Food is perhaps the most universal language we have, yet it is deeply fragmented by dialects of culture, geography, and history. If you have ever tried to recreate a specific dish from a foreign cuisine using locally available ingredients, you know the struggle. It is not merely a translation problem; it is a cultural adaptation problem.

Directly translating a Chinese recipe into English often results in confusion. “Moderate amount of ginger” is vague to a Western cook used to teaspoons and cups. Ingredients like “rice wine” might not be on the shelf at your local grocery store.

In the age of Large Language Models (LLMs), the temptation is to simply ask GPT-4 to “translate and adapt this recipe.” However, a recent paper titled “Bridging Cultures in the Kitchen” by researchers from the University of Copenhagen argues that generative AI often misses the mark. They propose a different approach: Cross-Cultural Recipe Retrieval.

Instead of asking an AI to invent a new English version of a Chinese dish (which often leads to culinary hallucinations), why not use AI to find the closest existing recipe written by a human in the target culture?

In this deep dive, we will explore the CARROT framework, understand why food translation is so difficult, and look at a new benchmark that proves why retrieving real recipes is often safer—and tastier—than generating them.

The Problem: When Translation Loses the Flavor

Imagine you want to make Red Bean Soup (红豆汤). You have a Chinese recipe, but you need an English version that matches your kitchen’s inventory.

If you use a standard machine translation, you get a literal list of ingredients. If you use a powerful generative model like GPT-4, it attempts to adapt the recipe. It might convert grams to cups, which is helpful. But it also might make strange decisions.

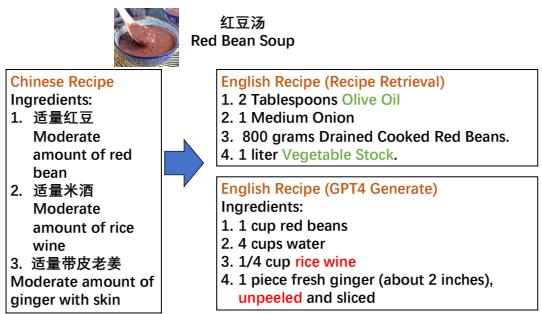

Take a look at the example below.

As shown in Figure 1, the “Chinese Recipe” calls for red beans, rice wine, and ginger with skin.

The GPT-4 Generated version (bottom right) is linguistically fluent but culturally confused. It suggests “1/4 cup rice wine” and “unpeeled ginger.” In English-speaking culinary culture, using unpeeled ginger in a soup is rare, and rice wine is not a standard pantry staple for a typical Western dessert soup.

However, look at the English Recipe (Recipe Retrieval) in the top right. This isn’t a translation; it is an existing recipe found in an English database. It calls for “Olive Oil,” “Onion,” and “Vegetable Stock.” Wait, onions in red bean soup? Yes. In Western cuisine, red bean soup is often a savory dish (like a bean stew), whereas in China, it is a sweet dessert.

This highlights the core tension: What counts as a “match”?

- Exact Translation: Keeps the sweet profile but demands ingredients the user might not have or understand.

- Cultural Adaptation: Finds a dish the target audience actually cooks (savory bean soup) that utilizes the main ingredient (red beans).

The researchers argue that for true cultural adaptation, we need a system that understands these nuances. The goal isn’t just to translate words; it is to bridge the gap between “what I have” and “how you cook.”

The Semantic Gap in the Kitchen

The paper identifies three major challenges that make this task harder than standard Google searching.

1. Naming Conventions

In English, recipes are usually descriptive: “Roast Chicken with Lemon.” In Chinese, names can be poetic, historical, or obscure.

- “Ants Climbing a Tree” is a glass noodle dish with minced meat, not an insect snack.

- “Lion’s Head” is a giant meatball, not a zoo animal. A standard search engine looking for “Lion” will fail to find the correct meatball recipe in an English database.

2. Ingredient Availability

A “Stir-fried Taro” recipe needs to be adapted. If taro isn’t available, is a potato a valid substitute? A retrieval system needs to know that these two root vegetables fill a similar culinary niche.

3. Food Common Sense

Recipes often omit what is considered “common knowledge” in their native culture. A Chinese recipe might say “add three fresh ingredients,” assuming the reader knows this refers to a specific combo of potatoes, eggplants, and peppers. An outsider would be lost.

Introducing CARROT: Cultural-Aware Recipe Retrieval

To solve these problems, the authors propose CARROT (Cultural-Aware Recipe Retrieval Tool).

