Introduction: The Confidently Wrong Machine

Imagine asking an AI assistant for medical advice or a legal precedent. It gives you an answer immediately, with perfect grammar and an authoritative tone. But there is a problem: the answer is completely made up.

This phenomenon, often called “hallucination,” is one of the biggest hurdles in deploying Large Language Models (LLMs) like LLaMA or GPT-4 in critical real-world applications. The core issue isn’t just that models make mistakes—humans do that too. The issue is that LLMs often lack the ability to know when they are making a mistake. They are frequently “confidently wrong.”

For humans, expressing uncertainty is natural. If you aren’t sure about an answer, you might say, “I think it’s Paris, but I’m only about 60% sure.” Standard LLMs, however, struggle to verbalize this internal probability accurately.

In a fascinating research paper titled “Can LLMs Learn Uncertainty on Their Own?”, researchers from the University of Macau and Harbin Institute of Technology propose a novel method to fix this. They argue that we can teach LLMs to align their verbalized confidence with their actual probability of correctness. The result? A model that knows when it doesn’t know, enabling it to call for help—like searching the web—only when necessary.

In this post, we will break down their methodology, the Uncertainty-aware Instruction Tuning (UaIT), and explore how they achieved a massive 45.2% improvement in uncertainty expression.

The Challenge of Measuring Uncertainty

Before diving into the solution, we need to understand why this is hard. Historically, measuring how “unsure” a neural network is has been done in two ways:

- Verbalized Confidence: Simply prompting the model, “Are you sure? Give me a score from 0 to 100.” Research shows LLMs are generally poor at this; they tend to be overconfident sycophants.

- Sampling-Based Estimation: You ask the model the same question 10 times. If it gives 10 different answers, it’s uncertain. If it gives the same answer 10 times, it’s confident. While accurate, this is computationally expensive and too slow for real-time chat applications.

The researchers sought a “best of both worlds” approach: a model that can express accurate confidence in real-time (like method 1) but with the reliability of mathematical estimation (like method 2).

The Solution: Uncertainty-aware Instruction Tuning (UaIT)

The core idea of the paper is Self-Training. The researchers realized they could use the slow, accurate methods (sampling) to generate a training dataset, and then use that dataset to teach the model to express uncertainty instantly.

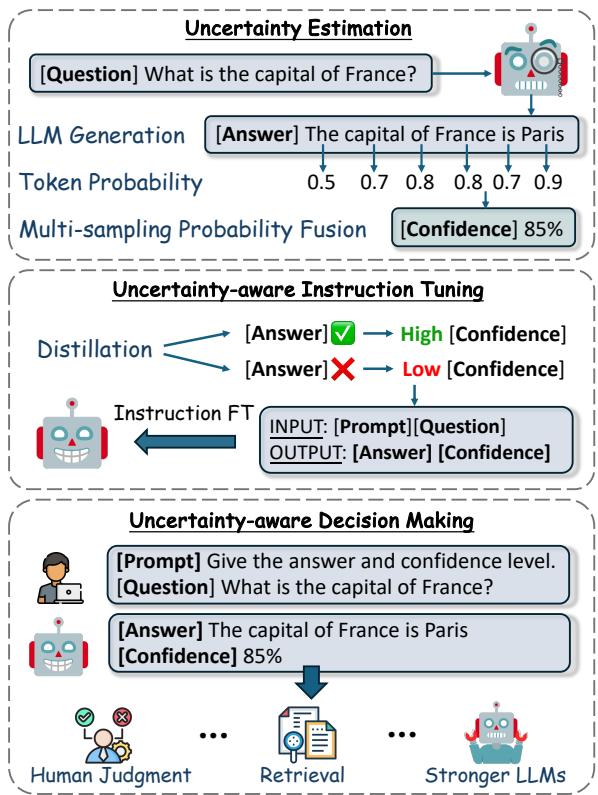

As illustrated in Figure 1 below, the process is a pipeline consisting of three stages: Uncertainty Estimation, Instruction Tuning, and Decision Making.

