Imagine a seasoned physician reviewing a patient’s file. They don’t just look at a list of numbers—blood pressure 140/90, heart rate 100—and statistically calculate the odds of a heart attack. Instead, they engage in clinical reasoning. They synthesize disparate data points, apply external medical knowledge learned over decades, and construct a narrative about the patient’s physiological progression. They might think, “The patient’s creatinine is rising while their blood pressure is unstable, which, given their history of diabetes, suggests acute kidney injury complicating their cardiovascular status.”

Contrast this with traditional Deep Learning models in healthcare. While powerful, they are essentially pattern-matching machines. They ingest massive amounts of Electronic Health Record (EHR) data—diagnostic codes, lab values, timestamps—and output a probability. They are data-driven “black boxes” that often struggle when data is scarce and lack the ability to explain why they made a prediction.

This brings us to a compelling new research paper: CARER (Clinical Reasoning-Enhanced Representation). The researchers behind CARER asked a fundamental question: Can we enhance deep learning models by injecting them with human-like clinical reasoning capabilities generated by Large Language Models (LLMs)?

In this post, we will deconstruct the CARER framework. We will explore how it uses “Chain-of-Thought” prompting to mimic a doctor’s logic, how it aligns raw data with high-level reasoning, and why this approach significantly outperforms state-of-the-art models in health risk prediction.

The Problem: The Limits of Data-Driven Medicine

EHR data is complex and multimodal. It consists of:

- Structured Data: ICD diagnosis codes, demographics, and continuous lab values (like glucose levels).

- Unstructured Data: Clinical notes written by staff.

Standard approaches train separate encoders (like RNNs or Transformers) for these modalities and fuse them. However, these models face three major hurdles:

- Data Inefficiency: They need massive datasets to generalize well. In medicine, high-quality labeled data is often rare or expensive.

- Lack of External Knowledge: A standard model only knows what is in the training set. It doesn’t “know” medical textbooks or pathophysiology unless it learns statistical correlations from scratch.

- The Semantic Gap: There is a disconnect between the “local” view (the raw numbers of a specific patient) and the “global” view (the medical reasoning that explains those numbers).

CARER addresses these by using an LLM not just to read notes, but to actively reason about the patient’s history, effectively acting as an auxiliary “expert” in the loop.

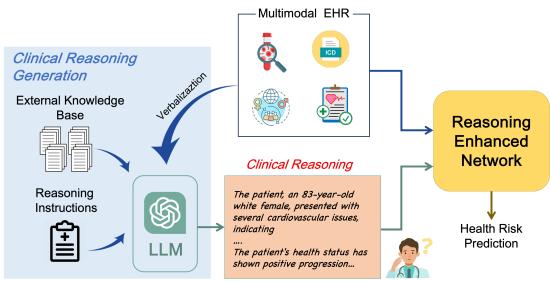

As shown in Figure 1, CARER introduces a dual-pathway system. One path processes the raw EHR data, while the other generates and processes a clinical reasoning narrative. These two paths are then aligned and fused to make a final prediction.

The CARER Framework: A Deep Dive

The architecture of CARER is sophisticated, blending classical deep learning with modern Generative AI techniques. Let’s break it down into three distinct stages: Preparation, Reasoning, and Alignment.