CARROT is a “plug-and-play” framework. It doesn’t require training a massive new AI model from scratch. Instead, it cleverly combines Large Language Models (LLMs) for their reasoning capabilities with Information Retrieval (IR) for their ability to find ground-truth documents.

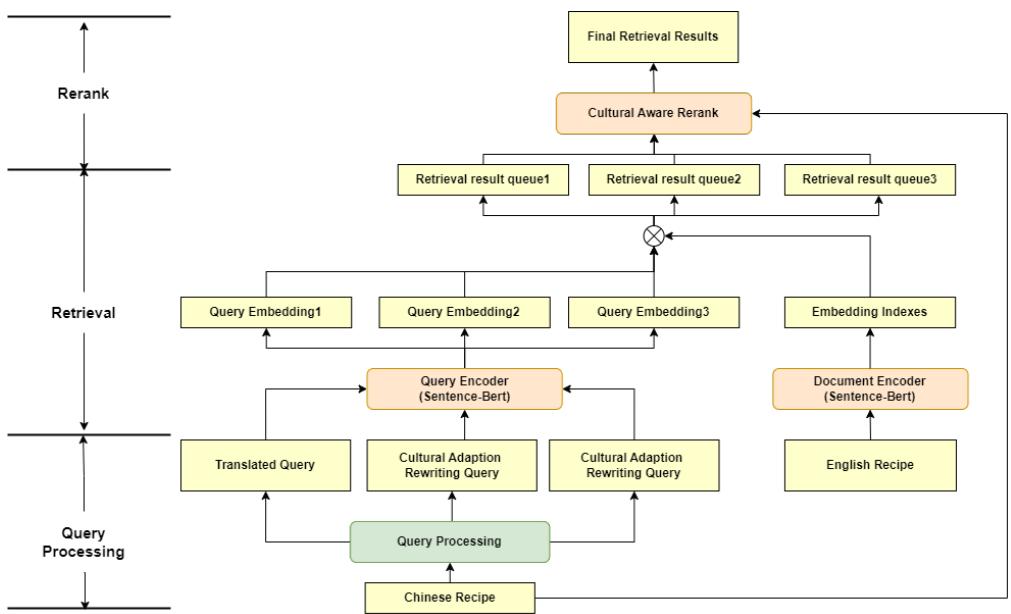

The framework operates in three distinct stages, as visualized below.

Stage 1: Query Processing (The “Rewrite”)

The process starts with a Chinese recipe (the “Query”). If we just translated the title, we would fail (remember “Lion’s Head”).

CARROT uses an LLM (like Llama-3) to perform Cultural Adaptation Rewriting. It looks at the ingredients and cooking steps of the source recipe and generates a new, descriptive English title.

- Input: A complex Chinese recipe for “Husband and Wife Lung Slices.”

- Rewritten Query: “Spicy Beef and Tripe Salad.”

This rewritten query is much more likely to match recipes in an English database.

Stage 2: Retrieval (The Search)

The system then takes this new query and searches through a massive database of English recipes (using a bi-encoder model like Sentence-BERT). It retrieves a “candidate pool”—perhaps the top 100 recipes that seem relevant.

Stage 3: Cultural-Aware Reranking (The Filter)

This is the most innovative part. Standard search engines rank results by how many keywords match. CARROT goes a step further.

It feeds the candidate recipes back into an LLM with a specific prompt: “Rank these recipes based on relevance, but prioritize those that align with the target culture’s habits.”

This step filters out recipes that might be textually similar but culturally weird (like the sweet soup vs. savory stew issue), pushing the most culturally appropriate, cookable recipes to the top.

