In the fast-paced world of Artificial Intelligence, we often marvel at Large Language Models (LLMs) that can write poetry in English, debug code in Python, or translate French to German with near-human accuracy. However, this technological revolution is not evenly distributed. For billions of people, the digital world remains largely inaccessible in their native tongues.

This is the challenge of Low-Resource Languages—languages that lack the massive digital text archives required to train modern AI systems.

Today, we are diving deep into a significant step forward for Emakhuwa, a Bantu language spoken by roughly 25% of Mozambique’s population. Despite being the country’s most widely spoken indigenous language, Emakhuwa has historically been invisible to the NLP community. A recent research paper, “Building Resources for Emakhuwa,” aims to change that. The researchers have built the first substantial datasets and benchmarks for Emakhuwa, tackling two critical tasks: Machine Translation (MT) and News Topic Classification.

In this post, we will explore how they collected this data, the unique linguistic challenges they faced, and how state-of-the-art models perform when tasked with learning this complex African language.

The Emakhuwa Context

Before we look at the algorithms, we need to understand the language. Emakhuwa is spoken in northern and central Mozambique. It is an agglutinative language, meaning words are formed by stringing together various morphemes (small meaningful units). This results in long, complex words that can convey what would require a whole sentence in English or Portuguese.

Furthermore, Emakhuwa has tonal attributes and a spelling system that is not yet fully standardized. These features make it particularly difficult for standard NLP models, which often rely on consistent spelling and shorter word forms found in languages like English.

Until now, if you wanted to build a translation app for Emakhuwa, you would hit a wall: the data simply didn’t exist.

Part 1: The Hunt for Data

The core contribution of this paper is the creation of a “full stack” of resources. The researchers didn’t just scrape the web; they employed a multi-pronged strategy to gather high-quality text.

1. The “Gold Standard”: Parallel News Corpus

The researchers created the first parallel news corpus between Portuguese (the official language of Mozambique) and Emakhuwa. This wasn’t done by AI; it was done by humans.

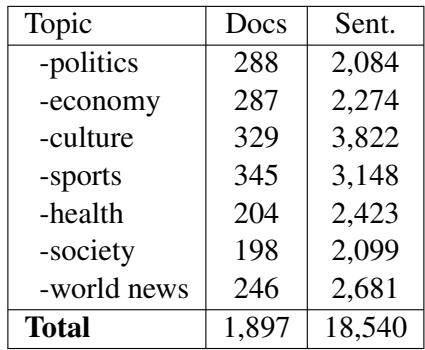

They selected nearly 1,900 news articles covering politics, economy, culture, and sports. They then hired professional translators to convert these articles from Portuguese into Emakhuwa. This resulted in over 18,000 high-quality parallel sentences.

As shown in Table 1 above, the dataset covers a diverse range of topics. This diversity is crucial because a model trained only on “Politics” might fail spectacularly when trying to translate a sentence about “Health” or “Sports.”

2. Rescuing Data via OCR

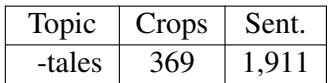

A major issue for low-resource languages is that much of their literature exists only in physical books, not on the internet. To address this, the team digitized the book Método Macua, a text rich in cultural narratives and tales.

They used Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to scan the book, followed by a manual correction phase where volunteers fixed scanning errors.

Table 2 highlights this effort. While the volume (1,911 sentences) is smaller than the news corpus, this data is linguistically unique. It captures traditional narratives and dialogues, which differ significantly from the formal tone of news reports.

3. Monolingual Data

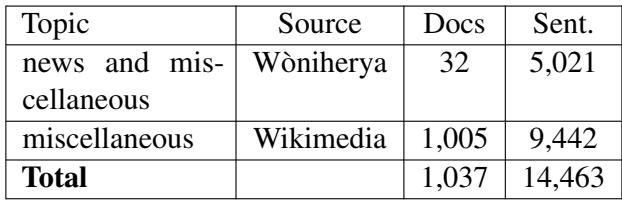

Finally, to understand the structure of a language, models need to read a lot of it, even if there isn’t a translation available. The researchers scraped online magazines and the Emakhuwa Wikimedia incubator to gather purely Emakhuwa text.

Table 3 details this collection. While 14,000 sentences might seem small compared to English datasets (which are in the billions), for a low-resource language, every sentence counts. This data is vital for “back-translation,” a technique we will discuss later.