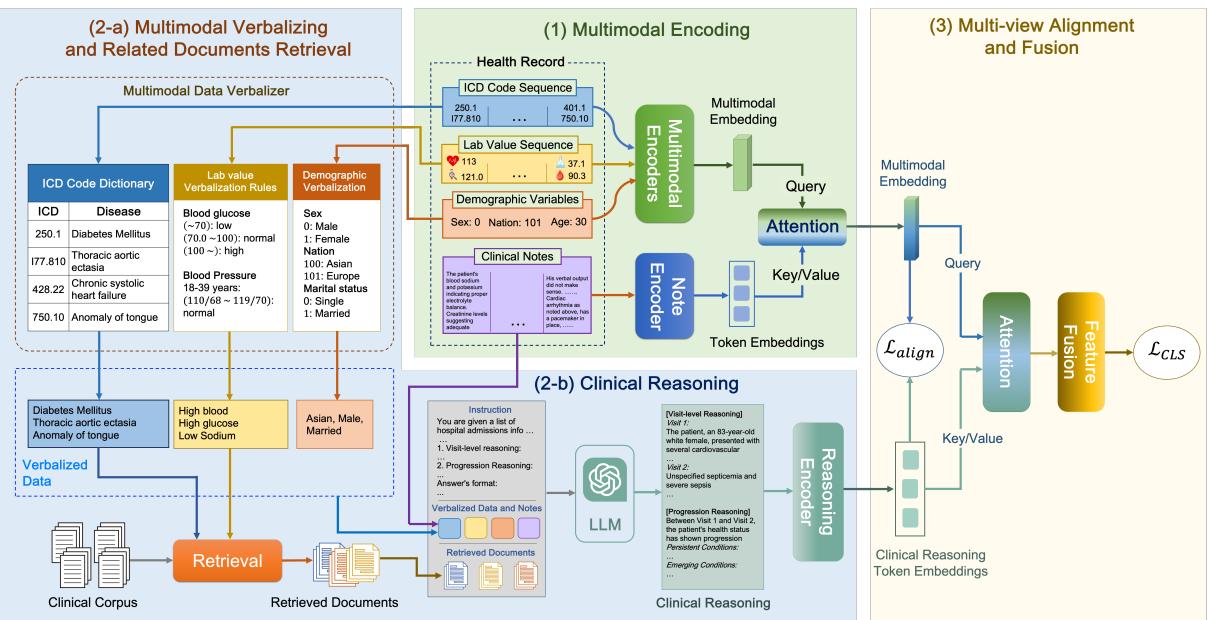

Stage 1: Verbalization and Retrieval (The Context)

LLMs are excellent at text but notoriously bad at interpreting raw numerical matrices or obscure database codes. To get an LLM to reason about a patient, we first need to translate the patient’s data into a language the LLM understands.

Verbalization: The researchers developed a rule-based system to convert structured data into text.

- ICD Codes: Converted to their descriptive names (e.g., code

250.00becomes “Type 2 diabetes mellitus”). - Lab Values: This is critical. A raw number like “115” is meaningless without context. CARER converts this into a semantic string: “High blood glucose, 115 mg/dL.” It categorizes values as low, normal, or high based on medical standards.

- Demographics: “Age: 80, Gender: Male.”

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG): Even capable LLMs hallucinate. To ground the reasoning in medical fact, CARER employs RAG. It uses the verbalized patient data as a query to fetch relevant medical documents from a knowledge base (specifically, PrimeKG).

If a patient has “High blood glucose” and “Hypertension,” the system retrieves documents explaining the relationship between diabetes and blood pressure. This provides the LLM with a “cheat sheet” of verified medical knowledge to support its reasoning.

Stage 2: LLM-Assisted Clinical Reasoning

Now comes the core innovation. CARER uses Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting to guide an LLM (in this study, GPT-3.5) through a structured reasoning process.

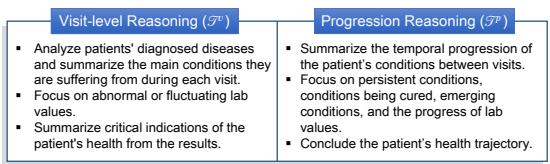

The model isn’t just asked to “predict the risk.” It is instructed to perform two specific types of reasoning, as illustrated in Figure 3:

- Visit-Level Reasoning: Analyze the current admission. What are the diagnoses? Are the lab values abnormal? What does this snapshot say about the patient’s immediate health?

- Progression Reasoning: Look at the changes over time. Which conditions are persistent? Which are new? Is the kidney function deteriorating across visits?

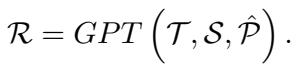

The prompt combines the verbalized data (\(S\)), the specific reasoning instructions (\(T\)), and the retrieved medical documents (\(\hat{P}\)).

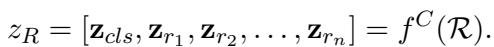

The output, \(\mathcal{R}\), is a comprehensive textual analysis of the patient’s health trajectory. This text is then fed into a Clinical-Longformer encoder—a Transformer model specialized for long clinical texts—to create a dense vector representation of the reasoning, denoted as \(z_R\).

Stage 3: Multi-View Alignment (The Mathematical Glue)

At this point, the network has two distinct representations of the patient:

- \(z_E\) (Multimodal Encoding): A vector derived from standard encoders processing the raw codes, numbers, and original notes. This represents the “Local View”—the specific facts of the patient.

- \(z_R\) (Reasoning Encoding): A vector derived from the LLM’s generated narrative. This represents the “Global View”—the interpretation of those facts through the lens of external medical knowledge.

The Challenge: These two vectors come from different sources and might live in different “semantic spaces.” If we just concatenate them, the model might struggle to relate the raw heart rate number to the LLM’s sentence about “tachycardia.”