Why “Rewriting” is the Secret Sauce

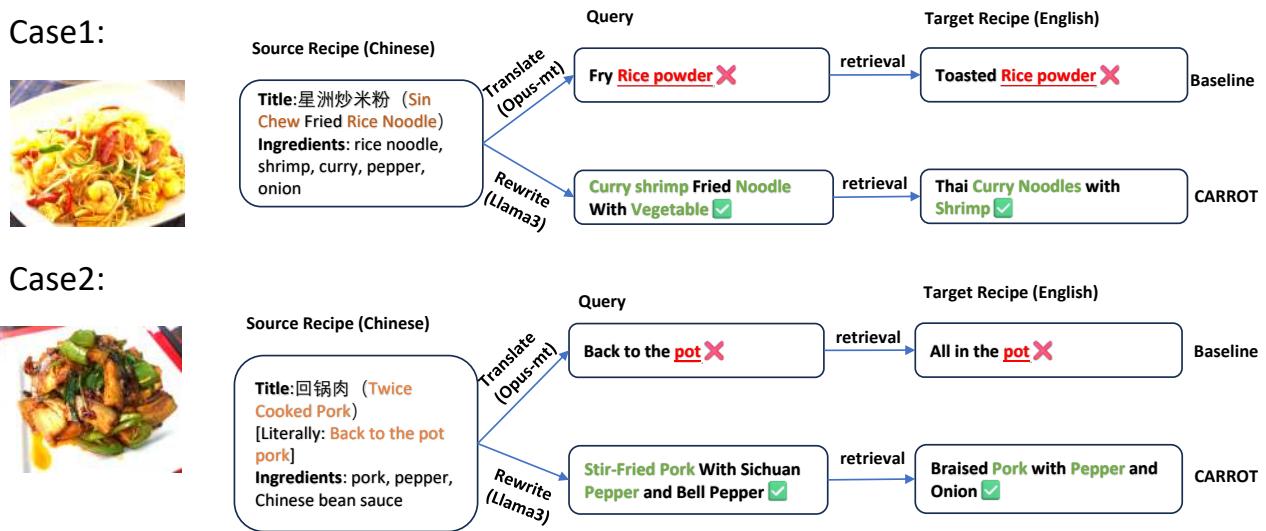

To understand why CARROT works better than basic translation, we need to look at specific examples where direct translation fails.

Case 1: “Sin Chew Fried Rice Noodle”

- The Translation Trap: The literal translation converts “Rice Noodle” to “Rice Powder.” Searching for “Fry Rice Powder” gives you “Toasted Rice Powder”—a completely different ingredient.

- The CARROT Fix: The model analyzes the ingredients (Curry, Shrimp, Noodles) and rewrites the query to “Curry Shrimp Fried Noodle.” This successfully retrieves a “Thai Curry Noodles” recipe. It’s not identical, but it’s a culturally relevant, cookable match.

Case 2: “Twice Cooked Pork”

- The Translation Trap: The Chinese name (回锅肉) literally means “Back to the Pot Meat.” A search engine looks for “Back to the Pot” and finds nonsense like “All in the pot.”

- The CARROT Fix: The rewrite generates “Stir-Fried Pork With Sichuan Pepper,” which correctly retrieves a “Braised Pork with Pepper” recipe.

Building the Benchmark

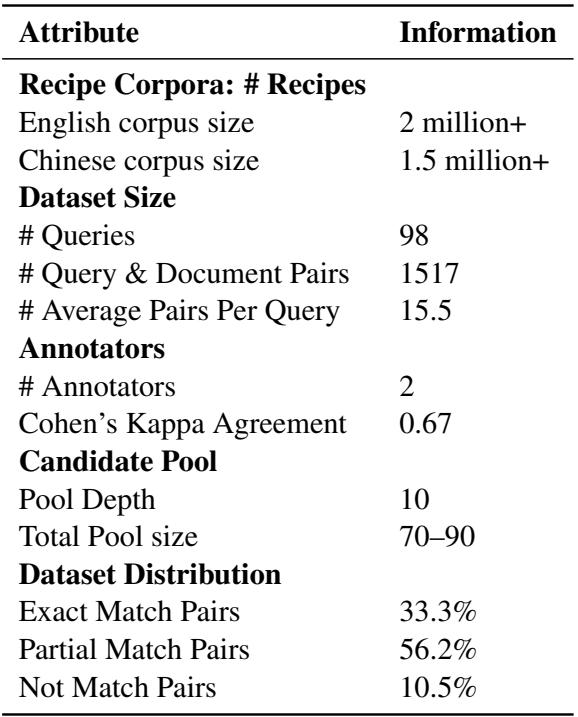

One of the biggest hurdles in this research was the lack of data. There was no existing dataset that paired Chinese recipes with their culturally adapted English equivalents for retrieval purposes.

The authors built a new benchmark using two massive recipe corpora: XiaChuFang (1.5 million Chinese recipes) and RecipeNLG (2 million English recipes).

Because they couldn’t manually check millions of pairs, they used a pooling strategy. They used various retrieval methods to find the top candidates for a set of queries and then had bilingual human annotators judge the relevance of these pairs.

As shown in Table 1, the resulting dataset is compact but high-quality. It contains 98 diverse queries and over 1,500 annotated pairs. Interestingly, only 33.3% of the pairs were “Exact Matches,” highlighting how difficult it is to find a 1:1 equivalent of a dish across cultures.