Let’s break these stages down in detail.

Stage 1: The “Teacher” (Uncertainty Estimation)

To train a model to be humble, we first need a “ground truth” for uncertainty. The researchers utilized a method called SAR (Shifting Attention to Relevance).

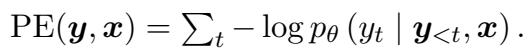

Standard uncertainty measurement usually looks at Predictive Entropy (PE). This is a fancy way of calculating how “spread out” the model’s probability distribution is for the next word.

However, SAR argues that not all words are created equal. If a model is uncertain about the word “The” at the start of a sentence, it doesn’t matter much. If it is uncertain about the specific entity “Paris,” that matters a lot.

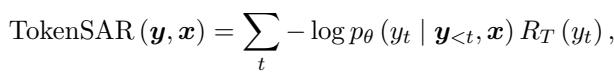

SAR improves upon standard entropy by calculating a relevance weight (\(R_T\)) for each token. It does this by removing a token from the sentence and seeing how much the meaning changes. If the meaning changes drastically, the token has high relevance.

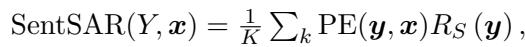

The equation for Token-level SAR combines the probability of the token with its semantic relevance:

Here, \(R_T\) represents the relevance weight. The researchers calculate this relevance by comparing the semantic similarity of the sentence with and without the token, as defined mathematically here:

Furthermore, they extend this to the sentence level using Sentence-level SAR. By sampling multiple answers (let’s say 5 different variations) and comparing them, the algorithm assigns higher confidence to sentences that are semantically similar to the majority of other generated answers.

Where sentence relevance (\(R_S\)) is calculated by summing the similarities between the current sentence and other sampled sentences:

By combining these, the researchers obtain a highly accurate, albeit slow, “Confidence Score” for any answer the LLM generates. This score serves as the label for the training phase.

Stage 2: The Curriculum (Data Distillation)

Now that we have a way to score confidence (the “Teacher”), we need to create a textbook for the “Student” (the LLM itself).

The researchers took a dataset (TriviaQA) and had the LLM answer the questions. They then calculated the SAR confidence score for every answer. But simply feeding this back to the model isn’t enough. They applied a Distillation strategy.

They filtered the data to keep only the most instructive examples:

- High Consistency Correct: Cases where the model was correct and the calculated confidence was high (above a certain threshold, e.g., 80%).

- High Consistency Incorrect: Cases where the model was wrong and the calculated confidence was low (below a threshold).

This filtering removes “confusing” data points where the model might have guessed correctly by accident (low confidence but correct) or was confidently wrong (hallucinating). This creates a clean signal for the model to learn: “This is what certainty feels like” and “This is what uncertainty feels like.”

Stage 3: The “Student” (Instruction Tuning)

Finally, the researchers fine-tune the LLM. The input is the user’s question, and the target output is the Answer + The Confidence Score.

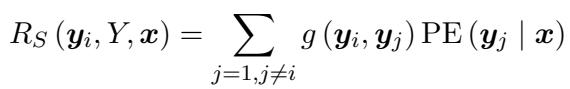

The optimization goal is to minimize the difference between the model’s predicted output and this curated dataset.

By training on its own past behaviors (labeled with accurate math), the LLM internalizes the concept of uncertainty. It learns to associate specific internal states—patterns of neuronal activation that occur when it lacks knowledge—with the output of a low percentage score.

Experiments and Results

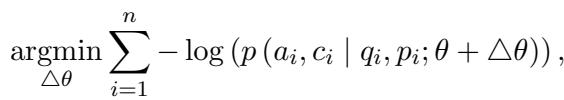

Does this actually work? The researchers tested this method using LLaMA-2 and Mistral models on three datasets: TriviaQA (general knowledge), SciQA (science), and MedQA (medicine).

They used AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic) as their primary metric. In plain English: if you take a correct answer and an incorrect answer, AUROC measures the probability that the model assigns a higher confidence score to the correct one.