The Final Dataset Ecosystem

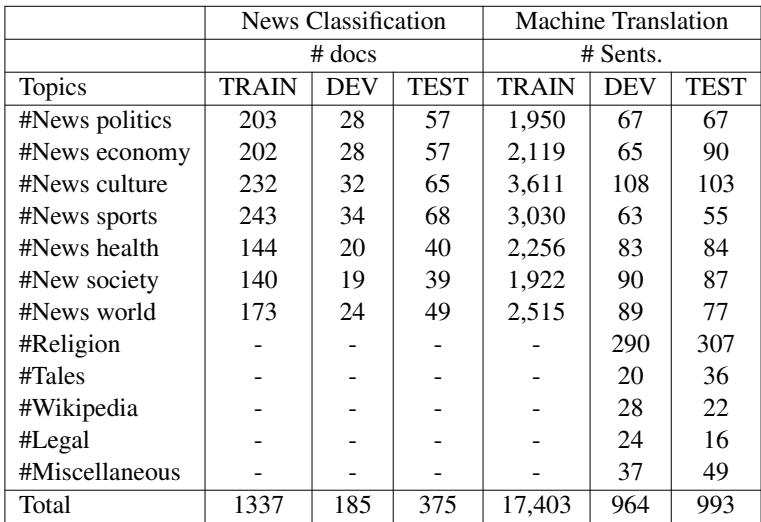

After cleaning and processing, the researchers organized their data into Training, Validation (Dev), and Test sets. This rigorous split ensures that when they evaluate their models, they are testing them on text the models have never seen before.

Table 4 provides the roadmap of the final datasets. Note the specific allocation for “News Classification” versus “Machine Translation.” This structured approach allows future researchers to reproduce these results and compete on the same leaderboard.

Part 2: Machine Translation Benchmarks

With the data in hand, the researchers set out to answer a burning question: Can modern multilingual models actually learn Emakhuwa?

They didn’t start from scratch. Instead, they used Transfer Learning. They took massive models pre-trained on hundreds of languages and “fine-tuned” them on their new Emakhuwa dataset. The models included:

- MT5 & mT0: Google’s massive multilingual transformers.

- ByT5: A “token-free” model that processes text byte-by-byte (very useful for languages with complex spelling).

- NLLB (No Language Left Behind): Meta’s cutting-edge translation model.

- M2M-100: A model designed specifically for many-to-many translation.

The Results: Who is the King of Translation?

The evaluation used two main metrics: BLEU (precision of word matches) and ChrF (character-level matching). ChrF is often better for agglutinative languages like Emakhuwa because it gives credit for getting parts of a complex word right, even if the whole word isn’t a perfect match.

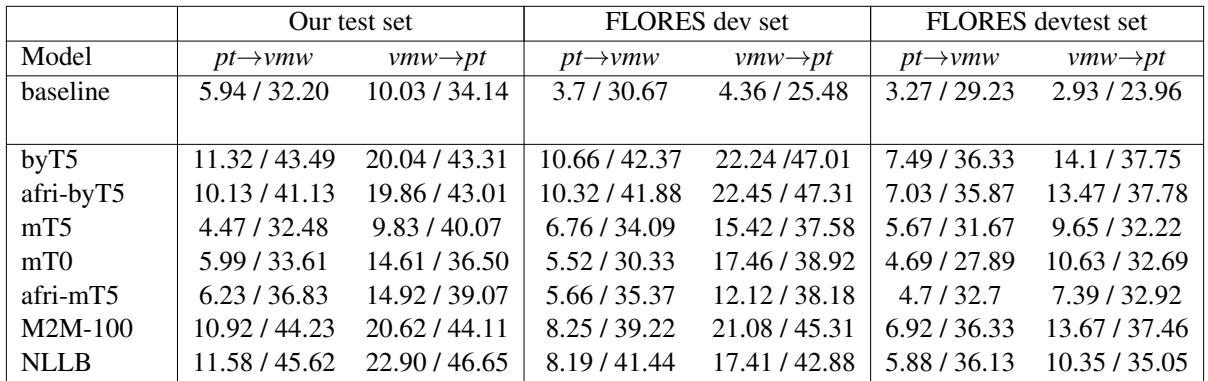

Table 6 reveals the leaderboard. The standouts were NLLB and ByT5.

- NLLB achieved the highest scores, proving that models pre-trained on a massive variety of languages adapt well to new ones.

- ByT5 performed surprisingly well, beating standard mT5. This validates the hypothesis that token-free architectures are superior for languages with rich morphology and spelling variations, as they don’t get tripped up by “unknown” sub-words.

However, notice the gap between the two directions. Translating into Emakhuwa (pt -> vmw) is much harder than translating from it (vmw -> pt). This is expected; generating valid, grammatically complex Emakhuwa words is a tougher generation task than producing Portuguese.