Experiments: Generation vs. Retrieval

So, which is better? Asking an AI to write a recipe (Generation) or asking it to find one (Retrieval)?

The researchers evaluated both approaches using metrics like BLEU (how much the text overlaps) and Human Evaluation (judging grammar, consistency, and cultural appropriateness).

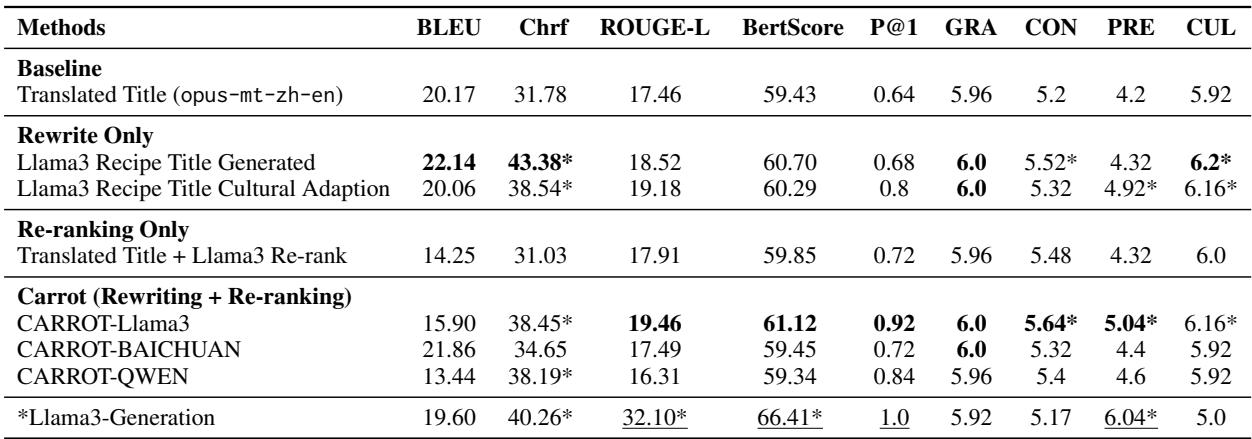

The results in Table 3 (below) reveal a fascinating trade-off.

The “Generation” Illusion

Look at the Llama3-Generation row at the bottom. It scores highest on ROUGE-L and BERTScore. This means the AI is very good at writing text that looks like the reference recipe.

However, high textual similarity doesn’t mean the recipe works.

The “Retrieval” Reality

Now look at the CARROT-Llama3 row (under “Carrot”). While it has slightly lower textual overlap scores, it wins where it counts:

- CON (Consistency): 5.64 vs 5.17.

- CUL (Cultural Appropriateness): 6.16 vs 5.0.

Why does Retrieval win on Consistency?

The authors note a critical flaw in Generative AI: Hallucination in Logic. For example, in a generated recipe for “Braised Beef,” Llama-3 wrote:

“Cover for 1 hour… Remove the pot from the heat and discard.”

It told the user to throw away the food they just cooked!

Because CARROT retrieves recipes written by humans, they are logically sound. A human didn’t write a recipe that tells you to throw the beef in the trash. The retrieval method ensures that the cooking steps actually result in an edible dish.

Why does Retrieval win on Culture?

Generative models tend to be conservative—they keep the original ingredients even if they don’t fit the new culture (like the unpeeled ginger). Retrieval models, by definition, find recipes that already exist in the target culture. If the search engine finds a “Salted Chicken” recipe in the US database, it likely includes lemon and thyme—flavors that Western palates expect—rather than just salt and MSG.

Conclusion: The Chef vs. The Librarian

The CARROT framework teaches us an important lesson about the current state of AI. While Large Language Models are incredible creative engines, they lack “grounding.” In domains like cooking, where chemistry and physics matter (you can’t un-burn a stew), purely creative generation is risky.

By using LLMs as Librarians (rewriting queries and ranking results) rather than Chefs (creating recipes from scratch), we get the best of both worlds:

- We bridge the language gap.

- We ensure the recipe is physically possible to cook (Consistency).

- We ensure the flavor profile fits the local palate (Cultural Appropriateness).

This research goes beyond just food. The principles of Cross-Cultural Retrieval could apply to everything from medical advice to technical manuals—anywhere that “translation” requires adapting to a new environment, not just swapping words.

So, the next time you want to cook an exotic dish, don’t just ask a chatbot to invent a recipe. Use tools that help you discover how the locals actually cook it. Your dinner guests will thank you.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2811/images/cover.png)