Beyond Symptoms: How Context and Uncertainty Improve Mental Health AI

Mental health disorders affect over one billion people worldwide. With the rise of social media, platforms have become a space for self-disclosure, offering researchers a massive dataset to help detect conditions like depression or anxiety early.

However, detecting mental disorders from text is notoriously difficult. Early deep learning models were “black boxes”—they could predict a disorder but couldn’t explain why. Recent “symptom-based” approaches improved this by first identifying specific symptoms (like “insomnia” or “fatigue”) and then predicting a disorder. But even these models have a critical flaw: they often ignore context.

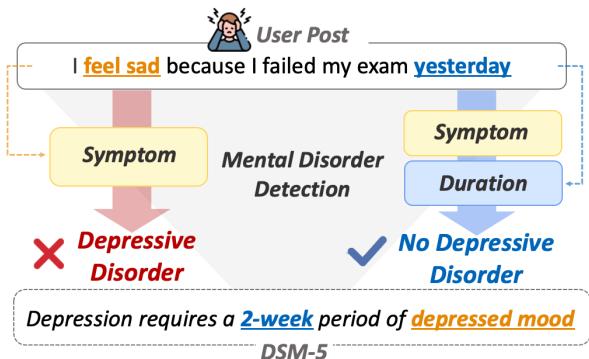

Consider two people saying “I feel sad.” One failed an exam yesterday; the other has felt this way for two months. A standard symptom detector sees “sadness” in both. A psychiatrist, following the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), knows that duration and cause matter.

In this post, we will dive into CURE (Context- and Uncertainty-aware Mental DisoRder DEtection), a novel framework presented by researchers from Sungkyunkwan University and Samsung Medical Center. This paper proposes a method that doesn’t just count symptoms but understands their context and recognizes when the model itself might be uncertain.

The Problem with Symptom-Only Detection

To understand why CURE is necessary, we need to look at the limitations of current interpretable models. Symptom-based models operate in a two-step pipeline:

- Symptom Identification: Scan a post for keywords or phrases indicating symptoms.

- Disorder Detection: Use those symptoms to predict a specific disorder.

The issue is that symptoms are rarely binary. The context—duration, frequency, cause, and impact on daily life—determines the diagnosis.

As shown in Figure 1, a user posting “I feel sad because I failed my exam yesterday” contains a symptom (sadness). A naive model might flag this as depression. However, the context (“yesterday,” caused by an “exam”) suggests a temporary emotional reaction, not a disorder. Conversely, a post mentioning sadness lasting “for a month” aligns with the DSM-5 criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, which requires symptoms to persist for at least two weeks.

Furthermore, these models are prone to uncertainty errors. If the first step (identifying symptoms) is slightly wrong or low-confidence, that error propagates to the final diagnosis.

The KoMOS Dataset

Before building a model, the researchers needed high-quality data. They constructed KoMOS (Korean Mental Health Dataset with Mental Disorder and Symptoms labels). Unlike many datasets scraped from general social media (which are noisy), KoMOS consists of Question-and-Answer pairs from Naver Knowledge iN, where users asked about their mental state and received answers from certified psychiatrists.

This ensured the ground truth labels were medically valid. The dataset covers four major disorders—Depressive, Anxiety, Sleep, and Eating Disorders—along with a “Non-Disease” category, annotated with 28 specific symptoms.

The CURE Framework

The CURE framework is designed to tackle the two main problems identified: the lack of context and the mishandling of uncertainty.

