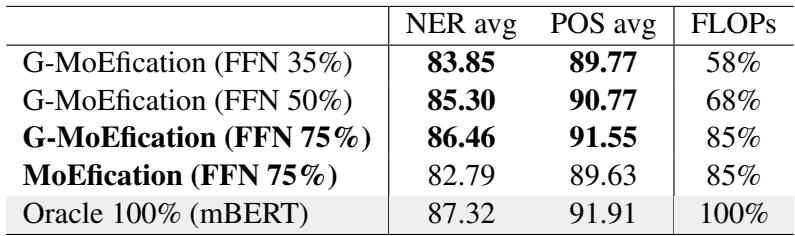

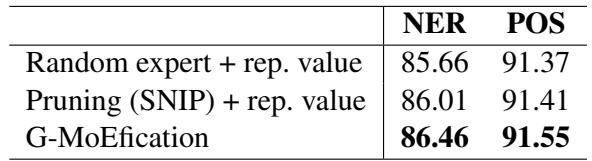

They compared G-MoEfication against standard MoEfication (which assumes hard sparsity) on Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging tasks across 42 languages.

Table 1 shows the results:

- G-MoEfication (FFN 35%) retains about 96-97% of the original model’s performance while using only 58% of the FLOPs (computational operations).

- Crucially, looking at the first column (NER avg), G-MoEfication scores 83.85, significantly beating the standard MoEfication score of 82.79, even though the standard version used more parameters (75%).

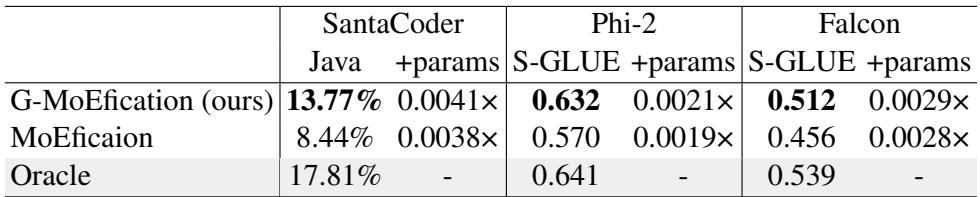

Generative Models (Zero-Shot)

One major concern with MoEfication is whether it breaks the delicate capabilities of generative models. The authors applied their method to Phi-2 and Falcon-7B without any fine-tuning (zero-shot evaluation).

As seen in Table 2:

- Phi-2: The original model scores 0.641 on SuperGLUE. G-MoEfication achieves 0.632—a negligible drop. Standard MoEfication drops significantly to 0.570.

- SantaCoder: On code generation (Java), G-MoEfication achieves 13.77%, far outperforming the 8.44% of standard MoEfication.

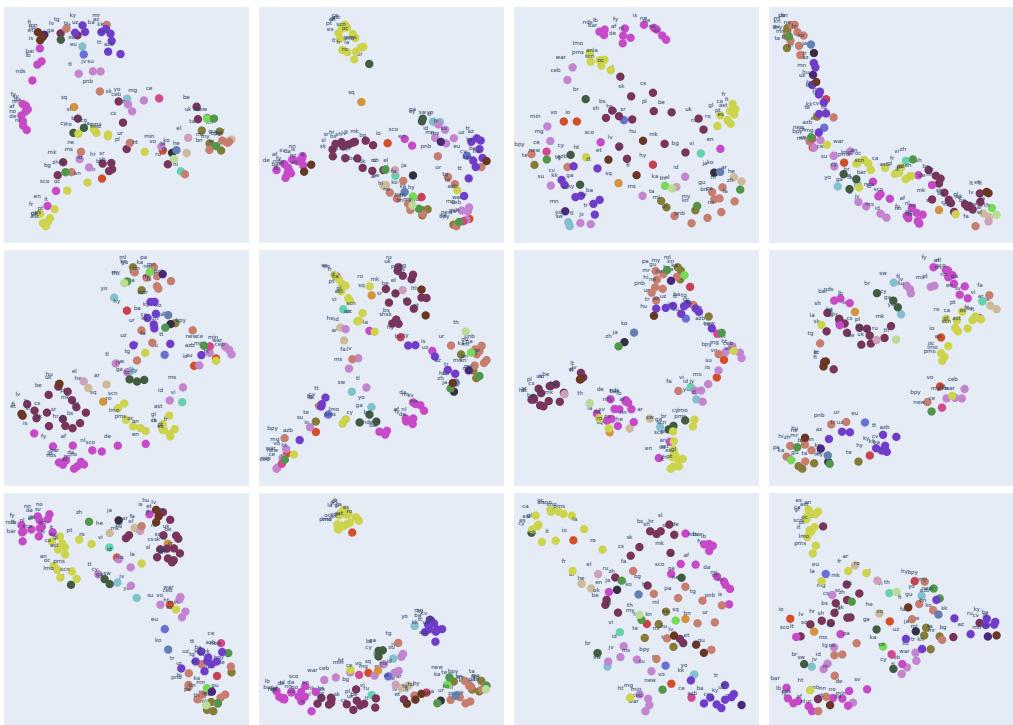

Visualizing the Experts

One fascinating aspect of MoEs is “expert specialization.” Do specific experts actually learn specific concepts?

The researchers visualized the expert selection patterns for the multilingual mBERT model.

Figure 5 projects the expert usage patterns for 103 different languages. The colors represent language families (e.g., Germanic, Romance, Slavic). The clustering is clearly visible: the model automatically routes French, Spanish, and Italian to similar experts, while routing Chinese and Japanese to others. This confirms that the MoEfication process preserves the semantic structure of the dense model.

Computational Efficiency

Finally, it is worth verifying if the “static vector” trick actually saves time.

Table 3 (below) compares the parameter selection methods.

The table shows that their trained expert selection outperforms random selection and pruning (SNIP). Furthermore, the paper notes that using the static vector design reduces FLOPs to 58% of the original mBERT. Without the static vector trick (calculating representatives on the fly), the FLOPs would actually increase to 101%. The pre-calculation is essential.

Conclusion and Implications

The “ReLU Barrier” has long prevented the efficient deployment of modern, dense Transformers as Mixtures-of-Experts. G-MoEfication provides an elegant mathematical solution to this problem.

By realizing that “zeroing out” is not the only way to save compute, and by utilizing representative values stored as static embeddings, the authors have unlocked a path to compress and speed up virtually any modern LLM.

Key Takeaways:

- Generalized approach: Works on GeLU, SiLU, and other non-sparse activations.

- No Pre-training: Converts existing checkpoints directly.

- Preserves Information: Uses mean statistics to approximate unselected experts rather than deleting them.

- High Efficiency: Converts heavy matrix math into lightweight vector addition.

As models continue to grow, techniques like G-MoEfication will be vital in making them accessible, faster, and greener to run on standard hardware.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2809/images/cover.png)