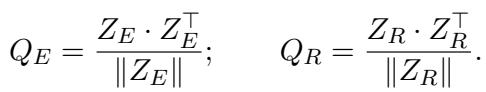

The Solution: Cross-View Alignment Loss. The researchers propose a mechanism to force these two views to be consistent. They calculate similarity matrices for a batch of patients.

- \(Q_E\): How similar is Patient A’s raw data to Patient B’s raw data?

- \(Q_R\): How similar is Patient A’s clinical reasoning to Patient B’s clinical reasoning?

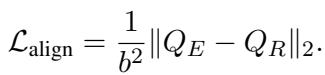

If Patient A and Patient B have similar raw data, their clinical reasoning narratives should also be similar. Therefore, the matrices \(Q_E\) and \(Q_R\) should look the same. The Alignment Loss (\(L_{align}\)) minimizes the difference between these two matrices:

This forces the encoders to learn features that are consistent across both the raw data and the high-level reasoning.

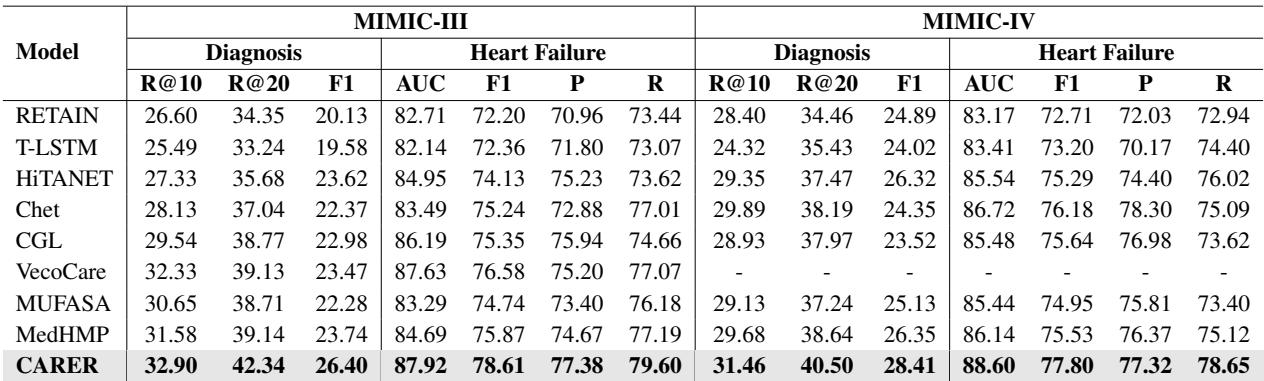

Stage 4: Fusion and Prediction

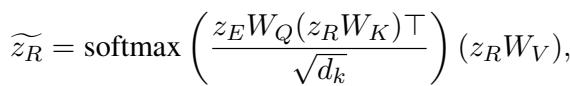

Finally, the model fuses the aligned features. It uses an attention mechanism where the raw data (\(z_E\)) acts as a query to pull the most relevant information from the reasoning vector (\(z_R\)).

These combined features are passed through a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to output the final risk prediction (e.g., probability of Heart Failure).

The total loss function combines the standard classification loss (prediction error) with the alignment loss we defined earlier.

Experiments and Results

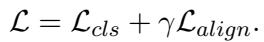

To validate CARER, the researchers tested it on two massive public datasets: MIMIC-III and MIMIC-IV. They focused on two difficult tasks:

- Heart Failure Prediction: Binary classification (will the patient develop heart failure?).

- Full Diagnosis Prediction: Multi-label classification (predicting future disease codes).

Beating the Benchmarks

The results were impressive. CARER was compared against several strong baselines, including RETAIN, HiTANet, and multimodal models like MedHMP and MUFASA.

As shown in Table 2, CARER achieved state-of-the-art performance across the board. In the Full Diagnosis prediction task on MIMIC-III, it outperformed the next best model by over 11% in Recall@10. The gains in Heart Failure prediction were smaller but consistent, achieving an F1 score of nearly 0.80.

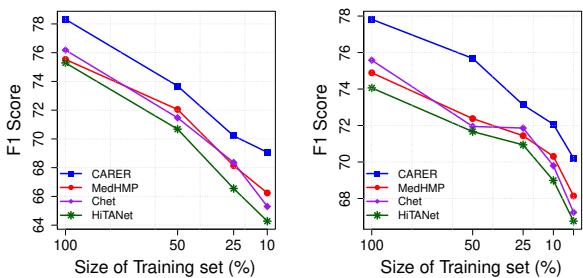

Data Efficiency: Doing More with Less

One of the most significant findings was CARER’s performance in “low-data” regimes. The researchers trained the models using only small fractions (10%, 25%, 50%) of the training data.