- 0.5 = Random guessing.

- 1.0 = Perfect calibration (always higher confidence for correct answers).

Massive Improvements in Calibration

The results, shown in the table below, were striking.

Key Takeaways from the Data:

- Verbalized Confidence fails: Asking the vanilla model “Are you sure?” (the “Verbalized” row) results in AUROC scores near 0.5 or 0.6. The models are barely better than random at self-evaluation.

- UaIT dominates: The proposed method (UaIT) achieved AUROC scores of 0.846 and 0.867 on TriviaQA. This is a massive improvement over the baseline.

- Beating the Teacher: Surprisingly, UaIT often performed better than SAR (the method used to generate the training labels). By generalizing from the training data, the model learned a more robust representation of uncertainty than the raw mathematical approximation provided.

The Role of Distillation

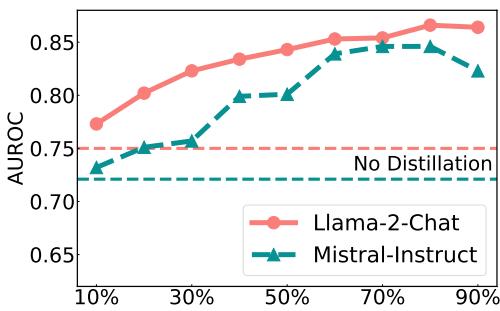

How important was that filtering step in Stage 2? The researchers analyzed how different thresholds for data distillation impacted performance.

As Figure 2 shows, performance generally improves as the distillation becomes stricter (moving to the right on the x-axis). Using a threshold around 85% yielded the best results. This confirms that training on “clean” signals (where accuracy aligns with confidence) is crucial for the model to learn effectively.

Generalization Capabilities

A major concern in machine learning is overfitting. If we train the model on TriviaQA, will it only know how to estimate uncertainty for trivia?

Looking back at Table 1, we see the columns for SciQA and MedQA. Even though the model was only fine-tuned on TriviaQA, it maintained strong performance on Science and Medical questions. This suggests that UaIT teaches the model a generalizable skill: the ability to introspect its own knowledge, regardless of the topic.

Real-World Application: Uncertainty-Aware Decision Making

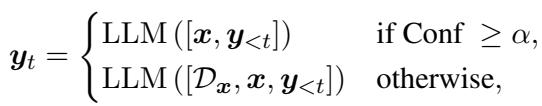

Why do we care about a confidence score? Because it allows us to build smarter AI systems. The researchers proposed a decision-making framework where the AI acts differently based on its confidence.

The logic is formalized as follows:

Simply put:

- If Confidence \(\ge\) Threshold: Output the answer immediately.

- If Confidence < Threshold: Retrieve external documents (RAG) or ask a stronger (larger) model for help.