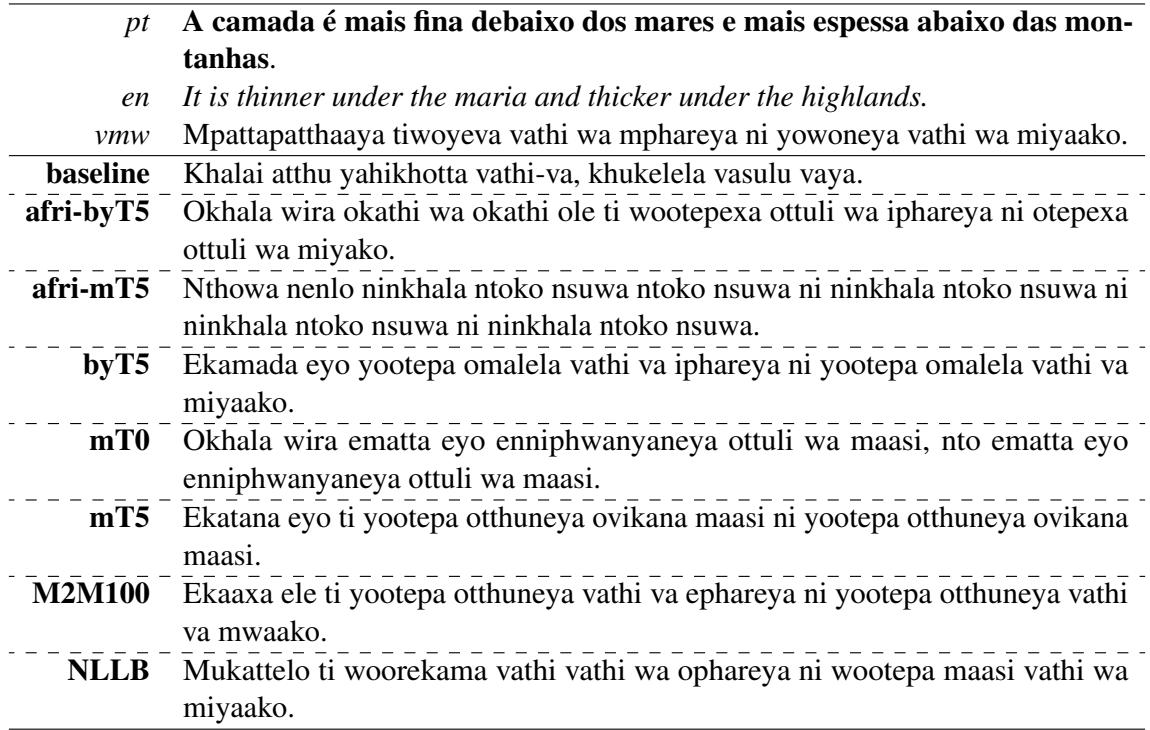

To understand the difficulty, look at Table 10 below. It shows the Portuguese source, the English reference, and the Emakhuwa translation produced by different models.

You can see that the baseline model often hallucinates or produces gibberish. In contrast, NLLB produces a result much closer to the ground truth (“vmw”), though capturing the exact nuance of “thinner under the maria” remains a challenge.

Does More Data Help? (The Data Augmentation Experiment)

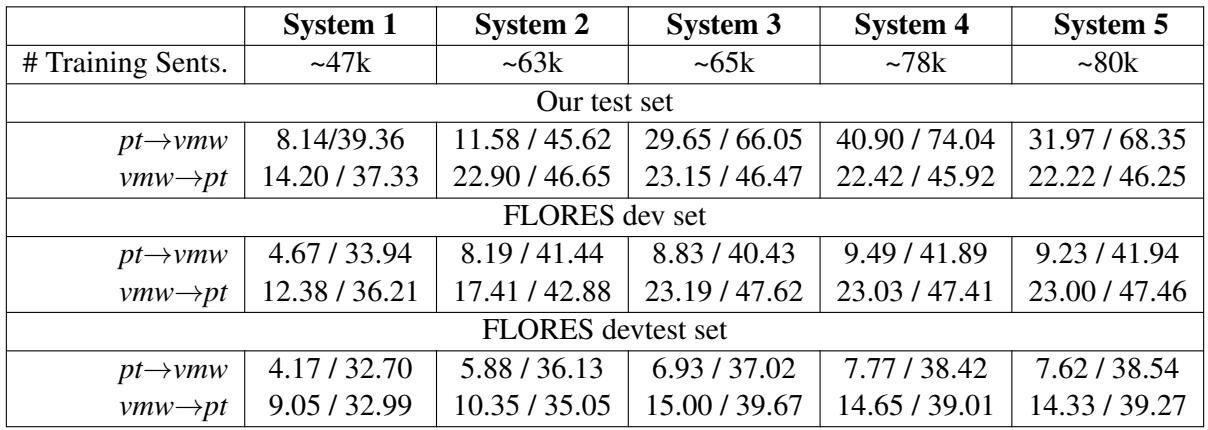

The researchers didn’t stop at simple fine-tuning. They wanted to see if mixing their different data sources would improve performance. They set up a progressive experiment using the NLLB model:

- System 1: Old data only (Ali-2021).