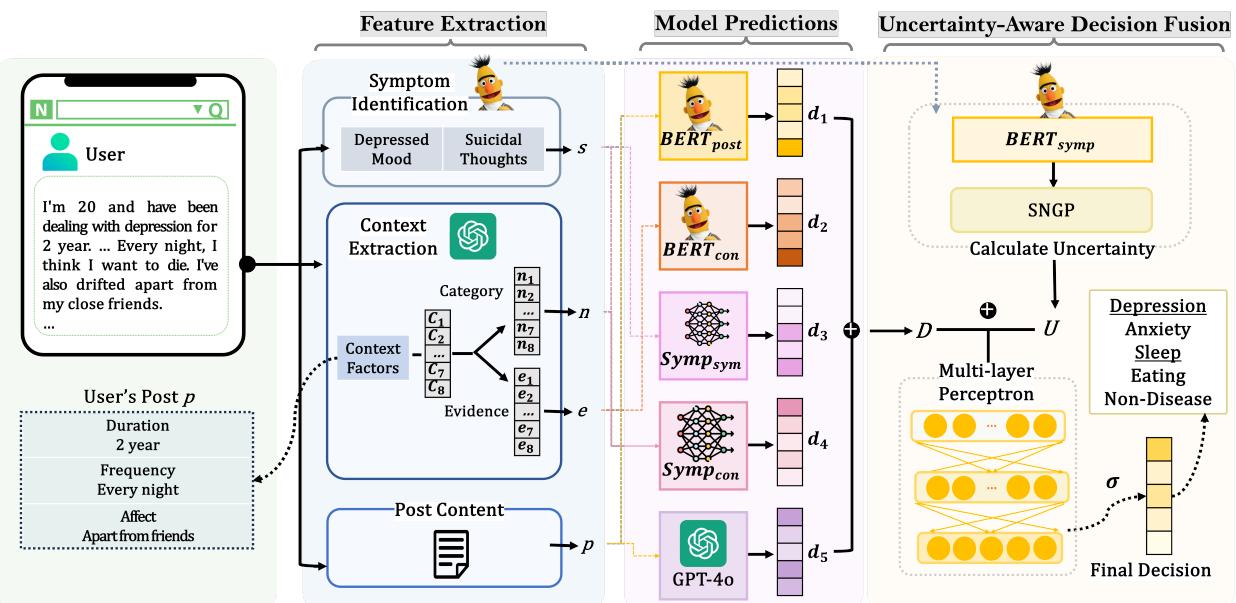

As illustrated in Figure 2, the architecture is divided into three distinct phases:

- Feature Extraction: Mining the text for symptoms and context.

- Model Predictions: Using multiple sub-models to analyze these features.

- Uncertainty-Aware Decision Fusion: Combining predictions while accounting for model confidence.

Let’s break these down step-by-step.

1. Feature Extraction

The model extracts two types of information from a user’s post.

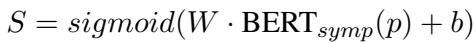

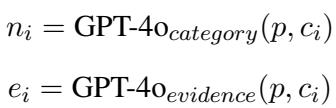

Symptom Identification First, the system needs to find clinical symptoms. The researchers used a fine-tuned BERT model. For a given post \(p\), the model calculates a likelihood vector \(S\) for 28 different symptoms (e.g., “Depressed mood,” “Insomnia,” “Suicidal thoughts”).

This equation essentially runs the BERT representation of the post through a classifier to get the probability of each symptom being present.

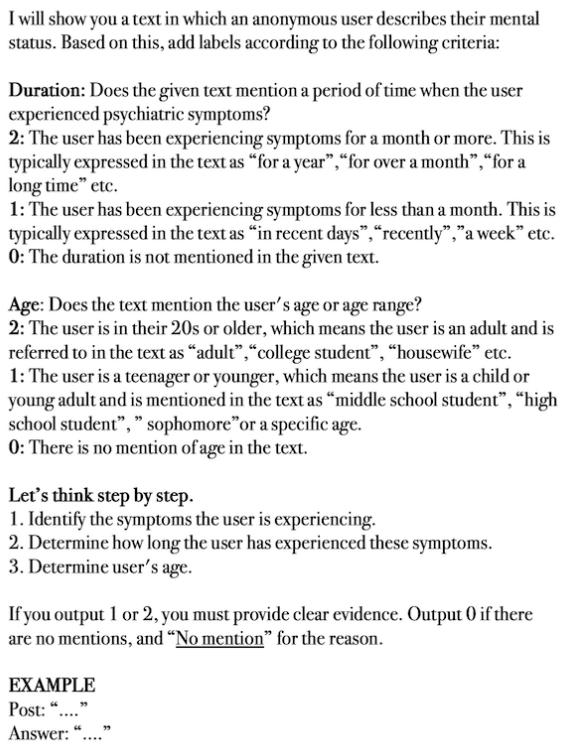

Context Extraction via LLMs This is where CURE innovates. Instead of relying on simple keyword matching for context, the researchers utilized a Large Language Model (specifically GPT-4o) to extract eight specific contextual factors defined by psychiatrists:

- Cause: Is there a specific trigger?

- Duration: How long has this been happening?

- Frequency: How often does it occur?

- Age: How old is the user?

- Affects (4 types): Does it impact Social, Academic, Occupational, or Life-threatening aspects?