Figure 4 (left chart) illustrates this vividly. While the performance of baseline models (like HiTANet and Chet) drops precipitously as data becomes scarce, CARER maintains high performance. Even with only 10% of the training data, CARER achieves an F1 score of nearly 70%.

This suggests that the “clinical reasoning” provided by the LLM acts as a powerful regularizer. It supplements the lack of training examples with general medical knowledge pre-encoded in the LLM.

Does the Reasoning Actually Matter?

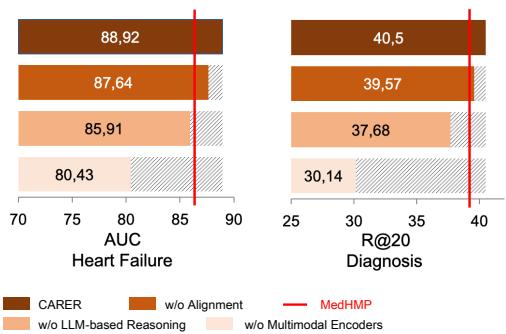

You might wonder: Is the complex architecture necessary? Maybe just adding the LLM text is enough? The researchers performed an Ablation Study to find out.

Figure 6 shows what happens when you remove components:

- w/o Alignment: Removing the mathematical alignment between raw data and reasoning drops performance noticeably. The model needs that “glue” to connect the views.

- w/o LLM-based Reasoning: Removing the reasoning entirely causes a significant drop.

- w/o Multimodal Encoder: Interestingly, relying only on the LLM reasoning (without raw data encoders) performs the worst. This confirms that LLMs are not a replacement for traditional encoders; they are an enhancer. You need both the precision of raw data and the breadth of reasoning.

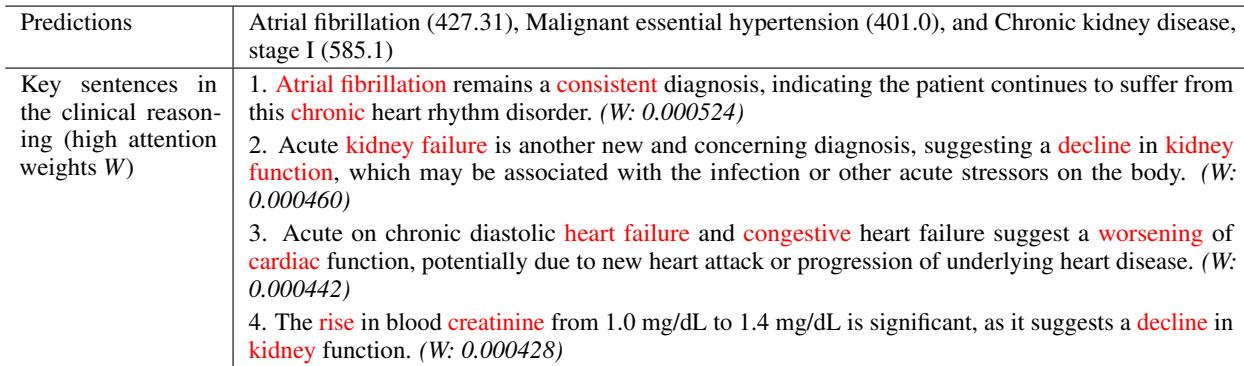

Interpretability: Looking Inside the Reasoning

Finally, one of the biggest advantages of CARER is interpretability. Because the model uses text-based reasoning, we can inspect what the model focused on.

In Table 3, we see a case study where the model correctly predicted Chronic Kidney Disease. By analyzing attention weights, we can see the model focused on sentences discussing “Acute kidney failure” and “rise in blood creatinine.” This transparency allows clinicians to trust the prediction because they can verify the logic behind it.

Conclusion

CARER represents a significant step forward in medical AI. It moves beyond the paradigm of “feeding numbers into a black box” and towards a system that mimics the cognitive processes of a human expert.

By combining Retrieval Augmented Generation, Chain-of-Thought prompting, and a novel Cross-View Alignment mechanism, CARER achieves three major goals:

- Higher Accuracy: It sets new benchmarks for risk prediction.

- Data Efficiency: It works exceptionally well even when patient data is limited.

- Interpretability: It provides understandable rationale alongside its predictions.

For students and researchers in healthcare AI, CARER demonstrates that the future isn’t just about bigger models or more data—it’s about architecture that bridges the gap between statistical learning and semantic reasoning.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2818/images/cover.png)