- System 2: Old data + New News Data.

- System 3: All above + OCR Data.

- System 4: All above + Synthetic Data.

Wait, what is Synthetic Data? Using the monolingual text we saw earlier, they trained a model to translate Emakhuwa back into Portuguese. They then treated these machine-generated pairs as training data. This is called Back-Translation.

Table 7 tells a fascinating story.

- News Data acts as a rocket booster: Moving from System 1 to System 2 yielded a massive jump in quality. High-quality human translation is unbeatable.

- Synthetic Data works: System 4 (using back-translated data) provided the best overall performance.

- The OCR Trap: Interestingly, adding the OCR data (System 3) mixed with other sources sometimes hurt performance or provided diminishing returns compared to synthetic data. The researchers hypothesize this is due to Domain Shift. The OCR data is full of folk tales and old idioms, while the test set is modern news. The shift in style likely confused the model.

Part 3: News Topic Classification

The second major task was teaching AI to categorize news articles. Given a headline or a full article, can the model predict if it is about Politics, Sports, Health, or Culture?

The team compared two approaches:

- Classical Machine Learning: Lightweight algorithms like Naive Bayes and XGBoost.

- Fine-Tuned Language Models: Heavyweights like XLM-R, AfriBERTa, and AfroLM.

The “David vs. Goliath” Result

In a surprising twist, the classical Naive Bayes classifier outperformed several complex Deep Learning models, achieving an F1-score of 72.83% when using both Headline and Text.

Why? Many “African-centric” Large Language Models (like AfroLM) were not pre-trained specifically on Emakhuwa. Without that foundational knowledge, their massive neural networks were less effective than a simple statistical approach that just counted word frequencies.

However, the models still struggled with certain categories.

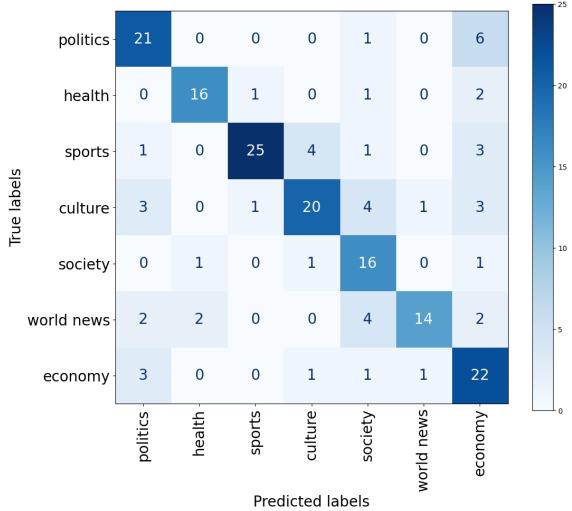

The Confusion Matrix (Figure 1) visualizes these errors.

- Dark Blue Diagonal: The model is very good at identifying Sports (25 correctly classified). The vocabulary of sports (goals, matches, players) is likely very distinct.

- Confusion: Look at the “Politics” and “Economy” sections. There are misclassifications between them. This makes sense—news about the economy often involves government decisions, blurring the lexical line between the two topics. “Society” and “World News” also show significant overlap, likely due to the broad nature of those categories.

Challenges and The Future

While these results are promising, the paper highlights significant limitations that future researchers must address:

- Spelling Inconsistencies: There is no single standard for writing Emakhuwa. One translator might write “Mozambique” as Mosampikhi, while another writes Mocampiiki. This variation confuses models, which see them as completely different words.

- Loanwords: Translators often adapt Portuguese words (like “Governo” for Government) into Emakhuwa phonetically (“Kuveru”) instead of using the native Emakhuwa term. This “lazy translation” pollutes the dataset with Portuguese derivatives.

- Evaluation Metrics: Standard metrics like BLEU penalize the model heavily if it doesn’t match the exact spelling of the reference, which is unfair given the lack of standardized spelling.

Conclusion

This research represents a watershed moment for Emakhuwa in the digital age. By creating the first robust parallel corpora and establishing rigorous benchmarks, the authors have laid the foundation for future innovation.

The key takeaways are clear:

- High-quality human data is irreplaceable. The manually translated news corpus drove the biggest performance gains.

- Multilingual models are powerful, but not magic. NLLB and ByT5 are excellent starting points, but they still struggle without sufficient language-specific data.

- Simpler can be better. For classification, classical algorithms held their own against massive neural networks, proving that we shouldn’t discard traditional methods in low-resource settings.

Most importantly, these resources are now available to the open-source community. This invites students, developers, and linguists to pick up the baton, refine these models, and help ensure that Emakhuwa speakers are not left behind in the AI revolution.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2814/images/cover.png)