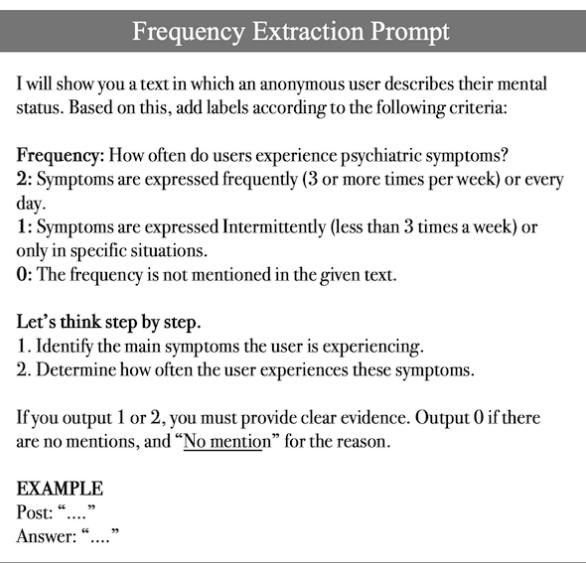

The researchers designed specific prompts using “Chain-of-Thought” reasoning to guide the LLM.

As seen in the prompts above, the LLM is asked to categorize the text (e.g., Duration: 0 for no mention, 1 for <1 month, 2 for >1 month). This transforms unstructured text into structured “Context Categorical” vectors (\(N\)) and “Context Evidence” vectors (\(E\)).

2. Model Predictions (The Ensemble Approach)

Simply concatenating symptom vectors and context vectors into one model can be inefficient because the features are so different in nature. Instead, CURE employs an ensemble of five sub-models, each looking at the data from a different angle:

- BERT-post: Looks at the raw text of the post.

- BERT-context: Uses the context evidence extracted by the LLM.

- Symp-symptom: Uses only the symptom likelihood vector.

- Symp-context: Concatenates the symptom vector and the context categorical vector.

- GPT-4o: A direct prediction from the LLM itself.

This diversity ensures that if one method fails (e.g., the symptom extractor misses a keyword), another (e.g., the raw text analyzer) might catch it.

3. Uncertainty-Aware Decision Fusion

This is the final and perhaps most technical piece of the puzzle. Traditional deep learning models are often “overconfident”—they might predict a high probability for a class even when the input data is confusing or unlike anything they’ve seen before (out-of-distribution).

To fix this, the researchers used Spectral-normalized Neural Gaussian Process (SNGP). Without getting too bogged down in the math, SNGP is a technique that allows a neural network to estimate how uncertain it is about a prediction.

The framework calculates an uncertainty value (\(U\)) specifically for the symptom identification model. It then fuses this uncertainty with the predictions (\(D\)) from all five sub-models using a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP).

Here, \(H\) is the hidden representation that combines the predictions \(D\) and the uncertainty \(U\). The final output \(\hat{y}\) is the actual diagnosis.

Why does this matter? If the symptom model is unsure (high \(U\)), the fusion network learns to trust that model less and perhaps rely more on the context-based sub-models.

Experimental Results

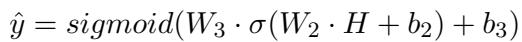

The researchers compared CURE against several baselines, including standard BERT models, other symptom-based models (like PsyEx), and raw LLMs (GPT-4o, MentalLLaMA).

Performance Comparison

The results on the KoMOS dataset were impressive. The table below highlights the Recall and F1 scores.

Key Takeaways:

- Best Overall Performance: CURE achieved the highest F1 scores across almost all categories.

- The Non-Disease Challenge: Look at the “Non-Disease” column. Most models struggle here because they tend to over-diagnose. CURE significantly outperforms others (F1 of 0.649 vs 0.626 for the next best), proving that context helps the model realize when not to diagnose a disorder.

- LLMs alone aren’t enough: Interestingly, while GPT-4o is powerful, using it directly for diagnosis resulted in high recall but lower precision (over-diagnosis). CURE uses the LLM for feature extraction (context) rather than the final decision, which proved more effective.

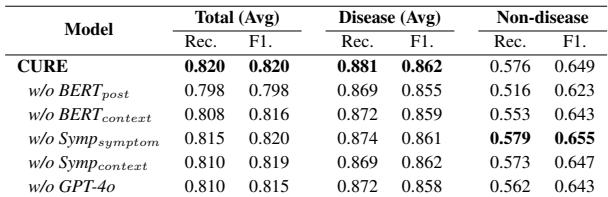

The Impact of Sub-Models

Does using five different models actually help? The researchers performed an ablation study, removing one model at a time to see what happened.