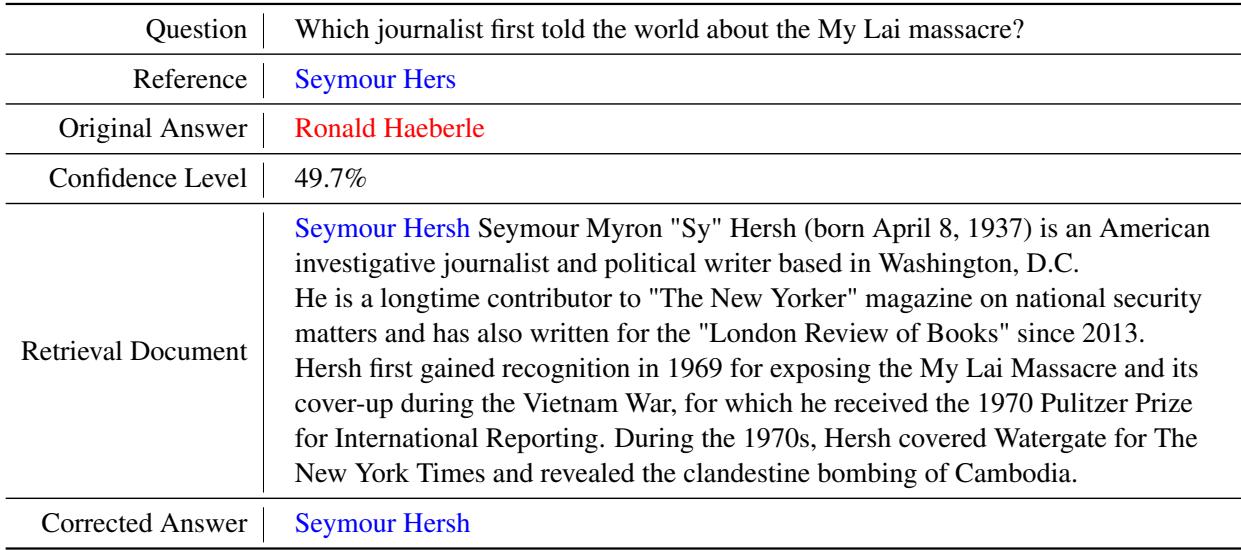

Case Study: Correcting Hallucinations

The researchers provided a concrete example of this in action.

In Table 5, the model initially thinks “Ronald Haeberle” revealed the My Lai massacre. However, UaIT flags this with a low confidence score of 49.7%. This low score triggers a retrieval step. The model reads an external document about Seymour Hersh, realizes its mistake, and corrects the answer to “Seymour Hersh.”

Without UaIT, the model would have just confidently stated the wrong name.

Quantitative Success in Decision Making

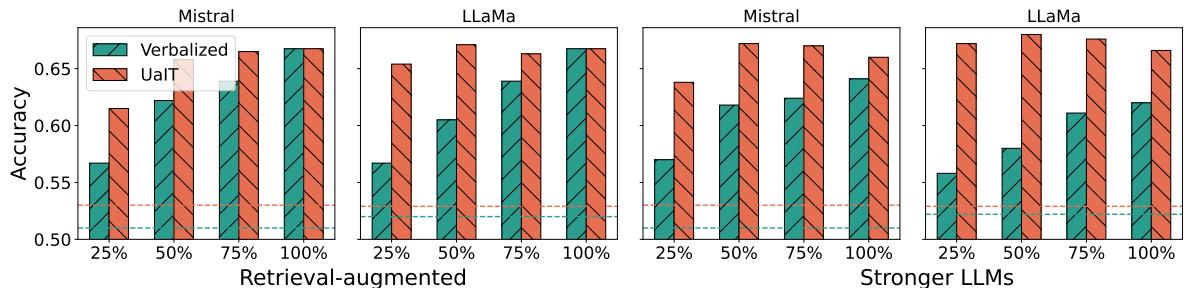

This isn’t just an isolated example. The researchers tested this strategy systematically. They set up a system where the bottom 25%, 50%, or 75% of confident answers would trigger a retrieval step.

Figure 3 illustrates the results:

- The Teal Bars (Verbalized): Relying on the model’s standard confidence is inconsistent.

- The Orange/Red Bars (UaIT): Using the trained confidence consistently leads to higher accuracy.

Notably, by retrieving information only when UaIT indicates low confidence (the “25%” mark), the system achieves significant accuracy gains without the computational cost of retrieving documents for every query.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Can LLMs Learn Uncertainty on Their Own?” presents a compelling step forward for reliable AI. By using a “Teacher” algorithm (SAR) to label data and a “Student” process (Instruction Tuning) to internalize it, LLMs can be taught to recognize their own limitations.

The implications are significant:

- Efficiency: We can get high-quality uncertainty estimates in real-time without expensive multi-sampling.

- Reliability: Systems can automatically “phone a friend” (browse the web) when they are confused, reducing hallucinations.

- Self-Awareness: We are moving closer to models that possess a functional form of metacognition—knowing what they know and what they don’t.

For developers and students of AI, this highlights that calibration is just as important as accuracy. A model that knows it is wrong is infinitely more useful than a model that thinks it is always right.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/file-2835/images/cover.png)