As shown in Table 4, removing any single sub-model resulted in a performance drop. Notably, removing BERT_post or BERT_context hurt the “Non-disease” detection the most. This confirms that the raw text and context evidence are crucial for filtering out false positives.

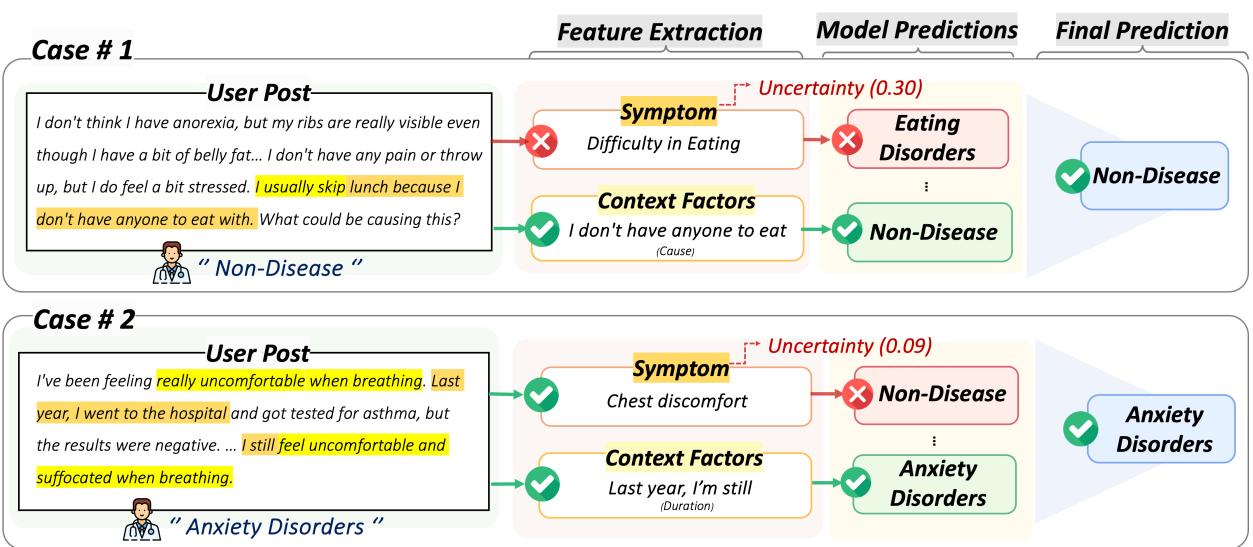

Case Study: Seeing CURE in Action

To make this concrete, let’s look at two real-world examples from the study where CURE succeeded while other models failed.

Case #1 (Left):

- User Post: “I don’t think I have anorexia… usually skip lunch because I don’t have anyone to eat with.”

- The Error: A standard symptom model sees “skip lunch” and flags “Difficulty in Eating,” predicting Eating Disorder.

- The CURE Solution: The context extraction notes the social cause (“don’t have anyone to eat with”). The uncertainty-aware fusion weighs the conflicting evidence and correctly predicts Non-Disease.

Case #2 (Right):

- User Post: “I’ve been feeling really uncomfortable when breathing… since last year.”

- The Error: A symptom model sees “Chest discomfort” but misses the broader picture, predicting Non-Disease (perhaps thinking it’s a physical issue).

- The CURE Solution: The context extraction highlights the Duration (“since last year”). This chronic nature, combined with the symptom, aligns with Anxiety Disorders, leading to a correct diagnosis.

Conclusion

The CURE framework represents a significant step forward in automated mental health analysis. By moving beyond simple keyword spotting and integrating contextual understanding (via LLMs) and uncertainty quantification (via SNGP), the model aligns much closer to how a human psychiatrist operates.

The key contributions of this work are:

- Context Matters: Distinguishing between temporary distress and chronic disorders requires understanding duration, frequency, and cause.

- Uncertainty is Useful: Knowing when a model is unsure allows for better decision-making than blind confidence.

- KoMOS: A valuable, expert-annotated resource for the Korean mental health research community.

While currently focused on Korean text and four specific disorders, the methodology behind CURE—specifically the hybrid use of LLMs for context extraction and uncertainty-aware fusion—is a blueprint that can be applied to mental health detection in any language.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2827/images/cover.png)